Meghana Rao ’16

“My experience with Hinduism has a lot to do with community, and the stories within that community. So one way that I express and experience my faith is through dance. I started learning kathak, an Indian classical dance, when I was about 7. It used to be a temple dance, and you would dance it to devotional songs. I don’t know if most people think of dance as a religious experience, but a lot of those devotional songs are very personal for me, so dance has been a very helpful tool to keep me connected to my faith. It’s my way of sharing my culture and my faith with other people.

“Back at home, my religious experience was very community-related. My family would tell the old stories. That community has been a little harder to find here. There is a Hindu community, but it’s such a varied and diverse community that those aspects don’t necessarily come up as much. That’s not to say I don’t connect with people here—I just connect with them in other ways, and my faith has been more of an internal, personal experience. I imagine it’s similar for a lot of people who come here. You meet all these different people, and the ways that you connect are not necessarily through your faith.

“At home, every morning my sister and I would just sit and say this chant called the Gayatri Mantra, which you’re supposed to say nine times every morning. It’s about greeting the sun and accepting the knowledge that it gives you. Here, it just didn’t seem like the space to do that. If you have a roommate, for example, she may sleep late and you don’t want to wake her up. So that’s become an internal thing for me. When I see the sun, I think about it, but I don’t physically chant every morning. That’s an example of how it was more of a communal activity for me at home, whereas here it’s an individual thing that I say to myself. I don’t want to impose my faith on other people. It is a personal thing, and I’m OK with that.

“A lot of Hindusim is kind of a philosophy about life. It’s an outlook on how life should be lived. It’s not necessarily tied to a higher power. There’s freedom for you to shape your own philosophy and views on life within the culture and within the faith. The creation myths and things like that, I take as myths. I don’t necessarily take them as true, and that’s a personal choice. So for me there hasn’t really been that conflict between faith and academics, because I think of it in more of a symbolic sense.

“Every night before I go to bed I say prayers. In some ways, it’s more like a habit than something intentional, but I just can’t go to sleep until I’ve said them, even if it’s just kind of whispering them to myself. I think it’s kind of a connection to home.”

Jose Ruiz ’16

“My parents are from Mexico and they grew up Catholic. It’s ingrained in the culture. So just picking that up as I grew up at home, it became a part of me as well. In high school I really got curious about the religion itself, and the morals it teaches and the lessons that Catholicism has to offer. So I spent a lot of my free time just kind of exploring the Bible, exploring religious texts, spending time with youth groups at church.

“I think just coming to campus, you get this perception that there’s no presence of religion here, or that it’s kind of uncomfortable to talk openly about your religious beliefs. But as you spend more and more time here and talk to more and more people, you do find a sense of community, people who will relate to you on a religious basis. At the same time, you also end up talking to students who challenge your beliefs in terms of what your particular church has done in the past—different scandals, different wars, different administrative events that reflect badly on your religion. But I think at the end of it all, it’s definitely very constructive to be able to listen to some of those concerns but still to be able to practice your religion, so that you can help to prevent those things from happening again in the future.

“I’ve met a lot of students here who are Jewish, a couple who are Hindu, and a lot of students who are of the Protestant or evangelical faiths. So they’re always very interesting, in that a lot of our beliefs are very similar—like when you’re talking about straight-up morals or how you act with other people. Obviously there are nuances in how different religious ceremonies are held—all the history that goes behind it—but I’ve definitely been able to talk to people of different faith backgrounds and help my faith grow because of that.

“Religion evolves over time, just depending on the experiences that you go through in your life, so I guess coming to college in itself can be a way for you to strengthen your religious beliefs and anchor yourself to the beliefs and the morals that are important to you. A lot of students come here and they take whatever opportunity they can get to let go of their religion—because it was imposed on them by their parents or it just didn’t feel right or they want to experiment with other types of belief systems—and so I think in a sense that’s a good way for us to mature and kind of figure ourselves out better.

