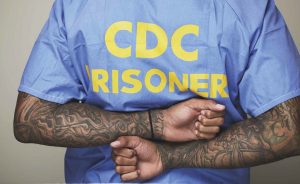

Entrepreneurs in Training (EITs) welcome Glazier and other volunteers at a prison event in Lancaster, Calif.

GAMES AND ICEBREAKERS are often used at business conferences to create some fun and make strangers comfortable with each other. But at a recent meeting of Defy Ventures, which helps people from prisons prepare for life on the outside, one empathy-building exercise quickly turns dead serious. It’s called Step to the Line, and though not a word is spoken, much is revealed.

On a sunny Saturday in mid-January, about a dozen former inmates from two Los Angeles halfway houses gather for the event at a modern downtown office complex. They are met there by a group of volunteers, men and women from the business world recruited to lend their expertise on writing résumés, polishing personal statements and perfecting business plans.

Defy calls the event a Business Coaching Day, and it’s led by Andrew Glazier ’97, the nonprofit’s national president and CEO. It’s part of the organization’s overall prison rehabilitation program called CEO of Your New Life, which aims to build self-confidence as well as skills.

At Defy, the group exercises are meant to be healing. They help participants develop a healthy self-image and positive attitudes. The organizers provide a well-studied set of aphorisms to live by.

Shame is destructive. Learn to forgive, not judge. You are not defined by your mistakes. You deserve a second chance. Foreswear negative labels. You are not criminals, convicts or felons. You are EITs— Entrepreneurs In Training.

Above all, realize that the solution is already inside you. Many of the same skills that brought you success as, say, a drug dealer can be applied to any legal enterprise.

In short, to quote Defy’s main motto: Transform the Hustle.

Glazier listening to an EIT share his personal statement during a coaching day.

GLAZIER HIMSELF COMES from a privileged background that could not be more remote from the life experience of his incarcerated clientele. For the public face of Defy Ventures and its chief fundraiser, that disparity can be a handicap, he concedes. Sometimes he finds himself forced to answer questions of class and race when pitching new potential donors.

“In the funding community now there’s a lot of interest in seeing people who have ‘lived experience’ running organizations and working in the nonprofit space,” he explains. “I think part of it comes from the idea that, look, for a long time it’s been just a bunch of well-meaning white people who come and work in communities of color. So sometimes I find I still battle this credibility stuff: What are you doing here?”

Glazier understands why people perceive a disconnect between his upbringing and his prison work and why they might challenge his street cred, so to speak. But he bristles at being “on the receiving end” of that mistrust. “It can be an uncomfortable spot to be in,” he says. “Look, I can’t change who I am. I do know that it’s critical to have people with lived experience within our organization, informing our work. And we do.”

If you’re looking for personal information on Glazier, you won’t find much on social media. He’s not one to overshare; so he keeps a light digital footprint, mostly on LinkedIn and all about business. But Glazier opened up during a casual lunch recently at the Wasabi Japanese Noodle House, a five-minute walk from his Wilshire Boulevard offices in Koreatown. He talked easily about his evolving life goals, his family, education and the circuitous career path that brought him to the transformative prison work he never dreamed he’d be doing.

Unlike many other Angelenos, Glazier’s roots in the city run deep. His mother descended from immigrants with a long history in Los Angeles. Her maternal relatives arrived from Italy, just in time for his great-grandmother to be “born off the boat from Sicily” in 1908.

Glazier’s father was a doctor who worked for the Veteran’s Administration, where he met his mother, who worked as a secretary for the agency. They married, had three children and settled in Studio City, a well-to-do neighborhood in the eastern San Fernando Valley.

Glazier attended Harvard-Westlake, a college prep he calls “the most elite private school in Los Angeles.” Today, he concedes that his exclusive education had put him in a protective bubble, cloistered from the social ills mushrooming all around him.

But all that changed on April 29, 1992, the day the Los Angeles Riots erupted over the verdict in the Rodney King case.

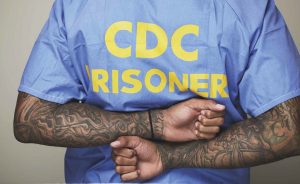

One of Defy’s entrepreneurs in training, referred to as EIPs.

GLAZIER WAS 16. “I had lived my whole childhood in the valley, and I had no idea what was going on eight miles away,” he says. “Then the riots happened. I remember seeing Rodney King getting beaten on TV. Then the city burning. And even in the valley, where it wasn’t nearly as intense, you could still see all the smoke coming over the hill.

“That was really a moment for me of waking up: Oh, my life is not their life. There are things happening that are really close-by that I’m really not aware of. And when I suddenly had greater awareness of my opportunity and privilege, it felt all the more extreme, which in part, I think, drives me to do this work.”

