Photos by K.C. Alfred

Osman Kibar ’92 has grown accustomed to skeptics. They don’t seem to bother him.

Kibar is the founder and CEO of Samumed, a small San Diego biotech company with new drugs in clinical trials seeking to cure arthritic knees, hair loss, scarring of the lungs, degenerative disc disease and four types of gastrointestinal cancers. Even Alzheimer’s is on the longer-term list of about a dozen targeted diseases.

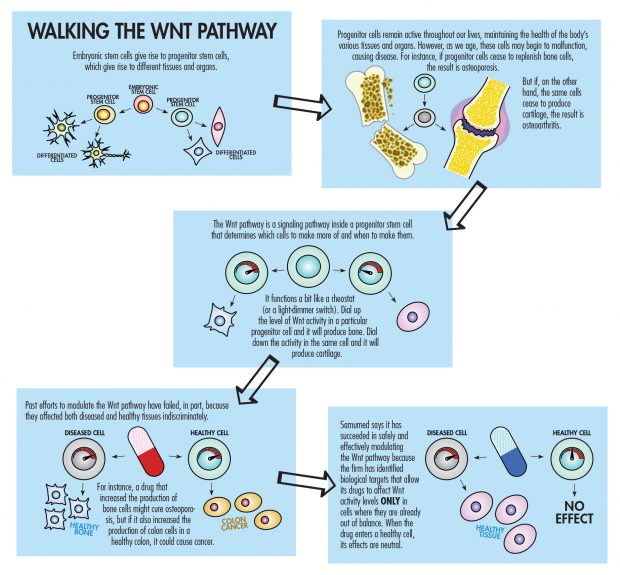

Samumed’s goals are stunningly ambitious: What Kibar and his team are trying to do is repair or regenerate human tissues through drugs that target the complex system known as the Wnt pathway, which is a key process in regulating cell development, cell proliferation and tissue regeneration.

The potential is so mind-boggling that despite being at least two years from an all-important Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval of the first of many drugs in its pipeline, Samumed already has raised $220 million in funding and is completing another round of $100 million that values the company at an astonishing $12 billion, making it the most valuable biotech startup in the world.

That eye-popping valuation and the boldness of Samumed’s venture landed Kibar, 45, on the cover of Forbes magazine in May, the featured figure on a list of 30 Global Game Changers that included Jeff Bezos, Elon Musk and Mark Zuckerberg.

Though Samumed—named for the Zen term “samu,” for meditation at work or in action—doesn’t have a product to sell yet, the confidence of Kibar, his team and key investors has soared on the early results in human trials of the hair loss and osteoarthritis drugs, which appear to show Samumed’s drugs may safely regrow hair and even cartilage.

The potential of the osteoarthritis drug alone is tantalizing to Finian Tan, chairman of Vickers Venture Partners, an international venture capital company that owns about 3.5% of Samumed and is bullish enough to be seeking to take 30% of the current round of funding.

“It doesn’t matter who cures osteoarthritis. Whoever cures it has the potential to be the largest company in the world,” says Tan, basing his calculations in part on the fact that there are some 27 million osteoarthritis sufferers in the U.S alone.

And Samumed is going after far more than fixing worn-out knees with injections instead of surgery. The firm is developing drugs that target a wide swath of diseases, many of them related to aging.

“After all is said and done, if we have just one approval, then we have failed miserably,” Kibar says. “We call our platform a fountain of youth, but piece by piece.”

“After all is said and done, if we have just one approval, then we have failed miserably,” Kibar says. “We call our platform a fountain of youth, but piece by piece.”

Born in Turkey, Kibar came to the U.S. in 1988 after graduating from Istanbul’s elite Robert College high school, which selects only those who score in the top 0.01% of Turkish students on a national standardized test. With a perfect 800 on the math section of the SAT and a 1987 European math championship in his pocket, Kibar had options when it came to college. But he bypassed more internationally famous East Coast schools for Pomona College in part for a climate more similar to that of his hometown of Izmir on the Aegean coast, and in part for the opportunity to attend Pomona on a 3-2 program that allowed him to earn a B.A. in mathematical economics at Pomona in three years, winning the Lorne D. Cook Memorial Award in economics his final year, and a B.S. in electrical engineering from Caltech two years later.

