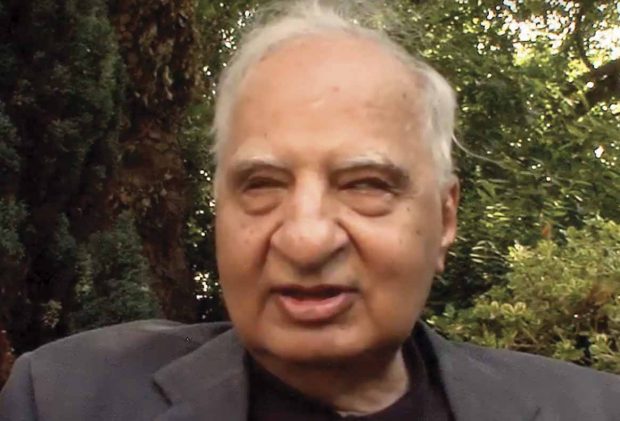

Ved Mehta ’52

Author

1934–2021

Ved Parkash Mehta ’52, noted author, died Jan. 9, 2021, at age 86 from complications of Parkinson’s Disease. Blind from an early age, Mehta is best known for his autobiography, published in installments from 1972 to 2004. Born in India, he lived and worked mainly in the United States, writing for The New Yorker magazine for many years. Here are a few excerpts from the obituaries published around the world following his death:

The New Yorker

“His book The Ledge Between the Streams describes his life as a blind child in the India of the 1940s, as he learned to read Braille and to ride a bicycle and a horse. Throughout his youth and his maturity as a writer, Mehta was determined to apprehend the world around him with maximal accuracy and to describe it as best he could. ‘I felt that blindness was a terrible impediment, and that if only I exerted myself, and did everything my big sisters and big brother did, I could somehow become exactly like them,’ he wrote.

“Mehta came to the United States when he was 15, and attended the Arkansas School for the Blind, in Little Rock. After studying at Pomona College and Oxford University, he began to flourish in his working life as a writer. He asked David Astor, the editor of The Observer, about writing a 14,000-word piece about his travels in India. ‘Something that long and boring,” Astor reportedly said, “only The New Yorker would publish.’”

Mehta joined the staff of the magazine when he was 26 and, for more than three decades, wrote a stream of pieces, many of them appearing in multipart series. He wrote about Oxford dons, theology, Indian politics and many other subjects.”

The Times of London

“So lush was Ved Mehta’s description of visual detail, so painterly his attention to colour, the American author Norman Mailer refused to believe he was blind. Waving his fist in front of Mehta’s face, the famously pugilistic Mailer said: “If you don’t come out and fight with me, you will show yourself to be a coward.”

Mailer’s incredulity, if not his confrontational manner, was understandable; it was indeed hard to understand how Mehta, without his sight, could write such descriptions as this one, from the first installment of Continents of Exile, his 12-volume memoir: “The fields become bright, first with the yellow of mustard flower outlined by the feathery green of sugarcane, and later with maturing stands of wheat, barley and tobacco.”

The New York Times

“… Mehta was widely considered the 20th-century writer most responsible for introducing American readers to India.

“Besides his multivolume memoir, published in book form between 1972 and 2004, his more than two dozen books included volumes of reportage on India, among them Walking the Indian Streets (1960), Portrait of India (1970) and Mahatma Gandhi and His Apostles (1977), as well as explorations of philosophy, theology and linguistics.

“Daddyji was the first installment in what was to become a 12-volume series of autobiographical works, known collectively as ‘Continents of Exile.’

“‘Ved Mehta has established himself as one of the magazine’s most imposing figures,’ The New Yorker’s storied editor William Shawn, who hired him as a staff writer in 1961, told The New York Times in 1982. ‘He writes about serious matters without solemnity, about scholarly matters without pedantry, about abstruse matters without obscurity.’

“The recipient of a MacArthur Foundation ‘genius grant’ in 1982, Mr. Mehta was long praised by critics for his forthright, luminous prose—with its ‘informal elegance, diamond clarity and hypnotic power,’ as The Sunday Herald of Glasgow put it in a 2005 profile.”

The Sunday Herald of Glasgow

“His most enduring work is surely the ‘Continents of Exile’ series, which was written between 1971 and 2005. It began with stories his father used to tell Mehta and his siblings when they were small. Later, the narrative began to gain its own momentum and eventually a distinct design and architecture emerged. Though he took his lead from Proust and Joyce, his approach was different. As in their epics, memory was fundamental but no less so were other sources, such as letters, diaries, personal papers and newspaper articles. The series culminated in The Red Letters, which begins in New York and describes a a disastrous dinner party, at which his father and mother met Shawn for the first time, and then backtracks to the 1930s when his father had an affair with a married woman.

“Periodically, Mehta—who never had a guide dog or used a stick—would ask himself, “How can anyone be expected to read so much about one life?” His answer was that ‘Continents of Exile’ is not the story of one life but of hundreds of lives, with characters coming and going in the manner of a roman fleuve. Thus the past is regained.”