eric

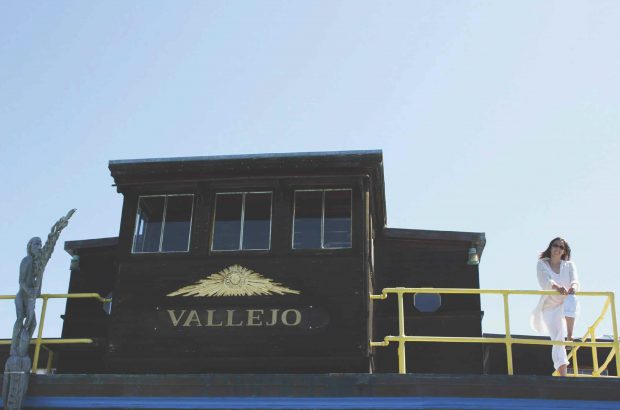

On the first morning of my writing residency, I looked out the window and was filled with dread. ‘It’s back,’ I thought. For months I’d been battling episodes of vertigo, which seemed to strike after changes in elevation. And since I’d just flown from the mountains of Colorado and landed at sea level, I was sure it was back, and just in time to thwart this dream opportunity. Fortunately, what I thought was an imbalance in my inner ear was actually the gentle swaying of the outside world. After all, I was on a boat, a houseboat in fact—the SS Vallejo—home to the newly created Varda Artist in Residence (VAR) Program.

The Vallejo had a rich history before landing in the hands of the current owners and program directors. Originally a passenger ferry in Oregon, after being decommissioned, the Vallejo was due to be sold for scrap metal. Fortunately, in the magical year of 1947, Jean Varda bought the boat and turned it into an artists’ haven in Sausalito, CA. Varda invited others, such as Alan Watts, Gary Snyder, and Allen Ginsberg to join him. Soon the boat was a flourishing artists’ community, complete with a reputation for wild parties that experimented with alternative ways of thinking. The Vallejo also became home to many of the Beat poet gatherings, as well as the conversations Alan Watt recorded that came to be known as the “Houseboat Sessions.” After Varda’s death in 1971, the boat changed hands several times. In 2015 the Vallejo officially became the home of the VAR program.

Après Le Deluge

After Rimbaud

After the idea of the deluge

ended, a little hare appeared

in the moving flowers, spoke

of rainbows lighting the spaces

of a spider’s web: the colors,

it said, can be seen only

after the years of darkness.

But the stones, the old

unbelievers, remained unmoving

in the streets, and watched

as the same stalls were erected,

the same ships were hauled to sea.

Only the children, looking out

from their big glass houses, saw

the New World like a painting,

like something from a dream.

Among the other artists with me were a rock musician from New York, a sound artist from Portland, Ore., and a visual artist from New Zealand. Not only was I the only writer, I was also the program’s first poet. Before my arrival, I’d just completed my first full-length poetry collection, My Dark Horses, and I was waiting to hear news from publishers. Given that I’d been writing about the rather heavy topic of my childhood, I felt both a sense of accomplishment and relief after finishing the book, and I was looking forward to using the residency to tackle something new. Originally I’d planned to translate the French poet Arthur Rimbaud’s Illuminations. However, only a few days into the project, and with the boat’s rich inspiration, I found myself creating a sheaf of my own new poems that built off Rimbaud’s poetry.

I was delighted by the simple yet elegant space I’d been given for my work. My room was a freshly painted white, and three of its walls had expansive views of Sausalito Bay. Blooming plants were in every corner, and the large windows allowed the fresh air and the music of the ocean and birds to enter. I faced my desk toward the long view of the water and unpacked my favorite collected poems: by Philip Larkin, Robert Frost, Sylvia Plath, and Donald Justice. I placed them next to my computer and was ready to work.

However, no progress was to be made without a strong cup of coffee. I unpacked my stovetop espresso maker and beans and figured I’d be set. After looking around the kitchen, I was surprised to find I’d be grinding my beans by hand and working up a sweat from turning the crank hundreds of times. I eventually grew accustomed to this ritual and even came to enjoy it. But as it turned out, the real coffee challenge was yet to come. One of the unique things about houseboat living is that one must climb a ladder to reach one’s room. Other than the possibility of a drunken stumble or unexpected bout of vertigo, it hadn’t occurred to me that the ladder would be an obstacle—I was forced to devise a system. First, I’d take a few sips to lower the coffee level in my mug and to give myself a small shot of caffeine, should I need to make a quick save during transport. Then, I’d hold the side of the ladder with my left hand moving the coffee up one rung at a time with my right. Meanwhile, my feet followed suit, one rung at a time, until my coffee and I were both safely delivered up the ladder to my desk and my computer.

I’m sure this looked ridiculous, particularly to the others who simply drank their coffee in the kitchen and avoided the drama altogether. But aside from enjoying my coffee in solitude, I’d developed this quirk of needing a mug of coffee beside me while I worked; thus the struggle was worth the effort.

Vagabonds

After Rimbaud

Oh, pitiful brother,

I cannot be your sister

you cannot be my brother,

since you are still a mistress

to our late mother—

Many years have passed,

and these days I wonder,

what’s become of you

and what foreign land

do you these days inhabit?

Russia, Japan, China,

in that mind of yours

you were never right.

But what if now we met?

Could I restore you

to your original state;

or would you drag me,

just as She did,

into your dark room

of old howling sorrows?

Bringing an empty coffee mug, or anything for that matter, down the ladder was much easier than taking it up. When I first arrived, I’d made a dozen or so trips up and down carrying my clothes and books in small, backpack-sized deliveries. But at one point, the rock musician suggested to me: Why not just throw your clothes down? An excellent idea I wished I’d thought of myself! This began the jettisoning of shorts, dresses, and pants to the main level of the boat in a Great Gatsby-esque moment of liberation. I’m sure, at the very least, the Beat poets would have approved.

The program allowed as much or as little contact with the outside world as we liked. Some of the artists spent their days exploring the offerings of San Francisco, while others stayed on the boat. I was of the latter, less hip group. Among other reasons for this was the chance to observe a tragic pair of resident seagulls. This couple squawked outside my room early each morning; then walked on the roof with such deliberation that I wondered if two very serious lawyers were debating above me. One day I noticed that the gulls had built their nest precariously atop one of the pier’s wooden piles. Upon some investigation, I learned that each year their nest fell terribly into the ocean—the eggs lost to the deep blue. The parents cried out in painful squawks of loss, buried their beaks dejectedly in each other’s feathers, and seemed to mope around the boat until their grief passed. And yet each spring they’d rebuild their nest in the same place, and the same disaster ensued. I wondered what kinds of bird-brained behavior my fellow artists were witnessing on the streets of San Francisco.

From time to time the Vallejo hosted its share of social gatherings. These were nothing like the famed wild parties of the Beat Generation, but rather intimate events that allowed each artist to display his or her work. On our last evening, we ate salmon from the local fishmonger, broiled with fresh cherries. We made a colorful salad, cut thick slices of bread and drank plenty of California wine. Each of us gave a short presentation describing how the boat had inspired or changed our work during our stay. Later that night, we piled into a rowboat and quietly reflected on our time spent on the Vallejo. For my part, I chose to row—pushing the old wooden oars quietly through the dark waters.

NOTE: The Vallejo’s owners have requested that we note that the boat is not open to the public.