Photo-illustration combining a photo the R/V Roger Revelle at sea and a photo of Roger Revelle ’29 at work on another research vessel many years before.

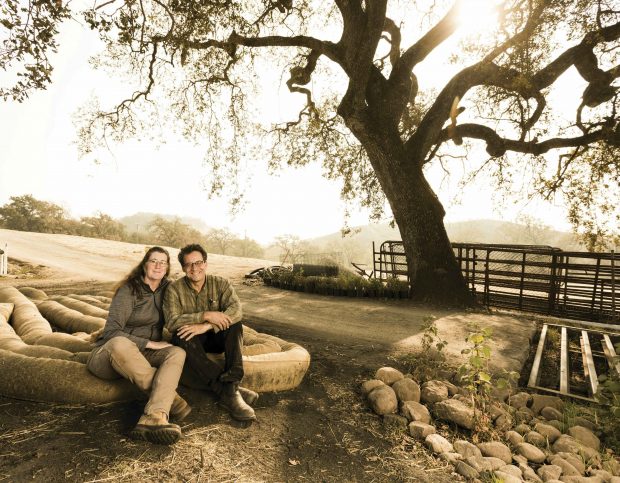

Calm seas and sunny weather greeted the R/V Roger Revelle’s maiden voyage in July 1996 as it traveled south from Mississippi, through the Panama Canal and then to San Diego. On board the 273-foot research vessel—the namesake of climate scientist Roger Revelle ’29—were his wife, Ellen Clark Revelle, and their daughter Mary Ellen Revelle Paci ’57, who shared a cabin and relished the chance to experience firsthand the ship’s first passage.

Revelle collects mud from the bottom of the ocean floor for his research as a Ph.D. student at Scripps Institution of Oceanography.

“It was just a remarkable adventure, and we were both very proud of my dad. Really, it was an honor that I was on that ship,” Revelle Paci says.

Revelle died 27 years ago, but his legacy lives on—and not only in the ship that bears his name. A major figure in the early years of climate science and oceanography, he helped establish both fields and elevated them to the international stage. As the director of Scripps Institution of Oceanography (not affiliated with Pomona’s sister institution, Scripps College), he drew attention to growing levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere that would produce a global warming trend and encouraged other scientists to join him in studying the problem. He also served as science advisor to President Kennedy’s Department of the Interior, testified before congressional committees and was a professor and mentor for future vice president and Nobel laureate Al Gore.

The R/V Revelle today continues to enable the research of climate scientists following in Revelle’s footsteps. The scientists who use it are typically supported by the National Science Foundation, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the Office of Naval Research and even NASA. Owned by the Navy and operated by Scripps, the research vessel spends some 300 days per year at sea, facilitating a wide range of physics, chemistry, biology and ecology involving the oceans and atmosphere.

“The less I see my ship at port, the better,” says Bruce Appelgate, director of ship operations at Scripps. “We hopscotch all over the world,” he says, with brief stops as one researcher unloads their gear, equipment and people and another loads theirs, finally getting a chance for some field research they may have waited years for.

Like the Hubble Space Telescope, the R/V Revelle is popular with scientists. For example, Scripps oceanographer Andrew Lucas ’98 has been on the Revelle many times, and like Revelle himself, he’s a Pomona College grad.

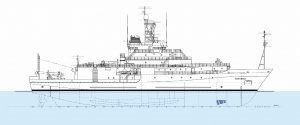

R/V Roger Revelle by the Numbers

BUILT: 1996

LENGTH (FEET): 273

TOP SPEED (KNOTS): 15

DRAFT (FEET): 17

TONNAGE: 3,180

FUEL CAPACITY (GALLONS): 227,500

RANGE (NAUTICAL MILES): 15,000

CREW: 21

SCIENCE BERTHS: 37

LAB AREA (SQUARE FEET): 4,000

“I’ve been studying the southwest monsoon in Southeast Asia,” Lucas says. “Something like 75% of the annual moisture in that region comes from this monsoon weather pattern. It couldn’t get any more important—it allows people to grow food. Failure of the monsoon, such as starting later or not as much rain, means people will starve to death.”

