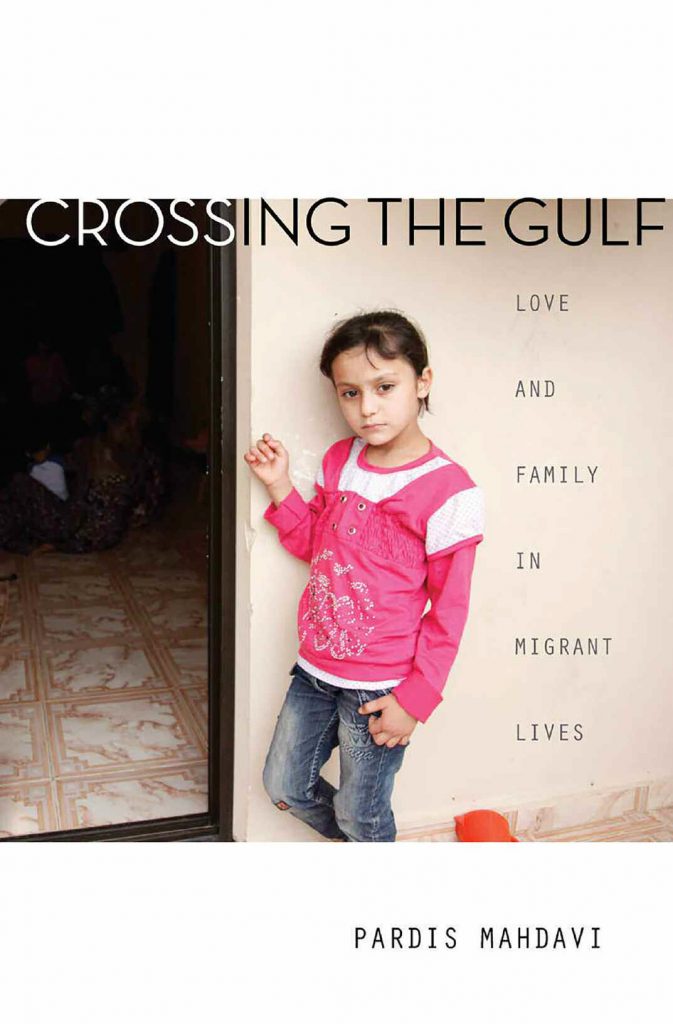

In her new book, Crossing the Gulf: Love and Family in Migrant Lives, Associate Professor of Anthropology Pardis Mahdavi tells heartbreaking stories about migrants and trafficked mothers and their children in the Persian Gulf and talks to state officials, looking at how bonds of love get entangled with the law. Mahdavi talked to PCM’s Sneha Abraham about her book and the questions it poses about migration and families. This interview has been edited and condensed.

In her new book, Crossing the Gulf: Love and Family in Migrant Lives, Associate Professor of Anthropology Pardis Mahdavi tells heartbreaking stories about migrants and trafficked mothers and their children in the Persian Gulf and talks to state officials, looking at how bonds of love get entangled with the law. Mahdavi talked to PCM’s Sneha Abraham about her book and the questions it poses about migration and families. This interview has been edited and condensed.

PCM: Talk about the relationship between family and migration.

MAHDAVI: Our concept of family has been reconceptualized and reconfigured in and through migration. People are separated from their blood-based kin; they’re forming new kinds of fictive kinship in the labor camps or abroad. Some people migrate out of a sense of familial duty, to honor their families. Sometimes they get stuck in situations which they feel they can’t get out of because of their family and familial obligations. Other people migrate to get away from their families, to get away from the watchful eyes of their families and communities. Families are not able to necessarily migrate together, and children are not able to migrate with their parents; they’re in a more tenuous relationship now than we would recognize when we look at migrants really just as laborers.

Laws complicate those relationships. Laws on migration, citizenship and human trafficking create a category of people caught in the crossfire of policies—and those people are often women and their children, and often they are trapped in situations of illegality.

PCM: Would you tease out the question of migration versus trafficking? That is something you’re exploring in your book.

MAHDAVI: I think it’s a real tension that needs to be teased out in the larger discourse. That’s the central question. What constitutes migration? What constitutes trafficking? It’s very difficult and that space is much more gray than we think. We’ve tended to assume that women in industries like the sex industry are all trafficked. We assume if there’s a woman involved, it’s the sex industry; if it’s a minor, it is trafficking; if it’s a male, if they’re in construction work, that’s migration. But that’s just not true. Trafficking really boils down to forced fraud or coercion within migration. It’s kind of a gray area, a much larger area than we think. The utility of the word “trafficking” really is questioned in the book. How useful is that word? The very definitions of migration and human trafficking are extremely politicized and depend on who you ask and when. Some people might strategically leverage the term, whereas other people strategically dodge it.

