Photo by Michael Chess: White Sands, New Mexico

Photo by E. Pia Struzzieri

Tom Lin ’18 is too old to be a child prodigy.

But he’s young enough that the attention and praise he has received for his first novel, The Thousand Crimes of Ming Tsu, is extraordinary. To garner the critical acclaim it has—and to be selected a New York Times Book Review Editors’ Choice and win the 2022 Andrew Carnegie Medal for Excellence in Fiction—is certainly not typical for a writer who only recently turned 26.

Sometimes compared to Cormac McCarthy’s work, Lin’s novel is a classic Western that features a Chinese American assassin as its protagonist. Lin started his book as a student at Pomona College, guided by professor and novelist Jonathan Lethem and advised by the late Professor Arden Reed. Lin says with all the accolades, he keeps “expecting to wake up” from what seems like a dream.

Now a Ph.D. student at UC Davis, Lin is working on a science fiction project while continuing his graduate work.

But every story, written or lived, has its beginning.

Lin grew up in New York and got his first car while at Pomona. Unsupervised at the wheel, he crisscrossed the Southern California landscape, most notably the Mojave Desert and Joshua Tree National Park. Lin had never seen anything like those places in his life. (Actually, he was corrected in a family text thread: He traveled to the West Coast when he 4. But college was the first time he was sentient in the Wild West, he says.)

Inspired by the scenery, Lin thought he should write a Western as a tribute. But it was a tribute with a twist. The main character would be Chinese American. For Lin, this wasn’t just a matter of preference; this was a matter of urgency, never mind history. The California public schools curriculum includes the history of Chinese laborers on the Transcontinental Railroad, but Lin’s East Coast curriculum had not.

“I was learning this new history, getting more involved in it, and it more and more would seem like a story that I had to tell,” he says. “I had to do it right as well.”

Doing it right was a challenge. Lin knew very little about traditional Westerns. What he did know were books by authors such as Cormac McCarthy, who subverted the genre.

“I think I got to know Westerns through this kind of meta-Western universe, which is interesting—to read around a thing but never actually encounter the thing,” Lin says.

He didn’t let that hinder him.

“The Western as a genre has a set of affordances and is so deeply ingrained in American culture,” he says. “It’s hard to get away from the skeletons of the Western even in stuff that wouldn’t appear to be Westerns, because we just love them so much as a country. And so paradoxically I felt quite well prepared to write a Western. I never felt that anything was lacking because I hadn’t read Westerns, because I felt as though I had been reading Westerns all my life in these other forms.”

Lin’s novel had humble beginnings; it started as homework. His work was a submission for a creative writing workshop with Lethem, the much-celebrated novelist and Pomona College’s Roy Edward Disney ’51 Professor of Creative Writing and Professor of English.

Lin’s novel had humble beginnings; it started as homework. His work was a submission for a creative writing workshop with Lethem, the much-celebrated novelist and Pomona College’s Roy Edward Disney ’51 Professor of Creative Writing and Professor of English.

“My peers were very kind to me, because I turned in something that was way beyond the length cutoff for what you would give for a workshop,” Lin says. “It had a main character named Ming Tsu and it was a Western, but it was set in the present day. My thinking was that this was just a chapter, and I would go and work on it more. But at the end of it, Ming Tsu, he gets in his car and he says, ‘I’m going to drive across the country,’ because I was about to do that at the end of that year, just to go home. And I remember someone in the class during feedback they said, ‘Oh, it won’t take that long to drive across the country. I’ve done it in two days.’ And I almost out of spite put [Ming Tsu] on a horse to see how long it takes for him to get anywhere.”

Lin worked intermittently on the manuscript throughout his time at Pomona. He loved that his professors treated him as a peer. But he admits he didn’t complete the novel in college because he was “having too much fun. And of course, as soon as I graduated, that ceased to be a problem almost instantly.”

So Lin finished the book in the year that he took between college and grad school. Following that were a host of revisions and a return to his mentor Lethem. Although Lin had only taken the beginning fiction workshop with the professor, not the advanced workshop, Lethem offered an open door and critical eye for the young graduate’s manuscript. While Lin was prepared for feedback, he wasn’t prepared for Lethem’s “incredibly generous blurb,” he says.

“I was bowled over. That was something that I could then take when we were showing the manuscript to editors. That helped immeasurably. I don’t think any of this would have been possible without his generosity.”

Writing is often difficult for him, Lin says. Some of his productive days produce a grand total of 250 words. But because writing is so hard, he does a lot of research.

“That is much more satisfying and also there’s less hair-pulling and heartache involved,” he says. “I tend to think and imagine and ultimately write in short scenes, just bursts of description or action, and I produce what I consider to be fragments. And then when I want to start stitching the whole thing together, it becomes a process of bricks and mortar, rather than weaving out of whole cloth. But my writing process I think in a word is ‘slow.’”

Lin remembers that he would Google “famous writer, process,” to see if he was doing something wrong.

“There are these writers who wake up at 5 a.m. and they go for a run, and they take the kids to school, and then they write for eight hours and … I don’t know how you do that day after day.”

