When the COVID-19 pandemic forced the College to evacuate its campus a year ago, the Class of 2020 was stunned—perhaps more so than their younger peers. This was their last semester on campus, a busy one but also a fun one— it was supposed to be the semester to end all semesters. But on Wednesday, March 11, an email appeared in all their inboxes, announcing the closure of campus as the COVID-19 outbreak brought Los Angeles County, along with the rest of California, into a state of emergency. Suddenly, all their expectations were turned upside down.

Their final months as Pomona College students were spent off campus, either back home with family or in new living arrangements with friends and roommates. As the pandemic worsened, economic forces began to affect the job market while tightened university budgets constrained graduate programs.

Pomona College students in general fared well, according to a Career Development Office survey released in February that showed 90% of the Class of 2020 graduates participating in career activities—such as a job, internship, service opportunity, graduate school, fellowship or other related activity.

To dive deeper, we spoke to six recent graduates from the Class of 2020, who shared how they have managed in the months since graduating from Pomona. Spanning disciplines and industries, these Sagehens have endured their fair share of experiences that are unique to the year of the pandemic. These are their stories.

Karla Ortiz

“I’ll Figure Something Out”

“Growing up, my parents were always telling me: ‘We don’t want you work with your hands—we want you to work with your mind,” Karla Ortiz recalls. As immigrants, however, her parents knew little about college or scholarships, so Ortiz had to figure out everything on her own. “All I knew was how to get good grades and that I’ll figure something out.”

On March 11, 2020:

Karla Ortiz, a Chicana/o-Latina/o Studies major and math minor, was in the interview process for a paralegal/legal assistant position and had a few other résumés out for jobs in the legal and nonprofit fields.

And she did. As a QuestBridge Scholar, she earned a fully paid scholarship to Pomona, starting out on the pre-health track. After a full year of biology and chemistry, when she decided pre-health wasn’t for her, a methods course in Chicana/o-Latina/o Studies (CLS) soon filled the void. “I felt a very big sense of community that I hadn’t felt in any other classes. … In CLS, I felt I was being heard and understood, and so I decided to major in that, with a focus on immigration.”

She became a Mellon Mays Undergraduate Fellow and volunteered at a nonprofit, Uncommon Good, where she tutored and mentored youth. She took a leadership role with the First-Generation and Low-Income (FLI) program.

When the pandemic hit, Ortiz—who was set to graduate with a major in CLS and a minor in mathematics—again had to figure things out. She was in the middle of interviews for a paralegal position when entry-level openings began to disappear. Suddenly, the replies to her cover letters read along the lines of “We are no longer hiring for this position” and “We are freezing hiring for the time being.”

With her parents’ words in her ear, Ortiz never stopped giving it her best, even as her options dwindled. Anxious about not having a job lined up, she signed up in May for an online platform for jobs in education at independent and charter schools. A director of a private school in the Bay Area contacted her personally. “He said he saw my résumé and that I’d be a great fit.” As it turned out, he was particularly interested in Ortiz’s chemistry background—her first year of chemistry and her sophomore year when she became a mentor to a chemistry cohort for underrepresented first-years at Pomona.

“And so, we just went through the interview process: three interviews, got a reference from my chemistry professor, and they talked to another professor about my skills. I got the offer in the beginning of August, and the first day of classes was the 24th.”

A two-year teacher training program at the private school paired Ortiz with a mentor in the same subject, and her first few weeks were spent observing pedagogy in action: how the teachers interacted with students, how they taught the material, how to plan lessons. Now she’s teaching her own classes in ninth-grade chemistry—remotely at first, then as a hybrid mix of virtual and in-person learning.

Trained in CLS, Ortiz has keenly observed the disparities between her own experience as a pupil at an underresourced public high school in Las Vegas, where school lunches often involved semifrozen burritos and other heavily processed foods, and the private high school world in the heart of Silicon Valley where she now teaches. No frozen burritos here—fresh and healthy ingredients are the norm as cooks prepare wholesome meals for the students and staff.

