In those unreal first moments, Zach Landman ’08 wasn’t thinking about college days or his old friends, or the ways in which their worlds were about to intersect. He had no idea of the conspiracy of generosity that would soon envelop his family and help take it to a place of hope that at that instant was unimaginable.

All that Landman was thinking about, just then, were the words he and his wife, Geri, were hearing from their infant daughter Lucy’s neurologist last April.

Rare genetic disorder.

Untreatable seizures.

Never walk. Never talk.

“At the time, Lucy was literally sitting on our laps, this cute, babbling, smiley baby who looks perfectly normal,” Landman says. “The neurologist said, ‘There are maybe 50 kids in the world with this disorder, and it will advance, and the truth is that there is no cure, and from what I can see there is no one anywhere who is working on a treatment.’”

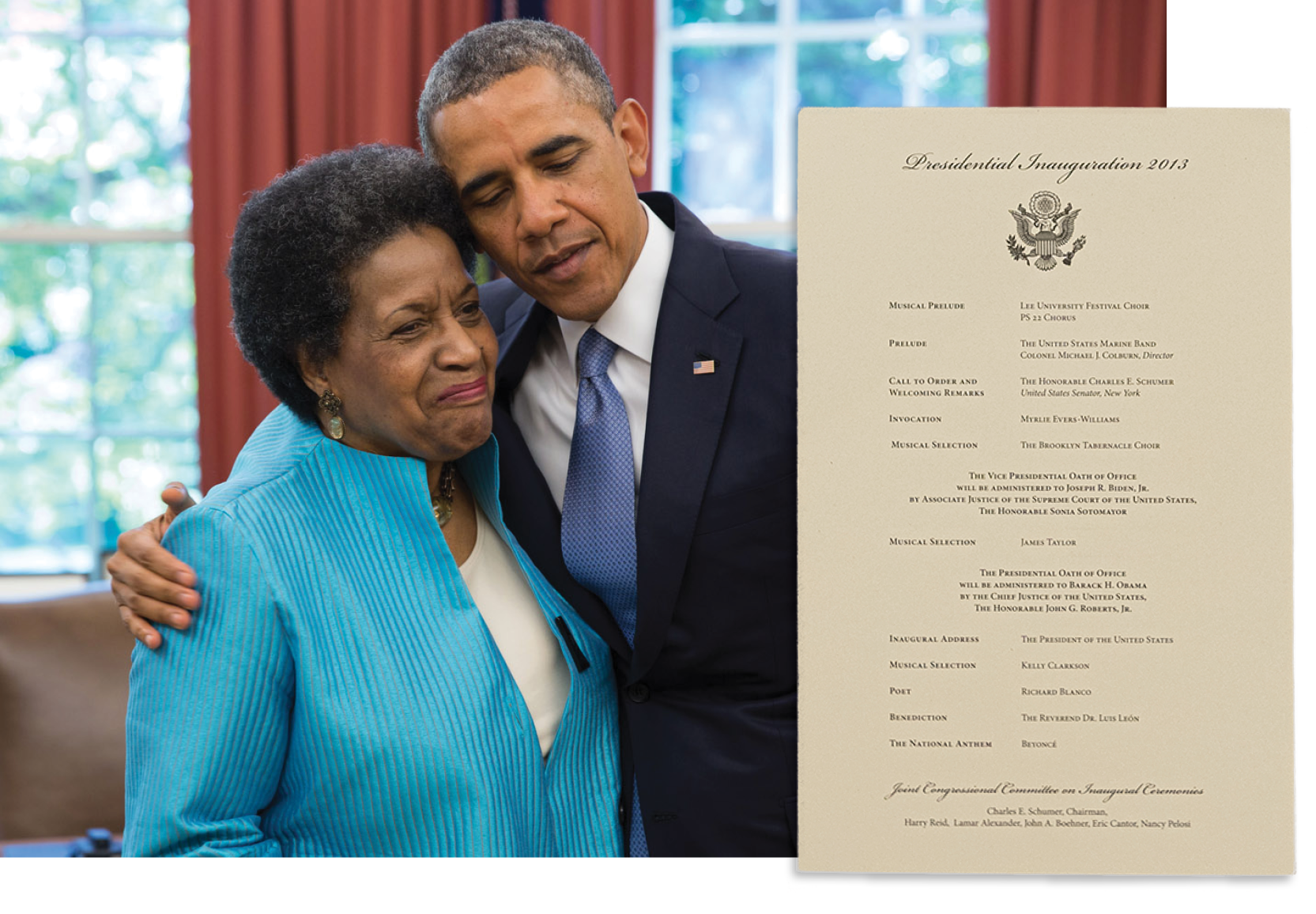

Infant Lucy Landman undergoes a brain scan, one of numerous tests performed at Stanford’s Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital in March 2022.

It was, in those moments, incomprehensible. What followed was a week of soul-searching and tears, as Zach, 36, and Geri, 38, tried to understand by what bizarre turn they had “lost the genetic lottery,” as Landman put it, as dual carriers of a gene mutation so unknown it was only discovered in the last decade. “We’re talking one in billions,” Landman says. “We could have won Powerball several times over before we’d both be carriers for this disorder.”

The diagnosis seemed catastrophic. But Lucy Landman, a blue-eyed doll who was then just shy of her first birthday, got remarkably lucky in at least one specific sense: She is the daughter of Zach and Geri.

Both are doctors, Zach specializing in pain medicine, Geri a pediatrician. It was Geri’s keen sense of baby well-being that tripped the alarms that something was not right with their daughter, with Lucy sometimes unable to remain sitting up, sometimes not making eye contact, sometimes refusing solid food.

Zach Landman ’08, a physician who specializes in pain medicine, spends hours in his home office on research and correspondence related to Lucy’s condition. Photo by Kree Photography