Some interpretations have positively elevated the importance of issues that migrants face; other people might say that the framework is used to demonize migrants or further restrict their movement.

PCM: What’s an example of a policy that affects these issues of migration and trafficking?

MAHDAVI: The United States Trafficking in Persons Report (TIP) is one policy, kind of a large one, to the extent that the report ranks all the countries into tiers and then makes recommendations based on their rankings. And sometimes the recommendations that the TIP report makes actually exacerbate the situation instead of making it better.

For instance, the United Arab Emirates is frequently ranked Tier 2, or Tier 2 Watchlist [countries that do not comply with minimum standards for protecting victims of trafficking but are making efforts], and the recommendation is that there should be more prosecutions and there should be more police. Now, the police in the U.A.E. are imported oftentimes, and from my interviews with migrant workers, it’s often the police who are raping sex workers and domestic workers. So you double up your cops, you double up your perpetrators of rape. So that is a policy that’s not helping anyone.

Other policies are more tethered to citizenship. They don’t have soil-based or birthright citizenship in the Gulf. Citizenship passes through the father in the U.A.E. and Kuwait. Citizenship also passes through the father in some of the sending countries, for instance, up until recently Nepal and India. So that means a domestic worker from India or Nepal, five years ago, who goes to the U.A.E., perhaps is raped by her employer or has a boyfriend and gets pregnant and has a baby, that woman is first incarcerated and then deported because as a guest worker she is contractually sterilized, and that baby is stateless because of citizenship laws that are incongruent.

There is a whole generation of people that have been born into this really problematic situation.

PCM: You write about “children of the Emir.” Who are they?

MAHDAVI: So, “children of the Emir” is kind of the colloquial nomenclature given to a lot of the stateless children. They could be children of migrant workers, children who oftentimes were born in jail; maybe they were left in the Gulf when their mothers were deported. They may have been left there intentionally. It’s not clear, but they’re stateless children who were born in the Gulf. And some of them are growing up in orphanages; others are growing up in the palaces. There was a lot of tacit knowledge about these children and rumors that the Emir or members of the royal family are raising them. But nobody could find the kids. Nobody knew where they were or if it was actually true that they were being raised in the palaces or not. That was rumor until I conducted my research and I was able to confirm that by interviewing these children. And it is true that some are raised in various palaces, given a lot of opportunities, and treated very well.

So now many of them are adults, living and working in the Gulf but still stateless. Recently there’s been a slew of articles that have indicated that some of the Gulf countries, the U.A.E. and Kuwait included, are engaging in deals with the Comoros Islands where, in exchange for money to build roads and bridges, they are getting passports from the Comoros Islands. Initially it was thought that they would just get passports to give to these stateless individuals, but the individuals had to remain in the Gulf. However, a closer look at some of the contracts indicates that some of these stateless individuals who are being given Comoros citizenship actually will have to go to the Comoros Islands, which is a very disconcerting prospect for many stateless individuals in the Gulf. And for people who are from the Comoros Islands, they are now thinking, “Oh, our citizenship is for sale,” to stateless individuals who are suddenly told that they are citizens of a country they’ve never even heard of.

PCM: You write about something you call “intimate mobility.” What is that?

MAHDAVI: Intimate mobility is kind of a trope that I’m putting forward in the book. Basically, it’s the idea that people do migrate in search of economic mobility and social mobility—which is obvious to a lot of people—but people also migrate in search of intimate mobility, or a way to mobilize their intimate selves. For example, they migrate to get away from their families in search of a way or space to explore their sexualities. Some form new intimate ties through migration. For others, their intimate subjectivities are challenged when one or more members of the family leave. My book is asking us to think about how intimacy can be both activated and challenged in migration.

PCM: What does it mean to mobilize one’s intimate self?

MAHDAVI: There was a young woman who migrated, who left India because her parents wanted her to get married in an arranged marriage. But she left because she saw herself as somebody who would not want to marry a man. She identifies as a lesbian, and so she migrated to Dubai so that she could explore that sexual side of herself. So that’s some of the intimate mobility I’m talking about.

On the flip side, I talk about intimate immobility and I talk about how people’s intimate lives, as in their intimate connections with their children back home or their partners back home, become immobilized when they are in the host country. Their intimate selves are immobilized because they can’t fully express their love for their children or for their partners. And also women who are guest workers or low-skilled workers legally cannot engage in sexual relations so they can’t as easily engage in a relationship.

Pardis Mahdavi is associate professor of anthropology, chair of the Pomona College Anthropology Department and director of the Pacific Basin Institute. Crossing the Gulf is her fourth book.