Suffering in silence with no hint or clue to the world, 21-year-old Will Taylor aka “Scooty” died by suicide in March of 2017, just a few months short of graduating from Santa Clara University.

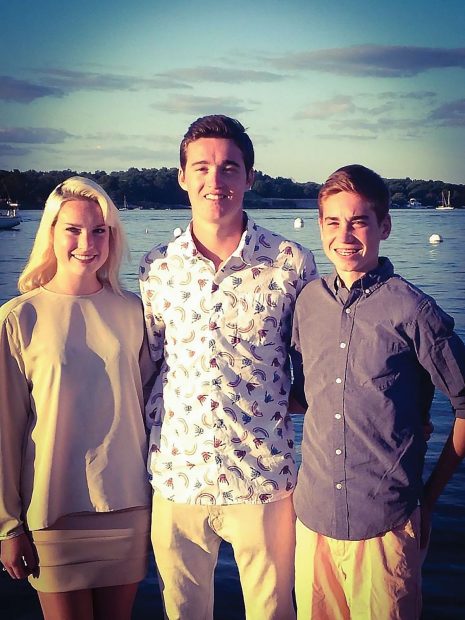

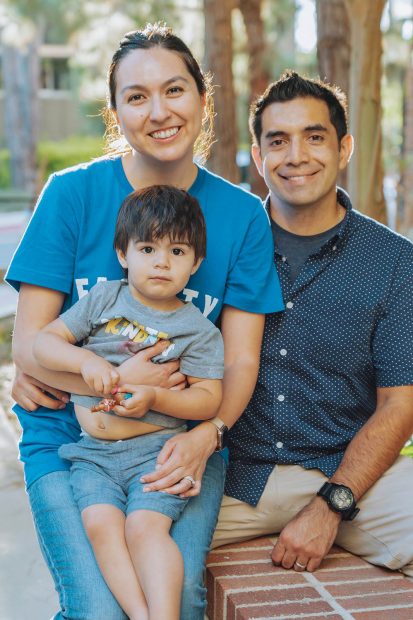

Kasey, Will and Michael Taylor

For big sister Kasey Taylor ’15, the shock and pain were nearly unbearable. His death left her dumbfounded. A two-week leave of absence from her job at a Los Angeles art gallery was not enough time to process his death nor her complex emotions that ranged from grief to abandonment.

“He and I had been so close,” she says. “Even though I know he didn’t choose to leave anyone in his life, it was hard for me not to feel that way—to feel I had been left.”

In the months after her brother’s death, Taylor sought solace and connection with some of her longtime high school friends. Together, they shared their frustrations about the stigma surrounding mental health.

“To be openly honest, since the age of 16 I had been struggling with mental health issues of my own. I had always felt a lot of shame about that, and because of that shame, I didn’t want to talk to other people,” says Taylor. “What I had seen at work with Will’s situation were similar forces. He didn’t share with anyone that he was going through anything, how he was feeling—however he was feeling—I don’t know. His death came as a huge shock to his family and friends.”

If that shame weren’t so present, if Will had spoken to someone, perhaps things might have turned out differently, she can’t help but think.

Born in Santa Monica, Taylor is the oldest of three children. Will came two years later, and soon after the family moved to the Seattle area. Their youngest brother Michael was born when Taylor was 6.

“Growing up, with Will and I being so close in age, we spent a lot of time together,” she says. “We would play at the beach club; we did a lot of Rollerblading with the neighborhood children and during the winter did a lot of skiing.”

As a freshman in high school, Taylor met with some older students who were off to Pomona College and offered nothing but praise for the school, she says. “I knew I wanted to be challenged academically and I didn’t necessarily want to stay in Washington state. I was looking at liberal arts colleges in the sunshine, or where I could ski. When I visited Pomona, the campus blew me away. It was so beautiful and the people I interacted with were friendly, seemed generally upbeat with a laid-back attitude.”

At Pomona, Taylor did some intellectual exploring. Going in as an economics major, she took two econ courses right off the bat—and soon realized they were not a fit for her. She considered sociology and eventually landed in some media studies classes that resonated with her and led her to settle on the major. All the while as she tried on different majors, Taylor continued her minor in art, which served as a baseline to her then and to this day.