Lucas and his colleagues developed and built technologies to use on the Revelle to map the upper ocean and lower atmosphere at high resolution. They drive the ship to a particular location, such as the Bay of Bengal, and then use scientific equipment on board—especially the ship’s meteorological instruments and the onboard hydrographic Doppler sonar system, which maps ocean velocities up to 1,000 meters below the ship—while deploying dozens of autonomous vehicles, like drone gliders and floaters that move up and down in the seawater.

Such technologies weren’t available, however, when Revelle and his fellow researchers were just getting started, trying to probe the subtlest signatures of climate change decades before its effects could be clearly felt.

“He’d probably be amazed at how much we’re able to simulate now compared to what people were trying back in the 1950s. When you don’t have those kinds of tools, you have to be cleverer to find the measurements that are really going to tell you something important,” says Gavin Schmidt, a climate scientist at NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies and Columbia University in New York. “That generation was exceptional at doing that—pulling things together for relatively simple measurements of a complex system. That’s a real gift.”

Revelle’s scientific talents weren’t evident early on. “He was not a stellar student at Pomona. He was almost kicked out,” says his son, William Revelle ’65, a psychologist at Northwestern University. He spent lots of time working as editor of the Pomona Student Life newspaper at the expense of schoolwork. But then the geologist Alfred “Woody” Woodford saw his potential and encouraged him.

Revelle (right) aboard a research vessel with Harold Sverdrop (center), then director of Scripps Institution of Oceanography.

Revelle eventually got through and graduated. He pursued research at the University of California, Berkeley, and at Scripps, analyzing Pacific Ocean deep-sea sediments. Revelle went on to serve during World War II as an oceanographer in the Navy, where he helped establish the Office of Naval Research, and then he continued his leadership at Scripps. He also helped found the University of California, San Diego, served a term as president of the American Association for the Advancement of Science and became the founding chairman of the first Committee on Climate Change and the Ocean.

While at home, he often talked about oceanography, carbon dioxide levels, population-related issues and science in general. “Our dinner table was like a seminar. My father spoke slowly and thoughtfully,” says Carolyn Revelle, his youngest daughter. Revelle and his wife entertained lots of guests, including scientists from around the world and Nobel Prize winners he was recruiting to UC San Diego.

He also sometimes spoke about nuclear war, including the environmental impacts of radiation, which he had learned about from measurements taken during the atomic bomb tests at Bikini Atoll. Revelle and his colleagues were concerned about how contamination from plutonium and its fission would harm fisheries in the region. Then in the 1950s, he wrote a paper about the ecological effects of atomic wastes at sea — which is again a concern with rising sea levels causing erosion near the coastal San Onofre Nuclear Generating Station north of San Diego.

A portrait of Roger Revelle ’29

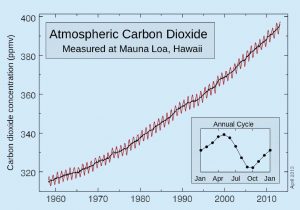

Revelle invited Charles David Keeling to Scripps and supported his work on carefully measuring carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere with an infrared gas analyzer at Mauna Loa Observatory in Hawaii. At the same time, Revelle helped create the International Geophysical Year to promote East-West collaboration on Earth science research, including Keeling’s program. This research led to a record of atmospheric measurements now known as the Keeling Curve (see “Revelle & the Curve” on opposite page), a graph that depicts the relentless rise of carbon dioxide concentrations beyond natural seasonal variation—the “breathing” of the Earth. The measurements showed the concentration to be about 310 parts per million in 1958 and then 320 a few years late; now it’s up to about 410, making the trend a clearly upward curve with teeth.

“Given how important that has become—iconic, even—his role in producing it is really very significant,” Schmidt says. Gore included it in his 2006 documentary, An Inconvenient Truth.

In 1957, Revelle and physicist Hans Suess published a seminal study arguing that growing carbon dioxide emissions produced by human activities — namely, burning fossil fuels — could create a greenhouse effect, gradually warming the planet. They also were the first to show that the ocean surface increasingly resists absorbing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. Revelle and Suess calculated a quantity now referred to as the Revelle factor, which is the change in carbon dioxide in the seawater relative to that of dissolved inorganic carbon. They found it to be about 10, and more recent measurements show that it’s rising, especially at high latitudes such as those in the Southern Ocean, where less carbon can be absorbed and therefore future climate change cannot be so efficiently mitigated.

