Julianna Margulies stars as Nancy Jaax in the National Geographic Channel miniseries The Hot Zone, to air beginning May 27.

Richard Preston ’76

JODIE FOSTER WAS SET TO STAR. Robert Redford was on board. Ridley Scott would direct. And then it all fell apart. It was the 1995 blockbuster that never was, and it has bound together two Pomona College alumni for more than 25 years, even though Hollywood producer Lynda Obst ’72 and author Richard Preston ’76 had never met before Obst read the 1992 story in The New Yorker that became the basis of Preston’s nonfiction bestseller The Hot Zone.

Their twisting journey reaches its destination on Memorial Day, when the six-episode limited series The Hot Zone, starring Julianna Margulies, premieres on the National Geographic Channel. A quest that began when Preston was 38 and Obst was 42 is ending in triumph with both old enough to draw Social Security.

Lynda Obst ’72

“The article set the town on fire from the moment it was published,” Obst says of Preston’s New Yorker story, while sitting in the office of her hillside home in the Silver Lake neighborhood of Los Angeles. “Everyone went insane and had to have it. And I was one of those people.”

By early 1993, Obst had won the rights to Preston’s terrifying true tale about the threat of Ebola and other deadly viruses on U.S. soil. But she lost the agonizing war after Foster pulled out over script differences and rival producer Arnold Kopelson raced into filming a blatant knockoff, the 1995 movie Outbreak, despite failing to secure the rights from Preston.

It was a defeat so painful, so public for Obst—who already had Sleepless in Seattle to her credit and later added Contact and Interstellar—that she made its lessons the first chapter of her 1996 memoir about navigating Hollywood, Hello, He Lied.

“The pressure can crush you or turn you into the diamond version of yourself: hard and brilliant,” she wrote about the necessity of moving on. Yet in the midst of the chapter “Next!” about the ephemeral nature of both defeat and success, she slipped in a caveat: “Reinvention remains an option.”

Reinvention it would be: Last September, The Hot Zone began filming in Toronto, followed by a December shoot in South Africa, a stand-in for 1970s Zaire.

MONTHS EARLIER, AS OBST was busy with preproduction, her satisfaction was palpable. “Somebody called me ‘Tenacious L,’ which is my favorite name I’ve ever been called,” she says with a laugh. “So you know, it feels pretty gratifying. Pretty damn gratifying.”

Within arm’s reach in her office was the final version of the contract with Preston from decades ago.

“I keep it on my bulletin board,” she says. “There are many colleagues I still work with who went through the original crisis of ‘Crisis in the Hot Zone’ with me who are still around now as my peers and allies and friends. And they are having a big laugh.”

Preston says he harbored little hope.

“I had given up,” he says by phone from the East Coast, where he lives near Princeton University. “I really thought it was never going to see the light of day. However, I was aware of one thing—it kind of lingered in the back of my mind—which was Lynda Obst’s vow in her autobiography that if it was the last thing she ever did, she was going to make The Hot Zone. I know Lynda well enough to know that was a blood oath.

“I said to Lynda that this could be described as an odyssey, except Odysseus wandered for 20 years,” Preston says. “Lynda wandered for 25 years. She beat Odysseus.”

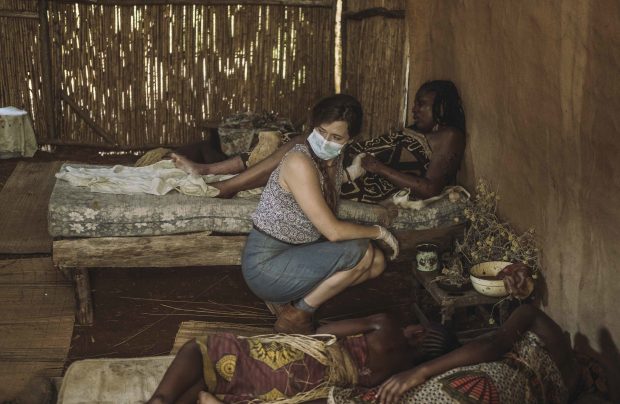

In an episode of The Hot Zone, a character played by Grace Gummer (center) tends to a hut of Ebola victims, including a pregnant woman. —Photo by National Geographic/Casey Crafford

THOUGH THEY CAME WITHIN months of passing each other on Marston Quad—Obst graduated in the spring of 1972, and Preston arrived that fall—the two did not know each other. They also had overlapping circles in New York, where Preston was a contributor to The New Yorker and Obst had been an editor for The New York Times Magazine before moving west, fixing her eye for a story on the film industry and emerging as a powerful Hollywood producer. Obst even knew Preston’s brother, author Douglas Preston ’78, but didn’t make the connection.