Yet even while she thrived academically, Taylor was dealing silently with an eating disorder. After calling Monsour Counseling and Psychological Services (MCAPS), the mental health resource for the seven Claremont Colleges, she was given an appointment with a date that was one week out, not unreasonable for a non-emergency appointment. But by the time her appointment rolled around, Taylor had already talked herself out of going.

Taylor tried once more during her time at Pomona, but the same scenario played out a year later. She got an appointment, but once again lost her resolve. “I told myself I could deal with my mental health issues on my own; I just needed to try harder,” she says.

The impetus to seek help was there, but the moment of willingness to can fade for any number of reasons, including such barriers as health insurance issues, finding an open appointment, or not wanting to be seen entering a building others recognize as a mental healthcare or counseling facility—the exact sort of stigma Taylor wants to erase.

After graduating, Taylor traveled for a few months before settling into her new job as an assistant director at an art gallery in Los Angeles. She’d been working there for more than a year and was living in Santa Monica when on a Saturday morning—March 4, 2017—she received the devastating news about Will.

After sharing her grief and frustrations with her friends, Taylor knew she wanted to do something to honor her brother’s memory. Thinking beyond a one-time fundraiser, she was searching for longer-term impact.

On March 4, 2018, one year after Will died, The Scooty Fund was founded in honor of Will Taylor by his sister and a friend, Tara Nielson. “Scooty,” as Will was called, had been known for his quickness up and down the basketball court during his time at Mercer Island High School.

In the beginning, The Scooty Fund focused on raising money for hands-on crisis resources such as those provided by Didi Hirsch Mental Health Services in Los Angeles, an organization that has operated free programs for suicide prevention, substance use disorders and other mental health issues since the 1940s. The Scooty Fund helped support the center’s training for teachers and administrators to learn how to better help young people going through mental health crises. In less than four years, The Scooty Fund has raised more than $260,000 and has expanded its funding to support research related to suicide among young people, beginning with a two-year University of Washington study that seeks to analyze different personality characteristics and environmental factors to determine their impact on suicide ideation and attempts in adolescence through early adulthood.

Tips for managing Sunday scaries

Be gentle with your self. You’re allowed to rest.

Take five minutes to make a to-do list for Monday.

Schedule something you look forward to during the week

Get outside for 15 minutes or do a physical activity that you enjoy

Remind yourself that the Sunday scaries/blues are normal

Social media has been a big focus from the start to reach The Scooty Fund’s target demographic: young people. Every Wednesday, The Scooty Fund Instagram account is “taken over” by a Wellness Warrior who shares their story about dealing with mental health in an open and transparent manner while also engaging in real-time with followers.

By partnering with other organizations, The Scooty Fund has also led panel presentation events for high school students as well as college and graduate students. Taylor shares her story in hopes that it resonates and connects with others suffering in silence.

“[The goal] is to help young adults better cope with issues, or better support their friends in crisis. To be better equipped to deal with mental health issues when they arise,” says Taylor, whose media studies background from Pomona College gave her the foundation to see how culture plays a huge part in how someone deals—or doesn’t deal—with mental health.

“My upbringing in Seattle included a pretty intense achievement pressure. I’ve spoken to researchers who study this, and it seems that achievement pressure is only increasing for children growing up now,” she says. “Getting into colleges is increasingly competitive and many parents are packing their children’s schedules so they have all the boxes checked. Social media adds to that pressure—we see our peers having ‘great lives’ and we compare that to our own lives and feel lacking.”

There’s no real break, she adds. When someone goes home, they are still inundated in their own rooms and their own spaces, often through social media. A relief from this pressure is imperative, Taylor believes, and she says she senses some movement in the right direction.

“I’ve seen a shift toward speaking about mental health and wellness more often, but the onus is still on the individual who is suffering,” she says. “There’s a lot of verbiage like ‘go to therapy,’ ‘go for a walk.’ I think it’s important for people to engage in their own wellness but when clinical mental health issues are present, we need an emphasis on how [people close to them] can reach out to someone they are concerned about.”

Normalizing these topics of discussion and having more peer-to-peer conversations can create room for people who are struggling to ask for support, explains Taylor. “It creates a space to discuss the topic.”

But how do we change achievement culture? “Through educating people—young adults—about not just taking care of yourself but taking care of their peers and friends,” Taylor says.

