Artwork selection from Human Impact Stories: The Climate Crossroads exhibit curated by GiGi Buddie ’23.

Left to right, top to bottom: Severiana Domínguez González (Mexico) illustrated by Sino Ngwane (South Africa); Saraswati Dhruv (India) illustrated by Radja Ouslimane (Algeria); Gabriella Sakina (DRC) illustrated by Maryam Lethome (Kenya); Raquel Cunampio (Panama) illustrated by Astrid “Lotus” Caballeros (Guatemala).

See complete series at humanimpactsinstitute.org/climatecrossroads

On the other side of the Atlantic last November, Pomona College student GiGi Buddie ’23 stood behind a dais marked with the familiar United Nations logo and the words “UN Climate Change Conference UK 2021.” She was in Glasgow as a youth delegate to COP26 representing Human Impacts Institute, a nonprofit that uses art and culture to inspire environmental action.

The stage, and the microphone, were hers.

“I am Mescalero Apache and Tongva Indian,” Buddie began as she spoke at a joint event with the Bolivian delegation inside the Blue Zone, the vast area managed by the United Nations where negotiations and other events took place.

“I am a daughter, sister, student, artist, warrior and caretaker of this earth,” Buddie continued, the beaded earrings crafted for her by Chickasaw student Coco Percival ’21 dangling from her ears. “I am standing here before you on behalf of my ancestors who fought to give me life, give me a voice, give me a home and a community to remind me of my roots that extend deep into this earth. For it is because of my ancestors that I am here. It is because of them that I can see light in a world that seems to grow darker each passing year. They give me hope. They give me strength. It is because of them that I fight so hard here, though we must all confront the truth that this shouldn’t be a fight.

“There is no debate on human lives and history. There is no debate on the hurt and grief and the immense loss that my people have suffered. There is no debate on what’s right and wrong because colonial and capitalist morals are rooted in greed and corruption. There is no debate. There can only be what do we do now? How do we move forward more knowledgeably? How can we share the seats at a table with voices that know this earth?”

Buddie grew up as what is sometimes called an urban Indian, living with her family outside San Francisco. What she learned about her heritage came mainly from stories and rituals introduced by her mother, Kaia, and from visits to the annual Stanford Powwow, one of the largest such gatherings on the West Coast. At Pomona, Buddie’s understanding of the experiences of other native peoples has deepened with her involvement in the Indigenous Peer Mentoring Program on campus and lessons learned from local Tongva elders such as Barbara Drake and Julia Bogany before their recent passings.

Growing up in the Bay Area, GiGi Buddie often attended the Stanford Powwow (shown here), the largest student-organized powwow in the nation.

It is as a theatre major and environmental analysis student at Pomona that Buddie has found the place where her heritage melds with her talents and the urgent need for action in the face of climate change. She has become an environmental warrior whose chosen weapon is art, whether it is the spoken word, a poem, visual art or a performance onstage.

The work that took her to COP26 with Human Impacts Institute was the multimedia exhibit she curated as an intern, Human Impact Stories: The Climate Crossroads, highlighting 10 Indigenous women and youth from around the world who are environmental activists.

On display at Glasgow’s Centre for Contemporary Arts and later inside the COP26 Blue Zone, the exhibit featured oversized prints of the activists’ portraits—each created by an Indigenous or Afro-descendant artist—along with the stories of their work and the ways of life they seek to protect.

Brazil’s Watatakalu Yawalapiti, founder of the Xingu Women’s Movement, works to increase Indigenous women’s political voices in battling such issues as deforestation in the Amazon region. Indonesian teenager Kynan Tegar fights with a camera, using film and storytelling to show the effects of environmental changes on his Dayak Iban people of Borneo. Vehia Wheeler, cofounder of Sustainable Oceania Solutions Mo’orea, is an academic, consultant and activist working to teach youth in Oceania to combine ancestral knowledge with STEM methods to protect the environment.

Buddie collaborated with Tara DePorte, the founder and executive director of Human Impacts Institute, to select the featured activists from nominations from around the world, focusing on the Southern Hemisphere. Buddie then identified Indigenous artists to commission for the striking, colorful portraits that drew people into the exhibit. She also interviewed the featured leaders—sometimes requiring a translator—and wrote brief biographies to accompany transcripts of the interviews, all of which are available at the Human Impacts Institute website.

The point was to amplify their work and their voices, so that others trying to find solutions to climate change recognize that many Indigenous people already are experiencing effects from environmental change—and that the wisdom of their elders provides ideas to combat it that aren’t being heard.

“Indigenous communities usually have very close ties to nature, living with the land rather than on the land, taking advantage of what is there and always giving back,” Buddie says, noting that such practices as using controlled burns to prevent wildfires have been practiced by native peoples for thousands of years. “The sad part is that the climate crisis most often affects Indigenous communities and minority communities in greater ways than it does in more wealthy communities. They’re the first impacted and hardest hit.”

