Around the World with U.S. Ambassador to Rwanda Eric Kneedler ’95

Photo of Eric Kneedler ’95 (courtesy of the U.S. Embassy Kigali)

In March of 2023, as C-SPAN cameras rolled, Eric Kneedler ’95 sat at a long table in a high-ceilinged room inside the Dirksen Senate Office Building, mentally reviewing his talking points. Across the room, Senator Cory Booker ruffled through some notes, flanked by other members of the Foreign Relations Committee. Behind Eric, the audience, which included his wife, Kristin, sat silently; to his left and right, four other nominees waited.

For Kneedler, three decades in the Foreign Service had led to this moment: the nomination hearing for his appointment as the U.S. Ambassador to Rwanda. The position represents the pinnacle of a Foreign Service Officer’s career, one only a tiny percentage of officers ever achieve. To reach this point, Kneedler had lived in six countries, learned four languages, and met with countless domestic and foreign dignitaries. Along the way, he’d forged an intimate relationship with jet lag; managed the challenges of itinerant family life; and become accustomed to being on call at all hours.

At left, Ambassador Kneedler engages with Rwandan youth through U.S. sports diplomacy programs. Photo courtesy of the U.S. Embassy Kigali. On the right, Kneedler treks through Volcanoes National Park and encounters a member of the Lisanga mountain gorilla family. Photo courtesy of the U.S. Embassy Kigali.

More recently, though, he’d been in limbo against the backdrop of a nomination logjam. Confirmations had become scarce. So he’d drilled and re-drilled the particulars of the political situation in Rwanda—the conflict with the Democratic Republic of the Congo, human rights concerns, U.S. business interests—preparing for hundreds of potential questions he might receive from the Committee.

In short order, the proceedings began. Soon enough, Booker called upon Kneedler for his testimony. Eric thanked the Senator and the Committee, looked up from his notes, and began.

Before we go any further—into the particulars of Kneedler’s diplomatic work, or how he ended up in Rwanda—let’s return first to the roots of his career, on the Pomona campus in the early 1990s. (As a fellow member of the Class of ’95, and now long-time friend, this is also when I first met Kneedler.)

Eric had arrived in Claremont from Lancaster, Pa., the son of Francophile parents who’d instilled in him a curiosity about the broader world. A member of the Model UN in high school, he gravitated to the political science department at Pomona, majoring in government. On campus, he played a year of basketball, honed his French, connected with mentors like Lorn Foster, and, in his junior year, studied abroad in Strasbourg, France, a catalyzing experience. There, he met staff at the local consulate, immersed himself in the culture, and, for the first time, heard of something called the Foreign Service. That summer, he secured an unpaid internship on Capitol Hill. From the outside, his path seemed set.

Then: a detour. The summer after graduation, Kneedler took a job in construction and then, on a whim, as a door-to-door vacuum cleaner salesman. Though, as Eric would stress to potential customers, the Kirby was no humble vacuum but rather a “cleaning system,” one with an internal fan designed with the help of NASA (yes, that NASA, he’d add).

Now, for most people the idea of charming your way into someone’s house, connecting on a personal level, and then convincing them to spend $1,400 on a vacuum would seem near-impossible. Eric? In his first month, he sold 22. A month later, he’d ascended to top salesman in the Eastern States Division; a month after that, he was honored at a banquet in New Orleans as the New Kirby Salesman of the Year.

In an alternate universe, Kneedler might have joined the Mount Rushmore of Kirby salesmen. Unfortunately for the company—but fortunately for the State Department—he left after only a few months, having earned enough to fund his next endeavor: a graduate degree at the School of Advanced International Studies at Johns Hopkins. And while Kirby has long since been eclipsed on his resume, the core skills—connection, persistence, persuasion—remain. “Diplomacy is sales,” Kneedler says. “You’re selling your country and what your country has to offer.”

Eric’s time at Johns Hopkins crystallized an interest in working abroad. So, in 1998, he headed to Rosslyn, Virginia, to complete the Foreign Service exam, the second half of which consists of in-person interviews and exercises meant to measure collaboration and consensus-building—“how well you can play in the sandbox with others,” as Kneedler puts it. He arrived nervous but prepared. “And I remember on the way into the exam, I was in the elevator and there’s a guy who had just entered the building, so I held the elevator door for him,” he says. Kneedler then went on with the examination process, sitting for multiple interviews over the course of the day. “At the end, a guy walks into the door, congratulates me on passing and says, ‘By the way, thanks again for holding the elevator door for me.’” The lesson stuck: little things matter.

Kneedler (center) hosting a delegation of representatives from Howard University in the Rwandan capital Kigali. Photo courtesy of the U.S. Embassy Kigali.

The following year, he caught a flight to Hong Kong for his first posting.

In popular culture, on shows like The Diplomat, Foreign Service Officers are often glamorized. The reality is more complicated.

