Maintenance Shop Supervisor Orlando Gonzalez is a hands-on kind of guy, working alongside his five-person crew on everything from unclogging shower drains to replacing shingles. But it’s his mind and his memory that are key to keeping the campus in tip-top shape.

Maintenance Shop Supervisor Orlando Gonzalez is a hands-on kind of guy, working alongside his five-person crew on everything from unclogging shower drains to replacing shingles. But it’s his mind and his memory that are key to keeping the campus in tip-top shape.

While work orders come in through an online ticketing system, Gonzalez’ head holds another crucial data center. Growing up with dyslexia, he wasn’t big on writing, so he learned to remember things. “When I stroll the campus,” says Gonzalez, “there’s always flashbacks of what things need to get done, things to go back and check on.”

He knows there’s old furniture stored in such-and-such room, where the plumbing shut-offs are and where not to dig. Everybody, it seems, has his cell phone number, and weekend calls are part of the routine. “I have a lot of information about this campus,” says Gonzalez. “I’ve been in areas where people never go.”

He and his team work from the Gibson Residence Hall’s basement, where the hallway walls of their fix-it lair are lined with the detailed floor plans of campus buildings, all the better for dealing with anywhere from 20 to 40 work orders daily: “We get one done and there’s another just right after.”

Friday afternoon, when other workers might be winding down, is when those get-it-off-the-list work orders flow in fastest. Even summer is no vacation: they bring in extra workers to sweep through every dorm room and make repairs that can’t be done during school. They do, however, get together for a bonding lunchtime barbecue every few weeks.

“Our thing we have here, I think, is special,” says Mike Binney, a generalist on the crew for five years. “We get along, we have an understanding of what each other does—and respect.”

Gonzalez is always looking for a better way. For a time, the College was paying $800 a pop (ouch) to replace damaged security card readers; he worked out a method to only spend $100 to replace just a part.

He has worked at the College since 1997, first as an em- ployee of the central consortium, and then hired by Pomona. The maintenance team includes a plumber, an electrician, a boiler technician and two generalists, but nobody sticks to a single field of work—including Gonzalez. As Binney puts it: “I could be working on a sewer line and if I need help, he’ll jump down there and work with me.”

Still, Gonzalez and crew can’t do it all, not on a campus with 63 buildings, and so he also oversees the work of various contractors, from painters to gutter cleaners. They’d better do it right. If a contractor is getting called in for a repair that’s been done before, he’s going to recall it and go back to check his paper stack of work orders he keeps for the last 10 years. “We need stuff fixed,” Gonzalez says.

Under the night sky, local Native American tribes led an evening of drumming, singing, chanting and ritual dances in early September to mark the beginning of Pomona’s 125th anniversary. Held the same day students gathered in the morning for Convocation, the Native American ceremony brought to campus individuals whose ancestors inhabited this site long before the College was founded.

Under the night sky, local Native American tribes led an evening of drumming, singing, chanting and ritual dances in early September to mark the beginning of Pomona’s 125th anniversary. Held the same day students gathered in the morning for Convocation, the Native American ceremony brought to campus individuals whose ancestors inhabited this site long before the College was founded. Jordan Bryant ’13 grew up playing on the competitive club soccer circuit, taking van rides all over Southern California for weekend tournaments, and shuttling back and forth to practices in Orange County every afternoon. By the time she reached Claremont High School she harbored hopes of playing Division I. It had always been her dream, in fact, to play for USC.

Jordan Bryant ’13 grew up playing on the competitive club soccer circuit, taking van rides all over Southern California for weekend tournaments, and shuttling back and forth to practices in Orange County every afternoon. By the time she reached Claremont High School she harbored hopes of playing Division I. It had always been her dream, in fact, to play for USC. Mahalia Prater-Fahey ’15 knew that she was going to be returning home to San Diego at the end of the spring semester. Thanks to her own timely goal, she got to bring her whole team with her too. Prater-Fahey scored the game-winning goal in triple-overtime as the Sagehens earned the SCIAC championship with a 12-11 win over Redlands, earning a bid to the NCAA Tournament, hosted by San Diego State.

Mahalia Prater-Fahey ’15 knew that she was going to be returning home to San Diego at the end of the spring semester. Thanks to her own timely goal, she got to bring her whole team with her too. Prater-Fahey scored the game-winning goal in triple-overtime as the Sagehens earned the SCIAC championship with a 12-11 win over Redlands, earning a bid to the NCAA Tournament, hosted by San Diego State. Set on enlisting Pomona student musicians to give free lessons to kids, Gabriel Friedman ’12 landed a $10,000 grant from the Donald A. Strauss Public Service Foundation to help pay for cellos, violins and other instruments. But his path to becoming a music mentor began long before that:

Set on enlisting Pomona student musicians to give free lessons to kids, Gabriel Friedman ’12 landed a $10,000 grant from the Donald A. Strauss Public Service Foundation to help pay for cellos, violins and other instruments. But his path to becoming a music mentor began long before that:

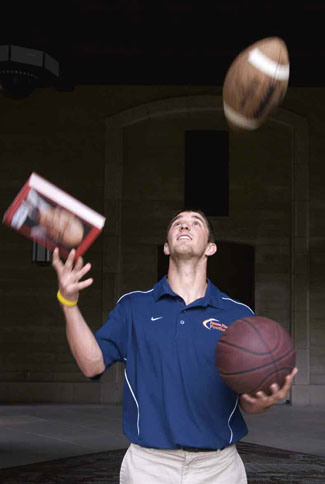

“One of my teammates was supposed to bring my jersey for me, since I couldn’t go on the team bus,” Maki says. “Then I got to Pepperdine, and unfortunately he had forgotten it. So I had to call Jake [Caron PI ’11], and he drove it up to Malibu and finally got it to me just before halftime.” Maki ended up playing six minutes in the second half, as the Sagehens gave the Waves a run for their money before falling 59-50. “I can’t say too many people have ever had a day like that,” says Maki.

“One of my teammates was supposed to bring my jersey for me, since I couldn’t go on the team bus,” Maki says. “Then I got to Pepperdine, and unfortunately he had forgotten it. So I had to call Jake [Caron PI ’11], and he drove it up to Malibu and finally got it to me just before halftime.” Maki ended up playing six minutes in the second half, as the Sagehens gave the Waves a run for their money before falling 59-50. “I can’t say too many people have ever had a day like that,” says Maki.