Photos by Robert Durell

COURT STREET IN MARTINEZ, California, lives up to its name. On a gray morning in December, four imposing stone courthouses in a row loom out of the cold fog, steamy glass doors accepting the occasional be-suited prosecutor or latecomer for jury duty.

Inside one of those courthouses this morning, Emi Young ’13 is waiting in a dimly lit courtroom gallery for a restitution conference to begin. Young, who works as a deputy public defender for Contra Costa County, will be representing a client who pleaded guilty to possession of a stolen vehicle. As part of the conviction process, she is participating in discussions about how much money will be awarded to the victim to help with damages—discussions that are often, but not always, straightforward, since both sides need to agree that the restitution requested is sufficiently related to the crime. (“I had a vandalism case where the city requested compensation for all of the tagging or graffiti that they thought were similar from the preceding year,” Young notes.)

The beige-carpet-on-beige-wood courtroom is crowded with cases, and the judge moves swiftly through the docket. Normally the prosecutor would have conferred with the victim’s assigned restitution specialist by now, but this time that hasn’t happened. So, a few minutes before the conference begins, Young hands him her copy of the handwritten list, which totals $126,000. Along with the value of the stolen vehicle, the victim is requesting restitution for multiple other vehicles, several marine batteries and damage to a barn door—all seemingly unrelated to the crime for which her client was convicted.

“That… is a lot of money,” the prosecutor says, running his eyes down the list. When the judge has turned her attention to the case, she agrees, noting with raised eyebrows that the request would make for an “interesting” hearing. “What do you want to do, Ms. Young?” she asks. A pause, then Young and the prosecutor agree to delay the conference, giving more time to talk to all parties and perhaps find a solution.

“It’s frustrating that he didn’t have more time to look at the request before,” Young says as she walks through the fog back to her office a few blocks from the courthouse. Under normal circumstances, these things can take as little as 20 minutes—that is, when the prosecutor is prepared and when victims limit themselves to amounts directly related to the crime and provide adequate documentation.

It’s lucky, she notes, that her office had not yet closed the case file, leaving her client without representation. Then, the court might just have sent a letter instructing him to request a hearing or agree to pay the full amount—and many of her clients are transient, with no fixed addresses and unreliable mail service.

But such frustrations are an inherent part of a job with limited time, limited funding, limited attention. “I talk about the system I work in as the ‘criminal legal system,’” she says. “The term ‘criminal justice system’ is aspirational. It’s not the reality for many people.”

AT 28, YOUNG, WHO favors bold colored scarves, long sweaters and a silver hoop in her nose, is, well, young for her profession. She was born in Omaha, Nebraska, and her parents divorced in her early childhood. Growing up with a single, Japanese mother profoundly shaped her— especially in a school district that had been created by conservative white parents who were trying to skirt anti-segregation laws. “It felt like our family was very different,” she says. “I know my mom also really struggled sometimes.”

AT 28, YOUNG, WHO favors bold colored scarves, long sweaters and a silver hoop in her nose, is, well, young for her profession. She was born in Omaha, Nebraska, and her parents divorced in her early childhood. Growing up with a single, Japanese mother profoundly shaped her— especially in a school district that had been created by conservative white parents who were trying to skirt anti-segregation laws. “It felt like our family was very different,” she says. “I know my mom also really struggled sometimes.”

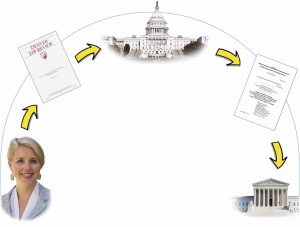

As part of continued efforts to support her family, Young’s mother went back to school to become a paralegal. She sometimes brought home articles about important Supreme Court cases and news from the legal system to share with her daughter, who at the time aspired to be a musician. It wasn’t until Young attended Pomona, graduating in 2013, that she changed her mind.

Her experience at Pomona was profoundly “consciousness raising,” she says. Conversations happening on campus helped her understand earlier experiences from her own life in a new light—her experience as a biracial person in a school district with segregationist roots, for example. And it was at Pomona that she first learned about what she calls the “disparate impacts of our legal system on certain communities.”

That nascent interest prompted Young to major in political science and philosophy; her Pomona education “helped me have a vocabulary for certain ways in which people are systemically disenfranchised,” she says. She volunteered for a semester at the Camp Afflerbaugh-Paige juvenile detention facility near campus, producing Othello with some of the students. While she was there, one of the teenaged boys disappeared for a week. When he returned, she was struck by how dramatically different he was: subdued where he had been animated, depressed where he had been bright and playful, cracking jokes.

