I realized my mistake as I sat sweating and gasping for breath, knees trembling, body strapped into a bare-bones racecar with more horsepower than I wanted.

At the twirl of the instructor’s hand in the air, I flipped two of the six switches that comprised the entirety of the racecar’s dash controls. The vehicle rumbled to life, shaking and coughing at idle in a way that let you know it would only be happy going fast.

I hadn’t wanted to go to racing school. I’d rather not go fast, and I’m not the physically adventurous type. The only boundaries I like to push are how many books I can read in a week. But I’d had the idea to write a mystery series set in the car racing world after working in corporate marketing for a racing series sponsor. The fact that I’d never written a mystery—that I’d written fiction for the first time in my life only a few months prior—hadn’t stopped me from pitching my nascent idea to a published author. She encouraged me, with one caveat: My sleuth, who I’d seen as a woman in corporate marketing, had to be the racecar driver.

I hadn’t wanted to go to racing school. I’d rather not go fast, and I’m not the physically adventurous type. The only boundaries I like to push are how many books I can read in a week. But I’d had the idea to write a mystery series set in the car racing world after working in corporate marketing for a racing series sponsor. The fact that I’d never written a mystery—that I’d written fiction for the first time in my life only a few months prior—hadn’t stopped me from pitching my nascent idea to a published author. She encouraged me, with one caveat: My sleuth, who I’d seen as a woman in corporate marketing, had to be the racecar driver.

I needed the knowledge I’d get from being behind the wheel, and I wanted to have done it, even if doing it scared me to death. So there I was in the car at Road Atlanta, a road course in Georgia. Panicking.

We’d started the three-day course with classroom work, which is the kind of thing I’m good at, even if the topic was tire contact patches and the forces involved in cornering and braking. But then they put me in a car, and told me to forget everything I thought I knew about driving.

The first hands-on exercise was learning to brake, which should have been a no-brainer. What’s different about braking on the track, however, is that you don’t ease onto the brake and ease off, as you would in a street car rolling to a stop at a light. In broad strokes, racecar drivers want to be 100 percent on the throttle until they’re 100 percent on the brakes.

That meant barreling toward the brake markers at full acceleration—and then standing on the brake pedal with all my might, hoping to God I didn’t run into the gravel trap or, worse, the wall at the outer edge of the turn. Every fiber in my body screamed at me to brake sooner while my brain countered with “they said not to brake until the next marker.”

After braking, we learned how to heel-and-toe downshift. That’s using the right foot on two pedals at once, to both brake and blip the throttle (press the accelerator), which raises the engine revs so the car doesn’t lurch when I release the clutch. The point is to be as smooth as possible—“smooth is fast,” one driver told me—and maintain the connection of the tires to the ground at all times.

I kept telling myself that if I could tap dance (which I can), I could heel-and-toe downshift too, even if tap dancing doesn’t usually happen at 80 mph. I managed it only once the first day.

At this point in the instruction, I should have taken comfort in the fact that the other students were in the same boat, all beginners, all learning—except that they weren’t, because three of them were NASCAR drivers, young guns recently hired by one of the top NASCAR bosses through a televised reality show.

They were there to brush up on their road-racing skills, since their experience mostly ran to ovals. I’m sure intimidating an already scared writer was all in a day’s work for them.

Unlike me, the NASCAR boys had no trouble putting all the pieces together when it came time for a lead-follow around the track with an instructor showing us the correct line and braking points. They performed well; I floundered. It was the second day, and we were in groups of three cars (one student per car) following an instructor who was a professional driver. We were supposed to hit each apex correctly, upshift to the gearing they’d told us was correct, brake where they told us to brake and heeland- toe downshift.

Another attendee was frustrated with my pace and dogged my back bumper, which didn’t improve my skill. But I simply wasn’t ready to go as fast as the other two drivers in my group, and I stuck to my own comfort level, trying not be peer-pressured into a speed I wasn’t ready for. A good friend and professional driver had counseled me to take things at my own pace, and I repeated her words to myself as I struggled through our sessions.