Yet, Glazier never actually planned to work in prison reform. Until recently, if you had told this classically trained cellist with an MBA and a medium build that he would someday wind up working with hard-core prison inmates, he would have scoffed at the notion.

Nothing was further from his mind when he applied to college. He picked Pomona because he wanted a small school, and his parents wanted him to stay close-by.

The Claremont campus also had a strong academic appeal. “I’m a huge fan of the liberal arts,” he says. “It doesn’t matter what you get a degree in, because you’re learning critical thinking and writing. And that’s the education I came out with—a degree in critical thinking and knowing how to write, both important skills that are hard to find.”

Glazier majored in international relations, studied Spanish and Japanese, and spent a semester in Pomona’s program at Tokyo’s International Christian University. At first, he considered joining the foreign service, but that plan never materialized. (Fun fact: his suitemate during junior year was David Holmes ’97, a U.S. State Department employee based in Ukraine who recently testified during the impeachment hearings against President Donald Trump.)

After graduation, Glazier took time to explore. He returned to Japan and taught English for a year. He travelled, settled down and started a family. From 2001 to 2004, he was chief of staff to Marlene Canter, then a newly elected member of the Los Angeles City Board of Education.

“Originally, I wanted to be an elected official,” he recalls, “but five years of working in local and state government sort of cured me of that impulse.”

Nevertheless, the experience continued to stoke a civic calling. The problems he saw in L.A. schools opened his eyes to new realities—kids who are afraid to go to school, who can’t read, who smoke weed in the hallways.

“This is where you really start to see inequities in the system, to see more of the injustices that exist in society,” he says. “I spent my life in private education; now suddenly I have this front-row seat in public schools, and you think, ‘How is this even possible?’”

Glazier then switched gears and joined a small real estate development team, managing an award-winning restoration of historic bungalows in Silverlake. On that job, he recalls, he met and interacted with people with criminal histories for the first time, giving him a glimpse into the challenges they face after prison.

EITs welcoming a volunteer at the start of a Defy coaching day.

Meanwhile, Glazier also went back to school, earning his master’s in business administration from UCLA’s Anderson School of Management in 2006.

Two years later, he decided he’d had enough of real estate, which “didn’t feel meaningful to me.” In October of 2009, he took a job with City Year Los Angeles, a nonprofit that plunged him back into those vexing education problems. The agency works with AmeriCorps volunteers to serve as tutors, mentors, and role models for students in Los Angeles, grades three through 10.

The job gave Glazier his entrée into nonprofit work, where he finally found his mission. He stayed eight years with the education agency, having ascended to second in command in the Los Angeles chapter. When he decided to leave—again with no job lined up—a friend referred him to the opening at Defy, which had recently launched a new Southern California branch.

Glazier has come to see parallels between the problems in public schools and those in public prisons. “They are both large bureaucracies within the state government that are dealing with large numbers of people who are in need of intervention and education,” he explains. “So some of the basic reform ideas that apply to public education apply to prisons too.”

In either system, steering an organization in a new direction can be a herculean task. Glazier was well aware of the enormous challenge when he entered the criminal justice reform world three years ago, full of optimism and ambition. But he had no idea of the organizational landmines that awaited him at Defy Ventures, where a scandal was about to shake the nonprofit to its foundation while abruptly catapulting Glazier to the top job.

DEFY VENTURES WAS FOUNDED in 2010 in New York by a charismatic woman named Catherine Hoke, a UC Berkeley graduate and former Wall Street executive. But in 2018, she was forced to resign in the midst of accusations of sexual harassment, misuse of funds and misleading donors with inflated performance reports.

Glazier said the controversial leader had come to personify the organization. She had a golden touch for fundraising and promotion; she courted powerful people in politics and Silicon Valley and had a knack for drawing high-profile media coverage. When she stepped down, Glazier says, Defy seemed doomed, as donors rapidly retreated.

Hoke has denied the allegations, though she previously admitted having sex with ex-prisoners participating in a similar program she had established in Houston in 2004. After being banned from Texas prisons in 2009, she resurfaced in New York where she later faced the new allegations from former Defy employees. An internal investigation, conducted by an outside law firm, found evidence of personal impropriety, but no proof that program results were embellished, donors misled or funds misused.

Glazier joined Defy in May of 2017, charged with building the new L.A. chapter. But before he had completed his first year on the job, the scandal hit, and he was suddenly promoted to president and CEO as the organization ran out of money.

Glazier recalls how he perceived the promotion: “You’re in charge. Here’s a dumpster fire.”

The newcomer scrambled to keep the sinking agency afloat. He was forced to lay off two thirds of the staff, then proceeded “to engineer a turnaround.” Today, the agency is back on solid footing.