The Scooty Fund counts on 30 volunteers to help run things behind the scenes. Both of the co-founders are working full-time jobs and also going to graduate school. Taylor, who lives in Sun Valley, Idaho, is an art advisor for a consulting firm—an interior designer who selects artwork for luxury hospitality projects and corporate buildings—and is working on her master’s degree in marriage and family therapy.

With a full social media team in place, The Scooty Fund’s Instagram account has grown, their Wellness Warrior take-overs are a hit, and the overall feedback is positive:

“Seriously though. Thank you. The page honestly saved me when I was at rock bottom about a month ago. What you started is honestly making such a major impact on so many people whether you see it or not. So thank you.”

With a new podcast, “Scoot with Kasey Taylor,” launched in September 2021, The Scooty Fund is now also sharing expertise from people working in different mental health spaces, including researchers, founders of organizations, journalists, coaches and others.

“I can’t say enough positive things about the volunteers in our organization. They are really the people doing the work, and who are motivated to get these projects completed and out there,” Taylor says. The podcast has been a labor of love for all involved, with a team of eight spending countless hours to produce the first 12 episodes.

More is in the works for the future, including an app for young adults to journal their feelings day by day, with mental health educational content provided as well.

Over the past three years, Taylor has poured many hours into The Scooty Fund. As its president, she has led its growth and with her co-founder, brought together a strong team that is passionate about educating and connecting with young people to destigmatize mental health. Taylor hopes to see The Scooty Fund continue to grow and reach more young people, but she’d also like to take a step back from her leadership role. She plans to focus her energies on building a strong infrastructure that would allow The Scooty Fund to thrive as she shifts careers—she wants to practice therapy and bring mental health discussions into the workplace. The Scooty Fund’s slogan that “together there is a WILL and a WAY” is one she will always take to heart.

Connect with The Scooty Fund

Connect with The Scooty Fund

Instagram: @thescootyfund

Email: hello@scootyfund.org

The Scoot with Kasey Taylor Podcast is available on Apple Podcasts, iHeart Radio, Amazon, Spotify and wherever you listen to podcasts.

