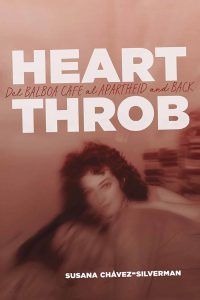

Heartthrob

Del Balboa Cafe al Apartheid and Back

By Susana Chávez-Silverman

University of Wisconsin Press | 336 pages | $34.95

Some say Romance Languages and Literature Professor Susana Chávez Silverman has outdone no less than J.R.R. Tolkien. One author points out that while Tolkien invented a number of languages, Chávez Silverman “has turned Spanglish into an astute literary tongue capable of baroque depths.” The International Latino Book Awards literally seconded that—her book recently won second place in the memoir category.

Chávez Silverman is known for seamlessly alternating languages. But that is style. Even more than that, what she does in her new book, Heartthrob (subtitled Del Balboa Cafe al Apartheid and Back), is storytelling. Using her letters and diary entries as a palimpsest, Chávez Silverman chronicles a love affair that is both deep and delicate, fiery and fragile, set against politics and place—and one that takes her from San Francisco to South Africa.

PCM’s Sneha Abraham chatted with Chávez Silverman via Zoom (or as the professor likes to call it: “Zoomba”) about language, love, location and more. This interview has been condensed and edited for space and clarity.

PCM: Tell me a little bit about your family and how language was used in your household.

Chávez Silverman: Well, that’s a very intriguing question because my current project is actually delving into a bit of my family history, particularly on my mom’s side. And that’s something that I haven’t really written much about—my family.

My dad was a Jewish-American Hispanist born in the Bronx, and my mom was a Chicana. She was born in Visalia in California and grew up in San Diego. They met in summer of 1949. It was kind of like a study abroad experience. My mother got a fellowship from the Del Amo Foundation, I think. They were both on a study program in Spain. That’s where they met.

And each of them had apparently a fairly serious paramour. But when they met, it was like a flechazo, like a love-at-first-sight thing. They got married in 1951, much to the disapproval of my dad’s mother in particular. I have my parents’ love letters, which were sent to me a couple of years ago by my youngest sister. She had inherited them when my mother passed. And there are quite a few.

And my mother’s parents were also not in favor of the union, particularly her father. My mother was the granddaughter of two ministers. Her maternal grandfather was a Presbyterian minister, and her paternal grandfather was a Methodist semi-itinerant preacher. This was in New Mexico. My mother’s parents eventually came around, to the point that my parents’ wedding was on their front lawn, performed by Samuel Van Wagner, my great-grandpa.

We grew up, mainly, English dominant-ish when I was very, very young. However, we were around relatives who spoke different languages. On my dad’s side, it was Yiddish and English. We weren’t too much in connection with my dad’s, but they were all back in New York. But on my mom’s side, we were very, very close to my mom’s parents, to my grandparents, my maternal Chavez grandparents, and they spoke Spanish and English or sometimes code-switched with all my grandmother’s siblings and relatives, etc. We often were there in San Diego with them.

And my dad played with language a lot. My mother did not encourage code-switching, but it has to do with the time that she grew up in, in the ’40s, and the particular prejudice she experienced. It was: You speak correct English or correct Spanish—no mixing! And it was all about assimilation. And my mother retained her Spanish. Her two sisters really did not.

But because my dad was on sabbatical, my first year of school was in Madrid, when I was 4 and 5. I was thrown into a Madrid kindergarten. That was one of my top traumas. I don’t have a lot of memories of my early childhood, but I remember that. That’s a horror because I was very shy, with minimal Spanish at first, and I was terribly bullied at school.

PCM: How does language work in your head? Are your dreams multilingual?

Chávez Silverman: Oh, yeah, very much so. As a matter of fact, dreams form a very crucial foundational kind of intertext. I always think of the Argentine writer Julio Cortázar, who said that many of the subjects of his stories came from dreams. A little grain or a little seed or even a full scene or images come from my dreams. I have a lot of access to my dreams.

I’m a proselytizer for dreams. I tell my students, “How many of you remember your dreams? If you don’t, here’s how to remember them and keep a dream journal, etc.” Because I think it’s very important.

But I dream in both Spanish and English, sometimes Italian, sometimes Afrikaans. And I also dream in languages that I don’t speak. Like, I wake up, and I know I was speaking German, which I don’t—I have a slight understanding, but not much. I don’t speak it.

PCM: When you write letters or crónicas, are you conscious of their potential of being published?

Chávez Silverman: Oh, yeah. Well, let’s see, initially, I wasn’t, as a matter of fact. This whole transformation or process started—I can date it very clearly to 2000, when I had won an NEH Fellowship to Argentina, and I had been living in Buenos Aires for a good part of a year. I would be there a total of 13 months.

