A wildfire burns along a ridge line above a Santa Rosa vineyard a few days after the fire that devastated Ancient Oak Cellars. —Photo by Paul Kuroda

The night of Oct. 8, 2017, was unusually warm, so Ken and Melissa Moholt-Siebert left the windows of their home near Santa Rosa, California, open to the breeze much later than they usually would have. Their farmhouse was perched on 31 acres, including pasture for their modest sheep flock and 15 acres of vineyards for their winery, Ancient Oak Cellars. Its redwood beam ceilings and a stonework fireplace hand-laid by Ken’s grandfather made it perfect for cozy late-night movie sessions. Tonight the air was much warmer than the usual cool evenings typical in Sonoma; before bed, they watched a documentary about Leonard Nimoy and enjoyed the breeze.

Around 10:15, the scent of wood smoke started to drift in through the windows, but Ken and Melissa didn’t worry, imagining it could have been from some distant neighbor’s barbecue. But when the smell didn’t go away, Melissa called the police nonemergency number to ask if she should be thinking about evacuating, but the police could offer no definite advice.

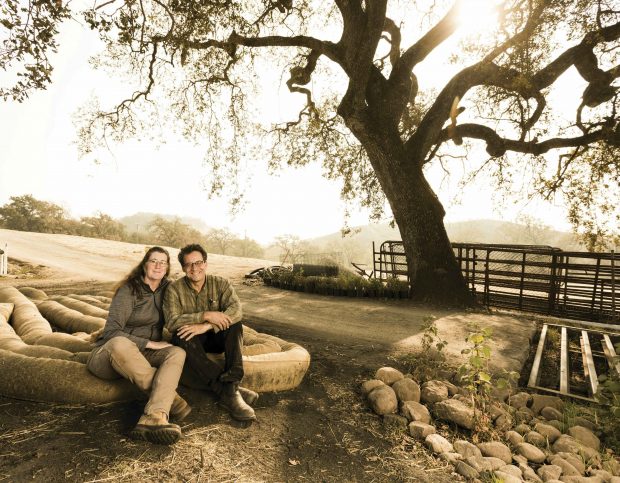

Ken and Melissa Moholt-Siebert with the new barn they’re building to replace the one that burned. —Photo by Brian Smale

Melissa fell asleep before the movie ended, but Ken stayed up thinking about the Hanley fire, which had rampaged through the area half a century before but missed the property. The wind was starting to kick up in strange, fitful gusts, flinging pine needles against the roof. Ken turned on his computer and, as was sometimes his habit, composed a poem—this one about “vanguards of embers and palls of smoke” and his grandfather wetting down the grass around the house, just in case. “Outside the sheep/Are dead silent—not a clank of the bell—but/The crickets strum and I mark the sound of sirens,” he wrote.

Just after midnight as he was finishing his poem, Ken heard a knock on the door. It was a neighbor, there to tell him and there was a fire in Fountaingrove, about three-quarters of a mile away. That was when Ken woke Melissa up. “You need to grab some stuff,” he told her. “We might have to run.”

Ken set about doing everything he could think of that might save the property if the worst were to happen. He drove to the other side of the property to turn on his agriculture pump. He grabbed a broom and got on the roof to brush the needles off. He cleaned out the gutters and tried to cut down a limb from a nearby tree that was leaning toward the house.

Meanwhile, Melissa was racing around the house gathering up what few valuables she could and packing the car. She knew, though, that there were some things she couldn’t bring even if she wanted to: not the sheep, scattered in the pasture, or the piano. And not the ancient oak down the hill in front of the house—the one she and Ken couldn’t fit their arms around, the one that was said to have predated Spanish settlement, the one that was the namesake for their winery.

There was no moon. At first, as he worked, Ken eyed the dark red glow beyond the hills to the east. By the time he was done, fire had circled around to the north and towered above the hillside in between; a sudden gust brought embers racing toward the house. One of them landed in the pasture up the hill, and before Ken could quench it, a backdraft from the south blew the flame into a wall of fire. Debris was falling all around; the drip lines in the vineyard had started to burn. Flames had begun to lick the side of the barn by the time Ken and Melissa drove away. The sound of the smoke detector inside their house followed them down the road.