“Just being challenged about my beliefs and being able to talk to other people about their beliefs and religious experiences, I was able to learn from those and strengthen my own belief in the Catholic Church and how it helps me get through life.”

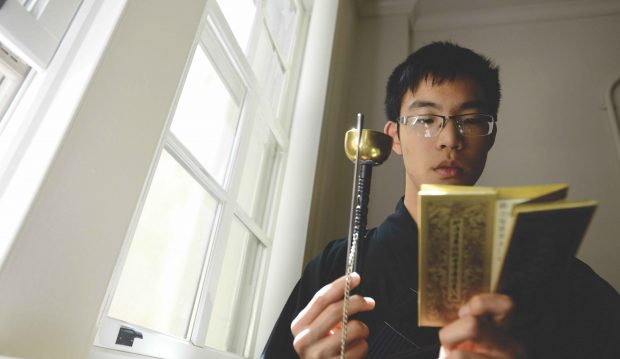

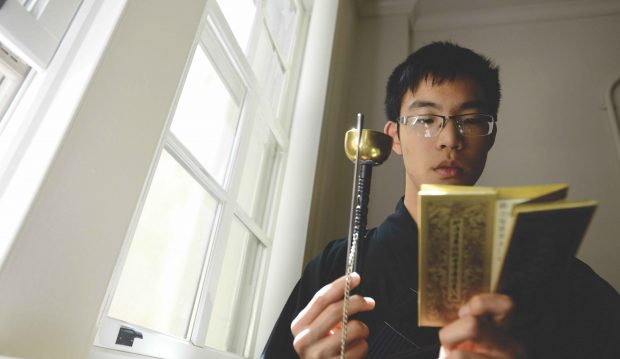

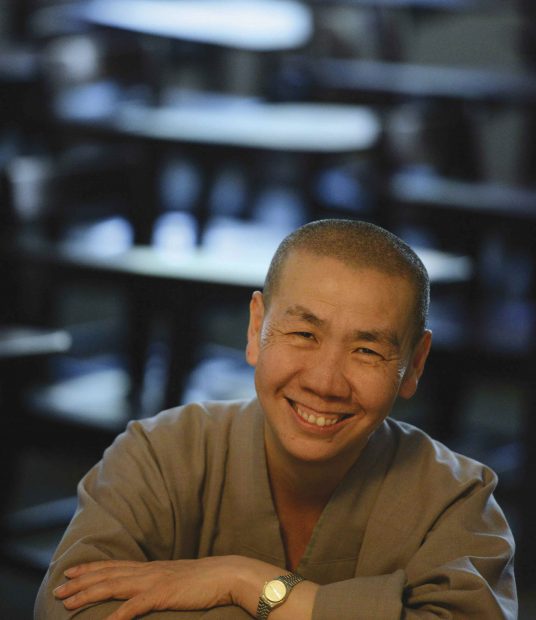

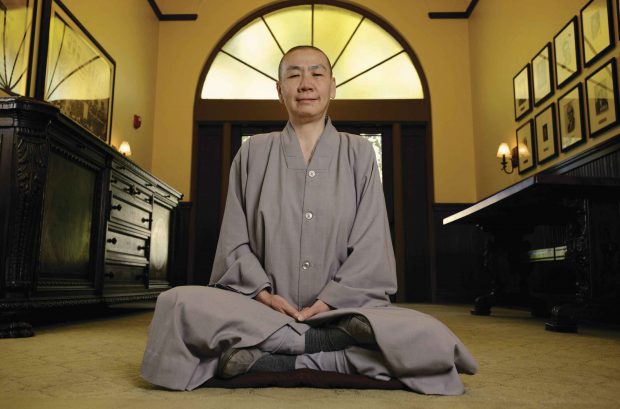

Andrew Nguy ’19

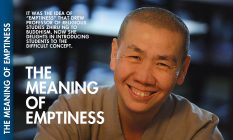

“It’s a story that a lot of young Buddhists share. Someone dies, and because of the funeral rites, there is some sort of religion involved, and Buddhism happened to be the one for my grandma, so her funeral was really where things started for me, and it’s just grown from there.