Ortiz is not sure what the future holds. She plans to continue teaching through the end of the training program, arming herself with the knowledge and experience for teaching at the college level one day—perhaps. But she’s also considering business school, a career route she’d never considered before the pandemic. “Money is tight, and business school has crossed my mind.”

Business school. A Ph.D. in sociology. A policy degree. Ortiz continues to mull over her future choices, knowing she will figure something out. But in the meantime, it’s back to ninth-grade chemistry.

Kyle Lee

“An Exercise in Being Vulnerable”

Kyle Lee is an extrovert by nature. An actor who took to Seaver’s stage as a theatre major, he also mastered the art of walking backwards while giving campus tours for the Admissions Office.

On March 11, 2020:

Kyle Lee, a theatre and clinical neuropsychology double major, had just returned from a final callback for an MFA program at UC Irvine and was excited to be in the midst of the admission process with a number of notable MFA programs.

“I’m a people person,” says Lee, who also designed a second major, clinical neuropsychology, in order to better understand people. While at Pomona, Lee thought he knew himself well. Then the pandemic surprised him with the hustler living inside him, as he puts it—the Kyle who makes things happen.

In the fall of his senior year, Lee had applied to a number of MFA programs in acting. He had spent hours and hours preparing monologues and getting ready for auditions, and he got final callbacks at a number of good schools. Excited about each and every one of them, Lee was feeling good—very good—about himself in the weeks leading up to that fateful spring semester, when everything changed.

He stopped hearing back from the programs around the same time Pomona began evacuating campus. When the programs emailed him again, it was a series of depressing messages. “Programs were emailing saying they had either closed or were no longer going to happen. These programs already only take about eight students, so now some are only taking four or six. Most programs just didn’t happen.”

The blow was a harsh one. “Honestly, there were a lot of times when I was wondering why I got this degree. I felt my skills were not useful … but it’s a pandemic and I had to learn to give myself grace.” Ongoing therapy and a close-knit group of friends going through similar struggles helped Lee get through it all.

In the weeks leading up to the announcement that all students must vacate campus, Lee didn’t believe things would be that bad. The shock of the evacuation took him aback. At first there was anger toward the College administration over the decision to evacuate. Then came fear. Lee wasn’t able to return home to New York. “I felt I was being left out in the cold. My mother is housing-insecure, and she was like, ‘I don’t know where you’re going to live.’”

Mixed with the fear was uncertainty. “I was on the precipice of the unknown. I hadn’t heard from my MFA programs, and I didn’t know where I was going to be. I was not sure if our [Pomona] jobs would keep paying us. Honestly, I wasn’t even thinking of graduation or the social aspect of things. I was just trying to figure out how to survive. I packed my stuff, and I just sat in the back of a car not knowing where to go.”

Lee ended up in Los Angeles after calling a friend, Miles Burton ’17, who had an extra room in an apartment he was sharing with another person. The room was spoken for, but Lee was welcome to stay there until the new roommate moved in. Lee was grateful for the respite, but the uncertainty of his life continued to hit him in waves. What followed were many weeks of despair and wondering how he would be able to afford his new rent and bills.

The job search in a pandemic was plainly and simply hard, says Lee. He took on various gigs to pay the rent: delivering food for Postmates, coordinating a training for a startup, becoming a freelance writer for a get-out-the-vote campaign in Georgia.

Even with his gregarious nature, Lee was hesitant to ask for help. But in early fall of 2020, after months of gig jobs and stressful thoughts, Lee reached out to his beloved Office of Admissions at Pomona, where he had worked for many summers and where staff members had taken him under their wing.

“I was like, ‘OK, Kyle, this is an exercise in being vulnerable.’ It was hard to tell people I still didn’t have a job—that I needed help. This felt so personal. I felt so vulnerable that I was scared to do that reaching out, but I reached out to Adam [Sapp, assistant vice president and director of admissions] … He moved his schedule around immediately and had a whole meeting with me about admissions jobs.”

Sapp encouraged Lee to apply for a temporary position as an outside reader for the Admissons Office. He got the job a month later, which helped Lee sustain himself while he searched for a more permanent job and prepared for another round of MFA applications.

