If you graduated from Pomona College, you understand the meaning of the liberal arts. But to most people across the country and around the world, the concept is murky.

Many imagine that a liberal arts college is focused on the arts and humanities. Yet 39% of Pomona’s Class of 2023 graduates earned degrees in the natural sciences, a division that includes mathematics. Nor should we forget that Pomona’s Nobel Prize winner, gene-editing pioneer Jennifer Doudna ’85, got her start in a chemistry lab on this small liberal arts campus.

Another 24% of Pomona’s 2023 graduates earned degrees in the social sciences, including economics, politics and psychological science, the undergraduate major of Erika H. James ’91, dean of the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania. Some 21% earned degrees in the arts and humanities, as did U.S. Sen. Brian Schatz ’94, a philosophy major. And 16% of 2023 graduates studied an interdisciplinary major—an emblem of the liberal arts that encourages making connections across different fields, such as the Philosophy, Politics and Economics Major (PPE), the major of Hollywood producer Aditya Sood ’97.

The sheer breadth and multifaceted nature of a liberal arts education makes it tough to define.

Y. Melanie Wu, vice president for academic affairs and dean of the College; professor of computer science

“The happiest moment for me is when my students connect the dots and see how their whole education is related,” says Dean of the College Y. Melanie Wu, a computer science professor. “Many students have told me five years after graduation, suddenly it’s all come together in their minds. The Spanish class, the gender and women’s studies class, the art class, the math class. The education they get at Pomona might seem like just sampling or absorbing, but it becomes connected for them and they utilize the entirety of it in their professional and personal lives.”

The Liberal Arts Defined

The concept of the liberal arts draws from the Roman educational system 2,000 years ago, says Chair of the Faculty Ken Wolf, John Sutton Miner Professor of History and coordinator of the Late Antique-Medieval Studies Program.

“In that context, the liberal arts were the subjects that were considered appropriate for a ‘free man’ (liber, in Latin) to know so that he could be an active citizen,” Wolf says. “These were distinguished from the ‘manual arts’ that a person would learn to build things. Nowadays the distinction has more to do with what some have called ‘pure’ subjects (like history, biology or sociology) as opposed to ‘applied’ ones (like engineering, business or nursing).”

Ken Wolf, chair of the faculty; John Sutton Miner Professor of History and coordinator of the Late Antique-Medieval Studies Program

The original seven liberal arts were divided into the quadrivium—arithmetic, geometry, music and astronomy—and the trivium, identified as grammar, dialectic (similar to logic or critical thinking) and rhetoric. Those subjects have evolved and expanded, and though Pomona offers 48 majors, some that are common at other colleges and universities are not to be found here. Specifically, “professional” majors are not part of the Pomona curriculum. Even our Computer Science Major is focused more on theory.

Pomona’s Multifaceted Education

So what is a liberal arts education as offered at Pomona?

An education that is both broad and deep, with exposure to the arts, humanities, natural sciences and social sciences. Small classes focused on discussion, writing and collaborative learning that foster close relationships with professors who often continue to guide students even after graduation. Plentiful opportunities to conduct research with faculty without any graduate students on campus to crowd out undergraduates. A college where almost all students spend all four years in the residence halls, living and studying together and engaging with each other beyond academics. And not least, the freedom to explore many fields so students can discover what it is they want to do with what the poet Mary Oliver called their “one wild and precious life.”

Associate Professor of Gender and Women’s Studies Aimee Bahng, right of the podium, leads a discussion in her Race, Gender, and the Environment class.

While students often wrangle with choosing a major—and “What’s your major?” remains a time-honored icebreaker at college parties and family gatherings—many academic leaders at Pomona believe that decision is overemphasized. That goes as much for Wu, the academic dean and computer science professor, and Associate Dean Pierangelo De Pace, an economics professor, as for Chair of the Faculty Ken Wolf, John Sutton Miner Professor of History and the coordinator of the Late Antique-Medieval Studies Program.

“When they arrive at Pomona College, we try to tell them and try to show them, especially in the first two years of their journey, that this college is not so much about the major,” De Pace says. “Their life will not depend so much on the kinds of specialization they will acquire in college. We try to show them that a holistic approach to education based on rigorous principles is what we think is the key aspect of an education like this one.”

We try to show them that a holistic approach to education based on rigorous principles is what we think is the key aspect of an education like this one.”

—Associate Dean Pierangelo De Pace

Even for students eyeing such fields as medicine, Wu says, nodding at the cadre of Pomona alumni at Harvard Medical School profiled in a story on page 32 and other student journeys featured on page 42, the varied coursework in the liberal arts adds a richness to their education.

“So even though they may major in biology, chemistry or neuroscience and so on, look at the other classes they have taken,” Wu says. “Not necessarily a minor, but just other classes in the spirit of the liberal arts that contribute to their Pomona education and that will contribute to their career paths. They’re going to be better doctors—and better human beings, not just better doctors.”

