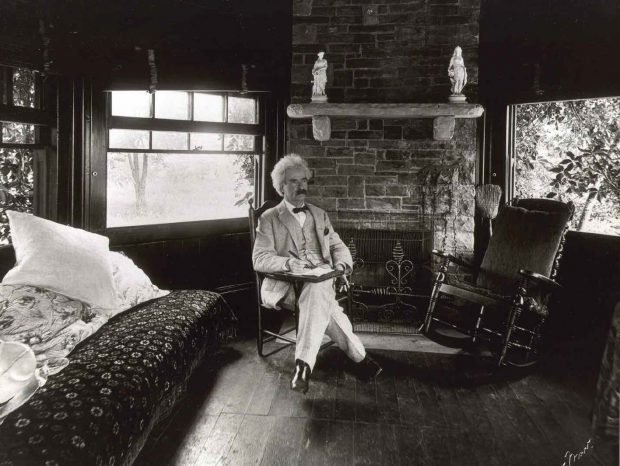

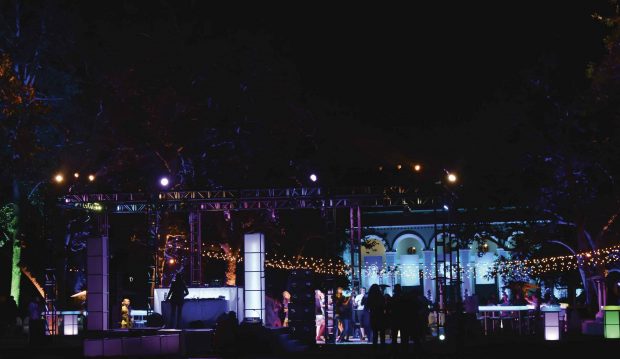

Douglas Preston ’78 in the unnamed river deep in the Honduran jungle

DOUGLAS PRESTON ’78 SAYS he keeps bank hours, writing from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. No dead-of-the-night or predawn creative marathons. The buttoned-down approach might be surprising given the risks he will take to get a good story. In 2015, Preston joined an expedition to see firsthand whether a 500-year-old legend was true. Was there a lost city of immense wealth hidden deep in the Honduran jungle? Indigenous tribes had spoken of this sacred city since the days of conquistador Hernán Cortés. In The Lost City of the Monkey God, Preston narrates an adventure you couldn’t dream up (well, maybe in a nightmare). He and his fellow adventurers found an impenetrable rain forest, deadly snakes, a flesh-eating disease—and the remains of an ancient city rich with artifacts.

Pomona College Magazine’s Sneha Abraham talked to Preston about his search for a vanished civilization. This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

PCM: What inspired you to go on this adventure?

Preston: I’ve been following this story for a long time. Honestly, I’ve never quite grown up. I’ve always thought that it would be exciting to find a lost city. When I was a kid I was always interested in reading about the discovery of the Maya cities, the tombs in ancient Egypt, the tomb of King Tut. I just loved those stories. But as I became an adult I realized, “Well, all the lost cities have been found, so that one childhood dream is never going to come true.” But then it did come true. So, I guess that’s why I was so intrigued by the story of this legendary lost city. It’s remarkable to me that in the 21st century, you could still find a lost city somewhere on the surface of the Earth. Amazing.

The head of a fer-de-lance, tied to a tree as a reminder of the jungle’s hidden dangers

PCM: What did your family think about your going on this particular adventure, knowing the risks involved?

Preston: Well, I didn’t tell my mother because I didn’t want her to worry, but she found out anyway. But my wife is just as adventurous as I am, and her problem was that she wasn’t going. She wanted to go!

To be honest with you, I didn’t realize just how dangerous this environment was until I was actually in it. Now, I’d been warned. People talked about it and I was fully briefed. But I dismissed those warnings, thinking, “It’s exaggeration. This is for people who’ve never been in a wilderness before.” I assumed they were giving us the worst-case scenario. I didn’t take it all that seriously. Then I entered that jungle environment and realized it was even worse than described.

