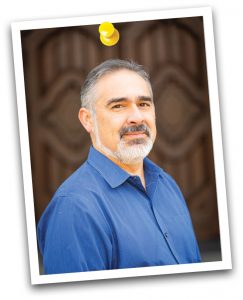

Romero, the new president of the Alumni Association Board, arrived at Pomona in 1987 as an undocumented student. After working in international business, he now owns a marketing consulting firm for small businesses and is a part-time lecturer at Loyola Marymount. His conversation with PCM’s Robyn Norwood has been edited for length and clarity.

PCM: How was it that you first came to Pomona?

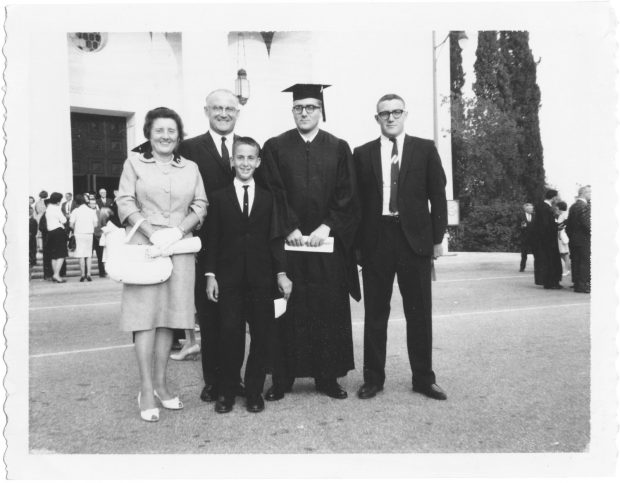

Romero: In high school, I visited the Harvey Mudd campus through the Upward Bound program, where we got to stay overnight. I was very interested in—and still am—engineering and mathematics. During the tour, somebody pointed out, oh yeah, down the street there are other colleges. Pitzer, Claremont McKenna, Pomona. Only one of my teachers at Pioneer High School in Whittier had actually heard of Pomona, and the only reason he remembered was because Pomona had won the College Bowl back in the ’60s. So that added a little bit more mystique. Sure enough, I fell in love once I got to visit the campus, meet people and read about the student-faculty ratio. I thought, absolutely, I’m going to apply.

PCM: Tell me about your family and higher education.

Romero: We’re all immigrants. I was 8 years old when we came here. I didn’t speak a lot of English. One of the reasons that we came to this country, my dad has said many times, is for the opportunities, including educational opportunities. We were a border family. I was born in Hermosillo, the capital of the state of Sonora, just south of Arizona. This was before the borders were so impenetrable. There was a lot of back and forth.

We finally came here, and I was pretty good at school and ended up skipping eighth grade. In high school, they put me in the track of the honors program. It was really interesting, the encouragement I got from my parents. It wasn’t even explicitly said, but I understood that whatever I chose to do, they were going to support it. It never really dawned on me to think about the price. We’d figure out how to pay for it. I’d take loans if I had to, which I did. There are a lot of things I wish I would have known. But I also had probably the best support I could have gotten.

PCM: How did you get involved on campus once you were here?

Romero: I spent my first two years in Oldenborg, and that was a lot of fun. I was very involved in high school and I just continued that here. I decided to run for ASPC, so I was a senator and then I was the external affairs commissioner my junior year. I played intramurals. I’ve always been very sociable, so I’d just go meet people. A lot of the people on the Alumni Board are people who were very involved. In fact, we have former ASPC presidents on the board, including Andrea Venezia [’91], who was ASPC president when I was here. My personal journey after graduating was that I volunteered with the CDO [Career Development Office] quite a bit. And I served on panels about business, international business, graduate school, anything they needed speakers for that I have experience in.

What it’s always been about is Pomona did a lot for me. Coming in, I was actually undocumented. I didn’t get my green card until I was a sophomore at Pomona. Thinking back, that was probably one of the reasons I chose Pomona over UCLA—a state school versus a private school. I never got to the conversation with UCLA as to what they would have expected of me as an undocumented student, but with Pomona there was no issue. Some of the loans I got were different from federal loans, but they found them for me.

That’s probably one of the biggest debts of gratitude I have to Pomona: They didn’t let my immigrant status get in the way. But the other one is really just the exposure to the world that I got at Pomona. Students from all over the world, all over the country. The access to different socioeconomic groups. I think one of the best advantages Pomona has, especially with the diversity of the student body, is that as a young immigrant kid from Whittier, you get to speak with people whose parents are professors or they’re lawyers or they’re successful business people. There are also instances where you realize that you’re in a better situation than they are, which for a 17-or 18-year-old is eye-opening when you’ve been told your whole life that people in the upper part of the socioeconomic strata have it better: They have a better life; they have a better chance of success.

The story I love to tell is the friend of mine who needed to buy a dress for a formal party. We went down to Montclair Plaza. I had a car, and that was one of the biggest things right? I’m local, so I have a car and I drive people around. There are different kinds of privilege. We get to the mall, she picks the dress she wants and we go up to the counter. Her father had given her a checkbook and said, “Go ahead. Write checks for anything you need.” Which immediately I’m thinking, oh, that’s cool. She opens up the checkbook and goes, “I don’t know how to write a check.” It was a big reveal to me, because I had a checking account since I got a job at 16. So I helped her. Privilege isn’t necessarily a binary thing. It’s not one extreme or the other.