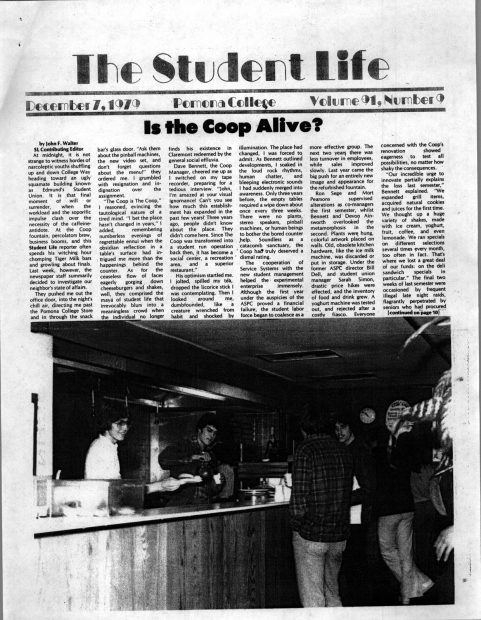

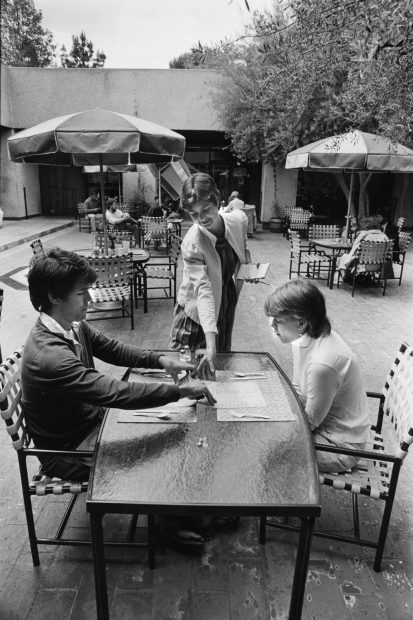

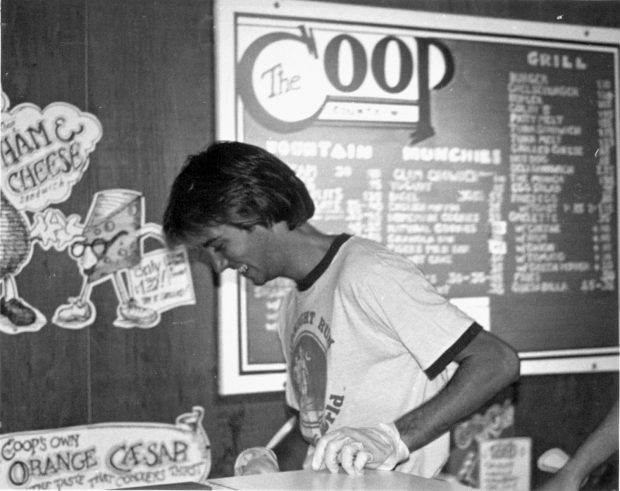

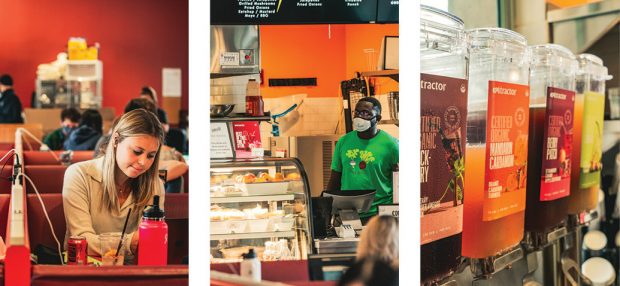

Apparently, those hopes weren’t realized. In 1979, The Student Life published an article with the headline, “Is the Coop Alive?” According to the article, three years prior, “people didn’t know about the place,” “the empty tables required a wipe down about once every three weeks” and it was “soundless as a catacomb sanctuary.”

Apparently, those hopes weren’t realized. In 1979, The Student Life published an article with the headline, “Is the Coop Alive?” According to the article, three years prior, “people didn’t know about the place,” “the empty tables required a wipe down about once every three weeks” and it was “soundless as a catacomb sanctuary.”

1. Grow up in New York City and develop an unexpected appreciation of bugs—and not the computer programming type. “Even as a child, I just loved being outside. I loved turning over rocks,” says Rodriguez, who has a deep affection not only for insects but also for animals and the outdoors.

1. Grow up in New York City and develop an unexpected appreciation of bugs—and not the computer programming type. “Even as a child, I just loved being outside. I loved turning over rocks,” says Rodriguez, who has a deep affection not only for insects but also for animals and the outdoors.

Objects didn’t have to travel physically far—all satellite locations were blocks or buildings away—but that didn’t make the task less daunting. Handling objects at any step of the process is always a risk, says Comba. “There’s always the possibility of human error. We wanted to do this right. We had to take our time.”

Objects didn’t have to travel physically far—all satellite locations were blocks or buildings away—but that didn’t make the task less daunting. Handling objects at any step of the process is always a risk, says Comba. “There’s always the possibility of human error. We wanted to do this right. We had to take our time.” Comba brought on board independent collections manager Karen Hudson, who assumed duties as move coordinator/registrar. “Before you move anything, you need to know what you have,” she says about the time-consuming and labor-intensive process of creating the inventory. “You start by opening up every box, in every storage room and in every building. I had my eye on every single object in the collection.”

Comba brought on board independent collections manager Karen Hudson, who assumed duties as move coordinator/registrar. “Before you move anything, you need to know what you have,” she says about the time-consuming and labor-intensive process of creating the inventory. “You start by opening up every box, in every storage room and in every building. I had my eye on every single object in the collection.” The museum could have hired an expensive professional art-moving company for the entire job, but since the Benton is a teaching museum with a robust internship program, the collection move presented an exceptional chance for hands-on, behind-the-scenes, roll-up-your-sleeves learning. Twelve interns—among them Pomona students Nina Mueller ’19, Ethan Dieck ’22, Jem Stern ’22, Quin Fraley ’22, Katherine Purev ’23 and Emily Petro ’21—stepped up for a challenge that lasted from April 2019 to March 2020.