PCM: Were you afraid when you arrived and you realized just how dangerous it was?

Preston: Oh, I wasn’t at all afraid in the beginning because it was gorgeous. It was amazing to be in a place where the animals had never seen people. They weren’t frightened of us. But where I had the come-to-God moment was when I saw that gigantic fer-de-lance coiled up that first night, highly aroused and in striking position, tracking me as I walked past.

The head of the expedition, a British SAS [Special Air Service] jungle warfare specialist, tried to move the snake but ended up having to kill it because it was so big. The fight was terrifying. That snake was striking everywhere and there was venom flying through the air. It was really shocking. After that, I felt a little shaky. I thought, “Well, this is sort of a dangerous environment, isn’t it?”

PCM: Are there many places in the world that are left unexplored?

Preston: There really aren’t. But even today there are some areas in the mountains of Honduras that remain unexplored. The thickest jungle in the world covers incredibly rugged mountains. When you’ve actually been in that jungle, you realize the steepness of the landscape and the thickness of the jungle make it almost impossible to move forward anywhere, except by traveling in a river or stream. You can’t get over the mountains. You just can’t get over them. You can fight with machetes for 10 hours and be lucky to go two or three miles.

And then, of course, there are all the snakes. The number of poisonous snakes in that area is staggering—and you can’t see them.

PCM: Are you in grasslands? What is the terrain like?

Preston: Well, it’s interesting that you mention that. Most of it is really thick jungle, but where there isn’t jungle, there’s high grass. It’s nine or 10 feet tall and it’s very thick-stemmed. It’s almost like wood. It’s the worst stuff to travel through. You hack away at it with a machete and you can barely make any forward movement. There are snakes hiding in the grass. They climb up into it so there’s always the chance of their falling down on you.

Wherever you are, when you move forward after cutting through with machetes, you’re stepping through leaves and debris that are lying on the ground. It’s two feet deep. You have no idea where you’re putting your feet.

So it’s a really frightening thing when you see just how common the snakes are in there.

PCM: Would you talk about places that are unexplored—like the lost city at the site known as T1? What do you think places like these, for lack of a better phrase, do for the human psyche? Specifically, what did T1 do for you as a group? And broadly speaking, what is it about these unexplored places that is important or significant for us as human beings?

Preston: There are layers of answers to that question. The first is that on a personal level, when you’re there, you realize just how unimportant you are. This is an environment that is not only indifferent but is actively hostile to you. It’s important, I think, for human beings to be humbled by nature once in a while.

On a much deeper level, these environments that haven’t been touched by human presence are extremely rare on the surface of the Earth. It’s vital for us to protect them.

Conservation International sent 14 biologists down into this valley, and they set camera traps. They recently brought those camera traps out, and they saw the most amazing animals—animals thought to be extinct, species that were unknown to science, and unbelievably dense numbers of big cats. There are mountain lions, jaguars, margays, ocelots. Apex predators.

And they’re everywhere in that valley. They’ve never been hunted by people. And what they prey on are animals like peccaries and tapirs, which are also heavily hunted by humans. There are so many peccaries and tapirs in this environment that they support a very large number of these apex predators. This is truly a rain-forest environment that is what it was like before the arrival of human beings and in equilibrium. It’s a beautiful thing to see that.

PCM: Did you feel that others in the expedition group were sharing the same sort of response to that experience?

Preston: Yes, I did. We had 10 Ph.D. scientists with us on this expedition. We had ethnobotanists, three archaeologists, an anthropologist, engineers and others. And all of them were deeply affected and impressed by what we saw. They had the scientific background to appreciate it on a deep level. While I was appreciating it on more of a layman’s level, they understood it on a scientific level, and it was extremely impressive to them.