“My daily routine has shifted over the course of the school year. The first semester I was pretty good, waking up early. I have an 8 a.m. class almost every day, so I would wake up at 6, brush my teeth, get some homework done if I needed to and spend about a half hour chanting the Universal Gate chapter of the Lotus Sutra for its emphasis on compassion and meditating before anybody else was up. Since then, it’s gone from a morning routine to more of a nightly routine. Since now I have more time in the evening, I started doing that—same routine, half an hour or so, but more in the evening than in the morning. And then of course, these past few weeks, with finals coming up, it’s gone from half an hour to 15 minutes to 10 minutes, to ‘Oops, I forgot today. I’ll try again tomorrow.’ That’s the life of a student.

“You won’t see me meditating in class, but the things in Buddhism show up almost everywhere in life, and I can spot it now after being Buddhist for a few years. I can see how conflicts come about. And how, if I get angry as a response to that conflict, it usually only gets worse from there. Realizing that and being able to stop myself before impulse takes over, I’m able to keep the situation a bit calmer and more conducive to actually resolving an issue.

“Being a student, it’s hard to have time in general, and time for what most people think is sitting around doing nothing is even harder. So my compromise is I do a lot of walking meditation when I’m on my way to class and in between classes. Instead of walking to class with a friend, having a nice chat about who-knows-what, I can walk and just kind of focus on my breath, focus on my footsteps as I’m walking, and just be mindful about what I’m doing. Another method I use is recitation. I use the name of Avalokite´svara Bodhisattva, the main figure in the Universal Gate chapter, as a point of focus. Concentrating on the syllables of the name and the compassion it’s associated with, I can use it as my meditation anywhere, even when I’m waiting in line for lunch.

“The purpose of it is more to be able to observe and understand the mind—which might have something to do with my being a psych major—but understanding the mind in a different context. I think the benefits of meditation show up in a lot of ways. If you were to have met me four or five years ago, before I really learned much about Buddhism, I was really impulsive and—I’m not going to lie—I still am sometimes. But meditation has helped me recognize the patterns and my habits. When I’m about to make a rash decision, it kind of pulls me back and says, ‘Stop and think about that first.’”

Ilana Cohen ’16

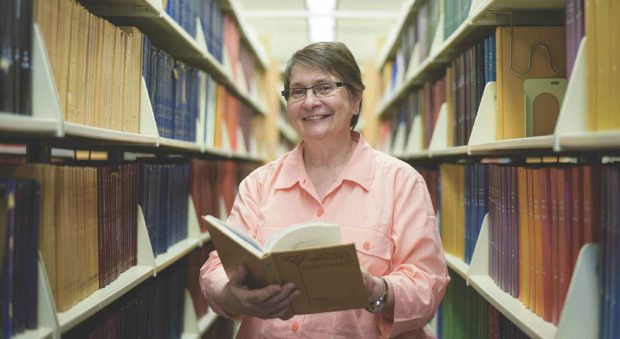

“This is not unique to Judaism, but the time and the cycle are very important. So for us, it’s Friday night through the day of Saturday and observing that as Shabbat in some way. Here, that has meant being at Hillel on Friday nights, pretty regularly. A lot of times, that experience would start for me at about 11 o’clock on Friday when we would pick up the food from the dining halls and bring it over here to the McAlister Center and start cooking for the people who were coming to Shabbat dinner that night. Then we would get the space ready, and often—not every week, but often—I would lead services here in the library. That, for me, was a process of recapturing the Shabbat experience of my synagogue, growing up. Then we would all do dinner together.