It turned out that he had gotten in trouble and been kept in isolation for some time as a disciplinary measure. “This doesn’t seem fair or good for a person who we hope will turn out to be happy and productive,” she remembers thinking. “I feel like I can’t advocate on his behalf right now, but it’s something I’d like to be able to do someday.” In pursuit of that goal, she attended law school at Stanford and spent her first summer interning at the New York Civil Liberties Union—but was surprised to find herself unhappy with the experience, which felt too divorced from the people she hoped to help. “I realized I should be trying to come at it from a different angle,” she says.

Young is aware that public defender stereotypes paint a picture of a harried, overburdened lawyer who doesn’t fight for her clients, “interested in trying to plead you out as quickly as possible because we don’t have the time or resources to defend you adequately.” But Contra Costa’s public defenders maintain one of the highest trial rates in California, part of the reason she applied for a job here. Encouraging plea bargains “does not lend itself towards keeping the system accountable or ensuring accurate or fair results,” she says.

THE ROLE OF PUBLIC DEFENDER doesn’t come with much of a runway. Once she graduated from law school, Young clerked for several months at the Contra Costa Public Defenders Office—then began representing a full load of clients on misdemeanor charges soon after she passed the bar in January 2017. “When I got hired, I quite literally had three days’ transition to begin representing 110 clients, some of whom had trials set,” she remembers with a shudder and smile.

THE ROLE OF PUBLIC DEFENDER doesn’t come with much of a runway. Once she graduated from law school, Young clerked for several months at the Contra Costa Public Defenders Office—then began representing a full load of clients on misdemeanor charges soon after she passed the bar in January 2017. “When I got hired, I quite literally had three days’ transition to begin representing 110 clients, some of whom had trials set,” she remembers with a shudder and smile.

These days, she works instead with clients facing felony charges, which run the gamut from evading the police to gun possession to attempted murder—around 40 at a time and between 50 and 60 hours a week. It’s a more manageable load than she had in misdemeanors: the cases move slower because there’s more at stake, so there’s more time to work on them. That creates opportunities to occasionally play her violin; take a bread-making class; or go on walks with her mother (who moved to the Bay Area several years ago) and the family dog, Teeter.

Beyond the frantic pace, Young has slowly adjusted to a professional life that can demand a difficult balancing act between practicality and justice. Some clients with immigration concerns prioritize protecting that status, even beyond proving their innocence; some clients value the chance to have the proverbial “day in court” and tell a judge what happened over the safety of a plea bargain. There have been cases where she believed her clients were innocent but struggled with how to advise them, because their prior history put them at deep risk if they were to be convicted of a serious crime. And when her clients are kept in custody as they await trial, she must decide how to ask to schedule their hearings, keeping in mind that the longer she spends preparing their cases, the longer they’ll spend away from their families, friends, worlds.

“There’s an older philosophy that as attorney you’re the person who is educated and knows the law, and you should be the person responsible for making decisions about best outcomes,” she says. Instead, “our duty is to learn about and understand our client’s perspective.”

It’s also a professional life that melds stereotypical courtroom drama with the ordinary, obligatory mechanics of the justice system: jail visits, written motions, the series of hearings that precede a jury trial. The fabric of Young’s daily routine is threaded with the half-hour drives between courtrooms in various towns; the waits to get into jails; the police officers who are late to give testimony; the judges trying to sort out the daily docket. In the week that I shadowed her, she had three separate hearings delayed at the last minute. That week featured pockets of the pursuit of justice, yes—but they were glued together with pauses during which judges took bathroom breaks and bailiffs watched pet videos on the phones of district attorneys.

The stops, starts and delays can be “really frustrating,” she says, but they have had a surprising benefit: teaching her adaptability, honing her capacity to adjust and respond to new tasks at a moment’s notice. Before this work, “I was very good at planning for something, preparing a lot for something and doing it,” she says. “But the thing you learn with this job is that you can’t prepare for all the possibilities. You have to be okay with the unexpected sometimes.”

AFTER THE CANCELED RESTITUTION HEARING, Young settles in at her office to spend the rest of the day wading through the seas of mundane justice: drafting motions, reviewing new evidence, preparing for an upcoming trial. The room is small but friendly, featuring a coffee machine tucked into a corner and an assortment of button-down shirts hanging off the doorknob for clients to try on. The walls are decorated with photos of Teeter and a few pieces of art.

Beside a selection of client thank you notes hangs a Ta-Nahesi Coates quote on a note card that reads, in part: a society that “can only protect you with a club of criminal justice has failed at enforcing its good intention or has succeeded at something much darker.” It’s a reminder of the losses and disappointments: the young man who was prevented by his co-defendant from taking a probation plea deal and ended up in prison; the client whose immigration status she worked to protect during a DUI case but who ended up in ICE custody later, anyway.