Revelle’s work on oceans acting as “carbon sinks” also has inspired current debates about geoengineering and climate interventions, including controversial proposals like spraying material into clouds to reflect sunlight into space, or pumping nutrients into oceans to encourage carbon-consuming photosynthesis of marine algae.

Revelle & the Curve

Engraved on the wall of the U.S. National Academy of Sciences, alongside such images as Darwin’s finches and DNA’s double helix, is a steeply curved graph depicting the rising levels of carbon dioxide in our atmosphere. It’s there because the discovery of the rising tide of atmospheric CO2 is considered one of the most important discoveries of our time.

The numbers that generated that graph were produced at a rate of one per hour by a type of infrared spectrophotometer known as a nondispersive infrared sensor, installed at Mauna Loa Observatory, two miles above sea level on the big island of Hawai‘i in 1958. Put in place by a scientist named Charles Keeling, that instrument and others that later replaced it have been cranking out those numbers, hour by hour, right up until today. The graph that they produced is now famous as the Keeling Curve.

As a young chemist at Caltech, Keeling had developed the first reliably precise method of measuring levels of carbon dioxide in atmospheric samples. That brought him to the attention of Roger Revelle ’29, then director of Scripps Institution of Oceanography, who persuaded him to continue his work at Scripps under Revelle’s mentorship.

As one of the founders of the International Geophysical Year (IGY), Revelle also helped arrange for an IGY grant for Keeling to establish a base at Mauna Loa where he could continue his measurements, beginning in 1958. In 1961, Keeling first produced his famous graph.

One of the first to recognize the importance of that curve, Revelle brought it into the classroom when he left Scripps to teach at Harvard. There it first came to the attention of another of his mentees, Al Gore, who would eventually bring the dire significance of that curve to a wider public in his documentary film about climate change, An Inconvenient Truth.

Later, while teaching at Harvard, Revelle raised concerns about issues involving what’s called “climate adaptation” today. Poorer countries, such as Pacific island nations with indigenous populations, don’t have the resources to adapt to climate change the way that wealthy countries like the United States do, yet they are feeling the effects first.

In the final year of his life, however, REVELLE became perhaps the first high-profile victim of vocal climate deniers. Physicist Fred Singer, already notorious for his skepticism about acid rain and ozone depletion, managed to manipulate the 81-year-old Revelle—his family and colleagues argue—into adding his name to a paper playing up uncertainties in climate change science and arguing against taking “drastic action.”

While talking to the American Association for the Advancement of Science about atmospheric and oceanic warming and efforts to reduce them, Revelle noted the wide range in the possible extent of warming in the next century. Afterward, Singer spoke to him about working on an article together, but then Revelle had a heart attack while returning to San Diego. As chronicled in the 2010 book Merchants of Doubt, by historians Naomi Oreskes and Erik Conway, Singer wrote a draft with a similar title to one he had already published, “What to Do About Greenhouse Warming,” but the ailing Revelle was not particularly interested in it. When he read it he crossed out “less than one degree” Celsius of warming, and wrote in the margins “one to three degrees”—clearly beyond natural climate variability—but this was never incorporated in the published paper, which came out with his and Singer’s names on it after Revelle died.

Carolyn Revelle wrote an opinion piece on behalf of the family in The Washington Post, saying her father had not changed his views. There were significant uncertainties at the time, and like most scientists, he didn’t want to overstate the threat of global warming. But he clearly considered the warming trend to be a dangerous one.

“He was dying of heart failure, and I feel that he was vulnerable. It was a very unfortunate experience, but I do not think it indicates that he changed his mind on global warming, which was what the climate change deniers were saying,” she says.

Revelle’s secretary Christa Beran, his graduate student and teaching assistant Justin Lancaster and colleagues like oceanographer Walter Munk also sought to defend him.