“There are many prayers in Judaism that you can’t say unless you have a minyan of people. You wouldn’t say them unless you have that quorum, and there are lots of different reasons why that might be true, but my favorite that I’ve heard is that it’s not that you need 10 voices so that God can hear you—it’s because then somebody does hear you. There are people around you to make the prayer work, because now there are people who know that you’ve said that prayer and support you in doing that. So any time that I’m questioning—well, why am I doing this in a language I don’t really understand?—I know that this is the way to build a community that will be supportive to me.

“So community is very important to me, and the music is also very important, and the fact that it is my history, and it almost wasn’t. My grandmother came out of Austria on the Kindertransport. It’s never why I’ve started a new Jewish practice, but there are always moments where I think, ‘This is just my family’s history.’

“Personally, I almost never use the word ‘faith.’ So when I was thinking about coming here, I was thinking, ‘How am I going to answer these questions?’ I see how it’s a word that broadly allows for anybody’s religious experience, but I think of its association with ‘blind faith,’ and believing or trusting. For me, the religious experience is much more about practice and about learning. Most importantly, from the time I was very little, any participation in Jewish practice was my choice.

Ideologically, nothing I’ve learned or been taught in college is in conflict with my understanding of Judaism, and I didn’t expect it to be. I took a Religious Studies class my first semester, and that was the opposite of a conflict. And I would have done more, but I think I prefer studying it in the religious context, and knowing that I don’t have to get that while I’m in college, because Torah study will be as large a part of my future participation in the Jewish community as religious services.”

Jordan Shaheen ’17

“I’m a big proponent of the war-room theory, which is that you fight all your battles in prayer, not in person. So I kind of get everything I need to get out in the morning in prayer, and then I know I’ve got something there that will get me through the day, until I recharge the next morning.

“I had a church back home that I still go to occasionally. I knew I wanted faith in my life and I wanted a relationship with God, but I’d never really figured out a way to do it. I struggled for years, always reading, always learning about it. There were times when I had atheistic tendencies, times when I wanted to be all-in but didn’t know how to be all-in. Here at school, I finally found a place in the church and was able to really blossom in that role. Now I’m looking at going to divinity school and getting a doctorate of theology and going into the ministry. The thing I love about the Presbyterian Church most is that most ministers have doctorates, so it’s more of an academic denomination, which I’ve come to really appreciate.

“I don’t go out evangelizing—I don’t talk about it at all unless people come to me with questions. It’s something that’s very important to me, and I’m more than happy to talk about it, but I think it’s one of those things where people have to come to you with questions, or else it’s not going to be a meaningful conversation. So I kind of keep to myself, but I think there are a lot more people here for whom religion is important than will say so. It’s kind of an underground group. I know that sounds funny, but there are a lot of people here who are very religious—and not just people who will admit they’re Christian or Muslim or Jewish or Buddhist or whatever, but people to whom it’s very important but who don’t talk about it much. So you just have to find a way to reach out to those people and you’ll find a pretty cool community that you didn’t know was there.

“I’ve never found that my religion clashes with my work here. A lot of what I do in my major is investigating the early forms of Abrahamic texts, looking at the Socratic traditions and the pagan traditions and their influence or lack thereof on the blossoming of Abrahamic traditions throughout the Mediterranean. So a lot of the texts I get to read are foundational Christian texts, foundational Hebrew texts, foundational Islamic texts. And I get a really good sense of how that all plays together. Are there questions that arise, or inconsistencies that I notice and look into? Absolutely. But as Reverend Tharpe, who used to be the Protestant chaplain here, always says, ‘Any true Christian is agnostic three days a week.’ If you’re not questioning, you’re not learning and growing.”

Molly Keller ’19

“I was raised Catholic, baptized, had my first communion, and went to an Episcopalian school from age 3 through fifth grade. Then I transferred to a very liberal private school where my friends were mostly Jewish. But even when I was going to church and Sunday school and at Episcopalian school and being taught religious knowledge, I never felt that invested in it. I remember in fourth grade we had to draw a picture of God, and I was very stubborn, so my compromise with the teacher was drawing a church with little squiggly lines around the steeple to represent a spirit. That was at age 9.