“I realized that I am someone who can roll with the punches and land on my feet. I’ve learned so much about myself and my capacity and my work—things I couldn’t have learned in grad school.”

In January, Lee accepted a full-time offer in business development for BlackLine, a cloud software company. He’s also been busy rebuilding his trust in himself after months of uncertainty. With a new set of tools and newfound knowledge of himself, Lee is once again applying to MFA programs that have reopened. He has a final callback in April for the Tisch School of Arts at New York University. Wish him luck.

Zachary Freiman

“The Campaign Staffer Life”

Suddenly last March, Zachary Freiman’s parents saw their brood of three adult sons return unexpectedly to the nest at the family home in Westchester, New York.

On March 11, 2020:

Zachary Freiman, a music and public policy analysis (PPA) double major, had just completed his senior music recital the week before spring break—a capstone event that his father had flown from New York to witness.

Before the arrival of COVID-19, Freiman—a double major in public policy analysis (PPE) and music—was excited to graduate during an election year. He dreamed about working for a big Senate race and living “the campaign staffer life”—where you “uproot everything, and you’re living in the supporter housing, in someone’s guest house eating pizza” while running phone-banks and doing door-to-door canvassing.

When the pandemic began, he was worried and anxious but continued with his academic work, including preparing for his senior music recital, a major capstone for most music majors. “I spent four years at Pomona pretty much running back and forth between Thatcher and Carnegie,” he recalls.

The week before spring break, his father flew in from New York for the recital, and Freiman remembers jokingly asking him to bring cardboard boxes and packing tape in case they needed to pack up his dorm. In the end, his father did help him pack up and get home.

During the next few months, COVID-19 hit the Westchester area hard, with shelves empty of toilet paper and trips to the grocery store fraught with worry. “We were scared and at home,” Freiman recalls. “My dad runs a small business, and that got hit really bad, and he was struggling. My mom was working in politics and was out of a job. We were all basically struggling as much as the country was and is. It was a deeply stressful, traumatic experience to be home during the pandemic with my whole family there, not knowing if it’s airborne, if we can go see our grandma, if we can go to the grocery store—we’d wipe down the bags, wipe each item out of the bag, wipe handles … We were neurotic. We couldn’t find yeast, couldn’t find toilet paper or even cleaning supplies.”

The situation only grew worse as Freiman continued to search for campaign jobs during a unique moment in history. After the initial scramble of campaigns regrouping to move operations to the virtual world of online organizing, Freiman got a notice from a friend that a Democratic campaign of some kind in North Carolina was hiring.

“Who it was for, I wasn’t sure, but I sent in my application,” remembers Freiman with a laugh. “Someone texted me back furiously: ‘We need to hire you.’ So I interviewed with this guy, and I didn’t even understand what this campaign was at first. Turns out, I began working for the Biden campaign in North Carolina.”

The job was virtual, so Freiman was working from home. His duties included helping get campaign volunteers into the virtual space. “We were having to teach the volunteers how to Zoom. We had to spend hours and hours with really lovely, elderly volunteers—volunteers who had been volunteering for years—we had to help them as if we were their grandchildren. I was part of a fleet of young staffers acting as grandchildren—helping them with tech problems. I’ve had to help my grandparents with these things like opening a browser, using Gmail, how to plug in your headphones.”

Freiman was able to travel to North Carolina for the last few weeks leading up to the election to safely canvass neighborhoods and go door-knocking while maintaining social distancing.

Today the campaigns are over, and Freiman has left his family home and moved in with with his former Pomona roommate, William Baird-Smith ’20, in Washington, D.C. He wants to be close to the action as he continues his search for meaningful political work.

Freiman’s experience with the campaign staffer life may not quite have been the post-Pomona adventure he had envisioned, but for now, at least, it was close enough.

Zaira Apolinario Chaplin

“Frazzled, Confused and Lost”

Zaira Apolinario Chaplin recalls returning to her family in New York—the epicenter of the coronavirus at the time—after campus was evacuated last March. She arrived home with a cold. Fearing the worst, she camped out in the living room. Her makeshift bedroom served as a remote classroom, and her suitcases were her closet. “I was super frazzled, confused and lost.”