PCM: When you open the book, it begins as an adventure story, but it turns into a history lesson and a biology lesson. Obviously, it’s still an adventure book, but there are many layers to it. You talk about the historic decimation of the population in the New World versus the lack of decimation in the Old World. Is what you put forth something that’s accepted by the mainstream? Obviously, the numbers seem to bear that out, but are other people talking about it in these terms?

Preston: Yes, I would say that the view I presented is the consensus view. However, it is controversial.

PCM: Would you talk about that?

Preston: Everyone agrees that there is a tremendous die-off among the indigenous people of the New World from Old World pathogens. The controversy is what percentage of people died. There are those who say, “Well, we don’t have solid evidence that 90 percent to 95 percent died. All these numbers that the early Spanish give us, they’re very unreliable.” But the doubters have not come forward with their own numbers. They just say it’s all very unreliable.

However, with no event in history are we given reliable numbers, especially that far back. It’s really a question of looking at all the evidence, the confluence of evidence, and coming up with the most reasonable interpretation. And the most reasonable interpretation, which is, in fact, the consensus, is that there was a 90 percent mortality rate from European diseases. That’s just staggering.

Of course, the big question is, “How many people were in the New World before the Europeans arrived? What was the population? We have very good numbers on what the populations were after, but we don’t know how many were there before. And, again, I think the consensus view is that the aboriginal populations in the New World were quite high.

PCM: Your group got quite the negative backlash from the archaeological community. How do you feel about that today? And do you still think those objections are primarily turf battles, jealousy, politics? Would you talk a little bit about that?

Preston (right) and Chris Yoder wading in the unnamed river

Preston: In my book I try to balance some of the legitimate objections with some of the ones that were not legitimate. To put it in perspective, it was a very small group of archaeologists objecting very vociferously.

The Honduran archaeologists who dismissed our findings were individuals who had been removed from their positions following the military coup in Honduras in 2009. The military removed the leftist president and then turned the government back over to the civilian sector, and they had new elections. A leftist government was replaced by a rightist government. In the process, several Honduran archaeologists lost their jobs and new archaeologists were brought in. Some of the dismissed archaeologists did not look with approval on our cooperating with the current government. On the American side, there were several archaeologists who specialized in Honduras who were upset that the discovery was made not by archaeologists but by engineers using lidar, which is an extremely expensive technology unaffordable to most archaeologists. They also objected that the expedition was financed not by archaeologists but by filmmakers. But since my book was published, along with several peer-reviewed papers on the discovery, the objections have ceased.

When archaeologists first heard about the discovery, they initially didn’t know anything about it. There were no scientific publications yet. They heard that a “lost city” had been found, and some reacted with understandable skepticism. But then when the scientific publications started appearing, the criticism ceased. As of now, almost a dozen archaeologists have worked at the site, all from top institutions—Harvard, Caltech—as well as archaeologists from Honduras, Mexico and Costa Rica. When the doubters read those scientific publications and saw the lidar images of the city, they realized, “Oh, wow, this really is a big find.”

The fact is the importance of this discovery isn’t just archaeological. It has stimulated the Honduran government into rolling back the illegal deforestation of this area and encouraged it to preserve this incredibly pristine and untouched rain forest for the future. That might be even more important than the archaeological discovery. Preserving that rain forest is crucial.

PCM: Talk a little bit about that preservation, because you write in the book about the encroaching destruction of these rain forests and jungles. Do you feel that the protection is going to be effective?

Preston: Well, it’s hard to say. Deforestation is a huge problem. The land is being cleared, most of it, not for timbering, not for the value of the logs, but for the grazing of cattle, for beef production. Because of this discovery, the Honduran government has finally taken steps to stop the cutting of trees and the burning of the forests in the area. And also they’ve taken measures to prevent illegal rain-forest beef from entering the supply chains. I was able to show that originally when we went into 2015, some of this rain-forest beef was going to a meat packing company that was selling through a long supply chain to McDonald’s, Wendy’s and Burger King.