It was Zach’s and Geri’s determination to press experts for answers that led to Lucy’s stay at Stanford’s Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital last March and to full workups, an expedited MRI, a spinal tap, an electroencephalogram, a nerve conduction study. When none of those revealed anything unusual, the pediatric neurologist on service, who also happened to be a geneticist—and Geri’s resident when Geri was at UC San Francisco—moved to the next level and ordered genetic testing.

It led to the chilling diagnosis. But it also led to what came next. A community of help was on its way.

The PGAP3 gene disorder in humans is not particularly well understood, in part because it is so rarely diagnosed. Since no cure exists, it isn’t commonly tested for. What is known is that when the gene fails to function properly, the body does not have enough functional glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) anchored proteins, which are pivotal for both speech and motor development in young children.

“I hadn’t heard of this disorder before,” says Kathrin Meyer, Ph.D., a research scientist and principal investigator at the Center for Gene Therapy at Nationwide Children’s Hospital in Columbus, Ohio, who is working with the Landmans on what could be a cure for Lucy and others like her. “There are very, very few case reports.”

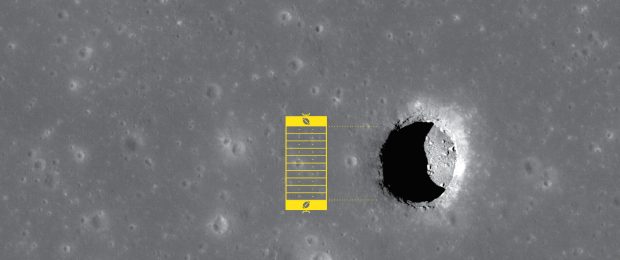

Using lab methods like those seen above, scientists in San Francisco have grown yeasts modified with the PGAP3 disorder in order to test repurposed medicines.

With Zach and Geri both carriers, neither of Lucy’s PGAP3 genes functions properly. Lucy’s parents noticed some of the effects of that as early as four months into Lucy’s life, when the child, their third daughter, showed a tendency to be “floppier” than other children—to sit up straight less often and for shorter periods. But Lucy initially was considered simply to be a later-developing infant with regard to her motor skills. It wasn’t until a family trip to Panama, when she caught a cold that appeared to affect her deeply, that things began to quickly escalate.

