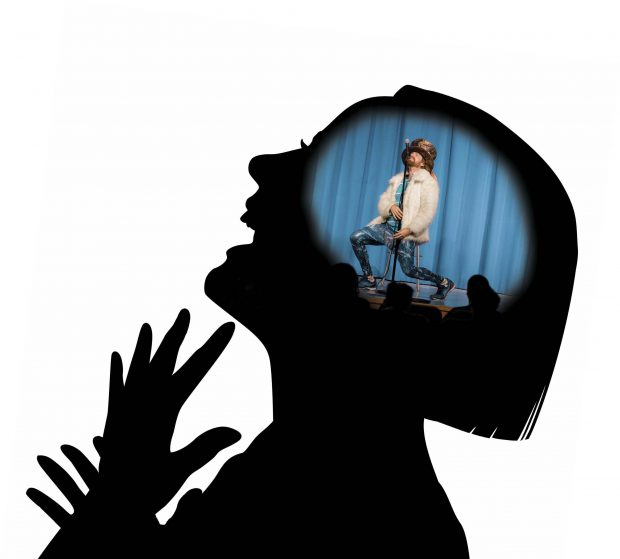

ON A RANDOM weeknight at a comedy club in Burbank, Pomona College Professor Ori Amir bounds onto the stage.

ON A RANDOM weeknight at a comedy club in Burbank, Pomona College Professor Ori Amir bounds onto the stage.

“Hello, party people!”

By day, the bearded redhead with perpetually tousled hair is a visiting professor of psychology who has taught at Pomona since 2017. By night? An amateur stand-up comic.

“As you can tell by my accent, I am a neuroscientist,” the native Israeli says, drawing titters from an audience that doesn’t quite know what to believe. “Sorry, I forgot I’m in Hollywood: I’m a neuroscientist-slash-model,” he says.

“I did get a new haircut. I went to Floyd’s and I told them I work at a college, so could you just give me the haircut of whatever celebrity is most popular among college students these days? So they gave me the Bernie Sanders.”

This time, the laughter is in full.

To Amir, stand-up comedy is like a scientific experiment that provides immediate results. You test the hypothesis that your joke is funny: They either laugh or they don’t. There are variables such as word choice, delivery and audience demographics, but the feedback is instant—sometimes painfully so.

His academic research is a far more sophisticated inquiry. Other researchers have used fMRI analysis, or functional magnetic resonance imaging, to study the brain’s responses to humor. Amir’s work with fMRIs and eye-tracking technology is groundbreaking: He studies the workings of the brain during the actual creation of humor.

Comedy, it turns out, is a nearly perfect subject for exploring the creative process.

“It’s a cognitive process that under the right setting could take 15 seconds, and you can replicate it many times. Anybody can at least try to do it,” Amir says. “It’s hard to ask a novelist to come up with a novel while you’re watching.”

Amir’s research has been featured by Forbes, and the journal Nature reported on his work last fall in an article about how neuroscience is breaking out of the lab, citing his doctoral research at the University of Southern California with Irving Biederman on the neural correlates of humor creativity. The Guardian, Reader’s Digest and the website Live Science also have featured Amir’s work.

Amir’s research has been featured by Forbes, and the journal Nature reported on his work last fall in an article about how neuroscience is breaking out of the lab, citing his doctoral research at the University of Southern California with Irving Biederman on the neural correlates of humor creativity. The Guardian, Reader’s Digest and the website Live Science also have featured Amir’s work.

For his research at USC, Amir recruited professional comedians—including some from the Groundlings, the famed Los Angeles improv troupe that helped spark the careers of Melissa McCarthy and Will Ferrell—along with amateur comedians and a control group of students and faculty. He then showed them examples of the classically quirky cartoons from The New Yorker with the original captions removed and asked the subjects to come up with their own captions—some humorous, some mundane and sometimes no caption at all—as he recorded which areas of the brain were activated.

What Amir found was somewhat unexpected: The regions of the brain lit up by the creation of the funniest jokes by the most experienced comedians weren’t so much in the medial prefrontal cortex, the area of the brain associated with cognitive control, but in the temporal lobes, the regions of the brain connected to more-spontaneous association. The findings fit perfectly, he says, with the classic but decidedly unscientific advice by improv comedy coaches to “get out of your head.”

Amir has expanded his work at Pomona, where he teaches such courses as Psychology of Humor, Data Mining for Psychologists and fMRI Explorations into Cognition. His current work uses eye-tracking technology to examine the relationship between visual attention and the creation of humor.

That study has given undergraduate students who are headed toward entirely different careers an opportunity to contribute to research that Amir expects to publish in a scientific journal next year. Recent cognitive graduates Konrad Utterback ’19, who is beginning his career as a financial analyst, and Justin Lee ’19, who plans to go to law school, will be among the paper’s coauthors. Other collaborators include Alexandra Papoutsaki—a computer science professor at Pomona whose expertise in the emerging uses and potential of eye tracking has been featured in Fortune and Fast Company—and students Sue Hyun Kwon ’18 and Kevin Lee ’20, who wrote computer code for the project.

Konrad Utterback ’19 models the use of the Tobii eye tracker to track eye movements as subjects try to create a punchline for an uncaptioned New Yorker cartoon.

Once again using uncaptioned New Yorker cartoons as prompts, Utterback and Justin Lee conducted experiments using a similar assortment of professional comedians that included comics from the Groundlings and Second City, along with amateur comedians and students.