As an English major, Lin was trained in looking for sources first and then building an analysis.

“I think when it comes to writing fiction, it’s almost the exact same process except that at the end what I built isn’t an interpretation, but actually something that seems to attend to all of those issues that came up during research.”

Lin claims he is “slow.” That said, his first novel was published a mere three years out of college. But what seems like a rapid turnaround was actually a long-desired realization. He had always been writing in some form or fashion but wasn’t so sure he could make a living with words. It was akin to the “When I grow up, I want to be an astronaut” dream, he says. But he had been hyping this project to his friends, so it was finally self-imposed social pressure that brought him to the finish line.

“As for Tom Lin, I would simply say that if he hadn’t been one of my most attentive and fluent and compassionate workshop students I’d probably claim now that he had been, simply to associate myself with the marvelous achievement of his first novel and all the next gifts he promises to eager readers, such as myself. But he was!”

Jonathan Lethem

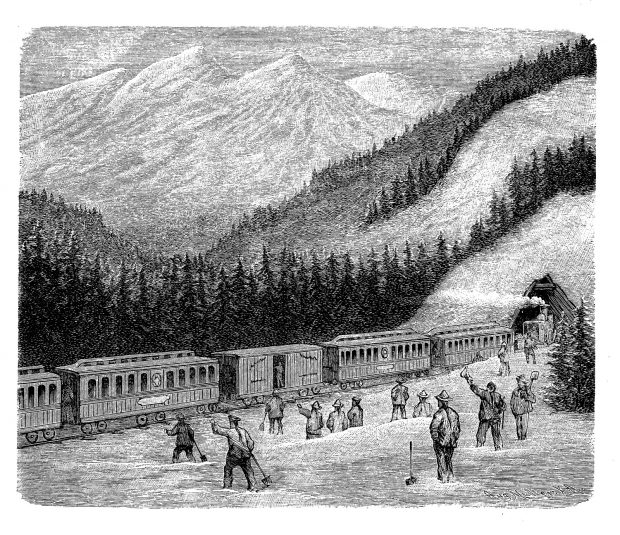

Of course, writing isn’t really a race; it is a craft. While Lin typed, he kept history at the forefront of his mind as well as the concept of invisibility that Ralph Ellison brilliantly illuminated in Invisible Man. Chinese immigrants essentially built the Central Pacific Railroad line, but they faced both ugly racism and its manifestation in the Exclusion Act, the 1882 federal law that barred the immigration of Chinese laborers and required Chinese residents to carry special documents. As a result, Chinese immigrants were both hidden and hated.

Reading newspapers from that time period, Lin learned of an epithet of the era that at first puzzled him.

“The train is coming around the tracks, and ‘John takes off his hat and whoops with joy’ or ‘John is driving ties,’ and I realized that is short for John Chinaman,” Lin says. “That is how everyone who even looked Asian in that time was referred to. And so that to me seemed like a double kind of elision. Not only were these human beings being compressed into a single identity, but then even that was moved into just John. The racial epithet is implied.”

Historical research for the novel was difficult because instead of being described as individuals in U.S. history, Chinese immigrants were described as masses—even an anonymous mass, as indicated by the name John. But Lin continued his deep dive into research and tried to write an individual back into that historical milieu, he says.

“I would be writing a character who people might choose not to see, who might subvert these racist power structures that were in almost everybody, harming him, and how he could actually capitalize on the underside of those power structures.”

Tom Lin’s novel is set during the building of the Transcontinental Railroad, depicted here shortly after its completion in 1869.

The racist power structures against Asian Americans have been around as long as Asians have been in America, Lin says. To write as an Asian American today is to provide a vital voice. And a voice that reveals the false perception of a monolithic Asian American diaspora as it gives utterance to specificity, solidarity and even the act of speech itself.

“I would be writing a character who people might choose not to see, who might subvert these racist power structures that were in almost everybody, harming him, and how he could actually capitalize on the underside of those power structures.”

Tom Lin

For example, Lin notes that his parents emigrated to the United States from Beijing. The Chinese Americans who emigrated here in the 1800s emigrated from the south of China.

“I often had thought if I were to go back in time and meet Ming or his parents, we would have nothing in common between the two of us,” he says. “We would be both Chinese but we wouldn’t speak the same language; we would be mutually unintelligible. And yet we would both be reduced to being Chinese American because we were Chinese in America. That we’re trying to show solidarity and agitate as this kind of fictitious group I think is something that we should never forget.”

Lin says the task of Asian American representation in literature is to show the full gamut of the Asian American experience. Not just the strife and struggles of immigrants. For Lin, those kinds of stories are for white consumption.

He recalls his first year at Pomona when Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, author of Americanah, had come to give a talk.

“She was telling us about the danger of the single story,” Lin says. “And I think that’s extremely apt to describe what representation can do because it can add more stories, and it expands the field of possibility for what people of color can be in the white American imagination.”

For Lin, it wasn’t all about people of color or white Americans. Writing this story brought another satisfaction as well.

“It was just so cool and so satisfying to be working on this story and know that it was a kind of story that I never got a chance to read as a kid. I would have loved this as a kid.”