The museum could have hired an expensive professional art-moving company for the entire job, but since the Benton is a teaching museum with a robust internship program, the collection move presented an exceptional chance for hands-on, behind-the-scenes, roll-up-your-sleeves learning. Twelve interns—among them Pomona students Nina Mueller ’19, Ethan Dieck ’22, Jem Stern ’22, Quin Fraley ’22, Katherine Purev ’23 and Emily Petro ’21—stepped up for a challenge that lasted from April 2019 to March 2020.

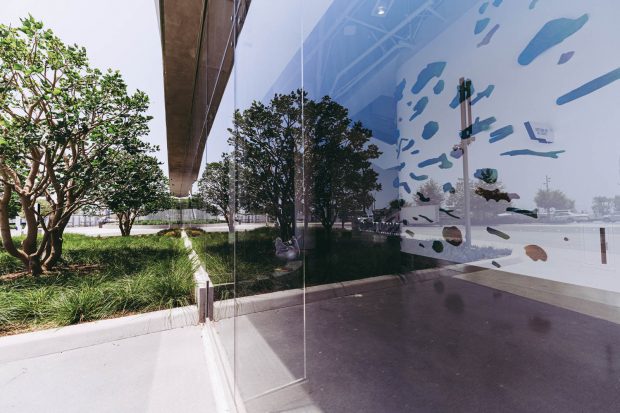

The long-awaited Benton Museum of Art at Pomona College opened to the public in May 2021 with reservation-based visits after the planned 2020 opening was delayed by the pandemic.

The long-awaited Benton Museum of Art at Pomona College opened to the public in May 2021 with reservation-based visits after the planned 2020 opening was delayed by the pandemic.

As an inquisitive girl growing up in the city of Pomona, Genevieve Carpio ’05 learned about her world while riding around town with her family. The adults in her life were happy to converse with their captive passenger, especially one so unusually attentive for her age.

As an inquisitive girl growing up in the city of Pomona, Genevieve Carpio ’05 learned about her world while riding around town with her family. The adults in her life were happy to converse with their captive passenger, especially one so unusually attentive for her age.

In the book, Carpio’s first, she examines the history of the Inland Empire through the lens of mobility—the freedom of movement, granted or denied to various racial groups. She focuses on specific policies used to control not just mass immigration, but also the “everyday mobilities” of marginalized, non-white populations.

In the book, Carpio’s first, she examines the history of the Inland Empire through the lens of mobility—the freedom of movement, granted or denied to various racial groups. She focuses on specific policies used to control not just mass immigration, but also the “everyday mobilities” of marginalized, non-white populations.

“It was so wrong,” Carpio says. “I really wanted to understand what it meant, and why it bothered me so much.”

“It was so wrong,” Carpio says. “I really wanted to understand what it meant, and why it bothered me so much.”

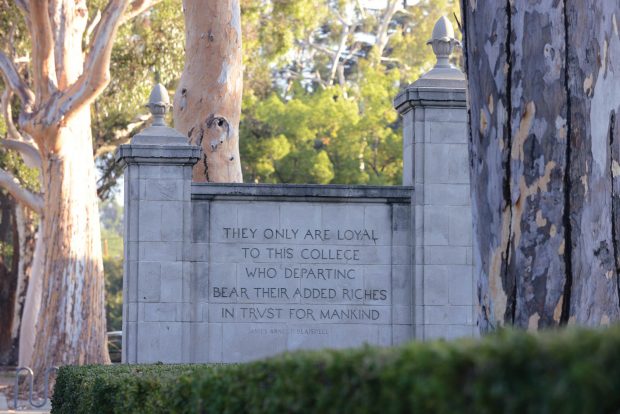

Four years later on her graduation day, Carpio joined her classmates in the traditional passage through the college gates with the weighty inscription: They only are loyal to this college who departing bear their added riches in trust for mankind.

Four years later on her graduation day, Carpio joined her classmates in the traditional passage through the college gates with the weighty inscription: They only are loyal to this college who departing bear their added riches in trust for mankind.

