In today’s session of Flashpoints in Rock ‘n’ Roll History, Professor Kevin Dettmar recounts the 1980s rise of Irish rock band U2 to peak popularity with The Joshua Tree. The band becomes known for its sincerity and social consciousness, but Dettmar notes questions to consider regarding how U2 goes about promoting its causes.

The professor plays U.S. concert footage from U2’s 1988 Rattle and Hum documentary in which the band performs an extended version of its early anthem “Sunday Bloody Sunday,” about the conflict in Northern Ireland. Lead singer Bono interrupts the song with a fiery speech: “Irish Americans who haven’t been back to their country in 20 or 30 years come up to me and talk about the resistance, the revolution. … What’s the glory in taking a man from his bed and gunning him down in front of his wife and his children? … No more!”

That sets off the classroom discussion, abridged and edited here. Does the midsong monologue undermine the music— and the message? Can Bono’s American concert audience even grasp what he’s talking about?

DETTMAR: So tell me what you saw …

WILLIE: Bono was very emotional throughout. That’s part of what makes him such a good performer. He was becoming really close with his audience, talking about the terrorism in his country.

LEE: The monologue in the middle just seems kind of over the top. If I had gone to see a band I really like I would mostly be going there to listen to their music, not to have them tell me about how I should change the world.

DETTMAR: I think that the band and Bono, they have the best of intentions. … But you can question their strategy. Part of the problem with these sermons in the middle of songs is they are implicitly saying the songs aren’t powerful enough to do the work that we want them to do: We don’t trust the song to carry the message.

SHERIDAN: The song keeps losing its momentum. All of a sudden Bono starts talking and preaching for two minutes. Then the song ends. Then they start playing again. They’re trading off the actual musical quality for the preachiness and the message.

SARAH: Maybe they don’t trust their songs to carry the message, but people in America do have a really big problem with not knowing what’s happening outside of the U.S. I think this is one of the ways, maybe, that they can get people’s attention.

DETTMAR: The problem is that if you don’t understand the political situation—if you don’t understand that they’re from Ireland and that the violence is actually in Ulster, for instance—then what he says is too telegraphic. You’re never going to understand it.

BEN: I find it interesting that people react against Bono being “preachy.” Without that preachy nature, what is U2?

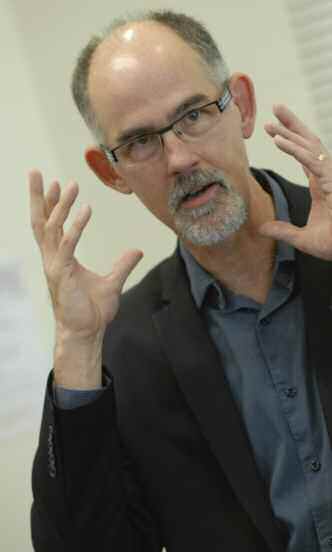

The Professor: Kevin Dettmar

At Pomona since 2008, Kevin Dettmar is the W.M. Keck Professor of English and chair of the English Department. He splits his research and teaching between British and Irish modernism, with an emphasis on James Joyce, and contemporary popular music. He is the author of Is Rock Dead?, editor for Oxford University Press of the book series Modernist Literature & Culture and general editor of the Longman Anthology of British Literature.

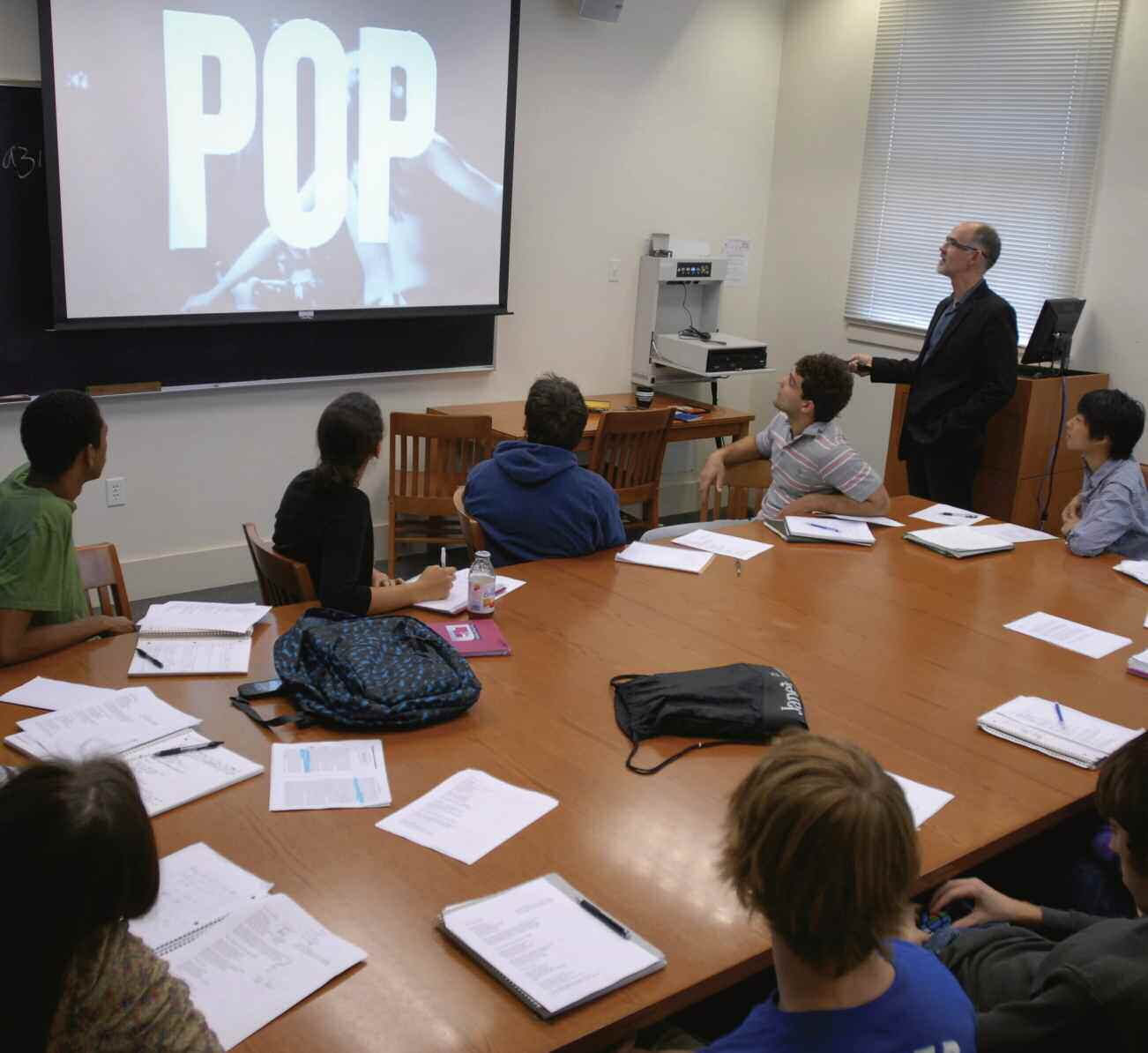

The Class: Flashpoints in Rock ‘n Roll History

Rock ’n’ roll has both endured and enjoyed a rocky public reception since its earliest days: Bill Haley & the Comets’ “Rock Around the Clock” (1954) provoked riots across the country. We will trace the “scandalous” history of rock ’n’ roll through its public controversies. In such moments, we learn a great deal about what rock hopes to be, about its intrinsic contradictions and structural instability, and about the resistance it meets from its own fans.