“You had what was an insidious example of what I would call a lack of ethics in science and the use of scientists as hired guns by the industry,” Lancaster says. “It was very cleverly done; they pulled the wool over Roger’s eyes. I discovered it too late to intercede. I didn’t have the clout to get the right attention to this, and Roger had died. All I could do was make it as public as possible.”

He points out the ways Singer and a handful of other scientists have been supported by the fossil fuel industry, noting that Singer’s Science & Environmental Policy Project, a research and advocacy group, was financed by ExxonMobil and other private sources. Singer had also earlier consulted for ExxonMobil and other major oil companies.

Even decades later, Singer and a few other figures remained “contrarians for hire,” Schmidt says. Documents leaked to DeSmogBlog in 2012 showed that Singer and a few others had been receiving monthly funding from the Heartland Institute, a free-market think tank financed by billionaire Charles Koch that has promoted climate skepticism. The Heartland Institute continues to try to influence climate policy through connections to President Trump’s Environmental Protection Agency.

The real purpose of Singer’s paper, Lancaster believes, was to undercut Al Gore while he was running for president in 1992. Revelle had taught Gore at Harvard and had introduced him to the scientific and political challenges of climate change. Gore’s campaign focused on environmental and climate issues, and Singer’s paper came up in a question at the vice presidential debate.

Singer, now 94, responded in an email, saying that ExxonMobil and the Heartland Institute do not support him and have not influenced the positions he has taken. He also prefers to call himself a climate skeptic, not a denier.

Since Revelle’s death, climate change has arguably become even more politicized in the U.S. According to Pew and Gallup polls, over the past decade, the chasm between the views of Republicans and Democrats has widened: There is now at least a 30 percent gap between members of the two parties on whether climate change is occurring, whether it’s driven by human activities and whether addressing it should be a top priority of policymakers. That gap has kept growing even as the consensus among climate scientists that global warming is real and anthropogenic has topped 97 percent. And climate change has yet to make another appearance at a presidential (or vice presidential) debate.

The U.S. and the international community have made limited progress in mitigating climate change, and climate deniers remain as vociferous and influential as before. While it’s easy to despair at the thought of possible climate disasters to come if we reach an average warming of 2 degrees Celsius or more, Revelle likely would emphasize hope about humans’ abilities to adapt. “I know exactly what Roger would say: ‘There’s no future in pessimism.’ This was his whole viewpoint on the climate change problem,” Lancaster says.

In the meantime, scientists continue to collect data and conduct research about climate change and its myriad effects around the world. The Revelle just completed a trip to Tahiti and New Zealand, with scientists on board probing ocean chemistry, including spotting trace amounts of metals and isotopes in seawater. It’s due for its mid-life service and maintenance in dry dock this year, after which the research ship will continue its scientific journeys for two decades or more.

The Revelle clan in 1964: Front row: Christopher Paci, Ellen Clark Revelle, Roger Revelle ’29, Holly Shumway and Carolyn Shumway. Back row: Stefano Paci in the arms of his father Dr. Piero Paci, Mary Paci ’57 with young Mark Roger Shumway in front of her, George Shumway, Anne Revelle Shumway, Bill Revelle ’65, Eleanor McNown ’64 (later Revelle), Gary Hufbauer, Carolyn Revelle Hufbauer and Loren Shumway.

“Jim Kauahikaua, U.S. Geological Survey’s Hawaiian Volcano Observatory. I’ll do a quick summary of what’s happening. Vents eight and 16 have reactivated. Twenty-two and 13 are still the main southbound channels going into the two ocean entries, though those have been quite weak today …”

“Jim Kauahikaua, U.S. Geological Survey’s Hawaiian Volcano Observatory. I’ll do a quick summary of what’s happening. Vents eight and 16 have reactivated. Twenty-two and 13 are still the main southbound channels going into the two ocean entries, though those have been quite weak today …” But the main thing that Kauahikaua says tried his patience during those long weeks was the bureaucratic conceit of some of the early incident management teams sent in by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), which used the emergency as a training exercise. “None of them had Hawai‘i experience or eruption experience, so—for example, safety out in the field. All of a sudden, we had these people from God knows where, Georgia maybe, telling us what was safe and what was not safe. And that rubbed a lot of people the wrong way.”