On March 11, 2020:

Zaira Apolinario Chaplin, an international relations major, had a job offer in hand with Accenture and was planning a fun summer, with a research project and a trip back to Brazil, where she studied abroad.

Her mother, Erminia, worked as a caregiver at the time and had to travel to Florida with the family she worked for, heightening the stress that Zaira was already feeling in those early months of the pandemic.

Fortunately, professors extended a lot of deadlines. Her thesis readers continued to support her, but living through a pandemic while trying to wrap up your final semester of college was difficult. “I was nowhere near as productive as I was in school. But I thought, ‘I have to get it done. I have to graduate. I cannot end on a negative note.”

Not only did she graduate; she was awarded the John Vieg Senior Prize in International Relations for her thesis.

She kicked off her summer by spending quality time with her family. She started learning to crochet; she baked; and she took up gardening with her mother. She kept this up as she started a part-time research gig working for Professor Guillermo Douglass-Jaimes.

An international relations major, Apolinario Chaplin had secured a job as an analyst with Accenture in San Francisco that was slated to start in early fall. As she was finishing up her research work for Douglass-Jaimes, she received an email from Accenture pushing back her start date to January 2021.

“That gave me time to spend time with my partner in her home city of Rio de Janeiro,” says Apolinario Chaplin who remembers multiple canceled flights until she finally booked a flight and made the trip to Brazil, where she tested negative for COVID-19 and booked an Airbnb. “It was nice to have some breathing room, have a little bit of space and also to have my own apartment, naturally. I just cooked a lot and tried so many recipes, I made all kinds of soups and just really spent a lot of time with myself,” she says. “I learned how to box braid my hair and experimented with styling kinky black hair textures like my own. I joined a Facebook group called ‘Safe space for Black girls who never learned to braid,’ and it was really emblematic of the special, online quarantine communities that many people sought out in the early months of the pandemic.”

The time in Rio was a contrast to the past few months in New York, where the only places she could get outdoors were in parks. “Versus in Rio, you can go camping, hiking, and that really changed the way I spent my time, to be able to be in fresh air and not be concerned with contaminating other people.”

Even with the outdoor opportunities, Apolinario Chaplin experienced a side of the pandemic in Rio that she wasn’t used to. “Generally, people weren’t taking the pandemic very seriously. Every single restaurant was open; clubs were open; bars were open; every other person was wearing a mask. People tended to treat the pandemic and the discussions around social distancing as something banal, a minor inconvenience.”

Apolinario Chaplin came home to New York in January. Her mother had quit her caregiver job and was now cooking Brazilian food and selling it via an app called Shef. “It’s been nice to see her entrepreneurial side, and it’s a big relief for me because she doesn’t have to travel with the family anymore.”

Since her start with Accenture, her life has been more of a whirlwind than the relaxed months she spent in Rio. Training was intensive, but she started with a cohort of other new, nervous beginners like herself. Accenture sent her a work computer and a headset, and she now works from home, with a schedule that has been busy but flexible. But Accenture also has a branch in Rio, and the thought of transferring there someday gives Apolinario Chaplin a special goal to work toward in the future.

Miguel Delgado-Garcia

“A Roller Coaster I Was Riding”

During the fall of his senior year, student body president Miguel Delgado-Garcia, was putting in a busy schedule to ensure that he would have a smooth spring semester. A public policy analysis (PPA) major, he had done all the research he needed for his thesis, which he was going to write in the spring. He jumped into the hiring cycle for consulting firms and secured an offer from The Concord Group, a national real estate strategy firm. He was also traveling twice a week into Los Angeles for an internship, all while fulfilling his duties as president of the Associated Students of Pomona College (ASPC).

On March 11, 2020:

Miguel Delgado-Garcia, a public policy analysis (PPA) major and student body president, had already accepted a position with a L.A.-based consulting firm and did not anticipate any changes in the offer.