What Wolf’s students learn in the Late Antique-Medieval Studies Major might not at first glance seem relevant to contemporary life. But the subject is really only a vehicle for mastering the fundamental skills associated with the humanities in general.

“The particular majors that Pomona students pick are far less important than one might think,” says Wolf, whose own undergraduate journey at Stanford University began in pre-engineering and ended in religious studies. (See his 2015 Convocation speech at pomona.edu/2015-convocation.) “What’s more important is that they learn to create, to write, to express themselves orally, to manage data and to use numbers,” Wolf says. “Courses from all across the curricular spectrum contribute to the development of these skills.”

Students share their research posters at the annual Intensive Summer Experience Symposium.

No small part of the job of a liberal arts college is to take a student’s assumptions about what they think they are interested in and expand them.

“This is why as soon as they arrive, we do not try to assign students to advisors based on intellectual affinity,” De Pace says. “Even if a student comes to me and tells me, ‘I want to major in math,’ probably the student will not get a mathematics professor as their advisor. Because the idea is for them to be exposed as much as they can, especially the first two years, to a broader array of fields, disciplines and subjects. And then, of course, they can make up their mind. We try to provide them with this opportunity of exploring and going a little beyond what they think is a real interest at the beginning.”

Professor of Geology Jade Star Lackey works with a student in his lab.First-year students at Pomona still start the fall semester with the traditional critical inquiry seminar—long known as ID1 for the coded interdisciplinary listing in the catalog—a class that can be a deep examination of almost anything under the sun. Later, they select courses to fulfill what are called overlay requirements—writing intensive, speaking intensive and analyzing difference.

“All those are the hallmarks of our liberal arts education,” Wu says. “Those make them a better thinker.”

What might seem a disparate collection of courses at the time eventually coalesces into a broad liberal education, one that equips students to become not only workers but also people in continuous pursuit of learning and a life with meaning.

Return on Investment

There remains the question of value or return on investment (ROI), especially when the cost of attending college in the U.S. roughly doubled in the first two decades of the 21st century.

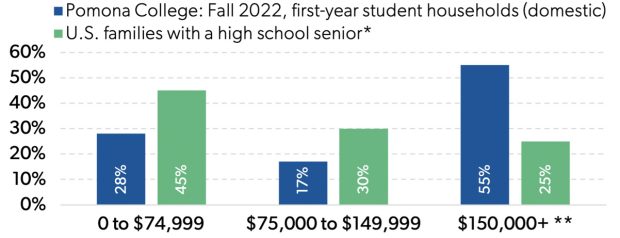

The cost of attending Pomona in 2023-24 was $82,700, including tuition and fees and on-campus room and board but excluding other necessary expenses like books, health insurance and personal spending. (However, more than half of Pomona students receive need-based aid, with an average scholarship or grant amount of $63,044. In addition, Pomona’s new Middle Income Initiative detailed on page 40 seeks to reduce the burden on even more students and their families.)

Yet despite the cost of attending a premier liberal arts college, it often pays off over the long run, according to research published by Georgetown University’s Center on Education and the Workforce in 2020.

What is it about that liberal arts degree that you really value? … that’s exactly what employers want.”

—Hazel Raja, associate dean and senior director of the Career Development Office

In the first decade after enrollment, the full spectrum of colleges and universities—including those with engineering and business degrees as well as two-year colleges that launch graduates into careers earlier—has a higher ROI than liberal arts colleges. But over the course of a career, the median ROI at liberal arts colleges rises to $918,000, more than 25% above the $723,000 ROI of all colleges 40 years after enrollment. And those with degrees from 47 of the most selective liberal arts colleges—a group that includes Pomona—do even better, with a 40-year ROI of $1.13 million.

What explains it? Early high earners might fade as others who earn graduate degrees in business, law and medicine or who move into upper management surpass them. Technology, which often boasts strong starting salaries, can be cyclical and more recent graduates might be in demand because of the rapid evolution of new skills and tools. (As a critically thinking product of a liberal arts college, you already might have surmised that the top ROI among liberal arts colleges belongs to Harvey Mudd, a liberal arts college with an engineering and computer science focus.)

In summary, choosing to study the liberal arts is not turning away from the marketplace.

“Our students are career-driven,” Wu says. “There’s nothing wrong with that—and if our students are not thinking about their profession and their career and what they’re going to become, that’s also a concern.”

Yet too narrow a focus on in-demand jobs of the moment also could put students on the wrong side of a supply-and-demand curve when industry needs shift. There might be no better example right now than the waves of layoffs at big tech companies including Google, Amazon and Meta. Software engineer, one of the coveted first jobs of recent years, is no longer a golden ticket. The exponential growth of Artificial Intelligence, or AI, is one reason.

