When someone asks me, “So, what do you do for a living?” I have to make a decision. I am triple board-certified in pediatrics, pediatric emergency medicine and adolescent medicine. Do I add “abortion provider” to my list of jobs, or leave it out?

I base my answer on how it might affect me, my family and my patients. Will my family be harassed? Will they be safe? Am I abandoning my patients if I don’t talk about an essential health care procedure that many physicians refuse to perform themselves or to refer for?

I’ve come to believe that talking about my abortion work normalizes it as part of health care and puts a face on a group of medical professionals who are often demonized. Creating that human connection makes this work safer for all of us as providers and patients. But it saddens me that I still ask myself: What are the risks and benefits of talking about abortion? Unfortunately, this won’t change until we stop politicizing health care and start advocating for abortion alongside other social justice causes such as racial equity, fair wages, transgender rights, Indigenous people’s rights and even climate change advocacy, with the understanding that they are all interconnected.

It has been a lifelong journey for me to get to the point where, despite the fear, discomfort and unknown, I (usually) advocate for and talk about abortion.

My interest in reproductive health care started at Pomona with a job I found through the Career Development Office. Despite being a Japanese American teenager who had never discussed sex growing up, I was hired to teach comprehensive sexual education at area high schools. This made me somewhat of an Asian Dr. Ruth, and I became a distributor of condoms and advice regarding birth control, safe sex and consent, not only for high school students but for my fellow Sagehens too. It turns out comprehensive sex ed is something most adolescents desire regardless of ZIP code, family income or education.

The next year, I taught career development classes to pregnant and parenting high school students in Redlands, California, and accompanied pregnant teens to Lamaze classes. I shared in their shock as we watched a video on how babies are born. I also learned to provide pregnancy options counseling through a summer job. And when a friend called me to tell me about her unplanned pregnancy, I was able to support her, without judgment, in her decision-making process. She went on to raise two amazing daughters with the support of her family, friends, church and university.

My interest in social justice grew while I was at Pomona, but it was rooted in experiences I had growing up as one of the few Asian kids at my public school in Arizona. I watched as my non-English speaking parents worked hard to create a life for me and my brother. My father taught karate and built a community in a place where people of Japanese descent had been forcibly relocated during World War II only two decades earlier. Like my father, I experienced racist comments from teachers and students alike. But I also made lifelong friends who showed me inclusivity and friendship. Those experiences led me to help start a refugee youth council in high school to support Hmong classmates who had been evacuated and relocated at the end of the Vietnam War.

In 1992, my parents dropped me off at Pomona. I majored in Asian studies figuring that because I was pre-med, college would be the last opportunity to study liberal arts. Professors Sam Yamashita, Lynne Miyake and Kyoko Kurita, in addition to countless others, taught me how to think critically and build arguments with solid foundations based on reason, compassion and truth. Pomona nurtured students’ intellectual curiosity, developed problem-solving skills and gave us confidence that we could tackle difficult issues.

After college, my work and medical training took me across the country, from California and Arizona to New York, Boston and Atlanta. I’ve been exposed to the harsh reality of health care in the United States: The quality and extent of health care that people can access is almost entirely dependent on their ZIP code, income and identities.

I moved to San Francisco after graduating for an internship at the UC San Francisco AIDS Health Project, where I provided HIV testing services at needle exchanges, street fairs and health clinics. I also worked at San Francisco Women Against Rape, where I advocated for rape survivors in local emergency departments and answered hotline calls late into the night. The trainings I received for these jobs were led by activists within those marginalized communities who understood and fought against bias, stigma and discrimination. Those experiences solidified my conviction that abortion access is about justice and equity, and is an essential aspect of women’s health.

During medical school at the University of Arizona, I discovered that the reason abortion services were not available to pregnant people at the University Medical Center was because a state legislator put an abortion ban into the same 1974 law that funded an expansion of the football stadium. Football was the reason patients were forced to go elsewhere for essential health care. It was also the reason I was forced to go to independent abortion clinics in Seattle and Tucson for abortion training during my fourth-year elective rotations.

I also traveled to Ecuador, where abortion is largely illegal, to participate in an elective in women’s health. I had to tell a rape survivor that I couldn’t help her with abortion care for this pregnancy—but if she wanted, she could take a rhythm method bead necklace to ensure she wouldn’t get pregnant in the future. She was raped. (In 2021, Ecuador decriminalized abortion in cases of rape. It also is allowed when a patient’s life is in danger.)