Kibar went on to earn a Ph.D. in engineering at UC San Diego and worked with his graduate school advisor, Sadik C. Esener, to found Genoptix, an oncology diagnostics firm that went public in 2007 and was acquired by Novartis for $470 million in 2011. Kibar also was a cofounder of e-tenna, a wireless antenna company whose assets were acquired by Titan and Intel. In addition, he had a stint in New York as a vice president on Pequot Capital’s venture capital and private equity team.

Samumed, founded in 2008, grew out of a company named Wintherix after legal disputes with Pfizer. It was built initially on the research of a small group of scientists including John Hood, one of Samumed’s scientific cofounders, who recently left to start a company of his own called Impact Biosciences. Hood’s track record is impressive: He created a cancer drug that led to his former company TargeGen being sold for over half a billion dollars.

Kibar’s intellect and energy are unquestioned. Consider that on the side, he is working through the course outline he found online for a Ph.D. in mathematics at Princeton, just for enjoyment. And once, on a lark, he entered an event on the World Series of Poker circuit and won. Betting against him, it would seem, is at your peril. But with goals so lofty, he does have his doubters.

The Forbes magazine cover led to an interview on CNBC that can best be described as skeptical, tossing around words like “too many red flags” and a comparison to Theranos, the medical diagnostic testing startup that went from a $9 billion valuation to being targeted by federal investigators and losing its partnership deal with Walgreens.

It’s a cautionary tale, but Kibar and industry experts say Samumed is no Theranos. As Kibar says with his typical disarming laugh, “First of all, you know the Taylor Swift song, ‘Haters Gonna Hate’?”

“Every big pharma, every small biotech, every academic center—they have been working on the Wnt pathway, trying to come up with a drug that can modulate the pathway in a safe manner,” Kibar says. “It’s been more than 30 years, and every single one has failed so far. So when we come out and say we did it, there is natural skepticism. Without seeing the data, the so-called experts’ reaction in a fair manner is, ‘Yeah, yeah, everybody has tried it. What makes these guys so special that they will have cracked the code?’ So our response to that is: Just look at the data.”

For starters, the company already has been issued dozens of patents by the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office, has five programs in clinical trials and has begun sharing data with the medical community that shows the hair loss and osteoarthritis drugs appear to be safe and effective in small human trials.

“I don’t think Theranos is a very good analogy for this company,” says Derek Lowe, who holds a Ph.D. in organic chemistry and works in the pharmaceutical industry while writing the widely read drug discovery blog In the Pipeline, which appears on a site maintained by the journal Science. “You can look at the patents and see the types of molecules [Samumed is] working with,” Lowe says. “This is not one of those where ‘we’re going to change the world but you can’t see anything’ companies like Theranos.”

Kibar shrugs off any comparisons to Theranos and its headline-grabbing fall from grace.

“They’re in diagnostics and they never shared their data, so their whole approach was: ‘Trust us, we got this,’” he says. “Being in the therapeutic field, we’re coming up with drugs; we don’t have that luxury. We cannot say, ‘Trust us, we got it.’ First and foremost, we have the FDA. The FDA is not going to take our word for it.”

The FDA is the gatekeeper, and though less than 10% of proposed new drugs ultimately earn FDA approval, the likelihood increases with each step forward in the lengthy process. The next step for Samumed’s most advanced projects, the hair loss and osteoarthritis drugs, is large Phase III studies with thousands of participants. Some 64% of drugs that begin Phase III studies are submitted for FDA approval and 90% of those are successful, according to a study cited by the independent site fdareview.org.

To begin building support in the medical community, last November at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology, Samumed presented clinical data w from its Phase I trial of 61 patients for a new drug that seeks to regrow knee cartilage to treat osteoarthritis. Animal studies already had shown that injections of Samumed’s compound caused stem cells to regenerate cartilage in rats. The Phase I study focused on demonstrating that the drug is safe in humans, but MRIs and X-rays also suggested a single dose showed what the company called “statistically significant improved joint space width” in the knees of patients who received it. A Phase II study of 445 patients is under way and expected to be complete next spring.