In all, over 15,000 officers are spread across 270 embassies in 170-plus countries, divided up into five career tracks, or “cones,” which include consular, public diplomacy, and political affairs (Kneedler’s area). The career path is unforgiving, an up-or-out system where you must be promoted every few years or leave. Since officers change posts every two to four years, adaptability is essential; just when you become comfortable in one situation, you’re parachuted into another.

In Eric’s case, he became adept at cramming—both on local politics and customs and languages. He took six months of Cantonese before touching down in Hong Kong, a year of Thai prior to Bangkok, a year of Indonesian before landing in Jakarta.

Ask Eric exactly what he “does” as an FSO and he’ll tell you that depends. Early in his career, he helped American tourists who’d lost passports and conducted visa interviews (including, he notes, for Jackie Chan). At other times, he wrote “cables,” formal, encrypted messages concerning internal policy, or sat in on meetings. Twice, he supported then-Senator Marco Rubio’s overseas visits, in Manila and Nairobi; he also helped host former President Bill Clinton’s presidential delegation to Rwanda, talking over dinner. That’s the nature of the job—American diplomats swear an oath to defend the Constitution, and Eric’s 27+ year career speaks to the nonpartisan nature of the job, split as it has been evenly across Republican and Democratic administrations.

At times, the work has been high-stakes. In March 2008, working with local Thai authorities and U.S. agents, Kneedler was part of the successful effort to apprehend Viktor Bout, the Russian arms trafficker known as the “Merchant of Death.” In Manila, his Embassy team helped strengthen security ties between the U.S. and the Philippines at a crucial time, as the shadow of a rising China loomed.

Throughout, he’s also managed what he calls the biggest challenge of the position: family logistics. In the Kneedlers’ case, Kristin, herself a talented and successful diplomat, also joined the Foreign Service. This had advantages. It also meant being “more thoughtful and deliberate” about postings, as Eric puts it. So they sought out locations with good jobs for each of them, as well as the right environment to raise their two children, son Toren and daughter Ella (currently a sophomore at Pitzer and psychology major).

By 2019, Eric had ascended to Deputy Chief of Mission—essentially, second in command—in Nairobi, Kenya, managing the embassy during the COVID crisis and working closely towards the end of his tenure there with Ambassador Meg Whitman, the former CEO of Hewlett-Packard. Like roughly one-third of Ambassadors, Whitman was a political appointee, chosen by the sitting President. Career FSOs take a far less-direct route; the fraction who rise to become ambassadors do so only after decades of meritorious service.

Ambassador Kneedler receives the first shipment of Rwandan tungsten to the United States in his home state of Pennsylvania—a significant commercial achievement for the American people. Photo courtesy of the U.S. Embassy Kigali.

Which brings us back to March of 2023, in the Senate Building, as Kneedler answered questions from Booker and others, touching on the challenges that awaited in Rwanda: human rights issues, defusing tensions with the DRC, and policy around rare earth metals. “If confirmed,” he said, “I will work tirelessly to promote freedom of expression, democratic governance, and access to justice.”

Then, he waited for the Senate vote. Months passed. No movement.

Finally, on the night of July 27th, the Senate held a voice vote on Kneedler and other candidates. The news traveled quickly: he’d made the cut.

By late fall, he’d settled into the capital city of Kigali with Kristin and their two yellow Labradors retrievers, Pi and Steel (close readers will note the connection to Kneedler’s lifelong allegiance to Pittsburgh sports). As Ambassador, his days filled with meetings, press conferences, and dinners.

Since then, he’s faced an array of challenges. He ran point as global attention turned to the country in April of 2024 for the 30th anniversary commemoration of the Rwandan genocide. He organized the U.S. response when a deadly outbreak of Marburg disease required immediate action. And, throughout, he’s supported an unprecedented U.S. government-led effort to broker an end to decades of conflict in eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo.

For Kneedler and his team, the goal has been to create opportunities for American businesses and promote regional stability while also pressing, however delicately, on areas where Washington and Kigali do not always see eye-to-eye—a balancing act that rewards equal parts candor and tact.

What makes for a successful diplomat?

Ask Eric about his career and he invariably deflects credit, citing luck, circumstance, and numerous mentors, from a high school Model U.N. teacher to Kristie Kenney, former Ambassador in the Philippines, Ecuador, and Thailand.

However, ask those familiar with Eric’s career and they focus not on specific accomplishments—of which no shortage exist—but some rather human skills. Take Patrick Cottrell, who attended Johns Hopkins with Eric, served in the State Department, and now chairs the Political Science department at Linfield University (and whose two daughters, Sydney ’26 and Elsa ’28, are both Sagehens). He notes Kneedler’s curiosity—“he’s a lifelong learner”—and social intelligence.

“In his position, you need to be willing to understand a very complex situation from different vantage points and be empathetic but removed enough to create common space for agreement,” says Cottrell. “Eric has a perfect temperament for that because he’s a great listener and is able to drill down to the essence of people’s motivations and is able to frame and align issues in ways for people you think would have very different preferences.”