Now those three American companies weren’t aware, I don’t think, that they were buying rain-forest beef, because they were buying it several wholesalers removed, through intermediaries. I know that when I brought my evidence to the attention of McDonald’s, they freaked out and immediately sent people down to Honduras and tried to make sure that they weren’t buying rain-forest beef. Obviously, it’s a good business decision not to be accused of being behind the destruction of the rain forest.

PCM: How much of the site has been excavatied, and how many of the artifacts have been retrieved?

Preston: The city of T1 itself probably covers 600 to 1,000 acres. That’s a very rough guess. Only 200 square feet have been excavated. In that area, they took out 500 sculptures from a cache at the base of the central pyramid. There is so much more still in the ground. It’s just incredible. But the Hondurans are not going to excavate the city. They understand, everyone understands, that it’s much better to leave it as is. They’re not going to clear the jungle or anything like that. They’re going to leave virtually all the rest of it as is.

PCM: So much of it remains untouched still, but do you feel that the experts are gaining more knowledge about this culture that disappeared?

A sculpture of a “were-jaguar” found at the site of the lost city

Preston: Yes, this culture is so little known and uninvestigated that it doesn’t even have a name. They’re just the ancient people of Mosquitia. But they had a relationship with the Maya. It’s a very interesting question as to what the relationship was. The city of Copán is 200 miles west of the site of T1. After Copán collapsed, a lot of Maya influence flowed into the Mosquitia region. The ancient people of Mosquitia then started building pyramids. They started building ball courts and playing the Mesoamerican ball game. And they started laying out their cities in a kind of vaguely Maya fashion. But they weren’t Maya. They probably did not speak a Mayan language. They probably spoke some variant of Chibchan, which is a language group connected to South America.

There are so many mysteries as to who these people were, where they came from, what their relationship was to the Maya, and what happened to them. Now, the excavation of the cache hinted at what might have happened to these people, what caused the collapse not only of T1 but of all the cities in Mosquitia. But we still don’t know anything about their origin, where they came from, who they were. And we have only a vague idea of how they lived in this seemingly hostile jungle environment, how they thrived in that environment.

PCM: You mentioned global warming in the context of the flesh-eating disease you contracted, leishmaniasis.

Preston: Two thirds of the expedition came down with leishmaniasis. The valley turned out to be a hot zone of disease. When I got leishmaniasis, of course, I became very interested in it because it’s a potentially deadly and incurable disease. You find it’s suddenly a rather intense focus of your interest! Epidemiologists have predicted the spread of leishmaniasis across the United States. There was a paper that looked at best-case and worst-case global warming scenarios for the spread of leishmaniasis into the United States. Even in the most optimistic, best-case scenario, leishmaniasis will spread across the United States and enter Canada by the year 2080.

In the entire 20th century, there were 29 cases recorded in the United States, and those were right on the border with Mexico. Since then, leish has been found across Texas and deep into Oklahoma, almost to the Arkansas border. It’s a disease that we are going to have to deal with in the future. There’s no vaccine. There’s no prophylactic for it, unlike malaria. It’s transmitted by sand flies which feed on any number of mammals, from rats and mice to dogs and cats. Sandflies are about the quarter of the size of mosquitos. You can’t hear them. You can’t feel them biting. They come out at night. The disease is very difficult to treat.

PCM: How your current health? You mentioned in your book that the disease is coming back, but you haven’t told your doctor.

Preston: It unfortunately does seem to be coming back. This is not unusual for the strain of leish that we all got. I finally photographed the lesion that is redeveloping. But I haven’t sent it to my doctor yet. I just don’t have the guts to do it.

PCM: So what price are you willing to pay for a story? If you’d known beforehand what would happen, would you have still gone?

Preston: Yes, I would’ve.

PCM: You would’ve?