Samumed followed those announcements with a presentation of Phase I data from its trial to treat baldness at the World Congress for Hair Research, and in March presented data from its completed Phase II hair-growth trial to the American Academy of Dermatology. That study of 310 participants showed that hair count in a one-square-centimeter area of one group of subjects’ scalps increased by 7.7 hairs (6.9%) and by 10.1 hairs (9.6%) in another, though the largest increase was in the group that received the lower of two doses. The control group lost hair.

Tan, the venture capitalist known for making an early bet on Baidu, the Chinese answer to Google, sticks to his assertion that Samumed, if successful, could be bigger than Apple.

“I think the potential is unbelievable. With the Wnt pathway, when it eventually is totally controllable, the sky is the limit because it is involved in cell birth, cell growth and cell death,” Tan says. “The key is nobody has been able to successfully manipulate the Wnt pathway safely and effectively. Samumed appears to be doing it in human trials.”

So far, the trials are small, preliminary studies, both Samumed and industry observers note. Since the groundbreaking discovery of Wnt signaling in the early 1980s, no other attempts to modulate it have succeeded, and tinkering with a system that regulates cell development clearly involves risk. In an article titled “Can We Safely Target the Wnt Pathway?” in Nature Reviews Drug Discovery, a publication of the journal Nature, Michael Kahn, a professor of biochemistry and molecular biology at the University of Southern California’s Keck School of Medicine who holds a joint appointment in pharmacy, likened the Wnt pathway to a “sword of Damocles.” Put most simply, targeting the Wnt pathway might cure cancer, but could also cause it.

“It is a death or glory target,” says Lowe, the industry blogger.

That, of course, lends itself to discussion of the high-stakes gamble reflected in the company’s $12 billion valuation. Investors include many with close ties to Kibar, and he says remaining privately held allows Samumed to proceed without shareholder pressure for quick results and requirements for public disclosure in what is by definition a long-haul endeavor. Inter IKEA Group, the retail giant’s private venture firm, has placed the largest bet among Samumed’s mostly anonymous outside investors. The operative phrase is “caveat emptor.”

“Anybody who is investing in an early-stage biopharma company has to be ready for it not to work out, because most of these don’t,” Lowe says. “The hope is just like if you’re developing some great new app: The hope is this is going to turn out to be something big.”

It’s a boom-or-bust world. Kibar and his team know that but remain confident.

“From a technical perspective, we don’t lose any sleep anymore, because we have demonstrated safety and efficacy and disease modification in enough programs that we believe we have already validated the broader platform,” Kibar says. “In terms of funding, we’re also in a fortunate position in that we have all the money we need to bring these programs all the way to approvals. With our first approval, the company will become cash-flow positive. And we have enough cash in the bank to get us to multiple approvals, so that gives us additional diversification.”

The management team still on board after Hood’s departure is solid, united by decades-old friendship: Three of Kibar’s top executives also went to the elite Robert College high school. But he rejects any suggestion that he has simply surrounded himself with high school chums, saying instead that they have all reached such heights in their careers that the only reason a startup could have lured them is because of their confidence in him and his project.

The chief financial officer, Cevdet Samikoglu, cofounded a hedge fund, Greywolf Capital Management, after becoming a director and portfolio manager at Goldman Sachs following Harvard Business School. The chief legal officer, Arman Oruc, earned a master’s in economics from the University of Cambridge and a law degree at UC Berkeley before becoming a partner in Simpson Thacher & Bartlett, where he represented clients like MasterCard, Ericsson, LG and Novartis. And the chief medical officer, Yusuf Yazici, is an internationally known rheumatologist who has maintained his role as an assistant professor at NYU, where he is director of the Seligman Center for Advanced Therapeutics, which conducts all clinical trials in rheumatology for the NYU Hospital for Joint Diseases.

They are on a journey together along a path that still holds suspense.

“These are all long-term projects, taking a molecule from discovery to animal studies to clinical and then commercialization. You’re talking a minimum 10 years,” Kibar says. “The data—we are sharing it with the FDA, and we shared it with the doctors. Beyond that, no matter what we share, people will either not understand or not care or not believe. So those are the skeptics. And in certain programs, they may turn out to be right. We haven’t done it yet.”