Their memories differ as to when they first realized they were two Sagehens trying to make a movie. Obst remembered it as riding in a car to meet Nancy and Jerry Jaax, central figures in the book, but after hearing Preston’s recollection, “I think he’s right and my memory stinks,” she says. As Preston remembers it, Obst mentioned Pomona in their first conversations on the phone.

“My recollection is that she made a real point of that, that she had researched me,” Preston says. “I liked that. Pomona people have a lot of low-key credibility in the world. Pomona people are extremely smart, by and large. So I immediately knew that Lynda was very well educated in the humanities, and that counts for a lot with me, because I have a doctorate in the humanities, in English, but I write about science.

“Those first phone calls, I found myself admiring her, and I really like to work with people I admire,” Preston says. “I admired her because she already had a fantastic track record as a producer. I admired her because she had succeeded as an editor at The New York Times Magazine and then had seemed to shift effortlessly to the West Coast to becoming a producer. And I admired her for her grittiness, for her willingness to get into a major fight with a huge producer like Arnold Kopelson. And I really didn’t like Arnold Kopelson at all.”

Kopelson. the Academy Award–winning producer of Platoon, died last year at 83, but Obst had long studiously avoided mentioning his name, even in her book. Preston says his conversation with Kopelson wasn’t much of a courtship.

“Kopelson had me on the phone, just a typical, unbelievably typical, cigar-smoking Hollywood producer,” Preston says. “And he goes, ‘Richard, you really only have one question you need to ask of yourself. I am going to make this movie, and the only question you need to answer is whether you want to play with me or not.’”

Kopelson later told The New York Times he made no threats but simply stated his intentions: The result was Outbreak, a movie about a fictional deadly monkey virus called Motaba, minus most of the science and transplanted from labs in suburban Washington, D.C., to small-town California, with a military bomber ordered to obliterate the town of dead and dying before the carrier monkey is found and a cure is created from its blood.

THE OFFERS FROM KOPELSON AND OBST, bidding for what was then 20th Century Fox, had been about the same—$100,000 up front and $400,000 if the movie was made. But when Obst and Preston got on the phone, the two Pomona graduates with backgrounds in nonfiction journalism and a passion for science quickly connected.

Obst studied the philosophy of science at Pomona and during a stint in graduate school at Columbia University, and her goal with The Hot Zone as well as in projects involving the late Carl Sagan and Nobel Prize–winning physicist Kip Thorne, both friends, has always been to get the science right. The truth is sometimes scarier than any fiction.

In an episode of The Hot Zone, Dr. Nancy Jaax, played by Julianna Margulies, works with a pipette in the pathology lab. —Photo by National Geographic/Amanda Matlovich

“A lot of other producers talk hype. I talk story,” says Obst, who zeroed in on the central figure of Nancy Jaax in her proposal to Preston. “To me, the vital, amazing thing wasn’t the blood and gore in the piece that attracted some producers. It was that there was a woman Army colonel at the core of this who was a heroine, who exposed herself to danger unwittingly by making a salad for her family, oh my God, on the way to work, where she worked in a [Biosafety] Level 4 containment zone on a regular basis, between visiting her kids at gym and soccer. She was my kind of girl. So I saw a movie star. I saw a great part for women. And I’ve pretty much devoted my career to great parts for women, without sort of consciously being aware of it.”

Kopelson never had a chance.

“I didn’t like the way he had treated me or handled me,” Preston says. “And I found Lynda to be like—this is an odd thing to say, but I felt like she was a kind of samurai, and that she was an expert in martial arts with regard to film production, and that it was just very, very good to have someone like that behind the project.

“I felt like we were two Pomona people going into battle together. And I loved the idea it was a woman warrior. I just loved that.”

But The Hot Zone, the movie, was not to be.

