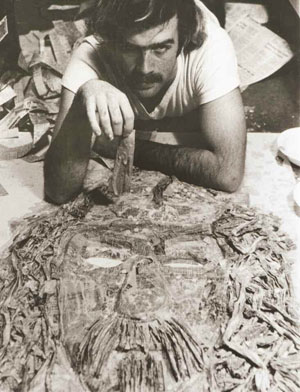

John Irvine ’76 hoists the finished Zappa frieze from atop Bridges Auditorium in 1975.

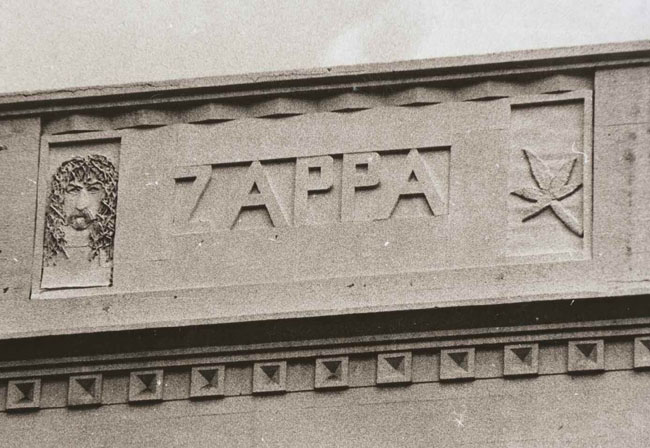

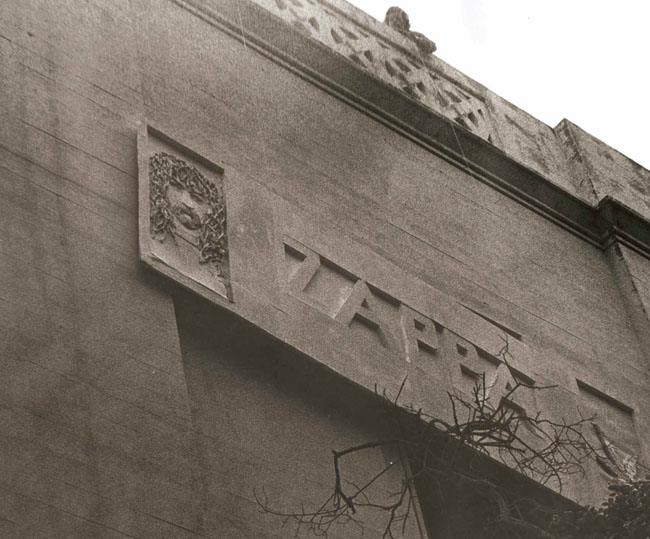

Set in Styrofoam, not stone, Frank Zappa’s name and likeness appeared, seemingly overnight, high upon the face of Bridges Auditorium back in the carefree spring of 1975.

Snugly hung between Wagner and Beethoven, the phony frieze only remained in place for a few days. But the identities of the students who pulled off this high-profile prank—and the tale of how they did it—have stayed under wraps to all but a few Sagehens for nearly four decades. Now the original pranksters finally have come forward with the story of a caper that required a precarious climb, careful calculations and a touch of artistic flair.

Strange as this may seem, it was a Commencement speech given in May by the then-U.S. ambassador to Pakistan that finally shook loose their secret.

Speaking on Marston Quad with Big Bridges looming in the background, Cameron Munter, a veteran diplomat who served in Serbia and Iraq before the Pakistan post, recalled the last time he spoke here, some 40 years ago, as valedictorian of Claremont High School. That led into an anecdote about the epic prank that briefly placed Zappa amongst the iconic composers honored on the front of the auditorium. Munter’s memory, though, was a bit misty—the ambassador just may have had weightier matters on his mind—and he dated the Zappa caper to 1972, crediting high school students “who shall remain nameless” for carrying it out.

Next, Inland Valley Daily Bulletin columnist David Allen dug deeper into the matter, pegging the date to three years later and straightening out a few other details. Still, the notion that the stunt was pulled off by local high-schoolers remained the operative story until a digital dossier laden with black and white photos and a complete account of the caper reached PCM via back channels. The material was pulled together by John Irvine and Greg Johnson, both math majors from Pomona’s class of 1976. After learning of Munter’s speech, the pair decided it was time to spill the beans.

They did it.

Irvine works on the Zappa frieze.

Irvine and Johnson weren’t huge Zappa fans at the time, even though the rocker lived in Claremont for part of his youth. The prank came to mind when Irvine and Johnson learned Zappa was coming to play Bridges in April of 1975. “We were looking up at the front of Big Bridges and said, ‘Well, gosh, he should have his name up there,’” recalls Irvine, who went on to get his Ph.D. and now works at a research laboratory in Cambridge, Mass.

