One drizzly afternoon in July, Abe Burmeister ’97 stood in a makeshift fitting room at the Brooklyn headquarters of Outlier, the apparel company he co-founded four years ago, holding a pair of Three Way Shorts in his hands.

Meant for summertime use as both active and leisure wear—“Run, swim or just straight up look good. Our Three Way Shorts can do all three,” reads the online marketing copy—the shorts were the second item that Burmeister and his partner, Tyler Clemens, designed when they formed the company. (The first was a pair of trousers that were meant to look like business- casual slacks but behave like cycling pants.)

The pair that Burmeister handed me, and which I intended to field test, were brick red. They were size 32. And they sold for $135—more than I had paid for my last suit. More, in fact, than I would consider spending on almost any item of clothing, given my penny-pinching ways.

“I’ll take good care of them,” I said, suddenly intimidated by the cash value of the merchandise I’d just received.

“No,” said Burmeister. “You should beat the hell out of them.”

Burmeister’s response might lack the poetic concision of his company’s motto (“tailored performance”) or the high-mindedness of its official philosophy (“we want to build the future of clothing”). But it gets at the essence of what Outlier does: construct hip, all-purpose clothing from the kind of high-tech fabrics normally reserved for outdoor apparel and sportswear.

In response to Burmeister’s injunction, I wore my new Three Way Shorts on a series of summer adventures, bicycling through the mean streets of NYC and swimming, sans undergarments, in the occasionally toxic waters of Lake Michigan while staying with my wife’s parents in Chicago. And while I hesitate to use underworld metaphors when describing a visit to my in-laws, I feel confident that, short of falling off a mountain or diving off a cliff, I gave those shorts as much of a workout as they’ll ever receive.

More of one, than perhaps even Burmeister had in mind when he first toyed with the idea of starting a clothing business back in the early aughts. At the time, Burmeister was partner in an animation studio in San Francisco, and spent much of his time flying back and forth between California and his native New York. Living out of a carry-on bag, he came to wonder if there might be money in making better clothes for business travelers.

That particular idea went nowhere. But several years later, after joining the ranks of New York City’s bicycle commuters, Burmeister was once again drawn to the needle trade. Crossing the Williamsburg Bridge between Brooklyn and Manhattan by bike on a regular basis, he became frustrated by his inability to buy a pair of pants that would hold up to the abuse of hard cycling and inclement weather while looking nice enough to wear into a meeting. So he decided to create them himself.

A trip to the Fashion Center Information Kiosk at the corner of Seventh Avenue and 39th Street—essentially a fashion industry help desk with an enormous button sculpture positioned on top—yielded a list of factories in the garment district. And so it was that, with the help of a local patternmaker, Burmeister made his first pair of slacks using a durable, water repellent, stretchy material from Schoeller, a Swiss textile mill that produces a line of what garmentologists refer to as technical fabrics.

After wearing the pants for a year, Burmeister decided that he could use another pair. He also decided that it was time to start making more than one at a time.

Burmeister’s resume already was impressive in its variety: An anthropology major at Pomona, he worked briefly on the bond floor at Morgan Stanley; ran the aforementioned animation studio and web design firm; acquired a masters degree from the Interactive Telecommunications Program at NYU; toiled as a freelance graphic designer; and developed data visualization tools for a Wall Street firm run by a couple of nuclear physicists. Along the way, he wrote a book, Economies of Design and Other Adventures in Nomad Economics, that explored alternative approaches to the “dismal science.”

Still, Burmeister knew he would need help jump-starting an apparel company.

Then one day, the barista at his neighborhood coffee shop introduced him to Clemens, a fellow urban cyclist who worked at a men’s shirt company and who was, in his spare time, trying to do for shirts what Burmeister was trying to do for pants. Within months, the two had founded Outlier.

(In statistics, an outlier is a data point that lies beyond the norm; the company logo, a black swan inside a black ring, alludes to the rare but catastrophic “black swan events” that roil financial markets. But the term was also once applied to those who lived in outlying regions, apart from their places of work: “the original commuters,” as Burmeister says.)