Preston: Yeah, I would’ve. Honestly, as a journalist, I’ve put myself into some dangerous situations, and if this is the worst that’s going to happen to me, I’m probably ahead of the game. I’m lucky. I would do it again. Look, leishmaniasis is not the worst thing that can happen to you. A lot of people are dealing with a lot worse, like cancer and things like that. So I’m doing just fine.

PCM: Would you go back?

Preston: Well, I would if they discovered something really cool. This culture apparently buried their dead in caves as opposed to in the ground. In this jungle, ground burials are gone. The soil is so acidic that there would be nothing left in terms of bones or remains. But they do find spectacular necropolises in caves in this region. Archaeologists are now exploring the valley for caves, where they hope to find burials full of extraordinary artifacts. That would be an amazing find. I’d go down for that.

The Lost City of the Monkey God

by Douglas Preston ’78

Grand Central Publishing 2017

366 pages | 35 photos and maps

Hardcover $28.00

Paperback $15.99

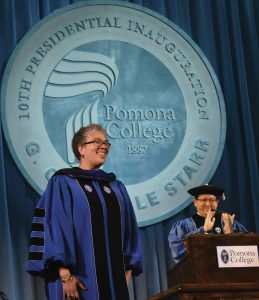

POMONA IS EXTRAORDINARY. We remind ourselves of this proudly when we marvel at the brilliance of our students and faculty, the accomplishments of our alumni, the talent of our staff, the amazing marks Sagehens leave on the world. How many high-achieving people, people who never give up, do we see every day?

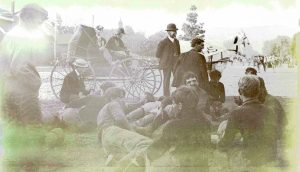

POMONA IS EXTRAORDINARY. We remind ourselves of this proudly when we marvel at the brilliance of our students and faculty, the accomplishments of our alumni, the talent of our staff, the amazing marks Sagehens leave on the world. How many high-achieving people, people who never give up, do we see every day? I was recently visiting my mother (Mayrene Gorton Ogier ’49) in Atascadero, Calif., and noticed the cover photo of the Spring 2017 issue of PCM depicting Pomona’s first Black graduate, Winston Dickson 1904. The magazine was doing secondary duty under a flower pot, but the water-stained photo nevertheless looked familiar. And indeed, it depicts Dickson boxing with my great-uncle, William Wharton 1906.

I was recently visiting my mother (Mayrene Gorton Ogier ’49) in Atascadero, Calif., and noticed the cover photo of the Spring 2017 issue of PCM depicting Pomona’s first Black graduate, Winston Dickson 1904. The magazine was doing secondary duty under a flower pot, but the water-stained photo nevertheless looked familiar. And indeed, it depicts Dickson boxing with my great-uncle, William Wharton 1906. I’ve been meaning to write since reading the touching, inspiring article by Carla Guerrero ’06, “I Do Belong Here,” in the Summer 2017 PCM. Then, this week, President Starr asked us to write our Pomona stories to her, and I responded. It was only right that I also write to you, for it was Carla’s story that inspired me to be in touch with Pomona College again after over 60 years.

I’ve been meaning to write since reading the touching, inspiring article by Carla Guerrero ’06, “I Do Belong Here,” in the Summer 2017 PCM. Then, this week, President Starr asked us to write our Pomona stories to her, and I responded. It was only right that I also write to you, for it was Carla’s story that inspired me to be in touch with Pomona College again after over 60 years. THE NEWEST MEMBER of the Campus Safety team wags his tail lazily as he strolls across campus, pausing to have his back stroked or his ears scratched. But don’t be fooled—Officer Red Dogg is hard at work.

THE NEWEST MEMBER of the Campus Safety team wags his tail lazily as he strolls across campus, pausing to have his back stroked or his ears scratched. But don’t be fooled—Officer Red Dogg is hard at work.