As spring began, his busy fall seemed to be paying off. In the weeks leading up to the evacuation of campus, Delgado-Garcia had been going out with friends and enjoying his last semester at Pomona. Then: “I was in theatre class when we got the email, and initially, I just felt shock and awe. I saw Dean Ellie Ash-Bala and we’re just sitting together in disbelief when Dean Josh [Eisenberg] came out and said, ‘OK, what are we going to do?’”

From then on, it was all business for Delgado-Garcia, who helped set up a meeting between the ASPC and Pomona’s executive staff, getting it livestreamed and ensuring they asked all the pertinent questions on behalf of the student body. Amidst senior activities and pre-spring break celebration, the student body chose to unify and advocate for each other. “I think that was the beginning, when we had to pivot and acknowledge that we’re in a new world.”

For Delgado-Garcia, that included working with student activist groups to secure housing and funding for students who had to leave campus but didn’t have a viable place to go to on short notice. “That was difficult because I always felt stuck in the middle. I was elected to advocate for the students, but I also understand the struggles the College was facing. It was a constant, nonstop remainder of the semester. I remember calling Professor Eleanor Brown, my thesis reader, and just breaking down. I didn’t have my thesis draft ready. I shared what was happening in ASPC. She helped me calm down. All my professors were supportive. It was definitely a difficult semester. It was a huge transition, and then one day, I submitted my thesis and graduated.”

By this point, Delgado-Garcia had moved back home with his father. “Suddenly I was in my childhood room, where I had applied to Pomona. I hadn’t planned on moving back home after graduation. I thought I was going to move directly to San Francisco, and here I am.”

And then, the week before finals were due, Delgado-Garcia got an email from The Concord Group informing him that they wouldn’t be able to hire him. “At least through the remainder of the semester, I knew I had a plan because I had a job … and then my job was gone. The carpet was pulled out from under me. They informed us that due to the pandemic, and in order to honor their current employees, they wouldn’t be able to bring us on. They had halted all hiring.

“I graduated, and suddenly I was an adult with a college degree, with no job, living at home. It was a span of six weeks after graduation where I slept a lot, read a lot of books, went on a lot of hikes. There wasn’t a lot to do being quarantined in L.A. I applied for a couple of jobs. It really knocked down my morale in general: I had been on a high, a roller coaster I was riding, and it suddenly dipped.”

Luckily for Delgado-Garcia, The Concord Group sent him a second email a few weeks later, re-offering him the position. At that point, he had activated his Claremont Colleges’ network and through a connection, had secured an offer with another consulting firm. Ultimately, however, he went with the original job offer.

In the end, Delgado-Garcia is grateful to have lived through those experiences to grow as a leader and as an individual: “It steeled me.” Because he’s working remotely, Delgado-Garcia is just now starting to feel confident in his job, nearly eight months later. He’s moved out of his father’s house and in with one of his longtime best friends, Nicole Talisay ’20.

He’s thinking about graduate school for the future, but for now, he wants to soak up as much as he can. Eventually, with a master’s in public policy in hand, he’d like to work in the public sector. “I’d love to go get my master’s in two to three years, but I’m not ready to go back [to school] yet. Especially not in a pandemic.”

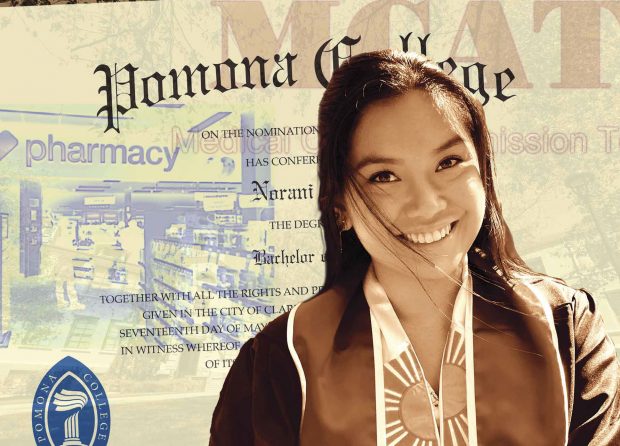

Norani Abilo

“The Uncertainty of the Pandemic”

Norani Abilo had a clear plan for her next two years. She would take the first year off after graduation and apply to medical school the next year. During that two-year gap, she planned to work in a clinical research setting to gain clinical laboratory hours and build strong relationships with health care professionals. All in all, a solid plan, she thought.