Foster and Redford are both directors as well as actors, and both had strong ideas about the script. Preston thought the original script needed only a little work, and he favored the sensibilities of Foster, who has a degree in literature from Yale. He says Redford wanted to enhance his role by adding an affair with Foster’s married character, Nancy Jaax, and ordered his own rewrite. Foster pulled out of the project over script issues first, and after Meryl Streep considered it before signing on to The Bridges of Madison County, Redford pulled out too. Cameras were rolling for Outbreak. There would be no room in theatres for two monkey virus thrillers at the same time. It was over.

Preston saw Outbreak and calls it “a ridiculous, idiotic film, through no fault of the actors.” (The cast included Dustin Hoffman, Rene Russo, Morgan Freeman, Donald Sutherland, Kevin Spacey and Cuba Gooding Jr.)

Preston says Hoffman called Peter Jahrling, the scientist who discovered the Ebola-Reston virus, in the middle of the night while the film was shooting. “This is a true story,” Preston says. “It goes like this, ‘Ah, is this Dr. Peter Jahrling? Ah, this is Dustin Hoffman. Listen, I’m sorry to bother you, Dr. Jahrling. I’ve got Rene Russo, she’s dying of Ebola, very attractive lady I will say, and we need to cure her in five minutes of screen running time. What do I do, Dr. Jahrling?’”

Jahrling explained a possible cure, Preston says, and at the end of Outbreak, Russo is given an IV bag “of something that looks like Tang breakfast drink, and it cures her in five minutes,” Preston says. “So Jahrling says, ‘I gave them their ending, and they never paid me a dime.’”

Obst, however, refused to watch Outbreak.

“It made me too angry,” she says.

The Hot Zone had come to a painful end, or so it seemed.

“People involved in the project were calling me up and basically weeping over the telephone,” Preston says. But in the end, he adds, “the screenplay was so wretched that it was a relief just to see it put out of its misery.”

BY 2014, THE LANDSCAPE HAD CHANGED. Ebola emerged again in West Africa in an epidemic that ultimately killed more than 11,000 from 2013 to 2016, and health officials are currently battling a new outbreak in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

What’s more, Ebola arrived in U.S. hospitals in 2014, borne by international flights. Two men who traveled from West Africa after contracting the virus, one of them a doctor, died of Ebola. Two nurses treating a dying patient in Dallas also contracted the virus but survived, as did seven other patients treated in the U.S. The Ebola threat was no longer far away in Africa.

Liam Cunningham as Wade Carter and Julianna Margulies as Dr. Nancy Jaax during production of The Hot Zone in Toronto —Photo by National Geographic/Amanda Matlovich

But something else had changed, Obst says: Television entered a golden age. Even Jerry and Nancy Jaax, central figures in Preston’s book, were amazed when the production came together after all this time. “They’d given up on it,” Obst says. “They all think I’m a miracle worker. But the truth is that I’m not a miracle worker: Media has changed. Television grew up, became great, and we were able to take advantage of that.”

Though she says the outbreaks are only a coincidence, they make the series resonate.

“Unfortunately, Ebola did not go away, but Ebola showed its ugliest head in Sierra Leone, became the outbreak that was warned about in Richard Preston’s book, and then simultaneously, this venue developed called ‘Nat Geo,’ in which you could do these things called limited series, which we used to call miniseries, but they were shorter,” she says. “These are at least double the length. And in this venue, you can do the real science.”

Because Fox—now part of Disney after the Hollywood megadeal—owned the intellectual property as well as the National Geographic Channel, Obst saw a way to do the series under the Fox umbrella, and with Ridley Scott’s television production company, Scott Free. “It got to be a better show than it would have been as a movie,” she says.

Preston agrees. “There’s been a sea change in how television series are made and produced and distributed. It’s the Netflix phenomenon,” he says. “The whole story of The Hot Zone has always lent itself to television far better than to a two-hour feature film. You just can’t get the story into a two-hour feature film and preserve the muscularity and the drama of the story.”

Far from the familiar Hollywood scenario in which writers sign away the rights to their work and watch helplessly as it takes a form they never imagined, Preston became deeply involved in the National Geographic series.

“He’s a very important part of the brain trust,” Obst says.