Burmeister and Clemens initially set up shop in Clemens’ living room. They have since moved into a former wedding dress studio on the third floor of an old Brooklyn sewing factory; a pile of bicycles belonging to Outlier staff lies just outside the door, paying silent homage to the company’s roots.

Their offices comprise an open workspace limned by Apple computers; a small development room crammed with sewing machines, fabric swatches and a rack of reference garments (a Burberry trench coat, an early Gore-Tex jacket); and the fitting room where I tried on my shorts. Outlier’s public face, though, is almost entirely virtual, and the firm uses social media to reach the young, active urbanites who represent its target market.

The partners now employ a professional designer who previously worked at the upscale menswear company Thom Browne, and they have expanded their offerings to include a variety of pants, shorts, shirts and accessories. They continue, however, to seek the same grail: to produce clothing that acts like rugged outdoor gear but looks (and feels) like premium lifestyle apparel.

“They have a nice little niche, which I think will prove to be a very good business for them,” says David Parkes, a tex- tile developer and marketer whose New Jersey-based firm, Concept III, does business with Outlier.

Burmeister and Clemens are forever looking for technical fabrics that might be adapted to other uses, whether that means attending events like the biannual Outdoor Retailer tradeshow, which attracts major outdoor brands like Patagonia and Timberland, or investigating the materials used to make protective clothing for firefighters.

They have cultivated relationships with contract cutting and sewing factories in Manhattan’s garment district, giving them access to skilled workers who are willing to learn how to handle difficult materials.

And they have kept their sticker prices relatively low by selling almost exclusively online through their own website, thereby eliminating the traditional retailer’s mark-up that would miraculously transform my $135 pair of shorts into a $270 pair without improving them in any way.

“Our stuff is certainly not cheap, but it’s half the price it would be otherwise,” says Burmeister, who likens that particular achievement to going from an “incredibly niche price point” to a “semi-niche price point.”

Burmeister and Clemens have reached that point even though their business model diverges from the industry standard. Outlier does not follow the typical seasonal model. Instead, the pair experiment constantly with new designs. “It’s a very development-intensive process. Everything goes through multiple iterations,” Burmeister says.

That costs money: after testing an item in-house, Burmeister and Clemens typically produce a small run for initial release, like a bespoke beta version. “It’s more expensive to make a small amount like that, but it’s worth it to figure out if an item is successful. You don’t get the full range of feedback until you have customers in the wild putting it through all kinds of crazy situations,” says Burmeister.

EAGER TO OBLIGE, and initially skeptical about the technical specs of the clothing I’d been handed, I wore my Three Way Shorts for five days before washing them, bicycling through the steamy summer streets of Queens and subjecting them to the kind of abuse that only animals and small children can dole out: Within hours, my 3-year-old had turned them into a napkin, wiping the remains of dinner (steak marinated in red wine) off his face and onto my lap. Yet Schoeller’s Nanosphere finish, which binds to individual fibers and repels water, dirt and oil, kept them surprisingly clean.

Testing began in earnest the following week, when I lived in the shorts during the two-day drive from New York to Chicago; drenched them in sweat along the bike paths of Illinois and Wisconsin during a scorching Midwestern drought; and finally rinsed them off by diving into Lake Michigan just days after the authorities had posted a swim advisory due to the troublingly high E. coli count.

The internal drawstring—a second-iteration feature that replaced an earlier, and less effective, set of pull-tabs—kept me from accidentally mooning the attractive young female lifeguard, a face-saving feature that was probably worth a few bucks in and of itself. And as I waded back out onto the beach, the lake water drained rapidly from the mesh in the flow-through pockets. When I mounted my bike a few minutes later, the shorts were still moist, but they were already dry enough for me to cycle home without any awkward squishiness.

And marketing hype aside, the nylon-polyester-elastane blend did indeed prove to be both stretchy and durable. Just as important, the double-weave technique employed during milling pushed the tough, Cordura-grade nylon towards the outer surface while keeping the softer polyester threads on the inside. That comfortable inner surface also had a waffle-like texture that Burmeister claimed would prevent the fabric from sticking to my skin, rendering it more breathable and al- lowing moisture to escape.