As a resident in pediatrics at a New York City hospital, I came to realize even more how systemic racism disproportionately affects children. In the Bronx, the creation of the Cross Bronx Expressway led to increased exposure to pollution, displacement of communities and degradation of neighborhoods—all interconnected and leading to increased rates of asthma and asthma-related complications. In addition to my pediatrics training, I received further abortion training. There were patients whose birth control failed them, who could not afford another child and still provide for their family, or who wanted to complete their education.

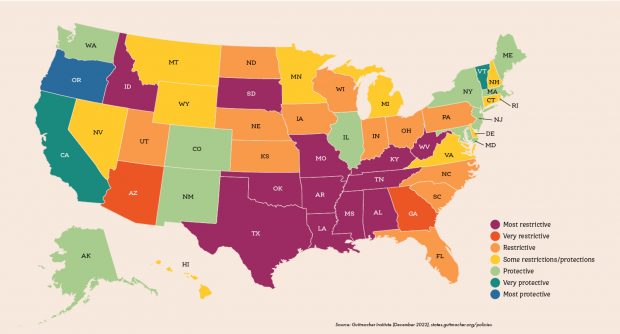

Abortion laws by state: Most Restrictive: Alabama, Arkansas, Idaho, Kentucky, Louisiana, Missouri, Mississippi, Oklahoma, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, West Virginia; Very Restrictive: Arizona, Georgia

Restrictive: Florida, Iowa, Indiana, Kansas, North Carolina, North Dakota, Nebraska, Ohio, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Utah, Wisconsin; Some restrictions/protections: Connecticut, Delaware, Hawaii, Michigan, Minnesota, Montana, New Hampshire, Nevada, Rhode Island, Virginia, Wyoming; Protective: Alaska, Colorado, Illinois, Massachusetts, Maryland, Maine, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, Washington; Very Protective: California, Vermont; Most Protective: Oregon. Source: Guttmacher Institute (December 2022), states.guttmacher.org/policies

I went on to do two fellowships in Boston, where racial disparities I saw in the city were amplified for the adolescents I cared for. There was a 14-year-old whose pregnancy was diagnosed while she was being prepped for unrelated surgery. I helped her tell her mother. She gave birth several weeks later. There was also a young woman who had obtained medication abortion pills from a family member in another country. Research shows that medication abortion pills are generally safe and do not require physician involvement. But occasionally patients require a procedure to stop dangerous vaginal bleeding, as she did. In some states, ambiguous laws make uterine evacuation illegal unless the patient’s life is “at risk”—a term that puts physicians and hospitals in the difficult position of delaying care as lawyers are consulted and committees are convened to determine whether a patient is close enough to dying to receive a procedure that physicians are trained to perform.

Later, when I moved to Atlanta as a new mother, I developed close friendships with Black moms. As my daughter became friends with their children, it hit home how hard it must be to raise a Black child in America knowing the injustices they face. I also worked at a local abortion clinic. One patient, a religious woman who worried about the stigma of abortion, drove eight hours from Ohio. Another who previously had postpartum complications cried in relief as her abortion gave her confidence she would survive to raise the children she already had.

My work as an abortion provider—especially in the South, where health disparities along racial and income lines are more pronounced—has made it clear that for people with resources, abortion is usually accessible. But for those with limited means, abortion is difficult if not impossible to access. The people I know who fight for reproductive freedom at organizations supporting women of color—groups including SisterSong and Indigenous Women Rising—say it’s clear to them that abortion restrictions and bans worsen maternal mortality and health disparities. Academic research supports that.

In the wake of the Supreme Court’s Dobbs decision overturning Roe v. Wade, those disparities have become starker.

In Arizona, where I had returned to be closer to family and work as a pediatric emergency medicine physician and abortion provider, abortion services ceased temporarily as lawyers argued for greater clarification of state laws. Abortion access in Arizona, as in other abortion-restrictive states, has been in turmoil since. Patients’ lives have been at the mercy of legislators, lawyers and judges, the majority of whom are not physicians. Some clinics in Arizona kept their doors closed due to the uncertainty of abortion legality, reopening in October when the Arizona Court of Appeals put a hold on the reinstatement of an 1864 law that criminalized abortion when Arizona was still a territory, not a state. This back and forth and lack of legal clarity has been confusing and stressful for patients, sometimes with life-threatening consequences. Pregnant patients have been affected, of course. But so have patients who need access to medications like methotrexate, which is used for the treatment of both ectopic pregnancies and autoimmune illnesses: Some have been denied potentially life-saving medication due to concern that it would be used to induce an abortion.