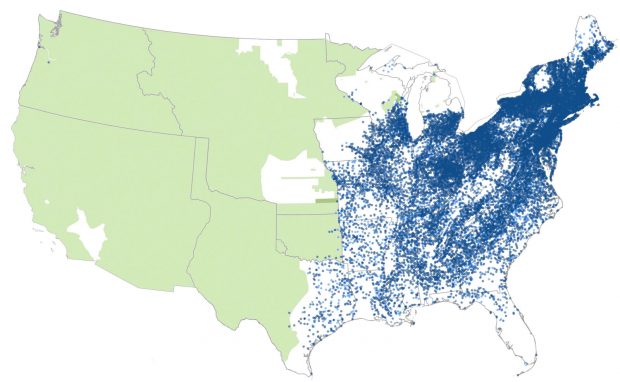

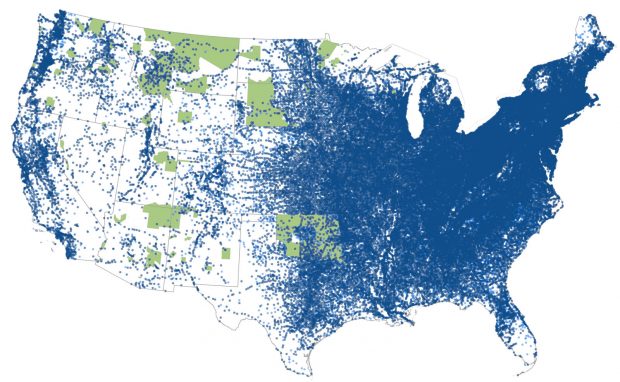

A Wall Street Journal reviewer will go on to call the book “a wonderful example of digital history built on information technology and archival research.” First, though, came the search.

A Wall Street Journal reviewer will go on to call the book “a wonderful example of digital history built on information technology and archival research.” First, though, came the search.

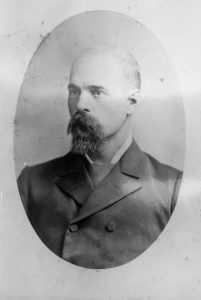

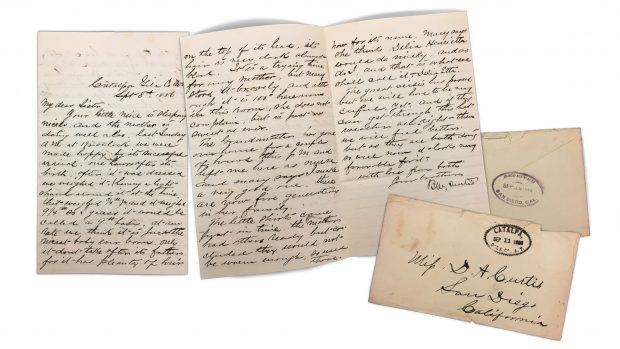

It contained dozens of letters written from the 1850s to the 1890s by Benjamin Curtis and his sisters Sarah, Delia and Jamie. Orphaned in 1852, they had been sent to live with relatives in Massachusetts, Tennessee, Ohio and Illinois. But thanks to the U.S. Post Office, they stayed in touch, especially when they all moved west to equally remote Wyoming, California, Idaho and Arizona.

It contained dozens of letters written from the 1850s to the 1890s by Benjamin Curtis and his sisters Sarah, Delia and Jamie. Orphaned in 1852, they had been sent to live with relatives in Massachusetts, Tennessee, Ohio and Illinois. But thanks to the U.S. Post Office, they stayed in touch, especially when they all moved west to equally remote Wyoming, California, Idaho and Arizona. Lo and behold, in the file Blevins found a photograph of Benjamin, who was far balder than the baby. It was a “humanizing moment” for Blevins as he sifted through the letters offering “beautiful, intimate glimpses” into the siblings’ relationships over decades.

Lo and behold, in the file Blevins found a photograph of Benjamin, who was far balder than the baby. It was a “humanizing moment” for Blevins as he sifted through the letters offering “beautiful, intimate glimpses” into the siblings’ relationships over decades.

“Luminosity, opacity, color, materiality, texture—all are shifting properties of the work that have an innate architectonic rhythm. I strive to make the experience of moving through the space vivid, transformative and impactful. ”

“Luminosity, opacity, color, materiality, texture—all are shifting properties of the work that have an innate architectonic rhythm. I strive to make the experience of moving through the space vivid, transformative and impactful. ”

“Traditionally we think of space housing the work, but in my case the work communes with space—turning corners, echoing shadows, absorbing light and making room simply for what is there. ”

“Traditionally we think of space housing the work, but in my case the work communes with space—turning corners, echoing shadows, absorbing light and making room simply for what is there. ”