The eye-tracking device—a low-end model by Tobii that costs about $170 and looks like a narrow black bar attached to the bottom of a standard computer monitor—allowed the researchers to chart the movement of the subjects’ eyes on an X-Y coordinate plane over the 30 seconds they were given to look at each cartoon.

The results were then compared to something called a saliency map of the cartoon image.

The results were then compared to something called a saliency map of the cartoon image.

“It’s this algorithm that basically determines which part of the cartoon is the most visually salient; it defines visual saliency in terms of things like edges and contrast and light—factors which are likely to attract low-level, primitive visual attention,” Utterback explains.

Once again, the results were surprising. The expert comedians focused most closely on the salient or conspicuous features of the cartoon, including faces.

“It’s actually a little counterintuitive because you would think, well, you have all this experience doing comedy and then you end up looking at those features that the low-level algorithm has determined to be the most salient ones,” Amir says. “Our interpretation was that it has to do with them actually using the image to generate the captions, using the input to generate associations to come up with something funny, as opposed to trying to sort of top-down impose their ideas.”

That made sense to Utterback.

“The fact that these were improv comedians in particular is relevant because that’s consistent with how comedians do improv comedy,” he says. “They’re basically trained to listen to what other people are saying first and not ruminate internally too much trying to think of something funny on their own, and sort of just be reactive. It makes perfect sense with these results because they were focusing much more on the actual content of the image to create the joke rather than trying to generate it themselves and forcing it to fit the cartoon, which is what we would expect people with no comedy experience to do.”

Justin Lee’s part of the study built on those results, adding the captions the subjects produced to the original cartoons and then asking three different people to rate the funniness of the cartoons and their captions. “We were able to use the data to determine that this fixation on the salient parts of the image directly correlates with how funny the caption actually ends up being,” Lee says.

The students’ findings support Amir’s earlier results. “We basically proved the same thing that he did using a different modality (eye tracking versus fMRI),” Utterback says. “In a nutshell, both experiments show that people with more comedy experience display a higher level of bottom-up, automatic control and less top-down, intentional influence on the humor creation process.”

Growing up in Israel, Amir watched his father “joke all the time” around the house and even do some comedic appearances on Israeli television.He tried his own hand at stand-up for the first time about seven years ago while still in graduate school at USC, telling a couple of jokes at a campus comedy event. Later, he started showing up around L.A. for open-mic nights. He has appeared at some famous L.A. comedy clubs and can even be seen on TV’s Comedy Central and CMT—“assuming you watch those channels 24-7 on a split screen, without blinking,” Amir writes on his comedy website.

His mainstay is performing at smaller clubs, joints still dotted with appearances by famous or once-famous comics, where he can continue to hone his craft. The life of most comedians, he quickly learned, is not what he saw on TV growing up, somebody telling jokes for an hour in a big arena.

“You don’t know the path,” he says. “The path is—you’re going to end up performing for a long time in front of three apathetic strangers at an open mic, and you’re going to wait two hours to do that and have to buy something from the place. Especially in Los Angeles, it’s an extremely competitive sort of thing. But obviously if it wasn’t so rewarding, people would not be working with so much effort.”

“You don’t know the path,” he says. “The path is—you’re going to end up performing for a long time in front of three apathetic strangers at an open mic, and you’re going to wait two hours to do that and have to buy something from the place. Especially in Los Angeles, it’s an extremely competitive sort of thing. But obviously if it wasn’t so rewarding, people would not be working with so much effort.”

Amir’s influences include George Carlin, the late comedian remembered for his HBO specials and his sharp political and social commentary, as well as British comedians Eddie Izzard and Bill Bailey.

As a foreigner and an academic, Amir has an uncommon perspective for a comic. Audiences don’t always believe he is who he says he is. “I had a couple of times when people said, ‘You’re not really a neuroscientist, and your accent is so fake,’” he says with a laugh. Amir also likes to needle Americans with the insight of an outsider.

“I do like being a foreigner, but sometimes I’m a little concerned that Trump is going to deport me now to Mexico,” he says onstage. “I’m trying to seem more like an American by walking around saying American things, like, ‘Hey, this is America—speak English. Jesus loves you. Sign here.’

“I love the American English,” he goes on. “I love how rich your vocabulary is. You have words like communist, socialist, Marxist, anti-American—and these are only just the synonyms for poor.”

Social and political commentary and the typical off-color comedy club fare can be a little dicey for an academic, particularly one without tenure, Amir knows. He doesn’t invite students to his gigs, but his act was squeaky clean the night PCM visited.

“I do actually have a reporter from my college here,” he told the crowd, “so I can’t say any jokes that could be offensive or construed as prejudiced or sexist or dirty in any way, so … Thank you very much, ladies and gentlemen!”

That one, he says later, would have worked better if he had led with it. His comedy is part improv and partly always being refined. He doesn’t expect to give up his day job any time soon, nor does he plan to quit performing.

“I do want to see how far I can get with it,” he says. “Very few people actually make money doing it—and also, my visa doesn’t allow me to do that for money anyway.”

Ba-dum-bump.

Back in the lab, Amir plans to turn his gaze to the potential for artificial intelligence to produce comedy.

His initial instinct is that comedy is an “AI-complete problem”—one of the few things robots are not soon going to be able to do better than humans. There are types of humor, however, that computers should be able to excel at—such as puns, the proverbial lowest form of humor.

“That’s the first type of humor computers are able to do,” he says.

By the way, Amir—who performs around Los Angeles maybe a couple of times a week—already has had the distinction of being the opening act for a joke-telling robot.

The electronic novice of the stand-up circuit was pretty funny, he admits. However, there was a catch.

“The robot told jokes written by a good comedy writer.”