Laura Kerber ’06 is a woman with a mission. The bumper sticker on the car in her driveway reads “Moon Diver.” She answers the door wearing a NASA Moon Diver polo shirt. A stack of NASA coasters rests on a table.

Even her marriage has a Moon Diver connection. Her husband of two years is a robotics engineer working on the Moon Diver mission rover. On one of their first dates, they assembled a large Saturn V rocket model using Legos. It’s on prominent display in their living room.

Kerber happily blurs the line between work and play. “It’s kind of like a hobby/job,” she says of her work as a research scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in La Cañada Flintridge, near Los Angeles. Her passion is planetary geology, especially explosive volcanism and extraterrestrial caves. She focuses her attention on Mercury, Mars and, for the past seven years, Earth’s Moon. “I’ve been known to go on vacation and then work on my job,” she admits, cheerfully. “But don’t tell anyone.”

At home, Laura Kerber ’06 keeps a Saturn V model rocket made of Legos.

The proposed Moon Diver mission that she leads as principal investigator began at a picnic table at JPL with a group of five researchers excited about the discovery of caves on the Moon. The Japanese lunar probe SELENE first spotted them in 2009, and the American Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter followed up with high-resolution images. No one has ever explored caves in another world. The scientists began to dream.

One of them, JPL engineer Issa Nesnas, had worked with geologists to develop a rover that could explore hard-to-navigate landscapes. It is basically two wheels with a thick axle in between and looks straight out of Star Wars. When Kerber heard about the vehicle, dubbed the Axel Extreme Terrain Rover, she had an idea. “If I had your robot, I wouldn’t necessarily explore the cave,” she told him. Geologists, unlike engineers, prefer sheer cliffs to flat ground. “I would explore the beautiful cross section of bedrock that’s exposed in the wall of the pit going into the cave.” To Nesnas, it sounded like an intriguing idea, and the two teamed up to write proposals.

- At JPL, research scientist Laura Kerber ’06 poses with a working model of the Axel rover. Courtesy of NASA/JPL-Caltech.

- The Axel Extreme Terrain Rover originally was designed for surface exploration. Courtesy of NASA/JPL-Caltech.

Thus the Moon Diver mission concept was born, through research and imagination. The cave it would explore is in the Sea of Tranquility, the same region of the Moon where Apollo 11 landed in 1969. It is in the Moon’s mare, an area we see as dark swirls on the lunar surface, named with the Italian word for “sea.” The mare (pronounced “mah-ray”), primarily made up of volcanic rock called basalt, was formed by lava flows billions of years ago when the Moon was young.

The near-vertical walls of the cave expose intact strata of the Moon’s secondary crust, which can tell geologists “what was going on ‘inside’ the Moon while the primary crust was forming on the surface,” Kerber says. “Looking at volcanic deposits from deep inside planets using petrology is one of the main ways that we understand the inside structure of planets,” she explains. “The Moon is special because its primary and secondary crusts are both still preserved at the surface, unlike anywhere else in the solar system.” The Moon is bombarded by meteorites, but since it lacks an atmosphere, its surface has not been weathered by wind or water, nor altered, as Earth has been, by the constant motion of tectonic plates. (She likes to tell what she calls a “NASA joke”: “Someone tried to open a restaurant on the moon, but it failed because it just didn’t have any atmosphere.”)

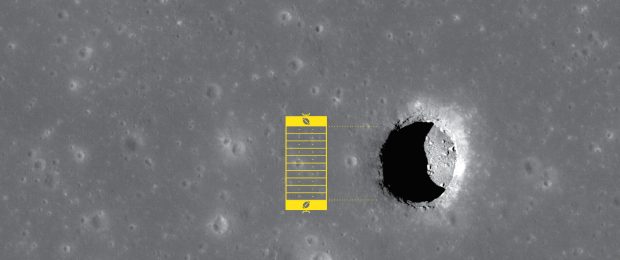

The opening to the lunar pit the Moon Diver mission would explore is roughly 100 meters wide, a little more than the length of a football field, and scientists believe the pit is also around 100 meters deep. Courtesy of NASA/GSFC/ASU.

Tethered to its lander by a cable that supplies power and communications and could extend 300 meters, the Axel vehicle would rappel down the cave wall gathering data as it descended to the floor. Instruments deployed from the rover’s wheel wells would analyze key aspects of the geological record: an X-ray spectrometer for elemental chemistry, a reflectance spectrometer for mineralogy and a camera system to measure the layers of rock.

By 2018, Kerber and Nesnas had persuaded JPL to fund development of the Moon Diver proposal for NASA’s Discovery competition. The space agency funds projects at various cost levels, from flagship class—such as the recent Mars rover Perseverance and the upcoming Europa Clipper voyage—to lower-cost, competitively chosen missions such as Discovery with specific scientific goals for solar system exploration. Kerber and Nesnas directed a team that at one time included as many as 40 people, but the Moon Diver proposal didn’t make the final four in the 2019 funding round.