“I didn’t really think about religion very much in high school. It just wasn’t very relevant to my life. But interestingly enough, since coming to college, unexpectedly, I’ve been exposed to a lot of things that have forced me to reconsider. I definitely am not a devout Christian now or anything like that, but for example, my ID1 class was Cult and Culture with Professor Jordan Kirk, and a lot of the questions we focused on were around the manifestation of a God. And I think one of the things that really changed things for me was—we were reading Stories from Jonestown, and there was a passage about how, for some people, God can just be a warm meal and a job or a roof over their heads.

“And so, shifting from God as this man up in the sky to thinking of it as a word that fills in for certain significances—that kind of changed things for me. And then, I’ve been in Religious Ethics class with Professor Oona Eisenstadt, so being exposed to that, and the way different people have their own Tao in their lives, has changed my thinking.

“Religious Ethics, as she presents it to us, is a class that deals with how to live a good life and how different religions and different thinkers grapple with that question. So actually, a lot of the philosophies that came out of that class—whether they be from religious texts or not—kind of helped me think about how I live my life and how I interact with others. I really liked the Bhagavad-Gita but I also really liked Emmanuel Levinas and the way he talked about our intrinsic obligation to the “Other.” And I think that you see that in religion, but it doesn’t necessarily have to go hand in hand. So there are bits and pieces of philosophy that I use to guide my moral and ethical life.

“Again, I’m not a devout anything, and I don’t know if I believe in a God or many gods, but I’m a little more open to the notion that there may be something out there worth believing in. I just haven’t totally figured out what. But I’m not necessarily looking for anything. When religion was a big part of my life, I just sort of took it as it was. Since it hasn’t been a part of my life, I haven’t felt that anything was missing. But I’m open to things that come my way.”

Vian Zada ’16

“I go up on the roof of Pomona Hall often. Being in this quiet place—surrounded by birds and looking up at the clouds—reminds me of creation. It’s a really nice way to clear my mind and remind myself of what matters to me. That’s what praying does for me. It’s really therapeutic because it dissolves whatever stresses I’m going through. It feels purifying. This may sound cheesy, but part of my faith is just looking at all the marvels around me. My love for life and science and how I see that every day just reinforces my wonder for a greater being.

“I grew up with strict but caring parents who tried to maintain the balance between their culture and sending their kids to American schools. I had a lot of rules at home. So being separated from my parents, it’s been interesting to see how, in my lifestyle, I go about following the tenets of my religion without my parents watching me. No one tells me to pray. My parents are never there when I’m at a party and abstain from drinking. Those are things I do for myself.

“I’m not able to pray five times a day, but I do think about God every day. I do fast, for a lot of other reasons besides the reasons that are given to me. I trust my own judgment, and I make my own decisions. It’s not like I look to the Quran as the only source of how to live my life. I’m in a religious studies class right now called Nourishing Life, and we look at a lot of ancient Chinese texts and a lot of Buddhist and Taoist primary sources, and I find myself agreeing with a lot of what I read. I just believe in taking what appeals to you from different religions and different ideas.

“In Islam there’s a lot of emphasis on being compassionate and respectful toward all others—toward life itself. I think I developed my sense of compassion going to Arabic school every Saturday and learning from my mom—just the Golden Rule, basically. I think all religions are beautiful. Religion in itself is, I think, a wonderful tool for helping one shape one’s moral compass.

“My religion also encourages education. Educating yourself is a duty that you’re supposed to carry throughout your whole life. It’s nice to know that I’m supposed to be here.”