Mark Stroh, the current Deputy Chief of Mission in Copenhagen, has known Kneedler for three decades. He credits Eric with being both mentor and role model (“I ask myself, ‘What would Eric do?’” says Stroh). Stroh highlights a different trait, one many unsuspecting owners of Kirbys might agree with: “You can’t say no to Eric.”

Part of that is forging connections. Sometimes it’s through small things—for example, Eric has seemingly memorized every collegiate mascot from DIII to DI so that, upon meeting someone who went to, say, Murray State, he can say, “Ah, the Racers.” Other times, it’s via empathy: the ability, as he puts it, “to ask questions, to listen to the answers, to respond in real time, understand what the speaker is saying to you—both directly and in terms of body language—and redirect the conversation as needed based on those social-emotional cues.” Really, though, he says it comes down to something deceptively simple: “The ability to listen and learn.” He pauses. “It’s surprising how few people actually listen.”

The 13 Dimensions

- Composure

- Cultural Adaptability

- Experience and Motivation

- Information Integration and Analysis

- Initiative and Leadership

- Judgment

- Objectivity and Integrity

- Oral Communication

- Planning and Organizing

- Quantitative Analysis

- Resourcefulness

- Working With Others

- Written Communication

It brings to mind what the Foreign Service calls “the 13 Dimensions,” the list of human qualities it looks for in candidates—traits like judgment, cultural adaptability, and working with others. In an age of AI, remote work, and groupthink, developing and honing these skills may be more challenging than ever. And, indeed, to read the list of Dimensions is to notice that they bear an uncanny resemblance to the core tenets of something else: a liberal arts education.

It’s something Kneedler notes himself: that the same habits he developed on Pomona’s campus—the same instincts that once helped him sell a $1,400 vacuum—now help him sell something far more valuable: the idea of America abroad.

A Closer Look at Rwanda

Rwanda and its capital, Kigali, are bordered by Uganda (north), Tanzania (east), Burundi (south), and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (west).

Clean & getting cleaner: With President Paul Kagame’s ambitions to make Rwanda the “Singapore of Africa,” the country is exceptionally litter-free, in part because citizens perform three hours of community service on the last Saturday of every month (Umuganda). In 2008 it was also one of the first nations to ban single-use plastic bags and bottles.

“Land of a thousand hills:” Rwanda’s common nickname stems from the fact that most of its land is between 3,000 and 15,000 feet above sea level. Its Central Plateau region is full of valleys and hills that form the backdrop of the majority of Rwanda’s towns and villages. The country also shares a mountain range with Uganda and the Congo that include the 8 “Virunga Volcanoes.”

Irrevocably transformed by the 1994 genocide: With a death toll of somewhere between 800,000 and 1 million people, there’s no denying the destabilizing effect of the 1994 genocide on the country. Rwanda’s population of roughly 6 million substantially shifted to be roughly 60 to 70 percent female, with most women having not been raised expecting to have professional careers.

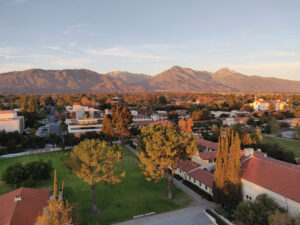

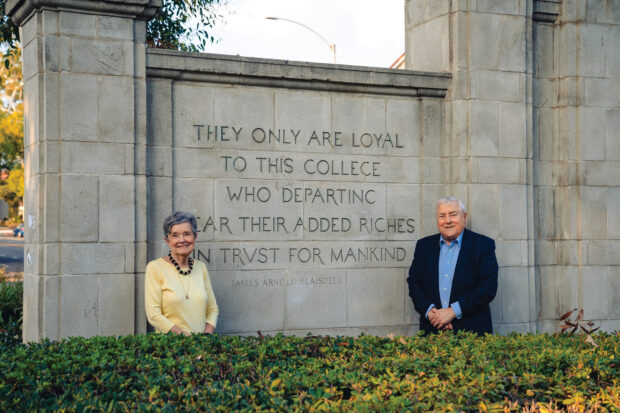

A stone’s throw from a red sandstone hunk on which Sagehens of the past carved their class numerals and motto, “Not to live but to live well,” in Greek, Sagehens of the present and future gathered to celebrate their beloved Pomona College’s founding.

A stone’s throw from a red sandstone hunk on which Sagehens of the past carved their class numerals and motto, “Not to live but to live well,” in Greek, Sagehens of the present and future gathered to celebrate their beloved Pomona College’s founding. “Having a day where we think about where we’ve been helps motivate [us on] this shared path we’re taking on together,” said Michael Steinberger, associate professor of economics and chair of the department. “I particularly appreciate that the events today bring together staff, faculty and students to say that we are together in this incredibly important mission.”

“Having a day where we think about where we’ve been helps motivate [us on] this shared path we’re taking on together,” said Michael Steinberger, associate professor of economics and chair of the department. “I particularly appreciate that the events today bring together staff, faculty and students to say that we are together in this incredibly important mission.”