“Tech is one of the more visible areas within college recruiting but at the same time, a lot of industries are automating,” says Hazel Raja, associate dean and senior director of Pomona’s Career Development Office. “So, when we speak to students who say, ‘I was planning to go into software engineering,’ or ‘I was really leaning toward something in the tech industry,’ we talk to them about ways that they can merge their tech skills into other industries that are also very interesting to them, and perhaps even allow them to elevate their liberal arts education.”

That education, in fact, might be the best to have in the era of AI, with critical thinking and the ability to recognize misinformation and disinformation all the more essential.

“We tell them, ‘You didn’t choose to go to a tech-heavy school. You chose to go to Pomona College, so tell us a little bit about why you chose to pursue a liberal arts degree. What is it about that liberal arts degree that you really value?’” Raja says. “And that’s when they start to pull out the skill sets like, ‘I really wanted to be able to utilize my communication skills,’ ‘I really liked the idea of being in a small environment where I’m learning a lot of different things.’ Well, that’s exactly what employers want.”

Alumni Career Story:

Sophia Sun ’18

Currently working as a senior product manager at Kajabi, Sophia Sun ’18 believes that her experiences as a Linguistics & Cognitive Science Major at Pomona helped her prepare for her current role. She credits her professors and peers for celebrating “being a beginner” and trying new classes. Additionally, she found that Pomona’s rigorous courses and dedicated professors helped her refine her written, verbal and visual communication skills.

Learn more about Sun’s career path.

The 2024 Job Outlook report by the National Association of Colleges and Employers (NACE) bears that out, with employers listing the top three résumé attributes they seek as problem-solving skills, ability to work on a team and written communication skills. Technical skills—which can shift rapidly and vary from company to company—were seventh, behind work ethic, adaptability and verbal communication skills.

The Class of 2024 faces a different hiring outlook than new graduates in 2022 and 2023, who benefited from a post-pandemic hiring boom. In contrast, hiring of new graduates this year was predicted to dip by 1.9% in the NACE report. The leading industry poised to increase hiring was social services.

Now, many of the same students who started their college careers online because of the pandemic shutdown may have to pivot and be nimble again.

“So let’s try to find ways for us to merge your interests,” Raja says. “We spend time asking what they actually are interested in doing. We say, you know, I noticed on your résumé that you got involved in x types of causes or y types of activities. Are there industries out there that perhaps also intrigue you, where you can utilize some of your skill sets, including coding skills and other tech skills, but also some of the other skills that you are developing through your liberal arts education that can culminate into a career path that is more fulfilling for you?”

Many students flock to the same fields in their first jobs, perhaps a result of which companies recruit on campus or offer strong starting salaries. For Pomona graduates in the Class of 2023, the top industry was management consulting followed by higher education and investment banking and management. As always, a significant number of Pomona alumni go directly to graduate school, including 23% of the Class of 2023. (See Pomona’s 2023 First Destinations Report at pomona.edu/outcomes for more.)

“Sometimes it’s the buzzworthy that feels right. We often hear, ‘I want to go into management consulting,’” Raja says, citing a well-paying first job that offers students a chance to do project-based work and even peripherally explore different industries. “I do ask them what management consulting is and if they can’t answer or if they talk about it in a really vague way, we impress upon them doing that research because quite frankly, it’s a great career path for a lot of students but it’s not the only career path. And, it’s a very competitive recruitment process so you have to be committed.”

Sebastian Fish Mathurin ’26 and Katie Stuart ’25 catch up in the Career Development Office.

In some ways, liberal arts colleges remain a hard sell beyond the highly sought-after schools atop the rankings, a group that would include Amherst, Pomona and Williams, to cite a few. Some lesser-known and less selective liberal arts colleges have closed in the face of the continuing decline in students due to demographics, and others are cutting seemingly fundamental majors. Across the country, a number of colleges and universities are turning away from the liberal arts—and in particular the humanities—as a matter of cost-cutting based in part on supply and demand or perceived career value. (See The New York Times’ November 2023 article “Can the Humanities Survive the Budget Cuts?”) Nor are flagship state universities immune. West Virginia University recently cut 28 programs, among them language majors and others in the arts.

The debate about higher education is broad-based, politically charged and ongoing.

What remains is a tension between certification and education, and between what De Pace calls “specialization and diversification,” a push-pull between career preparation and learning to learn in order to understand an ever-changing world and the richness of intellectual life.

To demonstrate the career paths the liberal arts can lead to, the College has undertaken the new Pomona Outcomes Project, which eventually will trace alumni from their majors to their careers and be an interactive tool for future students.

Wu, even with her technology expertise, deeply embraces the liberal arts model but also understands the wrangling about education is far from over in an era when the accumulated knowledge of the world is essentially at everyone’s fingertips.

“It’s a long discussion that we will continue to have for many decades about the value of education, especially the value of a broad education,” she says.

Maryann Zhao ’18

Maryann Zhao ’18 Grant Steele ’18

Grant Steele ’18

Michael Poeschla ’18

Michael Poeschla ’18 Samantha Little ’20

Samantha Little ’20