—Photos by Carrie Rosema

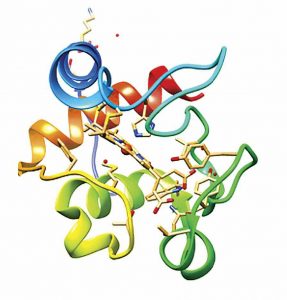

Jennifer Doudna ’85 is a professor of molecular and cell biology and chemistry at the University of California, Berkeley, where she holds the Li Ka Shing Chancellor’s Chair in Biomedical and Health Sciences and is a Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator. As a co-inventor of CRISPR-Cas9, a process that revolutionized gene editing, she has received numerous honors, including the 2014 Breakthrough Prize and both the Gairdner Award and election to the Royal Society in 2016. A chemistry major, she earned her Ph.D. from Harvard University.

Jennifer Doudna ’85 is a professor of molecular and cell biology and chemistry at the University of California, Berkeley, where she holds the Li Ka Shing Chancellor’s Chair in Biomedical and Health Sciences and is a Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator. As a co-inventor of CRISPR-Cas9, a process that revolutionized gene editing, she has received numerous honors, including the 2014 Breakthrough Prize and both the Gairdner Award and election to the Royal Society in 2016. A chemistry major, she earned her Ph.D. from Harvard University. Kiki Ramos Gindler ’83 earned her juris doctor degree from Harvard Law School and specialized in corporate and entertainment law. Today she devotes time to writing, civic affairs and support for the arts. The first Latina president of the Board of Directors for Center Theatre Group in Los Angeles, she serves on the boards of the Los Angeles Opera and the Music Center and is a member of the Blue Ribbon and the National Council for the American Theatre. A philosophy major, she has chaired Pomona reunion committees and hosted several alumni events.

Kiki Ramos Gindler ’83 earned her juris doctor degree from Harvard Law School and specialized in corporate and entertainment law. Today she devotes time to writing, civic affairs and support for the arts. The first Latina president of the Board of Directors for Center Theatre Group in Los Angeles, she serves on the boards of the Los Angeles Opera and the Music Center and is a member of the Blue Ribbon and the National Council for the American Theatre. A philosophy major, she has chaired Pomona reunion committees and hosted several alumni events. Osman Kibar ’92 is founder/CEO of Samumed, LLC, a firm developing drugs for degenerative diseases, regenerative medicine and oncology. Featured on the cover of Forbes Magazine’s “Global Game Changers” issue, Kibar is an entrepreneur and inventor, has founded or co-founded numerous successful companies, and has authored or coauthored many publications and patents. An economics major, he pursued a 3-2 program that also earned him a B.S. in electrical engineering from Caltech. His M.S and Ph.D. in optoelectronics and biophotonics are from UC San Diego.

Osman Kibar ’92 is founder/CEO of Samumed, LLC, a firm developing drugs for degenerative diseases, regenerative medicine and oncology. Featured on the cover of Forbes Magazine’s “Global Game Changers” issue, Kibar is an entrepreneur and inventor, has founded or co-founded numerous successful companies, and has authored or coauthored many publications and patents. An economics major, he pursued a 3-2 program that also earned him a B.S. in electrical engineering from Caltech. His M.S and Ph.D. in optoelectronics and biophotonics are from UC San Diego. Jeff Parks ’02 is a founding partner of Riverwood Capital Management, a globally focused private equity firm that invests in high-growth businesses in the technology and services industries, across a variety of geographic regions and company organizations. He serves on the board of directors of several prominent technology companies, including Nutanix, Spredfast and LogRhythm. A double major in mathematics and economics at Pomona, he completed his studies in three years, so he identifies with both the Class of 2002 and the Class of 2003.