The turmoil has made many providers reluctant to perform abortion services out of fear of criminal penalties. The recruitment of medical students and physician trainees across the country also has been affected, with some seeking to train and practice in states where medicine is science-driven, not politically driven.

As I continue to work with and listen to people who have been advocating for decades with Black, brown and Indigenous organizations, I’ve come to realize that fighting for abortion rights is not the same as fighting for reproductive justice.

Reproductive justice is the right to have children, to not have children, and to raise the children you have in safe, sustainable communities. This means abortion access and access to clean water. This means bodily autonomy and not facing drought-induced heat strokes and natural disasters. We cannot have one without the other.

It is devastating to know that at any moment, every single day, patients in this country are being turned away from the medical care they want and need, and turned away from the futures they imagine for themselves and their families. These restrictions are impacting the way that health care providers like me approach conversations about more than abortion care. They also affect the ways we approach miscarriage management, birth control, ectopic pregnancy treatment, infertility care, cancer care and so much more due to concerns about losing one’s license, livelihood—and with potential criminal penalties in some states—even one’s freedom.

While all of the air has been knocked out of me as I raise a young girl in a state where legislators and the courts have control over our bodies, I move forward with a bit of hope, a small glimmer knowing that we—the collective we—will not stop until we build a better future for each other, that no matter who we are, where we live, who we love or how much money we make, we can live a life of dignity, respect and self-determination.

It’s around lunchtime on a weekday when two friends meet up in the Smith Campus Center’s courtyard. A dozen or more outdoor tables are buzzing with Pomona College students as they chat, eat and work under umbrellas protecting them from the high-noon sun. In the middle of the courtyard, recycled water endlessly cascades from a spout in the iconic Smith Campus Center fountain. For Anaa Jibicho ’23, the fountain is a reminder of his mission.

It’s around lunchtime on a weekday when two friends meet up in the Smith Campus Center’s courtyard. A dozen or more outdoor tables are buzzing with Pomona College students as they chat, eat and work under umbrellas protecting them from the high-noon sun. In the middle of the courtyard, recycled water endlessly cascades from a spout in the iconic Smith Campus Center fountain. For Anaa Jibicho ’23, the fountain is a reminder of his mission.

It’s midday at the Colorado Rockies’ Coors Field, still hours before first pitch. A couple of groundskeepers are busy mowing the grass with practiced precision, and another is spraying the infield dirt with a fine mist before the evening’s game.

It’s midday at the Colorado Rockies’ Coors Field, still hours before first pitch. A couple of groundskeepers are busy mowing the grass with practiced precision, and another is spraying the infield dirt with a fine mist before the evening’s game.

Alvarado’s girlhood was steeped in sports. “My parents didn’t embrace conventional thinking, particularly for Hispanic families, to let this girl be out there playing baseball with the boys, getting dirty, getting punched,” says Alvarado, born Linda Martinez. Her father was a catcher in summer baseball leagues, so she played catcher like him. “He would let me go clean the plate between innings—which is still the only plate I know how to clean,” she says with characteristic wit.

Alvarado’s girlhood was steeped in sports. “My parents didn’t embrace conventional thinking, particularly for Hispanic families, to let this girl be out there playing baseball with the boys, getting dirty, getting punched,” says Alvarado, born Linda Martinez. Her father was a catcher in summer baseball leagues, so she played catcher like him. “He would let me go clean the plate between innings—which is still the only plate I know how to clean,” she says with characteristic wit.

Lyven’s teammates wore yellow and blue ribbons to show their support, and later helped her organize a fundraiser for the Ukraine Global Crisis Relief Fund. By selling cupcakes, flowers and Ukrainian candies, Lyven raised about $1,600.

Lyven’s teammates wore yellow and blue ribbons to show their support, and later helped her organize a fundraiser for the Ukraine Global Crisis Relief Fund. By selling cupcakes, flowers and Ukrainian candies, Lyven raised about $1,600.

Before the pandemic, online broadcasts of Sagehen Athletics were a straightforward stream of the game. Now broadcasts might include multiple camera angles, instant replays, graphic overlays and play-by-play commentary.

Before the pandemic, online broadcasts of Sagehen Athletics were a straightforward stream of the game. Now broadcasts might include multiple camera angles, instant replays, graphic overlays and play-by-play commentary.