Sooner than I wanted it to, the moment of truth arrived: my first solo laps. I sat waiting in the rumbling car, sweating and terrified, hoping my shaking legs would be able to work the clutch and throttle. I wondered again why I was doing this and why I hadn’t chosen something more normal and less violent to write about besides racing. Tea parties and embroidery, perhaps. And then they waved me out.

Sooner than I wanted it to, the moment of truth arrived: my first solo laps. I sat waiting in the rumbling car, sweating and terrified, hoping my shaking legs would be able to work the clutch and throttle. I wondered again why I was doing this and why I hadn’t chosen something more normal and less violent to write about besides racing. Tea parties and embroidery, perhaps. And then they waved me out.

The change didn’t happen right away. As I lapped the track in short stints, punctuated by feedback from instructors stationed at different corners, I slowly began to enjoy myself. To find myself grinning under my helmet because I enjoyed the section of the track that curves left and right like the letter “S.” To think more about doing every corner right the next lap, not just three of 12. I got comfortable enough to relax, process more information and handle the speeds. I still wasn’t fast, relative to other students in the school. But I was doing 90 mph before braking for one corner, going 75-80 through another corner, and hitting 117 on the back straight. Best of all, by the start of the third day, the instructors were telling me I was doing everything right. That even if I wasn’t fast, I had the right skills. Going fast just takes more seat time, they assured me. I’ll take their word for it.

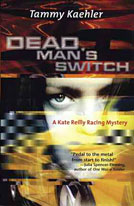

In the end, I learned enough to make my racecar driver sleuth, Kate Reilly, credible in the eyes of the racing world. Even if I can’t drive the way Kate can, I understand how she does it, and I can make her a character that the racing world believes in—in part, thanks to one of the instructors who later reviewed and blessed the driving scenes in my novel. I also faced down my fears and made it through one of the toughest challenges in my life.

But the truly eye-opening moment came near the end of the three-day course, when I rode in the racecar I’d been driving, with an instructor at the wheel. That’s when I understood how much more potential there was in the car and the track, and how much farther away the dge was. That two-lap ride gave me a glimpse of a different world, one of extreme speed and control and daring.

I know I’ll never personally inhabit that world, but at least now I can write about it.

ABOUT TAMMY KAEHLER ’92

She fell into the world of auto racing—and landed in the VIP suites. Kaehler had a freelance gig writing marketing copy for a mortgage lender during the housing boom of the early 2000s. When the lender decided to help sponsor the American Le Mans racing series, Kaehler saw a chance to travel and look inside another world, so she signed on to help with corporate hospitality work at the races.

Since she was working for the company putting up the cash, Kaehler got inside access at the track, riding in top-of-the-line Porsches and meeting “everyone and their uncle.” She became fascinated with auto racing: the money, the violence, the rock-star drivers.

Since she was working for the company putting up the cash, Kaehler got inside access at the track, riding in top-of-the-line Porsches and meeting “everyone and their uncle.” She became fascinated with auto racing: the money, the violence, the rock-star drivers.

Soon she was at work on a racing-themed murder-mystery book featuring a female racecar driver, Kate Reilly. After the mortgage company went bust, she kept at her writing and kept her toes inthe motorsports world, volunteering at races. When Dead Man’s Switch finally published last year, she launched the book at the American Le Mans Series at Connecticut’s Lime Rock Park, where the story is set.

Since then, her author events have continued to zigzag between conventional mystery book venues, where the racing aspect of the book stands out, and book-signings at racing events, where the mystery aspect is unique. “At each, people are totally fluent with one aspect of what I’m writing about,” she says.

Following this unusual course, Kaehler has found her audience. Publishers Weekly and Library Journal both praised the debut, and the second Kate Reilly mystery will be published next year.