1954—2022

Emeritus Professor of Theatre Jim Taylor, who taught at Pomona for three decades before his retirement in July, passed away from complications of cancer on November 10, 2022. He was 68.

Emeritus Professor of Theatre Jim Taylor, who taught at Pomona for three decades before his retirement in July, passed away from complications of cancer on November 10, 2022. He was 68.

As a specialist in stage and lighting design, Taylor not only trained students in those arts but also designed the College’s departmental theatre productions. In recent years, he found great satisfaction in developing and teaching a course titled Theatre in an Age of Climate Change that introduced elementary concepts and principles of both climate change and theatre. He also was involved in Climate Change Theatre Action, an international series of readings and performances of short climate change plays, hosting events on the Pomona campus that sought to inspire climate action through artistic expression.

Together with Isabelle Rogers ’20, Taylor worked to write a play, This Is a River, set in Malaysian Borneo, where deforestation, palm oil plantations and dam construction have affected Indigenous people living along the Baram River. In 2020, Theatre Without Borders and the Pomona College Department of Theatre presented an online reading of the in-progress work that featured Southeast Asian actors living in Los Angeles, Chicago, London, Singapore, Malaysia and Australia.

“Jim was an extremely kind professor and advisor, and supported me at every point,” Rogers says. “His work went far beyond lighting and set design, and I was most inspired by how he encouraged students to incorporate challenging messages, like the intersection between environmental issues and gender, into our theatrical work. I appreciated how he always pushed himself out of his comfort zone to work on new projects. It was such a pleasure to collaborate with him on This Is a River, which was in many ways a passion project from his personal experience on the EnviroLab Asia trip and his knowledge about the urgency of environmental activism. I’m committed to continuing his legacy with future work and collaboration with Indigenous Kayan groups on the play.”

Taylor also had expertise in South African theatre and theatre in the Philippines, where he was a Fulbright lecturer in 1997-98.

Before arriving at Pomona in 1991, Taylor was a professor at Grinnell College, Drake University and the University of Arkansas Little Rock. He earned an MFA in theatre design and technology from Southern Methodist University in 1979 after graduating from Colorado College in 1976.

At Pomona, students who had the opportunity to study with Taylor valued his skillful teaching, his vast knowledge and his close attention to craft, but the word they most frequently used to describe him was “kind.”

In nominations for the Wig Award for excellence in teaching, students described Taylor as someone who saw “the light of each student and invite[d] them to the community with his kind heart,” and referred to him as the “kindest, most passionate, very talented, and brilliant professor.” One student noted that he was a source of comfort during the pandemic, teaching his classes with “a calm, gentle kindness that is so appreciated, especially when the world is so hard.” Students said they felt genuinely cared for by a professor noteworthy for his flexibility, compassionate listening and concern for their well-being as much as for their learning.

In addition to his contributions to dozens of campus productions—most recently as set designer for last April’s Scissoring in Pomona’s Allen Theatre—Taylor frequently worked in lighting design for Pasadena’s A Noise Within theatre and at various other venues and festivals over the years.

In describing the value of theatre to students, he said, “Studying theatre is a powerful synthesis of specialized knowledge and broader knowledge, which is important. You become proficient in expression in the short term, and prepared for learning and practice in the art for a lifetime.”

Born James Patrick Brennan Taylor in Denver in 1954, Taylor spent most of his childhood in Wichita, Kansas. He discovered his love for theatre and his talent for the backstage elements of the craft while at Colorado College.

Taylor is survived by his first wife, Mary (Twedt) Cantrell and their daughter Brennan Straka, whose family includes son-in-law Andrew, step-grandson Glen and grandson Malcolm. He is also survived by former wife Rosalie “Sallie” Canda Taylor and her daughter, Francesca “Cesca” Canda.

He previously was an associate vice president for academic planning and budgeting at UCLA, where he worked to increase transparency in allocation decisions for the $10 billion annual operating budget and developed a multi-year budget approach to strengthen the university’s finances for the future. Before joining UCLA in 2016, Roth served in a series of key leadership roles over 15 years at the New York Public Library, directing finance and strategic planning for the 92-location system, largest in the U.S. He earned a bachelor’s degree from the University of Massachusetts Amherst and an MBA from Rutgers Graduate School of Management.

He previously was an associate vice president for academic planning and budgeting at UCLA, where he worked to increase transparency in allocation decisions for the $10 billion annual operating budget and developed a multi-year budget approach to strengthen the university’s finances for the future. Before joining UCLA in 2016, Roth served in a series of key leadership roles over 15 years at the New York Public Library, directing finance and strategic planning for the 92-location system, largest in the U.S. He earned a bachelor’s degree from the University of Massachusetts Amherst and an MBA from Rutgers Graduate School of Management.

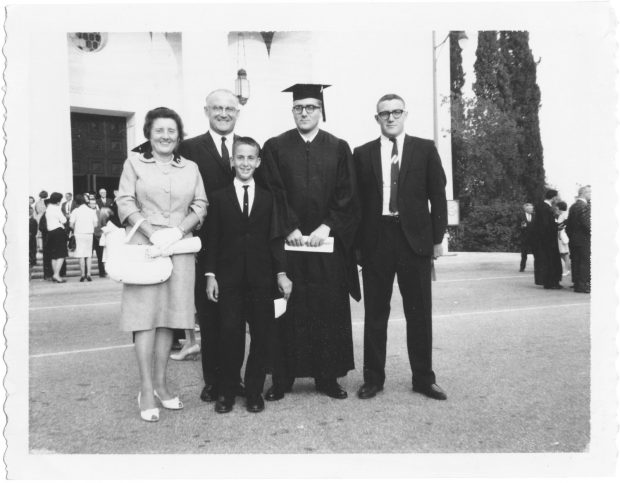

Julian Nava ’51, a professor and trailblazing advocate for public education who later became the first Mexican American to serve as U.S. ambassador to Mexico, died July 29, 2022. He was 95.

Julian Nava ’51, a professor and trailblazing advocate for public education who later became the first Mexican American to serve as U.S. ambassador to Mexico, died July 29, 2022. He was 95. Message from Alumni Board President

Message from Alumni Board President