PCM: Given the timing, were you part of the Reagan amnesty era?

Romero: Yes, absolutely. We came here in 1978, and my dad actually had attended high school in Arizona, in Tucson. He joined the U.S. Air Force but ended up moving back to Mexico, met my mom and had a family there. When we came, my dad said, “I’m a veteran. We should have no problem immigrating.” So we started applying for residency. And nothing. It was issues with my dad’s paperwork; there were just all kinds of hurdles. It was seven, eight years of trying. My mom was completely concerned when I was in high school. “Be careful where you go, you don’t want to get caught by Immigration.” At that point, I think I’d already lost any accent I had, so I wasn’t that worried. But my mom was.

At one point, the lawyer we had hired to help us looked at my parents and said, “You know, the best thing you could do right now is to apply for this new amnesty program that is coming through.” So when I hear people talking about, like, why don’t people just come here legally, I remember it took us almost a decade to do it the right way. That is how finally, in 1987, I was in Oldenborg and I got my date to go down to the city of Pomona and have my interview to get my temporary residence card.

PCM: With the Alumni Board, do you come in with anything specific you’re trying to do?

Romero: The Alumni Board to me is a reflection of the alumni community as a whole. So what I immediately recognized is that no matter what my personal feelings may be towards something, the only way to get things done is to make sure the energy is there to get them done. Yes, I have a particular passion for DACA students or anybody undocumented. I have a very, very strong desire to help first-generation and low-income students as they come in. We do have a very diverse group on the board, including other former first-generation students.

But we also have—I guess I’m part of this now—older alumni who are very interested in continuing the traditions of the College. In conversations with some of the younger alums, there seems to be a disconnect between their experience at Pomona and what they see as the traditions of the College. Some of that was done on purpose because there are some traditions that Pomona had—the freshman weigh-in was definitely one we don’t want to continue. It stopped. But there are a lot of traditions that we do want to continue. (For more on traditions, see Pomoniana Blog)

Julian Nava ’51, a professor and trailblazing advocate for public education who later became the first Mexican American to serve as U.S. ambassador to Mexico, died July 29, 2022. He was 95.

Julian Nava ’51, a professor and trailblazing advocate for public education who later became the first Mexican American to serve as U.S. ambassador to Mexico, died July 29, 2022. He was 95. Message from Alumni Board President

Message from Alumni Board President

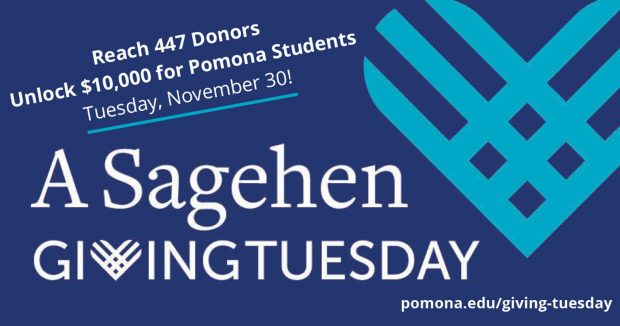

Thank you for your care and support of our Sagehen community!

Thank you for your care and support of our Sagehen community!

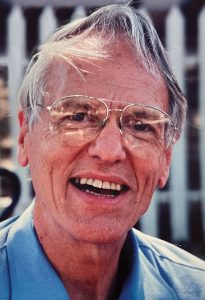

A professor at Pomona for nearly 40 years, McDonald taught government and political theory from 1952 to 1990, serving as dean of the College from 1970 to 1975. His daughter Alison McDonald ’74 recalls that during his years as dean, McDonald enjoyed working closely with President David Alexander and other administrators. But he always said that being an administrator meant “saying no” and he found it hard to say no. After five years, he returned to teaching, which he loved.

A professor at Pomona for nearly 40 years, McDonald taught government and political theory from 1952 to 1990, serving as dean of the College from 1970 to 1975. His daughter Alison McDonald ’74 recalls that during his years as dean, McDonald enjoyed working closely with President David Alexander and other administrators. But he always said that being an administrator meant “saying no” and he found it hard to say no. After five years, he returned to teaching, which he loved.

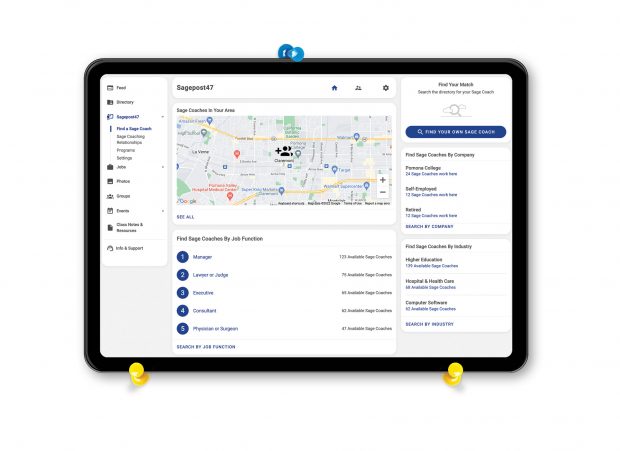

Watch your email and mailbox for more information on these upcoming events. To update your contact information, please email

Watch your email and mailbox for more information on these upcoming events. To update your contact information, please email