“When Lucy started to get really sick in the early spring, refusing food and really lethargic, I started sounding the alarm,” Geri says. “At one point, we were told that they’d scheduled an MRI for her in July. I was like, ‘No, no, no. I don’t think you understand the urgency here.’”

Both Geri and her husband understood, though. With genetic disorders that affect speech and movement, time is always the enemy, because the effects progress so steadily and can become difficult or impossible to reverse. The Landmans’ goals were suddenly both dramatic and incredibly streamlined: They needed near-immediate intervention to slow Lucy’s deterioration of skills, and they needed, essentially, a longer-term miracle—a moonshot, as they put it—in the form of an actual cure.

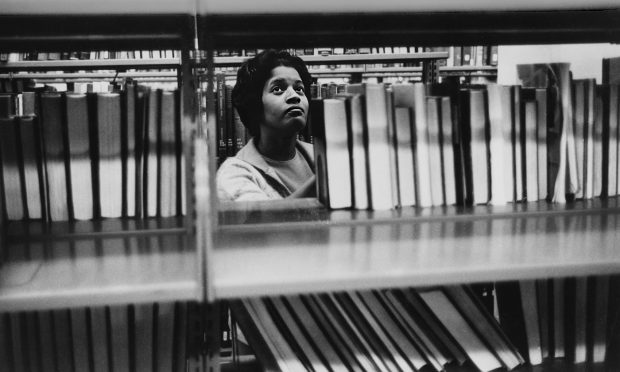

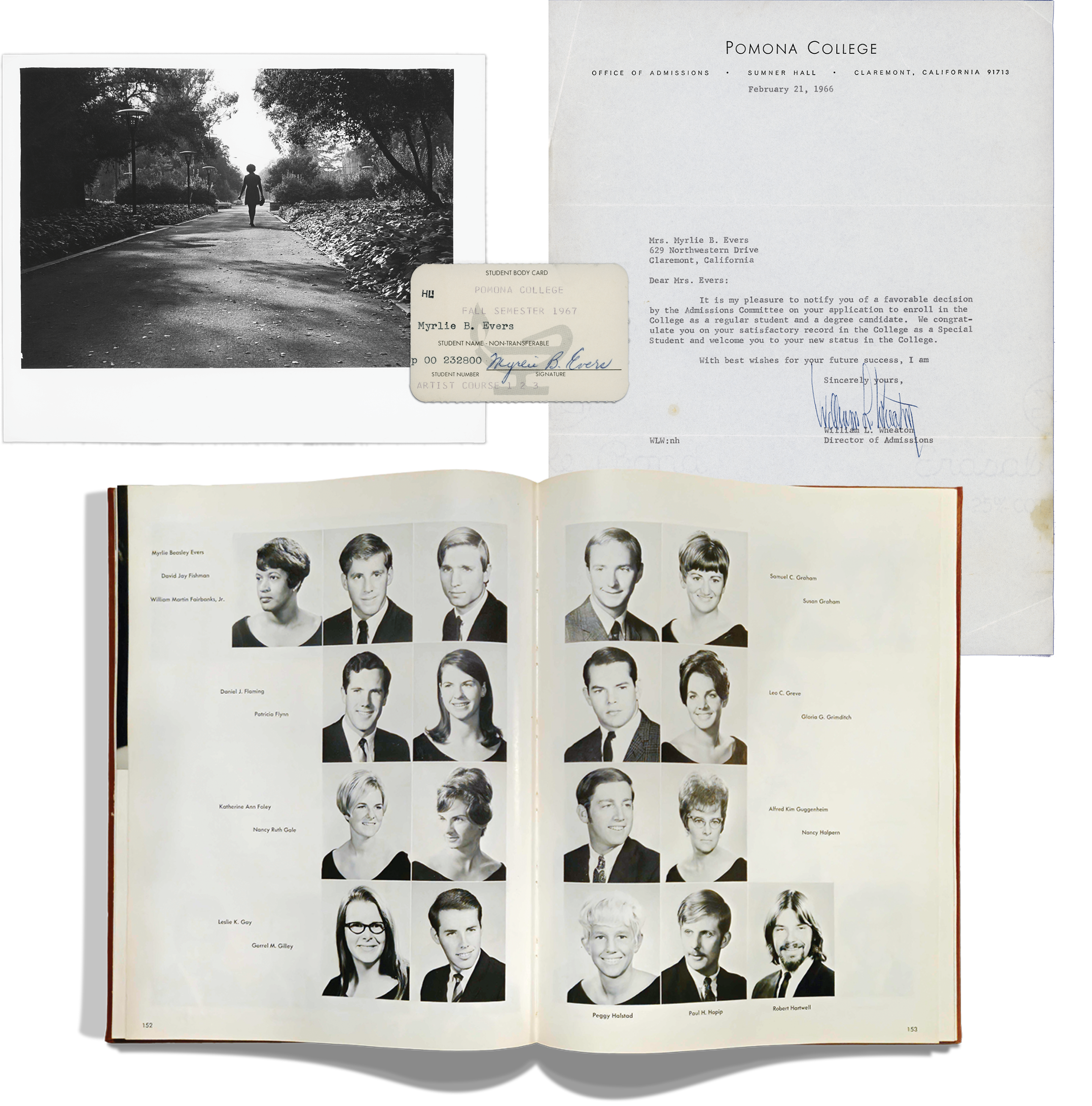

They attacked on all fronts, rounding up expert help from their long lists of personal and professional medical connections: at Harvard, Stanford, Vanderbilt, the Mayo Clinic. Zach, who coincidentally wrote his thesis at Pomona on the application of tailored pharmaceuticals to genetic disorders, began cold-calling experts around the world. Geri, a graduate of Williams College and the UCSF School of Medicine (where she and Zach met), read textbooks on the science behind gene disorders and their treatments.

Kathrin Meyer, in Ohio, was the first to suggest that gene therapy, a process through which healthy PGAP3 genes would be introduced to Lucy’s body to do the work of the faulty ones, might actually work. The Landmans had contacted Meyer because of the deep expertise she and Nationwide Children’s Hospital have in the field, and Meyer explained some of the basics. Lucy’s case was a possibility, in part because a similar therapy Meyer helped develop had worked on a single-gene neurodegenerative disease called spinal muscular atrophy, so a part of a template already existed.

