When Susan Beilby Magee ’66 was 6 years old, she posed for a portrait by Kalman Aron, a Holocaust survivor and fine artist who had come to Los Angeles after World War II and was barely eking out a living.

Fifty years later, Aron, a respected portrait and landscape artist, whose com- missioned subjects include Ronald Reagan, Henry Miller and André Previn, would ask Magee to write the story of his life.

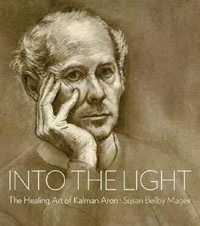

The result, nearly 10 years in the making, is Into the Light: The Healing Art of Kalman Aron, co-published in October by Hard Press Editions and Posterity Press, Inc. in association with Hudson Hills Press. A compelling and graceful mix of first-person memoir, biography and commentary, the book is also a comprehensive retrospective of Aron’s work, encompassing 210 stunning color plates and 30 black-and-white images.

The result, nearly 10 years in the making, is Into the Light: The Healing Art of Kalman Aron, co-published in October by Hard Press Editions and Posterity Press, Inc. in association with Hudson Hills Press. A compelling and graceful mix of first-person memoir, biography and commentary, the book is also a comprehensive retrospective of Aron’s work, encompassing 210 stunning color plates and 30 black-and-white images.

Aron and Magee saw each other only sporadically after her 1951 portrait sitting. Graduating in 1966 from Pomona with a B.A. in international relations, Magee became a leader in the women’s movement in Seattle. She was a White House Fellow, earned her M.B.A. at the Wharton School and held positions in domestic finance and economic development in the U.S. Treas- ury and Commerce departments during the Ford and Carter administrations.

“Pomona College,” Magee says, “gave me the foundation that a liberal arts education is supposed to give you. It was a springboard for me to explore and be curious about life.”

In the mid-1980s, Magee’s life took an unexpected turn. She became a certified hypnotherapist and meditation teacher, founded the Washington Circle of Master Healers and is involved with healing pro- grams at the Center for Prayer and Pilgrimage at the Washington National Cathedral.

Meditation would play a part, too, in Magee’s understanding of Aron’s story and how it informed his art. “If you ask Kalman, ‘Why did you paint that particular painting about that subject?,’ he’ll say, ‘I don’t know.’ His work is unconsciously done.

“Yet you can see in his work that he metabolized his experiences,” she says. “In Kalman’s early work, he was painting all of the desolation and lack of light and color that he saw. That was what was going on in- side him. As he regained texture and color in his life, his paintings exploded with it.

“I sat in silence for five months by myself with 10 groups of his paintings,” Magee says. “What was going on in his life at the time he painted them? What was he working out? What was the influence of the Holocaust? I depended on that quiet listening for the answers.”

It was during a mutual visit with Magee’s ailing mother that Aron asked Magee to write his story. (An interior decorator and art patron, Magee’s mother played a major role in Aron’s early success as a portrait painter. “She sent him all her clients,” Magee explains.)

Aron’s request came after seeing the 2002 film The Pianist. Based on a Jewish-Polish musician’s World War II memoir, the film, Magee says, had somehow given Aron the freedom to tell the story he had tried to forget.

“I wasn’t going to have anybody write it,” 88-year-old Aron says from his home in Los Angeles, “because I didn’t want to remember it.” Magee, he says, “did a good job.”

“I wasn’t going to have anybody write it,” 88-year-old Aron says from his home in Los Angeles, “because I didn’t want to remember it.” Magee, he says, “did a good job.”

After an initial 18 hours of interviews, Magee’s research took her to the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington and to Europe, where she visited the sites of Aron’s childhood home in Riga and the camps where he was incarcerated in Poland, Germany and then-Czechoslovakia. Among the records that she found was the transit paper marking Aron’s arrival at Buchenwald.

From Prague to Salzburg, Magee followed Aron’s post-liberation route as he fled Russian Army custody. She went to Vienna, where the artist and his first wife lived before emigrating to the United States in 1949, and where Aron attended the Vienna Fine Arts Academy on a full scholarship after the war.

At the site of the Rumbula massacre where Aron’s mother was among 25,000 Jewish Latvians killed over two days in 1941, Magee placed a memorial stone honoring both of Aron’s parents.

Aron, who refuses to go back to Latvia, was uneasy about the trip. “I didn’t want her to go,” he says. “It was brave of her.”

Magee, who is not Jewish, believes, however, that she could not have written the book if not for her own “deep healing journey” as a victim of child abuse. “People who know me know the history of what happened to me,” she adds, “but this is the first time that I’ve written it in print.”

For Magee, one of Aron’s most revelatory pieces is a small, dark painting from the early 1950s called “Kalman Marching in the Camp.” In it, Aron is the skeletal central figure, flanked by smaller faces that appear alternately “wise, sad or terrorized.”

“I realized that those were all aspects of Kalman in the camps,” she says. “But the one that survived is the one upfront and center, the one who is utterly determined to survive, even though he has had to let go of most of his light.

“That’s what he would reclaim,” Magee says. “He wanted to live so that he could see the world and paint it.”