Even victory, when it comes, has been bittersweet. Young remembers one client who was charged with elder abuse of his own mother. During the trial, it became clear that the mother’s mental state was deteriorating, especially as her reports of abuse were not corroborated by evidence; she died soon after the verdict. Although Young’s client was cleared of wrongdoing, she struggles to find vindication when thinking about how he must have felt—accused of a cruel and violent act, separated from a beloved parent during the last weeks of her life. “There’s nothing that the acquittal in and of itself can do to repair the damage,” she says, sighing.

A victory is “gratifying,” she adds, but “just because a case was ultimately dismissed, or was acquitted, it doesn’t mean the experience hasn’t taken a toll.” Even with positive outcomes, her clients still deal with negative impacts: the costs of bail, missed work and immigration risks.

Taking a moment to celebrate the work that’s done can be difficult when there’s always another seven things to do. Yes, today’s delayed restitution hearing was a small victory. In this case, she hadn’t been reassigned, so she was able to continue to represent her client in a quest for a fairer outcome. She’ll likely be able to renegotiate that request, saving him money and helping him start fresh.

Tomorrow will bring another hearing, another jail visit, another trial. More new clients will arrive, more new evidence will be unearthed, as the American penal organism churns on. But today, she added a little justice to that system. That has to be enough.

The 9 Pitfalls of Data Science

The 9 Pitfalls of Data Science Living the California Dream: African American Leisure Sites During the Jim Crow Era

Living the California Dream: African American Leisure Sites During the Jim Crow Era Heartthrob

Heartthrob Donuts Are Meant to be Eaten

Donuts Are Meant to be Eaten Dreaming of Arches National Park

Dreaming of Arches National Park A Knowledge Representation Practionary: Guidelines Based on Charles Sanders Peirce

A Knowledge Representation Practionary: Guidelines Based on Charles Sanders Peirce Chasing Gods

Chasing Gods US Democracy Promotion in the Arab World: Beyond Interests vs. Ideals

US Democracy Promotion in the Arab World: Beyond Interests vs. Ideals

Sometime this fall, the Pomona College Museum of Art will cease to exist, and the Benton Museum of Art at Pomona College will be born in its beautiful new quarters on the opposite corner of the intersection of College and Second. To prepare for that change, for the past few months, the museum’s associate director and registrar, Steve Comba, has been overseeing the effort to inventory, pack and safely move approximately 15,000 valuable and often fragile art objects from the museum’s old storage into the new. Already in their new home are the artifacts of the museum’s Native American collection, previously stored in the basement of Bridges Auditorium and brought out mainly for visiting schoolchildren.

Sometime this fall, the Pomona College Museum of Art will cease to exist, and the Benton Museum of Art at Pomona College will be born in its beautiful new quarters on the opposite corner of the intersection of College and Second. To prepare for that change, for the past few months, the museum’s associate director and registrar, Steve Comba, has been overseeing the effort to inventory, pack and safely move approximately 15,000 valuable and often fragile art objects from the museum’s old storage into the new. Already in their new home are the artifacts of the museum’s Native American collection, previously stored in the basement of Bridges Auditorium and brought out mainly for visiting schoolchildren.

Growing up in Alabama, the son of two history scholars, develop an abiding interest in ancient civilizations. Fall in love with things even older at age 5 when your mom brings you a fossil trilobite half a billion years old from a vacation in Utah.

Growing up in Alabama, the son of two history scholars, develop an abiding interest in ancient civilizations. Fall in love with things even older at age 5 when your mom brings you a fossil trilobite half a billion years old from a vacation in Utah. Discover in grade school that you can find fossils of sea creatures 80 million years old right behind your school. Carry that fascination with the geological record through high school to the College of William and Mary.

Discover in grade school that you can find fossils of sea creatures 80 million years old right behind your school. Carry that fascination with the geological record through high school to the College of William and Mary. In college, go on a road trip organized by a faculty mentor to the Grand Canyon and the White Mountains of California, including an unexpected detour to Utah where you encounter the source of your very first trilobite, the House Range.

In college, go on a road trip organized by a faculty mentor to the Grand Canyon and the White Mountains of California, including an unexpected detour to Utah where you encounter the source of your very first trilobite, the House Range. Go to the University of Cincinnati for your master’s in geology. Take a course with your future Ph.D. advisor, then on sabbatical from UC Riverside, and find her interest in studying ancient ecosystems through their fossils contagious.

