This spring, Garrett Hongo ’73 received the 2022 Aiken Taylor Award for Modern American Poetry, an annual prize presented to a writer who has had a substantial and distinguished career. Past winners of the award, presented by the Sewanee Review each year since 1987, include Howard Nemerov, Gwendolyn Brooks, Wendell Berry, Louise Glück and Billy Collins.

This spring, Garrett Hongo ’73 received the 2022 Aiken Taylor Award for Modern American Poetry, an annual prize presented to a writer who has had a substantial and distinguished career. Past winners of the award, presented by the Sewanee Review each year since 1987, include Howard Nemerov, Gwendolyn Brooks, Wendell Berry, Louise Glück and Billy Collins.

Both a poet and a memoirist, Hongo draws heavily upon his memories of growing up on the North Shore of O‘ahu and in Los Angeles. His time at Pomona also figures prominently in his recollections, and his poem “Under the Oaks at Holmes Hall, Overtaken by Rain”  is inscribed on a plaque in the Smith Campus Center. Now a Distinguished Professor in the College of Arts and Sciences at the University of Oregon, Hongo’s collections of poetry include The River of Heaven, which was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize for poetry in 1989.

is inscribed on a plaque in the Smith Campus Center. Now a Distinguished Professor in the College of Arts and Sciences at the University of Oregon, Hongo’s collections of poetry include The River of Heaven, which was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize for poetry in 1989.

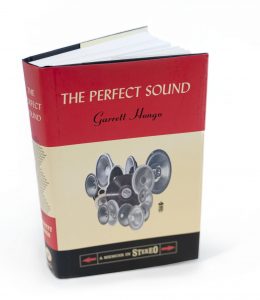

Shortly after Hongo visited campus for a reading this spring, PCM’s Lorraine Wu Harry ’97 talked with him about his recently published book, The Perfect Sound: A Memoir in Stereo, in which he delivers a personal memoir of his life as a poet vis-à-vis his decade-long quest for the ideal stereo setup. The interview has been edited and condensed for length and clarity.

PCM: You have such a strong memory for things that happened even long ago.

Garrett Hongo: People have told me that. Things are very vivid in my mind. I remember easily, as it were. The phrase from William Wordsworth that poetry is “emotion recollected in tranquility”—I need to do it or else I’m unhappy. It’s how I create who I am, in a way. It’s not just to write but to be. I live in remembrance, and it’s something I need to do.

Garrett Hongo: People have told me that. Things are very vivid in my mind. I remember easily, as it were. The phrase from William Wordsworth that poetry is “emotion recollected in tranquility”—I need to do it or else I’m unhappy. It’s how I create who I am, in a way. It’s not just to write but to be. I live in remembrance, and it’s something I need to do.

PCM: It seems like nostalgia also plays a strong role in your writing.

Hongo: I think it’s often characterized as nostalgia, but it’s a little different than that for me. Having been uprooted and moved to South Central L.A., it was something about living in a feeling that was no longer present in my life in L.A. that I had as a child in Hawai‘i. The German philosopher Friedrich Schiller talks about naive and sentimental poetry. The naive poet would be the poet who lives in emotions, and the sentimental poet is a poet who longs for the emotion previously lived. In that characterization, I would be a sentimental poet. However, I’m a sentimental poet in the sense that the emotion was not fully lived. It takes the activity of the recollection and that instigation of longing in order to complete the mental experience.

PCM: You talk about writing being for yourself. Do you did you find that this book met that need?

Hongo: People always question my obsession with hi-fi. They thought it was insanity. I didn’t even know it myself, but it was a way for me to meditate.

I really loved writing the book. I loved learning how to write the book because I didn’t know how to do it. I had all this conflict of memoir and I want to know about audio. How do you make it all work together? It was only after almost 10 years of not knowing what the hell I was doing, all of a sudden, I figured it out, and then the book came like that—boom. I’d written pieces of it. I basically wrote the whole book in a couple years, but it took eight years of not figuring it out. That seems to be my pattern for every book I write. What the hell am I doing? What is all this? I’m so awful. And I go through a lot of self-hate and castigation, and all of a sudden it breaks through.

PCM: Did you have experiences of remembering things you had forgotten?

Hongo: That’s what the book is. It’s about revelation and realization. As they say in self-help, it’s self-actualization in writing. My adoration of vacuum tubes is the same. I didn’t understand why I was so attracted to them. When I saw an amp online, I thought, “I gotta have a vacuum tube amp.” I said, “Well, I suppose that will reproduce the human voice better than transistor amps.” But what I was really doing was remembering my father. And I didn’t really realize that until I started fooling around with tube amps myself, and I remembered all those evenings with him, when he would solder together these kits and his vacuum tube amplifiers. It was also a kind of fulfillment because I would hear all the music that he could not in his losing his hearing.

As a poet, you feel confirmed in these kinds of emotions. You seek confirmation, blessing as it were, in the memories, and their pursuit gives you that. This is the way you build, as they say in psychology, personality. This is how you create subjectivity. But this is also the way ultimately you create lineage, ancestry and continuity of goodwill.

Like I say in the end of the book, my friend, Mahealani Pai, who I spent a couple of days with on the Big Island at Kaloko-Honokahau, I asked him why he was chanting or what he was chanting. He said he was chanting the names of his ancestors. I said, “Why you do that?” And he said, “So I will know them and they will know me.” And I said, “Oh, for what?” And he said, “So that when I make a decision and I chant, I will make a decision or choice in harmony with their spirits.”

It stayed in my mind. And it made sense for myself in terms of writing this book when I realized that I’m fulfilling something for my father in my own quest, and it was also a quest to become his heir, his scion, his descendant in this life, to be truly a son. So the book is a kind of Telemacheia in that sense.

PCM: What feedback have you gotten from readers? You write very much about your own experience as a Japanese American, but so many people feel a resonance with your stories.

Hongo: I think people come through the different layers of hegemonic discourse and then they respond to the work because it allows them to come through those layers. Because what they are told about identity, ethnicity, even common humanity obstructs what they feel because it puts them in positions that in fact blind and silence them to their own emotional resonances with their own lives. Poetry, not just mine, but a lot of poetry gives them the opportunity to break through those things in a way that refreshes their own affections or what has been silenced in their own histories or microhistories. I think there is a kind of intuitive connection that they feel that emerges, and I’m grateful for that.

PCM: How do you feel your time at Pomona shaped your writing and who you are now?

Hongo: I write with fondness of my time at Pomona in several episodes of my book. The liberal arts education itself afforded me a different kind of consciousness with which to engage the world. A liberal arts education gives you more freedom, allows you to be more free, allows you to be more self-creative. We’re not looking to fit. We’re looking to create.