Miles of rolled wire, salvaged from the ruined vineyard and awaiting reuse. —Photo by Brian Smale

Some 15 months later, on a December afternoon that’s blustery and dotted with clouds, Ken and Melissa show me around what’s left of their home. A visitor who doesn’t look too closely might never guess that a fire happened here. The hills, just greening up with winter rains, are speckled with straw that looks charmingly pastoral; a creek runs cheerfully through a little dell above the road. But the stumps of burnt trees and the blackened street sign at the front of the property tell a different story. The straw is there to prevent erosion in the newly tilled soil where the vineyard used to be. What looks like a gravel driveway branching off the little road through the center of the property is actually the spot where the farmhouse once stood.

Ken tells me about his earliest memories visiting his grandfather, back when the vineyard was only a sheep ranch and he’d come up during vacations to help his grandfather run it. “I always looked forward to coming up to the farm,” he says. “I enjoyed the physicality of it.” After the wool was collected in burlap sacks, it was his job to jump up and down on the fleeces to compact them. He would end the day sweaty and covered in lanolin, ready to hop into the back of his grandfather’s truck for a ride to the nearby lake.

Ken and Melissa met not long after those days, at Pomona in 1985 in a Human Sexuality class. People always get a kick out of that, he says wryly. She liked that he was something of a Renaissance man who studied classics, wrote poetry and attended feminist lectures. He admired her intelligence, tenacity and considerate nature. After graduation, they moved to Portland, Oregon, where he became an architect and she worked in a research lab. They had two kids, Austin and Lucy, who grew up tromping through the creek and running in the vineyard; by then the property had been planted with 10,000 grapevines.

When Ken’s grandparents died and the funding for Melissa’s lab began to ebb, they decided to take ownership of the farm, keeping the grapevines and opening Ancient Oak Cellars as a companion business. With help from farmhand Arnulfo Becerra, who had been working alongside Ken’s grandfather for decades, they learned to coax award-winning wines from the land. They continued steadily gaining experience and momentum until the night of the fire, when the flames destroyed the vineyard and everything around it entirely.

After the fire, Ken was the first to return to the property. Melissa was away on a wine sales trip that was now more critical than ever. Ken found every structure reduced to a thick layer of ash, occasionally interrupted by liquefied evidence of the recent inferno. The cast iron in the piano had split in half, and its glazing had poured out through the bottom. A pallet of wine that was set out for labeling had melted, the bottles transformed into glassy puddles only a few inches high. The steel barn roof had heated red hot and flopped over. Aluminum from Ken’s truck had pooled downhill from its charred hull.

Some of the winery’s 3,000-odd reclaimed stakes in front of vines on a neighboring vineyard. —Photo by Brian Smale

Today, Ken points out where the barn used to be—here was where the aluminum pooled, here was where the two domesticated geese and the mean rooster lived—and tells me there was little time for grief or anger in the face of such overwhelming destruction. Instead, the natural pragmatism he shares with Melissa helped them get through the first difficult months. They became “professional refugees,” as she puts it, dividing up the enormous labor necessary for rebuilding. “My new full-time job is insurance paperwork; Ken’s is being a contractor,” she says. “Maybe it’s fortunate that that’s the kind of people we are, the kind that just tackle the next project.”

The grieving process has thus been slow, with sorrow arriving in spurts. The first step for Melissa was seeing and accepting the reality of the burnt property; that really hurt. When FEMA and the Army Corps of Engineers came to help with cleanup, removing some 130 truckfuls of debris, that hurt, too. And when it became clear that the vines weren’t going to recover, that was a new, entirely different kind of pain.

Now, she says, the gentle rise of the naked, grassy hills is almost beautiful. That, in a way, feels less difficult than before. “But then,” she says, gesturing at the empty fields, “you start thinking about what isn’t here.”

After our tour, Ken and Melissa sit at a little table set up by the creek, under a canopy of oaks that has recovered heroically. “The native trees did OK,” Ken notes; that includes the ancient oak, which continues its reign over the vineyard as the land struggles to recover. Finding out the oak had survived was a bright spot in all that destruction. Maybe it meant they could, too.