Go to the University of Cincinnati for your master’s in geology. Take a course with your future Ph.D. advisor, then on sabbatical from UC Riverside, and find her interest in studying ancient ecosystems through their fossils contagious. Following your mentor to California for doctoral studies, take your fascination with that first trilobite full circle when you decide to focus your Ph.D. thesis on the Cambrian ecosystems recorded in Utah’s House Range.

Following your mentor to California for doctoral studies, take your fascination with that first trilobite full circle when you decide to focus your Ph.D. thesis on the Cambrian ecosystems recorded in Utah’s House Range. As a teaching assistant at UC Riverside, find that you love teaching and get your first administrative experience when you’re hired as director of a program to train new science teaching assistants.

As a teaching assistant at UC Riverside, find that you love teaching and get your first administrative experience when you’re hired as director of a program to train new science teaching assistants. Get hired for a one-year position as visiting assistant professor of geology at Pomona and fall in love with the place and its students. Apply for a tenure track position, and to your surprise, get your dream job.

Get hired for a one-year position as visiting assistant professor of geology at Pomona and fall in love with the place and its students. Apply for a tenure track position, and to your surprise, get your dream job. As an expert on the ecosystems and geology of the Cambrian explosion of life forms, travel the world and take part in some of the biggest paleontological discoveries of our time, from Canada to China.

As an expert on the ecosystems and geology of the Cambrian explosion of life forms, travel the world and take part in some of the biggest paleontological discoveries of our time, from Canada to China. Serve as chair of the Geology Department and take leadership roles in college governance. Among other things, help create the position of chair of the faculty and co-chair the Strategic Planning Steering Committee.

Serve as chair of the Geology Department and take leadership roles in college governance. Among other things, help create the position of chair of the faculty and co-chair the Strategic Planning Steering Committee. Though you’re shocked to be asked, agree to lead the College’s academic program as interim dean for one year; then, persuaded by the pleasure of working with the faculty, agree to serve for three years.

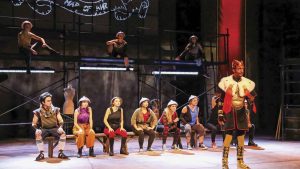

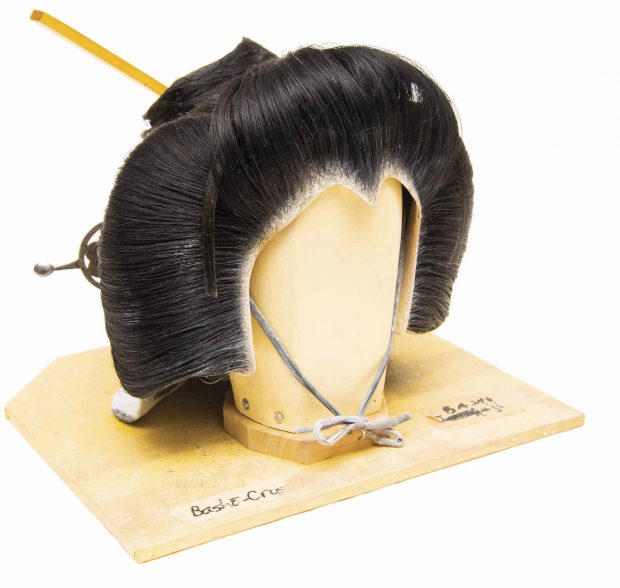

Though you’re shocked to be asked, agree to lead the College’s academic program as interim dean for one year; then, persuaded by the pleasure of working with the faculty, agree to serve for three years. In the early 1960s, the late Professor Leonard Pronko discovered the Japanese art of kabuki while studying theatre in Asia on a Guggenheim Fellowship. He then made history in 1970 as the first non-Japanese person ever accepted to study kabuki at the National Theatre of Japan. Bringing his fascination back to Pomona College, he directed more than 40 kabuki-related productions over the years, ranging from classic plays to original creations. The wig pictured here is one of several that remain from those productions. Below are a few facts about that intriguing Pomona artifact. (For more about Professor Pronko’s life, see

In the early 1960s, the late Professor Leonard Pronko discovered the Japanese art of kabuki while studying theatre in Asia on a Guggenheim Fellowship. He then made history in 1970 as the first non-Japanese person ever accepted to study kabuki at the National Theatre of Japan. Bringing his fascination back to Pomona College, he directed more than 40 kabuki-related productions over the years, ranging from classic plays to original creations. The wig pictured here is one of several that remain from those productions. Below are a few facts about that intriguing Pomona artifact. (For more about Professor Pronko’s life, see