And I was writing and emailing. I’ve always been a correspondent. Without my journals, which I recopied as letters, and letters that people returned to me and emails, my recent book, Heartthrob, could not have been written. I started sending these emails home from Argentina. I was meant to be writing a scholarly book on poetry, which I was working on.

But when I got back to the U.S., pretty soon, within a couple of weeks, I think, 9/11 hit. So, this is 2001. And I had a teenage son—he was 14 and started acting out. And I just felt very disoriented between 9/11 and reentry shock of being back after living abroad for a year.

And my editor himself said, “You know what? I can’t think that a book on Argentine poetry is going to be a big hit or a bestseller.” I mean, academic publishing was already starting to struggle. It was 20 years ago.

I had begun to send these—I had deliberately called them crónicas—and send them along with my letters to people. “How many of those do you have?” I said, “I don’t know—20, 30.” He said, “That’s your book.” So it was really Raphael Kadushin, my former editor at University of Wisconsin Press, who identified the work I was doing as publishable writing, as literature.

PCM: Heartthrob is very intimate. How is it to write to the bone?

Chávez Silverman: But I don’t, my darling. I mean, I’m really very glad that it gives that impression. But I actually consider myself to be a rather close-to-the-vest person. However, I know that my writing gives people the impression that I’m spilling my guts.

In my author’s note in Heartthrob, I’m citing the writer Wyatt Mason about Linn Ullmann, who is a Norwegian writer. And he writes, “She was not looking for reportorial evidence, even if she was writing a scene based in what she could recall. She allowed herself to see with the imagination. She gave herself the freedom to imagine what had been forgotten, not in an attempt to establish fact, but to find the truth.”

I thought that was brilliant. That quote kind of gets at that tension that comes out in my epigraph between truth and reality. So I’m very aware. I’m always negotiating when I’m writing—how much to share and how much to leave out.

Publishing and truth, you spilling out your whole guts, they don’t always go together. It’s about a process of negotiation. And I’m very aware of that.

PCM: This book takes you across the world. Can you talk a little bit about place and love and how one impacts the other?

Chávez Silverman: I had the sense—it’s hard for me to know what kind of wisdom comes with hindsight, but it’s a lot, you know. But even at the time, in the ’80s, I ended the relationship, but not because I didn’t love him or he didn’t love me. I was finding the place, South Africa, impossible for me. I was very politicized throughout my 20s, especially. It didn’t stop but it morphed—elements of practicality and motherhood and other things came in.

I don’t want to say I had a death wish, but it was pretty ridiculous to throw myself off that cliff and move to South Africa under apartheid, considering my political beliefs and the family that I grew up in and everything. But I hate that. The heart wants what it wants.

I mean, it was love at first—it was a major flechazo, similar to my parents, ironically. My parents, by the way, met the Roland Fraser character in San Francisco. And both of them liked him. My mother was very fond of him. I’ve just discovered both he and my mother share a moon in Capricorn. Yes. I’m very into astrology as my friends, readers and students all know.

But it’s as if I felt something fundamentally shift between us. I’ve written that he got swallowed by the underworld, the undertow, not exactly of apartheid per se; he was very progressive for a privileged, white English South African at that time. But it wasn’t that. It was between the familial and sort of the societal structures and expectations of the northern suburbs of Joburg. He was the eldest of six, and the family expectations on him, and also his own double Capricorn personality—we were screwed, kind of, by the place, by the effect of the place on us.

And yet, as I also write in the book, it was almost as if upon sacrificing that relationship, which was really my true love, I became myself: a writer. And that’s how I see my writing really. I started thinking of myself as a writer in my mid-20s in South Africa.

We revisited our love story and saw that the feeling is the same, or it’s there still. And yet, for me, it’s still impossible. I don’t want to make a life in South Africa. It’s something that has inherent tensions and impossibilities that make it very powerfully seductive and also impossible. I tried to capture that in the book’s final sentence.

PCM: Love is not enough. Right?

Chávez Silverman: Right.

PCM: With love, there’s an intensity and there’s also a breakability. Does that change over time?

Chávez Silverman: I have a tension between the heart and the head. So you can chalk it up to the stars, or chalk it up to the personality or whatever. Probably the signature word that a lot of people would apply to me would be “freedom.” People have said that I’m very iconoclastic in many ways.

And so, there was some part of me that railed against … I don’t think love, passion and domesticity go together very well, for example. So that wasn’t going to go over well in that South African mundo, which was going over to his parents’ for barbecue for lunch every Sunday and so on.

No. But we didn’t have any way of seeing that ourselves, madly in love in San Francisco, in New Orleans. You know, I couldn’t see that until I actually went there. I’m not at all sorry because, paradoxically, going there to South Africa also made me who I am in many ways. But as far as love, I mean, I can’t tell you anything except this: I have a very romantic heart, and I’m also intractably rebellious or freedom-oriented.