Defy’s top goal, says Glazier, is cutting the rate of recidivism, the all-important measure that tracks the proportion of released offenders who return to prison over time. Nationwide, the rate has remained stubbornly high for decades. According to the most recent study released in 2018 by the federal Bureau of Justice Statistics, more than 83 percent of inmates released in 2005 had been re-arrested at least once within nine years. Most, 68 percent, were re-arrested within the first three years. The study followed a random sample of 67,966 prisoners from 30 states, including California, Colorado and New York, all places where Defy programs operate.

Defy’s top goal, says Glazier, is cutting the rate of recidivism, the all-important measure that tracks the proportion of released offenders who return to prison over time. Nationwide, the rate has remained stubbornly high for decades. According to the most recent study released in 2018 by the federal Bureau of Justice Statistics, more than 83 percent of inmates released in 2005 had been re-arrested at least once within nine years. Most, 68 percent, were re-arrested within the first three years. The study followed a random sample of 67,966 prisoners from 30 states, including California, Colorado and New York, all places where Defy programs operate.

Defy’s strategy is essentially simple: Help men and women inside prisons prepare for a successful re-entry by teaching them business and career skills and personal development. Once they’re released, the agency provides continued support through a structured program to help them get a job or start a business.

While still in prison, participants engage in a seven-month curriculum that culminates in a Shark Tank-style competition, in which they pitch their ideas to a panel of business leaders and investors. After graduation and release, winners can bring their ideas to fruition through Defy’s Business Incubator.

ON ITS WEBSITE, Defy tracks results by the numbers: More than 5,200 prison participants, 4,800 volunteers, a one-year recidivism rate of 7.2 percent, an 84 percent employment rate and 143 businesses incorporated over the past eight years.

Like Defy itself, several of these small enterprises go on to employ former prisoners. Two Defy graduates work for Glazier at the agency’s spare and utilitarian offices, where the décor is corkboards and calendars.

Quan Huynh, the organization’s post-release program manager, joined the Defy program as a participant in 2015 while serving a life sentence for murder. He had been convicted in connection with a car-to-car shootout on the Santa Ana Freeway between his Vietnamese gang and members of a rival gang in the other car. He did time in some of the state’s toughest prisons, including Soledad and Pelican Bay.

“For the first 10 or 12 years, I never thought I was going to go home,” says Quan, whose parents fled the Vietnam War when he was an infant. At his parole hearing, he gambled on telling the truth, admitting he had lied in court and coached witnesses. His honesty paid off.

After his release, Defy helped him start his own cleaning company in Fountain Valley. Today, he is founder and CEO of Jade Janitors, currently with six employees, including five who were formerly incarcerated. He was Glazier’s first hire at Defy in 2017.

Another volunteer offering feedback to an EIT at a California prison.

When asked, Quan thinks before offering a job assessment on his boss. “He’s very strategic and organized,” he says. “He’s all about systems and processes. He does not micromanage me at all. He empowers me. He sets the goal and sets high expectations, and we follow through with it.”

For Quan, that management style says, “I trust you.”

PRIVATELY, GLAZIER CAN “sometimes seem a little socially awkward,” Quan says, but he’s confident in the spotlight as Defy’s workshop leader. “He’s right in his comfort zone right there, actually connecting with the participants.”

During the recent Business Coaching Day, Glazier is clearly comfortable leading the icebreakers. In one, he asks people to introduce themselves by dancing their way from their seats to the front of the large hall.

“Quan, have you got some good dance music ready?”

There is no room to be bashful in this exercise. The participants, both budding entrepreneurs and volunteer counselors, make their way to the front, displaying individuality in their step. They strut, stroll, glide, vamp and slow-walk their way to the front, announcing the nicknames they gave themselves. There is Graceful Grace, Fantastic Frank, Kind Kyra and Bashful Benny. And here come Musical Michele, Ambitious Albert, Incredible Ian and Resilient Raul.

In the role of moderator, Glazier as Awesome Andrew is a cross between a motivational speaker, group therapy leader and game-show host. By the time these icebreakers work their wonder, the room is buzzing with laughter and chatter like a nightclub at midnight.

But when it comes time for Step to the Line, Glazier asks for silence. He instructs the group to form two lines along blue tape laid on the floor a few feet apart. Volunteers stand shoulder-to-shoulder on one side facing the Entrepreneurs in Training on the other. Then they all take two steps back from their respective lines, making the distance greater between them.

Glazier ’97 leading one of Defy’s signature exercises, Step to the Line.

Glazier then reads a series of questions. For each one, participants must step forward to their line if they feel the statement is “true for you.” As the exercise goes along, people on both sides of the divide step forward and back with each question, revealing both differences and commonalities.