But the main thing that Kauahikaua says tried his patience during those long weeks was the bureaucratic conceit of some of the early incident management teams sent in by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), which used the emergency as a training exercise. “None of them had Hawai‘i experience or eruption experience, so—for example, safety out in the field. All of a sudden, we had these people from God knows where, Georgia maybe, telling us what was safe and what was not safe. And that rubbed a lot of people the wrong way.”

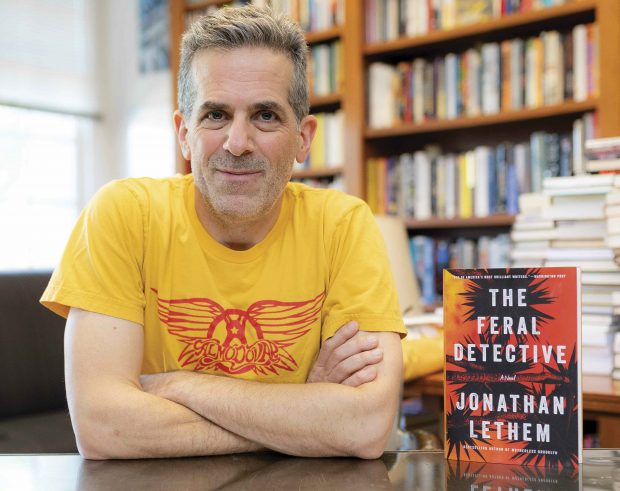

The motif of feral children was in critically acclaimed novelist Pomona College Professor Jonathan Lethem’s index of writing ideas for many years. There was the concept of urban feral children in New York City. Archetypal fictional characters like Tarzan and Mowgli. Real-life stories of feral children. A Pomona College course he designed on animals in literature had a portion devoted to the idea of the feral. All things feral fascinated him. So, a feral child of a different kind was born: the book The Feral Detective. This wild detective-book child was local-born, with the story set in the surrounding Inland Empire, the mountains and the desert region (what Lethem calls “the scruffier east”). He took the feral even farther, exploring desert-dwelling communes and creating two off-the-grid communes, the Rabbits and the Bears, that he writes about in his book.

The motif of feral children was in critically acclaimed novelist Pomona College Professor Jonathan Lethem’s index of writing ideas for many years. There was the concept of urban feral children in New York City. Archetypal fictional characters like Tarzan and Mowgli. Real-life stories of feral children. A Pomona College course he designed on animals in literature had a portion devoted to the idea of the feral. All things feral fascinated him. So, a feral child of a different kind was born: the book The Feral Detective. This wild detective-book child was local-born, with the story set in the surrounding Inland Empire, the mountains and the desert region (what Lethem calls “the scruffier east”). He took the feral even farther, exploring desert-dwelling communes and creating two off-the-grid communes, the Rabbits and the Bears, that he writes about in his book.

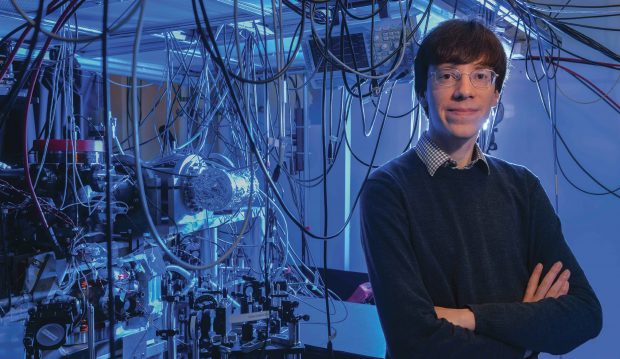

Grow up in Seattle, Washington, the son of two science professors, and get your first electricity set at the age of 5. Become fascinated with building little robots (including a mini Mars rover) with Lego Mindstorms from the age of 8 on.

Grow up in Seattle, Washington, the son of two science professors, and get your first electricity set at the age of 5. Become fascinated with building little robots (including a mini Mars rover) with Lego Mindstorms from the age of 8 on. Start playing the cello at age 10 and keep playing through middle school and high school. Do so in part for the same reason you’re attracted to research—because it allows you to work alongside others while pursuing long-term goals and building incremental skills.