As a co-executive producer and consultant, Preston not only served as a liaison between the production and the real-life characters;he also was a fact-checker on the science, working closely with showrunners Kelly Souders and Brian Peterson on the scripts.

He went through the episodes line by line with them, “getting down to the nitty-gritty of the science,” Preston says. “The end result is that the audience is going to see something that really feels authentic. It’s like you go onto a car lot, you want to buy a car, and you slam the door and nothing rattles.”

Preston also made suggestions to make the series more realistic or dramatic. In one scene where Jaax puts on a protective biohazard space suit as she and a soldier prepare to go into Biosafety Level 4—the extraordinarily dangerous containment area for lethal viruses for which there is no vaccine and no cure—Preston flashed back to his own experience.

“I’m not going to tell you what it is, but it’s what they did to me the first time I went in with a space suit on,” he says. “I told Kelly and Brian about that. I said, ‘This is what Nancy Jaax is going to do to this soldier,’ and they go, ‘Oh my God, yes.’”

With the Hot Zone television series likely to boost sales of the original book, Preston went to work on a revised edition, with scientific updates reflecting what is now understood about Ebola and related viruses that wasn’t available when he wrote the book, including exactly what killed the Danish boy known by the pseudonym of Peter Cardinal, who became ill after entering Kenya’s Kitum Cave.

Slight additional revisions refine the gruesome descriptions of victims’ bleed-outs, a part of the book Stephen King called “one of the most horrifying things I’ve ever read in my whole life.”

And although Preston has written other books in the interim, his next book, Crisis in the Red Zone, is a successor to The Hot Zone and will be published by Random House in July.

“I don’t want to give away too much, but it’s about emerging viruses—viruses coming out of natural ecosystems and invading the human species,” he says.

The original Hot Zone will come to life not on the silver screen but on the small screen, opening May 27 with a three-night run. Like the lethal virus itself, the project retreated and re-emerged, perhaps a stronger version of itself.

The final words of Preston’s book The Hot Zone now seem doubly prophetic:

“It will be back.”

NINETY-SEVEN PERCENT of America’s food-borne outbreaks are confined to a single source in a single state. Wise says these kinds of outbreaks can be caused by anything from chicken at a church supper left uncovered for too long to a fast-food restaurant kitchen forgetting to wash lettuce. When a food outbreak occurs, he said, local and state health inspectors are usually the ones handling the response.

NINETY-SEVEN PERCENT of America’s food-borne outbreaks are confined to a single source in a single state. Wise says these kinds of outbreaks can be caused by anything from chicken at a church supper left uncovered for too long to a fast-food restaurant kitchen forgetting to wash lettuce. When a food outbreak occurs, he said, local and state health inspectors are usually the ones handling the response. “We never figured it out,” Wise said.

“We never figured it out,” Wise said.

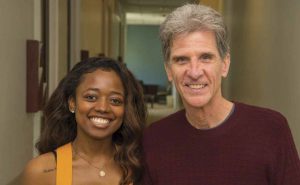

From left: Eric Garcia ’19 and Professor Chuck Taylor

From left: Eric Garcia ’19 and Professor Chuck Taylor From Left: Cynthia Nyongesa ’19 and Professor Richard Lewis

From Left: Cynthia Nyongesa ’19 and Professor Richard Lewis From left: Professor Alexandra Papoutsaki and Caroline Chou (CMC ’19)

From left: Professor Alexandra Papoutsaki and Caroline Chou (CMC ’19)

WANTED Lead Camera and Lights for a documentary-style film.”

WANTED Lead Camera and Lights for a documentary-style film.”

A storyteller from childhood and now an all-grown-up author, Ali Standish ’10 is writing children’s and middle-grade books that are being noticed by children and critics alike.

A storyteller from childhood and now an all-grown-up author, Ali Standish ’10 is writing children’s and middle-grade books that are being noticed by children and critics alike. Pomona College Magazine’s Sneha Abraham talked to Standish about inspiration, imagination, what’s an absolute must in children’s literature and more.

Pomona College Magazine’s Sneha Abraham talked to Standish about inspiration, imagination, what’s an absolute must in children’s literature and more. I’ve just been doing it for really as long as I can remember. Then one of my really good friends, an important person in my life, passed away in fall of my senior year. And a big part of coping with that for me was writing my first children’s lit manuscript. I wrote a manuscript that was a very boilerplate, poorly written fantasy novel. And I was able to submit that as my final project for Children’s Literature 101. So senior year was when I really edged over into writing children’s literature.