On March 11, 2020:

Norani Abilo, a molecular biology major, was in the middle of her job search looking into clinical research jobs—part of her plan to gain precious clinical hours in preparation for medical school, for which she planned to apply the following year.

“I was thinking that I could still apply to jobs outside of California, so I was trying to think about my options,” she recalls. “I hadn’t applied to too many yet when the pandemic hit, and then applications were put on hold, and I was asked to wait longer for decisions. I was starting to stress out and wonder what’s going to happen post-graduation. That’s when I started applying to as many jobs as I could, but no one was really getting back to me.”

In all, she applied for almost 200 different jobs. Some employers did get back to her and even interviewed her before they halted or let her know they were moving on to someone else. It was after some months of this that Abilo applied to a pharmacy technician opening at a local CVS Pharmacy in Encino, California. “It wasn’t part of my original plan,” says Abilo, who is from Los Angeles, but the pandemic has forced many a well-laid plan to go awry.

The position didn’t require certification. CVS trains you on the job, explains Abilo. Working part time since November, Abilo has been able to study for the MCAT and focus on her medical school application materials as she works with Pomona’s Career Development Office through the process.

Back on track for her long-term plan, Abilo is now facing a new hurdle: canceled, postponed and overbooked MCAT testing dates. There are applicants from the last pre-med cycle who weren’t able to take the MCAT because of COVID-19, and they are the ones being prioritized by MCAT testing centers, explains Abilo. “My MCAT keeps getting canceled or pushed back. Right now I have to decide [what to do] because I’ve already submitted to the Pomona Pre-Health Committee, and I have to let them know if I’m applying or not this June. I feel the uncertainty of the pandemic, and not knowing what I’m doing in five years is stressing me out more.”

This stress of the unknown is nothing new to Abilo, who spent her last few months as a Pomona student helping her fellow first-generation and low-income community find housing after the campus was evacuated. Abilo was able to stay with a friend in an apartment near campus but then moved back in with her mother.

Abilo and her mother, a caregiver, live in the Pacoima. They share a converted garage that doesn’t afford much space to either of them. Living with her mother, Abilo held off applying to hospital jobs for fear of contracting COVID-19 and not being able to isolate in their cramped quarters. But now that both have gotten the COVID-19 vaccine, Abilo is considering applying to these jobs—although CVS has proved to be a valuable learning experience.

“Even the pharmacy was pretty scary at first,” she admits of the fear of contracting the virus. Abilo has dealt with customers who refuse to wear a mask, even when standing near elderly, more vulnerable people in line. Other customers are coming in while ill, sometimes just getting over COVID-19. Others are just plain rude.

It’s not all negative though. Abilo is gaining precious clinical experience—and she’s learning a lot from the patients and from the pharmacists. In addition, she’s met some lovely customers. “There are good customers, older folks who don’t have anyone at home. They’re happy to see us, as we’re the only source of interaction they’ve had in weeks.”

2021: Another Year Without Streamers?

Even as Abilo deals with the anxiety of her MCAT being endlessly postponed and her plans potentially laid waste by the pandemic, she’s also thinking sympathetically about the Class of 2021. “Class of 2020 had it rough, and I know Class of 2021 will too.”

As we enter year two of the COVID-19 pandemic and a second academic year that may end without the festive blue-and-white streamers over Marston Quad marking Commencement, the situation will again test the mettle of young Sagehens. Like the class before them, these new Pomona graduates may be taking their graduation photos in their own driveways and front yards. And like their predecessors, they may have to make their way in an economy still struggling toward recovery.

Like the Class of 2020, members of the Class of 2021 have been indelibly marked by the events of the past year, but they also will be able to say, in their turn, that they struggled, coped and eventually found their way in the midst of a global pandemic unlike any other in at least a century.