Meyer needed to get Lucy’s cells under a microscope, and although Stanford officials offered to perform a punch biopsy “basically for free,” Zach says, there was significant legalese standing between that act and actually getting the results to Meyer’s team. It would take time to resolve—months, perhaps. The clock was ticking.

“So I took a red-eye flight that night from San Francisco to Atlanta to Columbus, with Lucy on my lap, while Geri stayed at home with the two kids (Audrey, now 8, and Edna, 6),” Zach says. “We Ubered to Nationwide Children’s, met Kat, they found a neurologist to do the biopsy at lunchtime, back to the airport, and then flew home. It was 23 hours of straight travel, but they got the tissue.”

What Meyer needed to know, among other things, was whether Lucy’s PGAP3 gene was relatively long or short. This mattered because the method of transmission to the brain is a virus, and it can accommodate only so large a gene.

“Think of it like a vehicle. This (therapy) is like putting a second car in the garage,” Meyer said from Scotland, where she was attending a medical conference. “If the other car is broken, you can use this one instead.”

The result was affirmative—the transmission method could work. “You won’t believe this,” Geri told Zach after speaking with Meyer, “but this is possible. And she’s happy to get started on it right away.”

In short order, the Landmans realized a couple of truths. First, though gene therapy is inherently uncertain, it was at least a potential cure for Lucy, although it would take 18 months or more to get to a fast-track FDA clinical trial. Second, a couple of other treatments, including the repurposing of existing drugs and a ketogenic diet, might put the development of Lucy’s disorder on a slower track, buying time for that therapy to be created.

And third, this all would cost money. More than they had. Millions.