During her time in Scotland, Buddie experienced both exhilaration and frustration.

“Everything was so new and overwhelming, mostly in a good way,” she says. “When we got the exhibit all set up and the video was playing, the music was on and people started to trickle in, I just realized: It’s real; we’re here. All the work that we’ve done, it’s here at COP26.”

Listening to those who visited gave

her a sense of meaning.

“I got a lot of, ‘This was eye-opening. I didn’t know this,’” she says.

Her varied work in the Indigenous climate movement has expanded during her time at Pomona. As a first-year student, she took an acting course with Prof. Giovanni Ortega that introduced her to This Is a River, a play being written by Pomona Theatre Prof. James Taylor and Isabelle Rogers ’20. That summer, Buddie joined them on a research expedition to Borneo, the play’s setting, where she was stunned to see how deforestation, palm oil plantations and the building of dams affected the Indigenous people who make their homes along the Baram River.

Her efforts to convey the urgency of climate change through art have included work with the nonprofit The Arctic Cycle and its Climate Change Theatre Action project, a worldwide series of performances of short climate change plays that Buddie has been part of on Pomona’s campus. Last fall, she acted as producer for the Pomona event and brought in speaker Chantal Bilodeau, the Arctic Cycle’s founding artistic director, now one of Buddie’s mentors.

A play, Buddie has come to believe, is a perfect way to reach people.

“You quite literally have a stage,” she says. “I think what’s so beautiful about theatre and other forms of art, visual and performing, is that anything that has to do with scientific jargon or academia can be so scary,” she says. “However, when you take the science of it and put the issue into a play, you’re making it more accessible and you’re creating an environment where people can absorb and interact with this material in a way that they’re able to connect with and understand. It’s also a way to tug at the heartstrings a little bit. When you see the IPCC [Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change] Report, it’s scary. But taking it and putting it into art creates an avenue where anybody can come to it, and it can be accessible. That’s really powerful.”

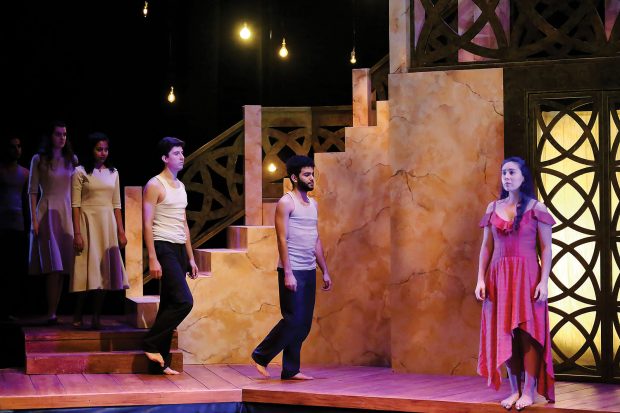

Ortega, the theatre professor who traveled with the Borneo research group, praises Buddie’s acting in roles in campus productions including 2019’s Metamorphoses and Circle Mirror Transformation last fall.

GiGi Buddie, right, performs in Metamorphoses in 2019

Photo by Ian Poveda ’21

“Not only is she very keen on these issues, she’s also a phenomenal actress,” Ortega says. “But I think what’s really important about her is the amount of empathy that she carries, as a person who identifies as Indigenous and someone who cares about the environment. She’s more passionate than ever, and that was really evident when she came back from COP26. You could tell that this is a fire that’s inside of her, because this generation is just really exhausted with the pace that we are going regarding environmental change.”

Inside the Blue Zone in Glasgow, Buddie caught glimpses of activists such as Al Gore and Leonardo DiCaprio. Yet at the same time, she felt a simmering resentment toward world leaders and corporations she feels aren’t acting quickly enough to address climate change.

“It was so painful and eye-opening to sit there knowing that these world leaders were not truly listening, or if they were listening, it was some scheme to make themselves look better by saying, ‘We’re listening,’” she says. “They’re saying that they’re throwing coins in a wishing well for how we want the planet to change. I’m thinking, ‘You have the power. You are the power that makes the change. Do it.’”

It was, after all, COP26, meaning that the Conference of the Parties, the decision-making body responsible for the implementation of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate, had met 25 times before, since 1995. António Guterres, the U.N. Secretary General, opened COP26 by saying the top priority must be to limit the rise in global temperatures since pre-industrial times to just 1.5 degrees Celsius. Already, the world has warmed 1.1 degrees.

British Prime Minister Boris Johnson and U.S. President Joe Biden were accused of nodding off because of photos such as this.

“I think that especially at this climate summit, it was just so real and in your face that we don’t have time,” Buddie says. “Like Joe Biden and Boris Johnson falling asleep in the middle of negotiations. The entire world is watching you. The entire world is listening. And that’s what you do?”

What she wants most desperately and is trying to encourage through art is for people to listen, and to act.

“Which, seeing it at COP, everywhere you looked, it was just people pretending to listen.”