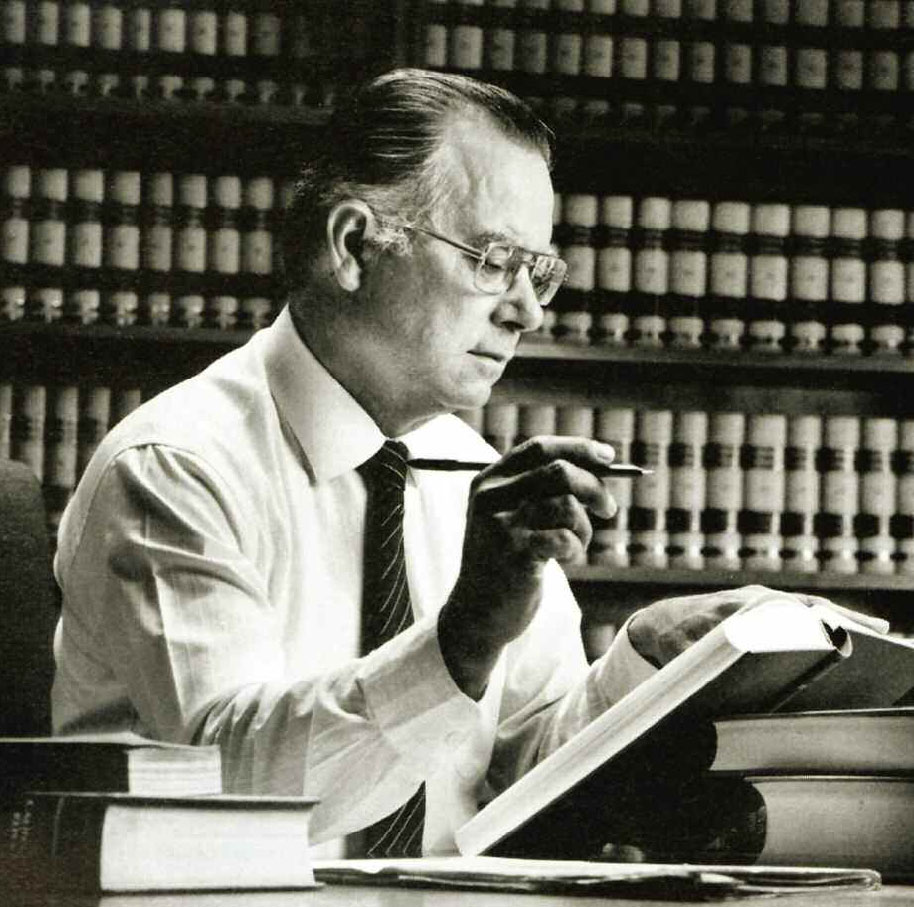

Cruz Reynoso ’53 during his time on the California Supreme Court

Since the 2010 release of an award-winning documentary about his life, Cruz Reynoso ’53 has been appearing with producer- director Abby Ginzberg at high school, college and law school screenings around the country. But the 80-year-old, who led a ground-breaking fight in the ’60s for the rights of farm workers and served as the first Latino justice on the California Supreme Court, has not stopped for long to look back.

An emeritus law professor at UC Davis who still teaches one semester each year, Reynoso is spearheading two investigations— one into the death of a young farm worker shot by police and another into the pepper-spraying of students at UC Davis during a peaceful protest last fall.

“I’m too active,” says Reynoso with a laugh. “I’m also a member of the board of California Forward, a group that is trying to reform our dysfunctional state government. One of the things we are trying to do is get an initiative on the ballot this year to reform how the budget is put together. We realize how difficult it is to do anything, and we’re prepared for failure. But we have to try.”

That persistence is illustrated in the new documentary about his life. Shown on PBS stations nationwide and recently released on DVD, Cruz Reynoso: Sowing the Seeds of Justice (www.reynosofilm.org) combines archival footage and interviews with Reynoso and his contemporaries to tell the story of a turbulent time in California and U.S. history. “What makes biographies interesting to me is the historical period in which a person lived,” says Ginzberg, a former attorney who has been making documentary films for almost 20 years.

One of 11 children, Reynoso grew up in Southern California, working in the orange groves alongside his parents. At 16, he made what Ginzberg describes as the most pivotal decision in his life, when he chose to pursue an education, despite his mother’s wishes that he continue working. A scholarship brought him to Pomona College and, after serving in the military, he went to law school on the G.I. Bill at UC Berkeley, where he was the only Latino in his class.