Zach and Geri immediately started calling pharmaceutical giants, asking if one of them might consider funding the research and trials. The answer came back almost as directly: PGAP3 was so rare that there was no way to make an investment in the gene therapy pay for itself over time.

Geri Landman, a pediatrician, carefully manages her youngest daughter’s diet and supplements. Photo by Kree Photography

After a frustrating week of negative feedback, it was a fellow Pomona grad who helped the Landmans see the road ahead. One of Zach’s cold calls had gone to Emil Kakkis ’82, a physician-scientist who is the founder and CEO of the pharmaceutical company Ultragenyx, which helps produce gene therapies for disorders more common than PGAP3. Kakkis, who knows Meyer professionally, spent an hour with Zach and Geri, laying out the likely scenarios and encouraging them to stay rooted in the present.

“Rather than worry about solving every last variable, which is daunting, the best advice is to keep your head down and get to the next step,” Kakkis says. “If you get a gene therapy created, you will find out what it does and then work from there. It’s an iterative process.”

Says Geri, “Emil just took our hands and slowed us down. He said, ‘You just need to look at tomorrow, and then the next day. Gene therapy is a good therapy. You are working with good people.’ It was a healthy dose of reality.”

Still, the financials of the process were overwhelming; the cost just to get to the point of an FDA trial might top $2 million. It became obvious to the Landmans, who already had sold their Bay Area home and scraped up all their savings, that absent a Big Pharma investment, they’d need to set up a nonprofit in order to solicit funds to help Lucy.

In the midst of their emotional and logistical chaos, Zach and Geri wanted to achieve something greater, too.

“We didn’t want to do it for just PGAP3,” Zach says. “Our mission statement was that we want no parent to get a diagnosis for their child and go to bed thinking there’s nothing they can do, which is what happened to us. It shouldn’t be just two doctors with Silicon Valley connections with the ability to get this done.”

The result: Moonshots for Unicorns, a foundation with a website that not only explains Lucy’s story but notes that single-gene disorders number roughly 10,000 and affect 1% of the population. The cost of developing treatments and strategies for any one of them can run to $5 million. Donations to the site not only help defray costs in Lucy’s case but also fund the Landmans’ creation of a pop-up laboratory in San Francisco that is capable of rapidly testing up to 6,000 existing, FDA-approved drugs to see if any of them can be repurposed—that is, used “off label”—to delay or ward off the effects of PGAP3 or other rare genetic disorders.

Zach and Geri Landman with Lucy, the youngest of their three daughters. Photo by Kree Photography

Simply put, the rarest diseases don’t often get treated or cured because such small numbers of children or adults suffer from them. “But at the same time, you only have one child,” Kakkis says. An organization like Moonshots may one day give that child a chance.

“They’re doing this in such a structured way that it will become a model for others to follow,” says Robert Pepple ’08, who has known Zach since their first day of Pomona-Pitzer football practice together in 2004, the beginning of a longstanding close friendship. “They don’t realize that yet, and I haven’t mentioned it because I don’t want to distract from what they’re doing. But I’m sure of it.

“It’s terrible that this happened to anyone, but there are no two more competent people on Earth to handle the situation,” Pepple says. “They are the most brilliant, motivated human beings in this world. If anybody can figure it out, it’s them.”

It was Pepple to whom Zach turned when it came to organization: How does one even begin setting up a nonprofit? An attorney in the Los Angeles office of the global firm Nixon Peabody who’d been a partner “for all of about five minutes,” Pepple says he told Zach to give him a day, then immediately asked his partners to get on board with setting up Moonshots as a 501(c)(3). “They prioritized it,” Pepple says, and within a day the framework was together.

Pepple didn’t stop there. He quickly reached out to a web designer, who agreed to put together the Moonshots landing site and build out its detailed, expressive pages, all pro bono. The Landmans consistently add updates, scientific information and breathtaking, sometimes heartbreaking, photos and videos.