Lin’s novel had humble beginnings; it started as homework. His work was a submission for a creative writing workshop with Lethem, the much-celebrated novelist and Pomona College’s Roy Edward Disney ’51 Professor of Creative Writing and Professor of English.

Lin’s novel had humble beginnings; it started as homework. His work was a submission for a creative writing workshop with Lethem, the much-celebrated novelist and Pomona College’s Roy Edward Disney ’51 Professor of Creative Writing and Professor of English.

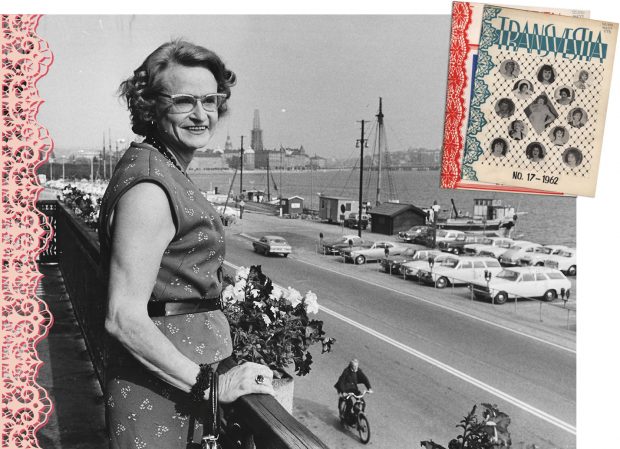

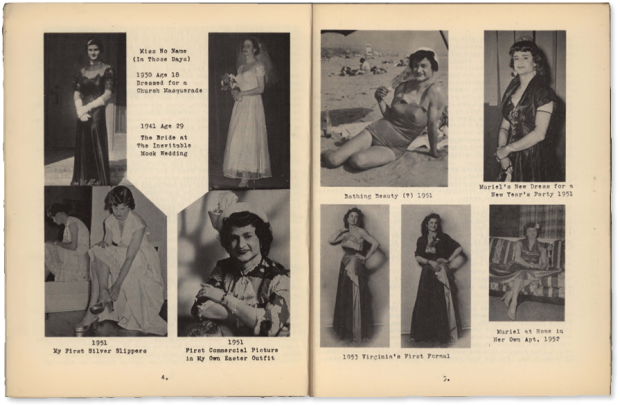

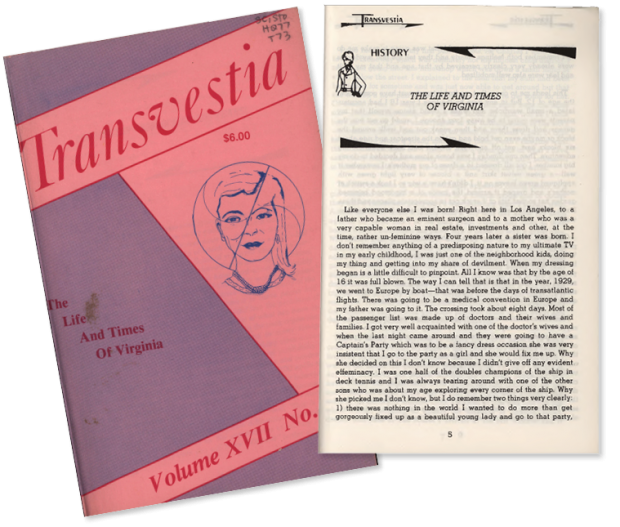

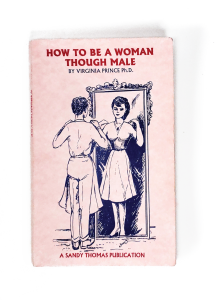

By the 1960s, Prince herself began living full-time as a woman, as she would continue to do until her death in 2009. She published a series of books, first The Transvestite and His Wife (1967) and then How To Be a Woman Though Male (1971), which doubled down on her opposition to gender-affirmation surgery. After Transvestia found some stability, Prince began bundling a selection of news about cross-dressing and gender identity in what she called her TV Clipsheet.

By the 1960s, Prince herself began living full-time as a woman, as she would continue to do until her death in 2009. She published a series of books, first The Transvestite and His Wife (1967) and then How To Be a Woman Though Male (1971), which doubled down on her opposition to gender-affirmation surgery. After Transvestia found some stability, Prince began bundling a selection of news about cross-dressing and gender identity in what she called her TV Clipsheet.