Start playing the cello at age 10 and keep playing through middle school and high school. Do so in part for the same reason you’re attracted to research—because it allows you to work alongside others while pursuing long-term goals and building incremental skills. In middle school, attend a summer program on rockets and robotics, where you become intrigued by the mathematics of energy and momentum. Take a particular interest in air resistance and decide you want to do something about it for your next science project.

In middle school, attend a summer program on rockets and robotics, where you become intrigued by the mathematics of energy and momentum. Take a particular interest in air resistance and decide you want to do something about it for your next science project. Join the Frisbee team at school and become fascinated with the physics of flying disks. Teach yourself to use video tracking techniques in order to win the eighth-grade science fair with a project examining the aerodynamics of a spinning Frisbee.

Join the Frisbee team at school and become fascinated with the physics of flying disks. Teach yourself to use video tracking techniques in order to win the eighth-grade science fair with a project examining the aerodynamics of a spinning Frisbee. In high school, branch out into nonscientific disciplines with classes in philosophy, comparative government and politics. Realize you want to go to a college where you can do science while also exploring other interests.

In high school, branch out into nonscientific disciplines with classes in philosophy, comparative government and politics. Realize you want to go to a college where you can do science while also exploring other interests. Pick Pomona because it checks all your boxes, including a broad curriculum, strong programs in math and physics and the chance to do research. An opening for a cellist in the orchestra and appealing food options seal the deal.

Pick Pomona because it checks all your boxes, including a broad curriculum, strong programs in math and physics and the chance to do research. An opening for a cellist in the orchestra and appealing food options seal the deal. As a first-year, get your first taste of college physics in Whitaker’s Spacetime, Quanta and Entropy class. Get an invitation to work in Whitaker’s lab, in part because of your experience with video tracking and the aerodynamics of rotating bodies from your Frisbee project.

As a first-year, get your first taste of college physics in Whitaker’s Spacetime, Quanta and Entropy class. Get an invitation to work in Whitaker’s lab, in part because of your experience with video tracking and the aerodynamics of rotating bodies from your Frisbee project. After your first year, do a summer research project at the University of Maryland, College Park, in which you use computer code to track the location of sand grains in three dimensions. Bring that code back to Pomona to track flying, spinning seeds.

After your first year, do a summer research project at the University of Maryland, College Park, in which you use computer code to track the location of sand grains in three dimensions. Bring that code back to Pomona to track flying, spinning seeds. As part of Whitaker’s lab team, gather a lot of data during your sophomore year and spend your junior year analyzing it for a paper of which you’re listed as an author, published in the Journal of the Royal Society Interface. Expand upon this for your senior thesis.

As part of Whitaker’s lab team, gather a lot of data during your sophomore year and spend your junior year analyzing it for a paper of which you’re listed as an author, published in the Journal of the Royal Society Interface. Expand upon this for your senior thesis. Learn that you are one of three finalists in your category for the Apker Award. Give a nerve-wracking 30-minute presentation before the selection committee in Washington, D.C. Learn after starting at Stanford that you won.

Learn that you are one of three finalists in your category for the Apker Award. Give a nerve-wracking 30-minute presentation before the selection committee in Washington, D.C. Learn after starting at Stanford that you won.

For years I’ve wanted to publish a retrospective about Roger Revelle ’29, the oceanographer and climate scientist widely credited with pushing climate change into the consciousness of the nation and the world. So I’m delighted, finally, to include Ramin Skibba’s beautiful story about the scientist’s life and work in this issue. But as I edited the piece, I was troubled to learn that Revelle was also one of the very first targets of climate deniers—and remains a target to this day.

For years I’ve wanted to publish a retrospective about Roger Revelle ’29, the oceanographer and climate scientist widely credited with pushing climate change into the consciousness of the nation and the world. So I’m delighted, finally, to include Ramin Skibba’s beautiful story about the scientist’s life and work in this issue. But as I edited the piece, I was troubled to learn that Revelle was also one of the very first targets of climate deniers—and remains a target to this day.