They ultimately lost out to two missions to explore Venus, “which we thought was fair,” Kerber says, without any apparent hint of jealousy. “Venus is an underappreciated planet. We’ve got to show it some love.”

Not being selected in the most recent funding cycle motivated Kerber and her team to re-evaluate the mission proposal from start to finish. One major area of concern was data analysis. Were they aiming to collect the right data? And would the analytical methods provide sufficiently accurate results to resolve the scientific questions they set out to answer?

One way to find out was to test the methodology on similar basalt flows on Earth. To do that, Kerber reached out to Eric Grosfils, a professor in the geology department at Pomona who was her advisor during her college years. Grosfils, however, is primarily a physics-based volcanologist; Moon Diver needed a geology partner who was chemistry-focused. Grosfils referred Kerber to Nicole Moore, visiting assistant professor of geology. “It was just incredibly serendipitous, because I have studied basalts my entire research career,” says Moore. “First, basalt on a stratovolcano in the Cascades—Mount Baker—for my master’s. And then I studied the Columbia River Flood Basalt for my Ph.D.

“These [Earth] flood basalts are a really good analog for what the Moon basalts might look like,” Moore says. And then she punctures a myth that NASA, in an April Fools’ post, said dates back nearly half a millennium. The Moon, she says, is not made of cheese. “The man on the Moon is basalt.”

In July 2022, JPL’s Laura Kerber ’06, bottom right, took a team of researchers to Washington to test the Axel rover model on basalts that might be similar to those found on the Moon. Nate Wire ’23 at top row, middle, with Pomona Geology Professor Nicole Moore on the top row, third from right.

In mid-July 2022, Kerber, Moore and a team that included Nate Wire ’23, a Moon Diver summer intern, spent a week testing a model of the Axel rover along with various instruments on massive basalt flows in the state of Washington. A major goal was to determine how accurately the instruments proposed for use on the rover in the lunar environment could determine the precise composition of the rocks it encountered.

If the team knew the actual chemistry of the rocks found through highly accurate analytical methods on Earth, says Moore, it could then compare that with results from a handheld device similar to what would be used on the Moon. “We need that precision,” Moore explains. “That was basically the concern of the group that didn’t fund the proposal [right] off the bat. ‘Is this really going to work?’ We’re still actively evaluating the data we got from the field this summer.”

Kerber understands there are no guarantees in the space business. She and her team are working hard to refine the Moon Diver mission proposal for future opportunities. It’s “kind of on this weird journey,” she says. “It might not end up looking like the endeavor that we proposed in 2019. It could morph into something different. It could be something that astronauts could help with in the Artemis program,” she says, referring to NASA’s plans to return astronauts to the Moon. “Or,” she says, “we could repackage it into something a lot smaller. We could fly or hop into the cave.”

Space exploration “is a business of hopes and dreams,” Kerber says. “You have to really love the process, because nothing is guaranteed to happen. You can work a lot on a project and it might never fly.”

So Kerber relishes the journey. “I’ve been having the time of my life working on this project,” she remarks. “Somebody pays me to think about the Moon in a crazy amount of detail. It is such a delight to me. I love working with the team. It’s so fun to work with some of the world’s smartest engineers and roboticists and other scientists that are equally obsessed as I am.”

Given the chance, Kerber would fly to the Moon in a heartbeat. She has applied to become an astronaut twice. One of her colleagues is currently in the astronaut corps. “She’s in space right now,” Kerber says. “She’s poised at the right moment where she could be the first person to return to the Moon. It’s so exciting.”

Laura Kerber ’06, who earned a doctorate in geological sciences at Brown, inspects a specimen in her collection at home.

Kerber is not so sure she’d jump at the chance to go on a Mars mission. “It takes a lot longer to get to Mars, and it’s very, very hard on your body,” she explains. And, with a new baby, she says, “I love the life that I have on Earth.” But the Moon? That would be an easier decision. “Four days away. Go there, have a good time, come back,” she says. If only she had the chance.

Kerber knows her mission may be a long time in the making. “My goal is a long, 50-year goal,” she says. “If I put this out into the universe long enough that somebody will explore a lunar pit, even if it’s not me, then I’ll be delighted to see what the results are. I think that’s an achievable goal.”

The JPL motto is “Dare mighty things.” It fits well, Kerber says, with a quote she loves. “I don’t know where it’s from, but it says, ‘A ship in harbor is safe. But that’s not what ships are built for.’”

“Are you doing something bold and brave?” she is asked. “I try,” she replies. “I fail a lot. I don’t stop trying. Don’t worry so much about all the things that you have to have in place before you start succeeding. Just try and do something hard, and then all those things will take care of themselves.”