After graduating, he started a small law practice and joined the Community Service Organization, where he met Cesar Chavez. It would be the first step in a life devoted to public service. “One needed to do something beyond simply having a job just to support your family,” says Reynoso in the film. “That was important. But the community and what was happening around you was always important to me.”

In 1966, he was named director of California Rural Legal Assistance, Inc. (CRLA), the first legal aid program aimed at helping the rural poor. The success of CRLA drew the ire of agribusiness and Gov. Ronald Reagan, who vetoed funding for the program and accused it of undermining democracy. Reynoso led a successful three-year court battle to overturn Reagan’s veto and is credited for helping to save the organization. “I think the fact there is an institution still there defending workers is a testimony to the ability of people like Cruz to navigate the shoals when you have enemies like Gov. Reagan,” says Jerry Cohen, a former general counsel to the United Farm Workers Union who was interviewed for the documentary.

Ginzberg calls Reynoso an unsung hero of the legal profession and describes him as calm, focused and vigilant, even during the most trying periods of his career. ”He could rise to the temperature of the moment, but he never raised the temperature, and that really made a difference,” says Ginzberg.

Appointed by Gov. Jerry Brown to the state Supreme Court in 1981, Reynoso again became a political target, when supporters of the death penalty and business interests mounted a campaign for a statewide retention vote that ousted Chief Justice Rose Bird, Justice Joseph Grodin and Reynoso.

“With respect to the attacks on the court, I never took it personally because I knew the attacks were false,” says Reynoso. “Sad to say, those who were attacking the courts were very vigorous, and those defending the court had never been involved in that type of issue before, so they were in disarray. Most of what voters heard were attacks on the courts, particularly that we were not following the law. I told people if I believed what was being said, I’d vote against me.”

“Cruz was the first Latino on the California Supreme Court, which was one of the biggest honors you could have, and then he suffered one of the biggest defeats four years later,” says Ginzberg. “Neither one defined him. His attitude was: what can I do next? He didn’t sit around licking his wounds.”

In 2000, Reynoso was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Bill Clinton. The following year, as vice chair of the Civil Rights Commission, he led the only official investigation into voting irregularities in Florida in the Bush-Gore presidential election.

As a professor, Reynoso has become a role model to a new generation of idealistic young attorneys, says Ginzberg, who admits she too has been influenced by the subject of her film. “I’ve sort of adopted his view. He told me, ‘I’m an incurable optimist. If I weren’t, I wouldn’t be able to do half the things I’ve done in my life.’ Cruz also says that you can’t think something is going to be easy, or because you win one battle you’re not going to have to fight another. Justice is a constant struggle and we have to keep fighting.”

Reynoso says he sees that same need to keep fighting reflected in the students he’s met as a professor and during his travels with Ginzberg. “My life is simply a continuum in terms of the many hundreds and thousands of people who’ve come before me, who have been struggling for human rights, for social justice,’’ he says. “I see it in the faces of those young people who will continue the struggle. It confirms my notion that things are never still; they’re always moving, and we have to be there to protect those who don’t have economic or political power.”

CRUZ REYNOSO ON:

THE OCCUPY MOVEMENT: “I have really been pleased to see the Occupy Movement because it came at just the right time to balance the political scene. The reality of the last 20 to 30 years is that the rich are getting richer and the poor are getting poorer and the middle class is disappearing, and that is not a good thing for a democracy.”

EDUCATION: “Education is a key to doing well in society. I hate to use harsh terms, but we’ve practically become immoral by placing the financial burden for education on the people least able to pay—the students—instead of having us as taxpayers, who are working or who have retirement pay, carry that burden. It’s so different from what we’ve done in the past.”

JUSTICE: “As a youngster I had what I called my justice bone. When I saw something that was really unfair or unjust it hurt, and so I felt compelled to do something about it to relieve that hurt. And I think that is still true today. So in some ways, what I do is a selfish effort to not hurt by taking on some of those issues.”

GOVERNMENT: “We’re now having a debate about whether the government should be big or small. I’ve always thought in a democracy that government should do what people want it to do irrespective of those descriptions of large and big. In some instances, big programs might be good, in others, small programs might work.“

THE GOOD FIGHT: “I have always felt that even if you lose a good fight, you have gained something by helping educate people about the issue. So, hopefully, you win a number of the battles you’re in, but even when you lose, you’ve done some good. Those of us who feel strongly about those issues have a duty to continue fighting, and I find that invigorating.”