Ken points out an old redwood grape stake that appears to grow out of the base of one of the oaks—the result, his grandfather always told him, of a crow alighting on the stake and dropping an acorn on the ground. The sounds of the countryside underpin our conversation: the chirp of birds and frogs; the soft baaing from the herd of sheep, diminished after the fire but still here. Nearby, some of the 3,000 modern metal grape stakes and 121 miles of wire Ken, Melissa and Arnulfo removed by hand in the last year sit in piles near a half-constructed building that will one day be a new barn.

Ken is building that barn, although he occasionally hires help; aside from the Corps of Engineers, he’s had to do most of the recovery work himself. The permitting process has been especially difficult. Few vineyards were affected the way theirs was, so no methods of streamlining have been put in place, as they often are in areas of acute destruction. In fact, in the case of most Santa Rosa vineyards, the rows of vines acted as firebreaks, mitigating damage. But the speed and ferocity of the fire, the distance of the vines away from the neighboring houses and the topography combined to make the Ancient Oak vineyard a terrible exception.

A bottle of 2016 Ancient Oak pinot noir, posed in a burnt tree stump. —Photo by Brian Smale

Even so, Ken and Melissa’s insurance, although extensive, did not cover the vineyards. Instead, Ken stretches the assistance he’s received from disaster recovery funds and farm assistance programs as far as he can by doing much of the initial construction work himself and hiring crews directly to help with more-industrial tasks. Along with wine they had stored off-site and some Ancient Oak vintages made with grapes from other vineyards, that strategy has helped Ken and Melissa limp along financially as they reconstruct their lives.

The first step after the last destroyed vine and blackened stake had been removed was to use an enormous tractor with 5-foot claws to tear through the ground of the vineyard and to add nutrients to improve soil fertility—including, Ken notes wryly, wood ash. After that, Ken and Melissa ordered 15,000 new vines, which will arrive next spring; they are taking advantage of a bad situation to increase their crop, using some extra space where the old barn used to be.

“One thing I think is hard to understand is just how long the recovery period is,” Melissa says, looking around the property and counting. Out of some 13 neighbors whose homes were damaged or destroyed, there are only a few houses under construction more than a year later. In 2019, their new vines will be planted and grow waist high; the next year those vines will need trellises. Finally, in 2021, Ken and Melissa will harvest their first small postfire crop.

But the new harvest is part of a silver lining they both recognize here: the chance to remake the farm on their own terms. Ken’s grandfather knew and loved the land, but he wasn’t a grape grower by trade. And the farmhouse was certainly cozy, but it’s not the house they would have designed for themselves. Now they will be able to update the vineyard, bringing to bear all the wine expertise 2019 has to offer. And they’ll be able to design a house for themselves. Melissa fantasizes about French doors leading out onto a patio with expansive views.

At a recent wine club dinner in Ohio, someone asked her if she had thought about cashing out: deciding not to replant or rebuild and selling instead. She shakes her head, gesturing to the creek, the oaks, the hills. Yes, the first year back has been emotionally and physically challenging, she says. For a while, they stayed in a friend’s house in town. Then another friend loaned them a pop-up camper, allowing them to camp out on their own property, showering in the open. This winter, they’re still camping, in a slightly improved structure, showering at the YMCA and eating at restaurants that are struggling to keep going after a catastrophic postfire tourist season. But still: “We came here, leaving perfectly respectable lives in Oregon, because this land is a piece of Ken’s heart,” she says. “And this hasn’t changed that.”

In some ways, Ken admits, he has enjoyed this time—even having to sleep exposed to the elements. He’s come to love the proximity to nature, the frogs, the owls, the night sounds. “Melissa and I were talking recently, and I said, ‘Maybe we just don’t build a house,’” he says. He imagines more nights under the Sonoma moon or, in case of rain, in the barn.

Melissa looks at her husband across the table and raises her eyebrows, taking in the half-finished structure. “Maybe this could be our summer house,” she replies.

Melissa and Ken Moholt-Siebert, owners of Ancient Oak Cellars, sit on bundles of straw beneath the eponymous ancient oak tree, which survived the 2017 fire that destroyed their home, vineyard and tasting room. —Photo by Brian Smale