I’ve just been doing it for really as long as I can remember. Then one of my really good friends, an important person in my life, passed away in fall of my senior year. And a big part of coping with that for me was writing my first children’s lit manuscript. I wrote a manuscript that was a very boilerplate, poorly written fantasy novel. And I was able to submit that as my final project for Children’s Literature 101. So senior year was when I really edged over into writing children’s literature.

While Avis Hinkson was growing up in a Barbadian immigrant household in Brooklyn, she imagined a career in health care. Instead, her life’s work has been guiding college students, first as an admission officer, later as a director of advising and now as Pomona College’s dean of students. “I didn’t go to college thinking I would stay in college,” she says with a laugh. She tells students that “as a college student, you want to chart a career path, and I encourage you to do that. But I also encourage you to be open to the right and left turns that sometimes take place, because they can lead you to wonderful career spots that you couldn’t have possibly imagined.”

While Avis Hinkson was growing up in a Barbadian immigrant household in Brooklyn, she imagined a career in health care. Instead, her life’s work has been guiding college students, first as an admission officer, later as a director of advising and now as Pomona College’s dean of students. “I didn’t go to college thinking I would stay in college,” she says with a laugh. She tells students that “as a college student, you want to chart a career path, and I encourage you to do that. But I also encourage you to be open to the right and left turns that sometimes take place, because they can lead you to wonderful career spots that you couldn’t have possibly imagined.” Absorb the lesson while growing up in a culturally rich neighborhood that education is the path to a better life. Watch your mother, a seamstress, graduate from college in her 50s after going to work as a teacher assistant.

Absorb the lesson while growing up in a culturally rich neighborhood that education is the path to a better life. Watch your mother, a seamstress, graduate from college in her 50s after going to work as a teacher assistant. Go along with a high school friend to meet a recruiter from Barnard College. Be impressed that the recruiter is African American, and with the help of financial aid (Barnard costs more than your father makes in a year’s work as a mason), become one of about 25 Black students in a class of 500.

Go along with a high school friend to meet a recruiter from Barnard College. Be impressed that the recruiter is African American, and with the help of financial aid (Barnard costs more than your father makes in a year’s work as a mason), become one of about 25 Black students in a class of 500. Bump into Barnard student Vernā Myers on your way to the career center to pick a work-study job as a first-year student. Heed the advice of the future Netflix vice president when she suggests a job in the admissions office. Create Barnard’s first overnight-visit program for prospective students of color.

Bump into Barnard student Vernā Myers on your way to the career center to pick a work-study job as a first-year student. Heed the advice of the future Netflix vice president when she suggests a job in the admissions office. Create Barnard’s first overnight-visit program for prospective students of color. Listen to Barnard senior Marcia Sells (a future dean of students at Harvard Law School) when she encourages you to run for the student seat on the Board of Trustees. Take part in the decision that Barnard will remain a women’s college instead of merging with Columbia.

Listen to Barnard senior Marcia Sells (a future dean of students at Harvard Law School) when she encourages you to run for the student seat on the Board of Trustees. Take part in the decision that Barnard will remain a women’s college instead of merging with Columbia. After graduation, become an admissions counselor at Bowdoin, establishing minority recruitment programs there. Decide on a career in higher ed instead of health care, later earning an M.A. in student personnel administration from Columbia University’s Teachers College and an Ed.D. from Penn.

After graduation, become an admissions counselor at Bowdoin, establishing minority recruitment programs there. Decide on a career in higher ed instead of health care, later earning an M.A. in student personnel administration from Columbia University’s Teachers College and an Ed.D. from Penn. Establish minority recruitment programs at Cornell before coming to Pomona in 1990 as associate dean of admissions. Contribute to Pomona’s minority recruitment plan before moving on to become director of minority recruitment at the University of Southern California.

Establish minority recruitment programs at Cornell before coming to Pomona in 1990 as associate dean of admissions. Contribute to Pomona’s minority recruitment plan before moving on to become director of minority recruitment at the University of Southern California. As director of advising for more than 18,000 undergraduates in the College of Letters and Sciences of the University of California, Berkeley, get an eye-opening look at the bureaucracy of a large public university. While furloughed amid a California budget crisis, remember the allure of small liberal arts colleges.

