A middle-aged Cuban sat at an outdoor table in an alley across from a Havana restaurant that our group would soon enter. Wearing a red and blue baseball shirt, he smiled faintly, and I thought, “Not another panhandler in this impoverished but on-the-way-up nation.”

As I would soon learn, however, this was no panhandler, but a former athlete, one of a number of Cubans of all ages chosen by tour planners to put a human face on today’s Cuba. Rey Vicente Anglada dined with us that afternoon, and then, through an interpreter, highlighted his career as a player and manager for the Industriales and the Cuban national baseball team.

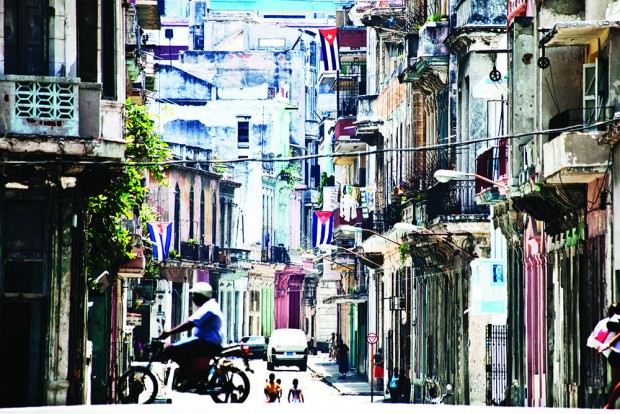

We were 24 Americans visiting Cuba for 10 days. Although at this writing, individual visits by American tourists remain illegal, the recent thaw in relations with Cuba has opened the door to people-to-people (“P2P”) programs like ours, this one operated by smarTours of New York. For my part, I was here to satisfy my own curiosity about the intertwining histories of our two countries, to find out for myself how this Caribbean communist state worked or didn’t, and to meet the island’s people.

The cultural exchanges turned out to be mostly one-sided, but we talked to countless Cubans in all lines of work—artists, teachers, students, cowboys, musicians, actors, guides, fishermen, restaurant owners and one former baseball player.

The first person we met, and in many ways the most interesting, was our 43-year old national guide, Enedis Tamayo Traba. Accompanying us throughout the tour, she put her own spin on both Cuba’s achievements and its failures. A married mother of two, she modestly declared at the outset: “Welcome to my humble country. It is not perfect.” Another time, she noted: “Under Batista, we were mostly poor. Fidel gave us food, housing and health care, which is why we love him.” And in what might have been a popular joke during the Soviet-influenced era, she offered this explanation for the fact that few Cubans are overweight: “The elevators don’t work.”

The tour put us up in a series of luxury properties in Havana (the Melia Cohiba) and Guardalavaca (Playa Pesquaro) near Holguin and at modest but comfortable hotels in Cienfuegos and Camaguey. However, as we toured, there were frequent reminders of the nation’s poverty. Once, Enedis took us to visit a cheerless government store where a farmer had lined up with his rationing book to claim his meager allowance of rice.

However, we also caught frequent glimpses of burgeoning free enterprise—rooms for rent in private dwellings, roadside fruit stands and elderly vendors hawking tiny roasted peanuts to supplement their incomes. In Camaguey, two budding entrepreneurs set up a makeshift display to sell shoes, and puppeteers put on a professional show in a makeshift theatre where seating consisted of about 20 folding chairs.

And then, there are the paladares—homes converted into surprisingly good restaurants. In a country that rations rice, cooking oil, milk and other staples, tourists dine in these privately owned restaurants on shrimp, lobster, crab and fish. At the retro art-decorated La California in Havana, a family-style dinner included pumpkin soup, rolls, black beans and rice, lobster tails, red snapper with vegetables and ropa vieja, a classic dish of shredded beef and spices.

On our final day in Havana, we entered the Partagas Cigar Factory, divided between experienced workers and trainees in hot, humid rooms. Our factory guide, Augustin, related how tobacco leaves are selected for different cigars. By Cuban standards, rolling cigars is a relatively well-paid job, and one that is eagerly sought. Two Romeo and Juliet cigars packed in metal tubes, a gift for a friend, cost me $6.95 each, about 20 percent of the average Cuban’s monthly wage.

Wherever we went in Cuba, we found the artistic muse alive and well. We visited five galleries of different creative pursuits, including the manic display of ceramic art of Jose Fuster in Havana and the feminist art at the Martha Jimenez Gallery in Camaguey.

Musicians entertained us endlessly at concerts and restaurants. At dinner one night in Camaguey, a young man played a trumpet as a woman danced to Latin music near our tables. The musician used a mute to soften the sound against a background of recorded music on a CD, and his partner made her hip-moves while waitresses dodged around her to serve the meal. After one tune, I asked him if he had just played a John Coltrane piece, “Straight, No Chaser.” He quickly answered, “Night in Tunisia … Dizzy Gillespie.”

And of course, any account of a visit to Cuba would be incomplete without some mention of those amazing vintage American cars, visible on postcards, placemats and paintings as well as in the streets. Without them, Cuba simply wouldn’t be Cuba. At different times, drivers chauffeured members of our group in a 1940 Chevrolet sedan and a 1958 Edsel convertible, both impeccably maintained in spite of the seemingly insurmountable obstacle of the U.S. embargo. A 1954 Studebaker parked at a roadside gasoline station could undoubtedly win top prize in a restored vehicle competition in the States.

This tour didn’t come cheap, but we met Cubans and toured their country in ways that I couldn’t have done on my own—even if it were legal.

For those interested in taking part in a people-to-people visit to Cuba, it’s important to keep in mind that (in the words of a customer service representative at smarTours) “it’s not like going to the Jersey shore for a weekend.”

The required paperwork is extensive, including a registration form and a copy of your passport page for the tour company, a Treasury Department travel affidavit confirming that you’re participating in a people-to-people visit; a reservation form for Cuba Travel Services; a visa application; and a variety of health forms.

Here are a few other things to keep in mind:

- Credit cards aren’t accepted and ATMs aren’t available, so be sure to bring extra cash for emergencies.

- Cuba charges a 13% fee to exchange American dollars into Cuban convertible pesos (known as CUCs) but no fee to exchange Canadian dollars or Euros into the national currency, so you can save money by converting your travel money into Canadian bills before you leave

- Photography is prohibited at Cuban airports and military facilities.

- The Treasury Department mandates that P2P tourists keep a daily travel journal and keep it for five years, in order to prove that the trip was legal.