When another college football teammate of Zach’s, Bobby Montalvo PZ ’10, saw a Facebook post about Lucy’s story on Zach’s page, his first thought was, “They need video.” Montalvo, who owns a production company in the L.A. area, was about to travel to the Bay Area for an assignment. He messaged the Landmans, arranged a sit-down with Lucy, Geri and three cameras, and produced a video that began resonating with visitors to both the website, and now, several social media accounts that update friends and family and seek donations to the cause.

“I had never asked anyone for money or been in a startup mode. Geri and I never even had an Instagram account, you know?” Zach says. “Rob was key. Bobby was key. It’s hard to even explain how much they’ve done.”

Almost a year into their journey, it’s clear that both Zach and Geri still sometimes awaken in a state of shock over the turn their family’s life has taken. When someone mentions to Geri how impressive it is that she doesn’t appear overwhelmed by all they’ve had to do, she quickly cuts him off. “I am completely overwhelmed by this,” Lucy’s mother replies. “I like talking about the science of it sometimes, because it uses the academic side of my brain, not the side that wonders, ‘Who would Lucy have been if she were not missing this one gene?’”

They celebrate the progress when it comes. The Jackson Laboratory, an industry leader in building mouse models for testing specific types of rare disease treatments, offered to do all the model testing and FDA submission on Lucy’s case for free. The keto diet, one often used to treat epilepsy, showed enough promise for the family to consider it for Lucy.

Their fundraising efforts had amassed $495,522 by late fall, in the midst of a “$1.3M by 2023” drive bolstered by nearly 30,000 Instagram followers. Meyer’s gene therapy work continues. And one week after the pop-up lab identified four drugs that might be repurposed to help slow the effects of PGAP3 disorder, Lucy last October took her first steps, something her parents were told would likely never happen.

At each of those points, the Landmans were surrounded by, as Montalvo put it, good people. Geri’s best friend from Williams, Megan McCann, a Wharton MBA, put other business aside to consult and become president of Moonshots. Montalvo sits on the board. Pepple has essentially become a constant—a lifeline of knowledge and action whenever it’s needed.

At each of those points, the Landmans were surrounded by, as Montalvo put it, good people. Geri’s best friend from Williams, Megan McCann, a Wharton MBA, put other business aside to consult and become president of Moonshots. Montalvo sits on the board. Pepple has essentially become a constant—a lifeline of knowledge and action whenever it’s needed.