As director of advising for more than 18,000 undergraduates in the College of Letters and Sciences of the University of California, Berkeley, get an eye-opening look at the bureaucracy of a large public university. While furloughed amid a California budget crisis, remember the allure of small liberal arts colleges. Go home again and call your 96-year-old father to tell him you’ve been named as Barnard’s first African American dean of the college. Feel grateful that a man who felt most comfortable talking with the public safety officers and janitors when visiting campus lived to see it.

Go home again and call your 96-year-old father to tell him you’ve been named as Barnard’s first African American dean of the college. Feel grateful that a man who felt most comfortable talking with the public safety officers and janitors when visiting campus lived to see it. Go home again (again). Leave behind your newly renovated childhood home in Brooklyn and return to Pomona as you are drawn back to the campus where G. Gabrielle Starr has recently become Pomona’s 10th president, the first woman and first African American to lead the campus.

Go home again (again). Leave behind your newly renovated childhood home in Brooklyn and return to Pomona as you are drawn back to the campus where G. Gabrielle Starr has recently become Pomona’s 10th president, the first woman and first African American to lead the campus. Discover that April Mayes ’94 is now a professor of history at Pomona, and Nate Kirtman III ’92 is on the Board of Trustees. (Both were student workers in admissions when you worked at the College before.) Know that the seeds you planted have helped make Pomona one of the most diverse private residential liberal arts colleges in the country.

Discover that April Mayes ’94 is now a professor of history at Pomona, and Nate Kirtman III ’92 is on the Board of Trustees. (Both were student workers in admissions when you worked at the College before.) Know that the seeds you planted have helped make Pomona one of the most diverse private residential liberal arts colleges in the country.

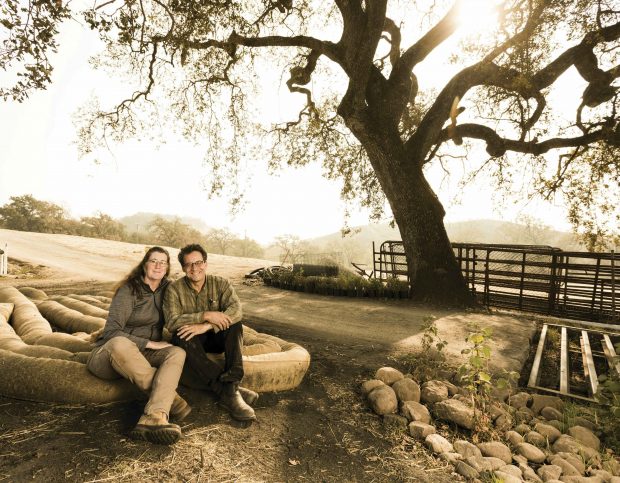

“Jim Kauahikaua, U.S. Geological Survey’s Hawaiian Volcano Observatory. I’ll do a quick summary of what’s happening. Vents eight and 16 have reactivated. Twenty-two and 13 are still the main southbound channels going into the two ocean entries, though those have been quite weak today …”

“Jim Kauahikaua, U.S. Geological Survey’s Hawaiian Volcano Observatory. I’ll do a quick summary of what’s happening. Vents eight and 16 have reactivated. Twenty-two and 13 are still the main southbound channels going into the two ocean entries, though those have been quite weak today …” But the main thing that Kauahikaua says tried his patience during those long weeks was the bureaucratic conceit of some of the early incident management teams sent in by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), which used the emergency as a training exercise. “None of them had Hawai‘i experience or eruption experience, so—for example, safety out in the field. All of a sudden, we had these people from God knows where, Georgia maybe, telling us what was safe and what was not safe. And that rubbed a lot of people the wrong way.”

But the main thing that Kauahikaua says tried his patience during those long weeks was the bureaucratic conceit of some of the early incident management teams sent in by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), which used the emergency as a training exercise. “None of them had Hawai‘i experience or eruption experience, so—for example, safety out in the field. All of a sudden, we had these people from God knows where, Georgia maybe, telling us what was safe and what was not safe. And that rubbed a lot of people the wrong way.”