I won’t argue with him, any more than I will argue with the steady stream of compliments I received on the appearance of the garment. Indeed, after a month of steady use, the shorts had become my go-to clothes—the ones that I found myself slipping into almost every morning. The $135 price tag still triggered my cheapskate reflex, but I don’t exactly belong to the company’s target demographic (i.e., people who have money and are willing to spend it). And as Mary Ann Ferro of the Fashion Institute of Technology pointed out, any fabric that repels dirt and therefore requires less laundering should save water and electricity in the long run. “So maybe,” she ventured, “it’s not so expensive when you think about it.”

Maybe. Maybe not. But even if I might still balk at buying a pair with my own money, I have come to appreciate the advantages of clothing that looks good, feels good—and is literally tougher than dirt.

BEHIND THE PRICE

Performance wear—a category that includes everything from bike shorts to mountaineering pants—is one of the fastest growing sectors in the textile industry. According to a 2011 report by the market research firm Global Industry Analysts, the worldwide market for sports and fitness clothing will exceed $126 billion by 2015.

That growth is helping to drive the development of technical fabrics that have been engineered to possess magical properties: some stretch, others repel water, a few can even kill the germs that make your sweatpants smell not-so-fresh after a workout.

Originating in the first water-repellant fabrics of the 19th century, today’s technical fabrics include synthetics like the finely spun polyester called microfiber; natural materials such as cotton and wool that have been treated with special finishes; and complex concoctions that incorporate a bit of this and a dash of that—perhaps a nylon-cotton blend for durability and comfort, with a bit of polyurethane-based elastane added for stretch and a water-repellent finish to protect against the rain.

Yet adapting technical fabrics designed for spe- cific performance contexts to more fashionable ends can be tricky. The people who design and assem- ble men’s and women’s wear are often unfamiliar with the materials, which do not behave like ordi- nary ones. “It takes skill to sew stretch fabric,” notes Mary Ann Ferro, an assistant professor at the Fash- ion Institute of Technology who formerly designed outdoor wear for London Fog.

And the fabrics themselves—often synthetic, often treated with special finishes—can be shiny, or noisy, or otherwise ill suited to places of work or leisure. “You don’t want to be that guy swishing through the office,” says Outlier’s Abe Burmeister ’97, musing on the loud crinkliness of nylon.

Finally, all of that performance comes at a cost. “The price,” Ferro says, “is a problem.”

Burmeister agrees. Fabric alone accounts for ap- proximately 60 percent of the expenditure involved in manufacturing a pair of Three Way Shorts—a figure that includes the 25 percent bump accruing from tariffs and shipping fees. (Most fabrics used in American garments, including ones that are assembled here in the United States, are made abroad.)

“The materials that The Gap uses cost nothing compared to what we use,” he says.

Jordan Bryant ’13 grew up playing on the competitive club soccer circuit, taking van rides all over Southern California for weekend tournaments, and shuttling back and forth to practices in Orange County every afternoon. By the time she reached Claremont High School she harbored hopes of playing Division I. It had always been her dream, in fact, to play for USC.

Jordan Bryant ’13 grew up playing on the competitive club soccer circuit, taking van rides all over Southern California for weekend tournaments, and shuttling back and forth to practices in Orange County every afternoon. By the time she reached Claremont High School she harbored hopes of playing Division I. It had always been her dream, in fact, to play for USC. When Karen Gerstenberger ’81 holds a quilt in her hands, she sees more than red and purple and blue and more than crisscross lines of thread. She sees the patterns that grief can make on the lives of patients and families. She imagines a young face, cradling the blanket they may receive on their first day of cancer treatment at a Seattle hospital.

When Karen Gerstenberger ’81 holds a quilt in her hands, she sees more than red and purple and blue and more than crisscross lines of thread. She sees the patterns that grief can make on the lives of patients and families. She imagines a young face, cradling the blanket they may receive on their first day of cancer treatment at a Seattle hospital.

Is there any reason for today’s academic institutions to encourage the pursuit of answers to seemingly frivolous questions? The opinionated business leader who does not give a darn about your typical liberal arts classes “because they do not prepare today’s students for tomorrow’s work force” might snicker knowingly here: Have you seen some of the ridiculous titles of the courses offered by the English/literature/history/(fill in the blank) studies department at the University of So-And-So? Why should any student take “Basket-weaving in the Andes during the Peloponnesian Wars”? What would anyone gain from such an experience?