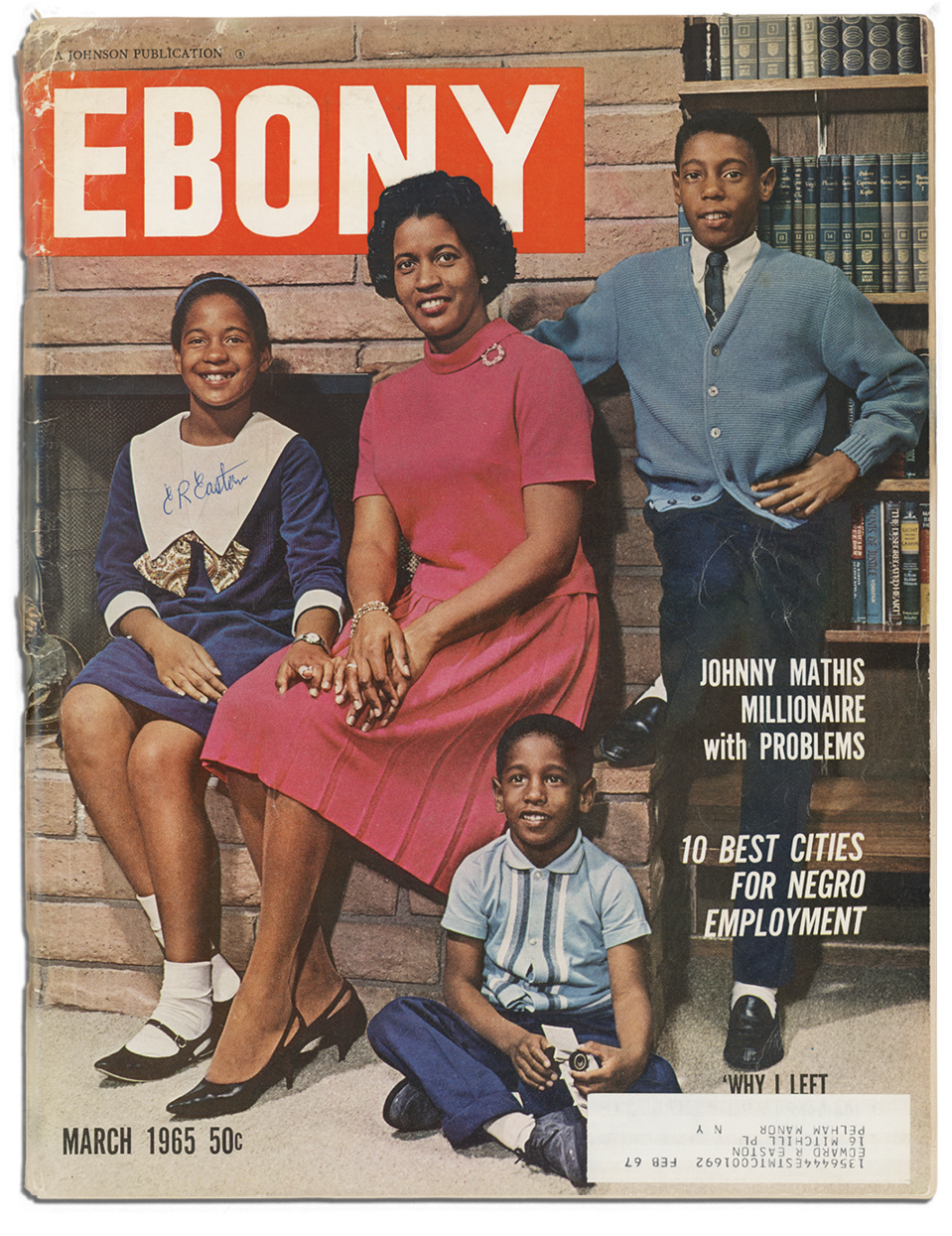

Kakkis, the most veteran of the alumni in the group, sounds unsurprised. “(Pomona) is a small school with lots of good people who care about others,” he says. “It’s more the selection of who is there and the culture of who we are than any networking scheme or clubby-type thing.”

Lucy’s prospects, of course, are uncertain—the nature of a moonshot, Zach says. But her life has already transformed the rest of the Landmans, as well as those who are serving them in the fight. Says Zach, “It spans generations.” It continues still.

Others at Pomona apparently agreed. Brooks won the Ted Gleason Award, given annually to the student who made a warm-hearted contribution to the community life of the College through traits such as sympathy, friendliness, good cheer, generosity and, particularly, perseverance and courage.

Others at Pomona apparently agreed. Brooks won the Ted Gleason Award, given annually to the student who made a warm-hearted contribution to the community life of the College through traits such as sympathy, friendliness, good cheer, generosity and, particularly, perseverance and courage. “Rhizomes are root systems that grow horizontally in unpredictable directions without beginning or end. Rhizomes are always in-process, always growing, always adapting to form symbiotic relationships with existing forms of life. We are a self-organizing system; deeper than grassroots.”

“Rhizomes are root systems that grow horizontally in unpredictable directions without beginning or end. Rhizomes are always in-process, always growing, always adapting to form symbiotic relationships with existing forms of life. We are a self-organizing system; deeper than grassroots.”

At each of those points, the Landmans were surrounded by, as Montalvo put it, good people. Geri’s best friend from Williams, Megan McCann, a Wharton MBA, put other business aside to consult and become president of Moonshots. Montalvo sits on the board. Pepple has essentially become a constant—a lifeline of knowledge and action whenever it’s needed.

At each of those points, the Landmans were surrounded by, as Montalvo put it, good people. Geri’s best friend from Williams, Megan McCann, a Wharton MBA, put other business aside to consult and become president of Moonshots. Montalvo sits on the board. Pepple has essentially become a constant—a lifeline of knowledge and action whenever it’s needed.