Soothing guitar and piano music start playing, relaxing as a spa. Glazier’s words float over the room like spiritual meditations. “We don’t do shame at Defy,” he says, speaking slowly with deliberate pauses. “We’re forward-looking. We do empathy. Now, empathy is not pity. Nobody is asking for anybody to feel sorry for them. Feeling sorry for someone isn’t built on respect. But empathy is built on respect and shared humanity. Empathy says that I see you. I hear you. And I understand.”

The first few questions are for fun.

I like scary movies.

I know who Billie Eilish is.

I was the class clown.

As the statements get more probing, responses reveal social divisions. Only two of the EITs, but half of the volunteers, indicate their parents paid for private schools. Only one former prisoner earned a four-year college degree; most dropped out of high school.

Yet people on both sides share sad experiences, with random movements back and forth from the line of truth.

I struggle with my self-confidence to this day.

My mother or father have been to jail or prison.

My parents split up and their divorce deeply wounded me.

I’ve lost someone I love to violence.

An EIT hugs members of his family during an emotional Defy Ventures graduation exercise.

When the questions turn to crime, the results are both surprising and shocking. Surprising to learn that many of the mostly white mentors have been stopped or questioned by police for no reason, and almost all have been arrested. Shocking to see what the EITs have endured in prison. The majority have spent more than four years behind bars, a few more than 20. The visual of men stepping back or remaining on the line as the number of years are called out makes for a powerful moment. Even more so when Glazier asks about a harsh psychological punishment.

I’ve spent time in solitary confinement. (All but two step foward.)

More than two years. (Two men step back.)

Three years. (Three men remain.)

Five years. (Two left.)

Seven. (One man still on the line.)

Ten years. (Finally, all have stepped back.)

The exercise has succeeded. It has stirred passion and compassion, even from this casual observer. And it has forged strong bonds among this unlikely team of strangers, as indicated by their collective shared movement when Glazier delivers the final statements.

I feel proud of the person I am becoming.

Everybody steps up to the lines, and a couple give high fives across the quickly closing gap.

Okay, last one. If it’s true for you, let me hear it. I love being part of the Defy community.

The session ends with cheers, laughter, spontaneous hugs all around.

AT 28, YOUNG, WHO favors bold colored scarves, long sweaters and a silver hoop in her nose, is, well, young for her profession. She was born in Omaha, Nebraska, and her parents divorced in her early childhood. Growing up with a single, Japanese mother profoundly shaped her— especially in a school district that had been created by conservative white parents who were trying to skirt anti-segregation laws. “It felt like our family was very different,” she says. “I know my mom also really struggled sometimes.”

AT 28, YOUNG, WHO favors bold colored scarves, long sweaters and a silver hoop in her nose, is, well, young for her profession. She was born in Omaha, Nebraska, and her parents divorced in her early childhood. Growing up with a single, Japanese mother profoundly shaped her— especially in a school district that had been created by conservative white parents who were trying to skirt anti-segregation laws. “It felt like our family was very different,” she says. “I know my mom also really struggled sometimes.” THE ROLE OF PUBLIC DEFENDER doesn’t come with much of a runway. Once she graduated from law school, Young clerked for several months at the Contra Costa Public Defenders Office—then began representing a full load of clients on misdemeanor charges soon after she passed the bar in January 2017. “When I got hired, I quite literally had three days’ transition to begin representing 110 clients, some of whom had trials set,” she remembers with a shudder and smile.

THE ROLE OF PUBLIC DEFENDER doesn’t come with much of a runway. Once she graduated from law school, Young clerked for several months at the Contra Costa Public Defenders Office—then began representing a full load of clients on misdemeanor charges soon after she passed the bar in January 2017. “When I got hired, I quite literally had three days’ transition to begin representing 110 clients, some of whom had trials set,” she remembers with a shudder and smile.

Defy’s top goal, says Glazier, is cutting the rate of recidivism, the all-important measure that tracks the proportion of released offenders who return to prison over time. Nationwide, the rate has remained stubbornly high for decades. According to the most recent study released in 2018 by the federal Bureau of Justice Statistics, more than 83 percent of inmates released in 2005 had been re-arrested at least once within nine years. Most, 68 percent, were re-arrested within the first three years. The study followed a random sample of 67,966 prisoners from 30 states, including California, Colorado and New York, all places where Defy programs operate.

Defy’s top goal, says Glazier, is cutting the rate of recidivism, the all-important measure that tracks the proportion of released offenders who return to prison over time. Nationwide, the rate has remained stubbornly high for decades. According to the most recent study released in 2018 by the federal Bureau of Justice Statistics, more than 83 percent of inmates released in 2005 had been re-arrested at least once within nine years. Most, 68 percent, were re-arrested within the first three years. The study followed a random sample of 67,966 prisoners from 30 states, including California, Colorado and New York, all places where Defy programs operate.