Is there any reason for today’s academic institutions to encourage the pursuit of answers to seemingly frivolous questions? The opinionated business leader who does not give a darn about your typical liberal arts classes “because they do not prepare today’s students for tomorrow’s work force” might snicker knowingly here: Have you seen some of the ridiculous titles of the courses offered by the English/literature/history/(fill in the blank) studies department at the University of So-And-So? Why should any student take “Basket-weaving in the Andes during the Peloponnesian Wars”? What would anyone gain from such an experience? Mahalia Prater-Fahey ’15 knew that she was going to be returning home to San Diego at the end of the spring semester. Thanks to her own timely goal, she got to bring her whole team with her too. Prater-Fahey scored the game-winning goal in triple-overtime as the Sagehens earned the SCIAC championship with a 12-11 win over Redlands, earning a bid to the NCAA Tournament, hosted by San Diego State.

Mahalia Prater-Fahey ’15 knew that she was going to be returning home to San Diego at the end of the spring semester. Thanks to her own timely goal, she got to bring her whole team with her too. Prater-Fahey scored the game-winning goal in triple-overtime as the Sagehens earned the SCIAC championship with a 12-11 win over Redlands, earning a bid to the NCAA Tournament, hosted by San Diego State.

Conceived in 1937 at the College’s 50th anniversary, the house is a two-thirds scale look-alike of Ayer Cottage in the city of Pomona, where the College held its first classes in the spring of 1887.

Conceived in 1937 at the College’s 50th anniversary, the house is a two-thirds scale look-alike of Ayer Cottage in the city of Pomona, where the College held its first classes in the spring of 1887.

During his Pomona College days, Dan Hickstein ’06 landed a prestigious

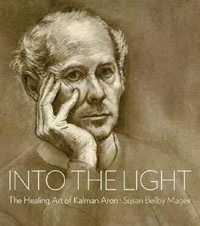

During his Pomona College days, Dan Hickstein ’06 landed a prestigious  The result, nearly 10 years in the making, is Into the Light: The Healing Art of Kalman Aron, co-published in October by Hard Press Editions and Posterity Press, Inc. in association with Hudson Hills Press. A compelling and graceful mix of first-person memoir, biography and commentary, the book is also a comprehensive retrospective of Aron’s work, encompassing 210 stunning color plates and 30 black-and-white images.

The result, nearly 10 years in the making, is Into the Light: The Healing Art of Kalman Aron, co-published in October by Hard Press Editions and Posterity Press, Inc. in association with Hudson Hills Press. A compelling and graceful mix of first-person memoir, biography and commentary, the book is also a comprehensive retrospective of Aron’s work, encompassing 210 stunning color plates and 30 black-and-white images. “I wasn’t going to have anybody write it,” 88-year-old Aron says from his home in Los Angeles, “because I didn’t want to remember it.” Magee, he says, “did a good job.”

“I wasn’t going to have anybody write it,” 88-year-old Aron says from his home in Los Angeles, “because I didn’t want to remember it.” Magee, he says, “did a good job.” On the first day of his Critical Inquiry class, Linguistics and Cognitive Science Professor Michael Diercks strolled into the room, looking very much like any other college student, wearing a plain T-shirt and a pair of jeans. He sat down among his students and introduced himself as Michael. After engaging in conversation with his “classmates” about how late the professor was, he finally introduced himself to the class as their teacher. An awkward silence fol- lowed. And then some nervous laughter. What did they expect? This was a class on social awkwardness!

On the first day of his Critical Inquiry class, Linguistics and Cognitive Science Professor Michael Diercks strolled into the room, looking very much like any other college student, wearing a plain T-shirt and a pair of jeans. He sat down among his students and introduced himself as Michael. After engaging in conversation with his “classmates” about how late the professor was, he finally introduced himself to the class as their teacher. An awkward silence fol- lowed. And then some nervous laughter. What did they expect? This was a class on social awkwardness!