This casual thought launched an intensive, two-week effort. The first big obstacle: How would they scale the imposing auditorium? It was Johnson, another future Ph.D., who figured out that they could get onto the roof of the adjacent old Renwick Gym (long since gone) to extend a ladder across a four-foot gap that separated the two structures, and climb onto the roof of Bridges. “Being young college students, we were stupid enough to do that,” says Irvine of the dangerous move. “I would never do that today.”

Once on the roof of Bridges, they lay down, reached down and measured the dimensions of the frieze, which, they note, was a surprisingly sizeable 15 feet by 5 feet.

Next: Security breach! While they were still atop Bridges, some friends passing by spotted them and asked the guys what they were doing. Irvine and Johnson waved them off, and lucky for them, their rooftop hijinx didn’t draw campus authorities.

The pair had decided it was Chopin whom they would cover up amongst the five composers commemorated on the face of Bridges. “I’m not big on the Romantics,” explains Irvine. “I would never cover up Beethoven or Bach.”

Onward to the design phase: phony frieze would have to be lightweight enough to hoist onto the roof, but sturdy enough to stay in place. Johnson settled on Styrofoam set on an aluminum frame. Irvine, meanwhile got to work on the two end pieces of the frieze, a papier mache bust of Zappa for one end and a marijuana leaf for the other. (The pair has gotten some blowback for the pot image, since Zappa was opposed to drugs. Their response boils down to: “Hey, we know, but it was the ’70s.”) The end pieces were small enough to work on in a dorm room, but to assemble the entire frieze, they set out for the Wash, where they had room to lay everything out.

After a late night that crept into early morning, they were just about done. Then it started to rain on their newly painted masterpiece. They rushed their work of art into the Mudd-Blaisdell trash room. More bad luck: trash pickup arrived that next morning, and Irvine was rousted by an early morning call to retrieve his “art project” which was blocking access to the garbage.

Greg Johnson ’76 makes the dangerous climb from the gym to the roof of Big Bridges.

The guys covered up the frieze and stashed it behind Big Bridges in preparation for the final stage. With the risk of getting caught by Campus Security patrols, the rooftop operation would require some assistance from their friends in the “Statpack,” a group of math and statistics students studying under Professor Donald Bentley. As Johnson and Irvine write in a summary of their caper provided in the dossier given to PCM:

“So, using the expertise in statistical analysis that they were developing under the tutelage of Professor Don Bentley, they modeled the frequency and regularity of the passage of Campus Security in the early hours of the morning. At between 2 and 3 in the morning, the frieze was surreptitiously installed on the front of the building.”

As Johnson recalls it, the Styrofoam had enough give to easily wedge into the notched, recessed space for Chopin’s frieze. They secured the replacement with heavy fishing line tied to various rooftop fixtures just in case it fell—even with the lightweight materials, the frieze’s sheer size meant it weighed 60 to 70 lbs.

Frank Zappa was now shoulder to shoulder with Beethoven and Bach on the campus’s most imposing edifice. Chopin had been shown up, and the two math majors had succeeded in pulling off a highly-visible prank.

The pair climbed down from Bridges, and kept their involvement on the lowdown. They couldn’t resist, however, showing off the stunt to their mentor, Professor Bentley. They got him to take a walk with them, making sure he noticed their handiwork, without explicitly claiming credit. Bentley, to the best of their knowledge, was the only campus official who knew they did it. While the professor didn’t know about the plan in advance, Johnson says Bentley indirectly played a key role in the caper by creating “the camaraderie, the closeness and the culture out of which this whole endeavor arose.”

Campus officials were quick to remove the faux frieze, and the pair never saw their creation again. That helps explain the alternative story from the Commencement speech. Former Ambassador Munter (since hired to teach in Pomona’s International Relations Program) told PCM that he had visited some Claremont High classmates back at the time of the prank, and in the garage of their home was the Zappa frieze. He asked them about it, and they then took the credit for the caper. Irvine and Johnson, meanwhile, largely kept mum over the years, hoping to maintain a mystique around the prank.

And even though the Zappa frieze only stayed up for a few days back in 1975, the Statpack relationships were built to last. “We are friends to this day,” says Johnson.

Postscript: The math guys’ mission did suffer from one miscalculation. Irvine and Johnson didn’t manage to get the phony frieze up until a week after the Zappa concert that had inspired the prank in the first place. “We kind of got an incomplete,” says Johnson. “We weren’t quite ready in time.”