Jeff Parks ’02 is a founding partner of Riverwood Capital Management, a globally focused private equity firm that invests in high-growth businesses in the technology and services industries, across a variety of geographic regions and company organizations. He serves on the board of directors of several prominent technology companies, including Nutanix, Spredfast and LogRhythm. A double major in mathematics and economics at Pomona, he completed his studies in three years, so he identifies with both the Class of 2002 and the Class of 2003. Since joining Google in 2007, Christina Wire ’87 has led a variety of groups across sales, marketing, operations, and corporate philanthropy. Today, she is the director of sales and business operations for Google Fiber. She has also held leadership roles at Intel, Stanford University, and the U.S. Department of State, where she began her career. She holds master’s degrees from Columbia University and Northwestern’s Kellogg Graduate School of Management. As National Chair of the Annual Fund, she was an ex-officio member of the Board from 2014 to 2016.

Since joining Google in 2007, Christina Wire ’87 has led a variety of groups across sales, marketing, operations, and corporate philanthropy. Today, she is the director of sales and business operations for Google Fiber. She has also held leadership roles at Intel, Stanford University, and the U.S. Department of State, where she began her career. She holds master’s degrees from Columbia University and Northwestern’s Kellogg Graduate School of Management. As National Chair of the Annual Fund, she was an ex-officio member of the Board from 2014 to 2016. BIOLOGY: Assistant Professor of Biology Wallace Meyer

BIOLOGY: Assistant Professor of Biology Wallace Meyer CHEMISTRY: Professor Roberto Garza-López

CHEMISTRY: Professor Roberto Garza-López Each spring, juniors and seniors recognize outstanding Pomona professors by selecting the recipients of the Wig Distinguished Professor Award, the highest honor bestowed on faculty. This year’s recipients are (left to right in the image above):

Each spring, juniors and seniors recognize outstanding Pomona professors by selecting the recipients of the Wig Distinguished Professor Award, the highest honor bestowed on faculty. This year’s recipients are (left to right in the image above):

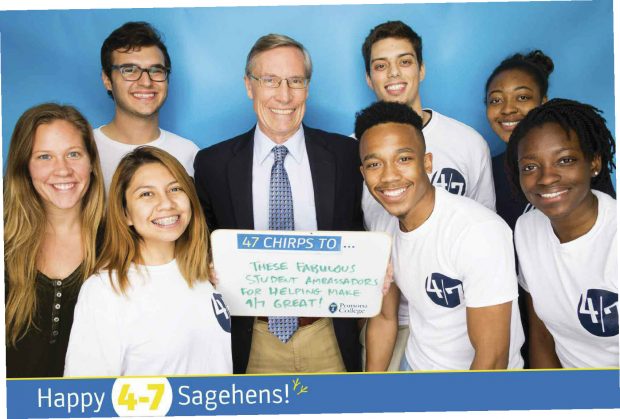

47 hearty chirps to Onetta Brooks ’74 for a year of thoughtful leadership and dedicated service as Pomona’s 2015–16 President of the Alumni Association! Onetta proved a wonderful steward for the board’s evolution to a more action-oriented group, and exhibited her commitment to a thriving alumni community throughout the year during alumni events and 4/7 activities, organization of responses to the Title IX policy and engagement in conversations about

47 hearty chirps to Onetta Brooks ’74 for a year of thoughtful leadership and dedicated service as Pomona’s 2015–16 President of the Alumni Association! Onetta proved a wonderful steward for the board’s evolution to a more action-oriented group, and exhibited her commitment to a thriving alumni community throughout the year during alumni events and 4/7 activities, organization of responses to the Title IX policy and engagement in conversations about May 29–June 10, 2017

May 29–June 10, 2017

“It was incredibly difficult for me to take on a class that removed the sanctity of spirituality from the text.” says Abram. “Initially it felt really disrespectful to me. I didn’t feel like we were giving the due deference and respect.”

“It was incredibly difficult for me to take on a class that removed the sanctity of spirituality from the text.” says Abram. “Initially it felt really disrespectful to me. I didn’t feel like we were giving the due deference and respect.”

“It was a good environment for people to do the wrong thing,” she says.

“It was a good environment for people to do the wrong thing,” she says.