AMY MOTLAGH ’98: REVOLUTION & REDEMPTION

Amy Motlagh’s life journey has been bookended by revolutions. Born to an Iranian father and American mother, she was 2 years old when her family left Iran for San Diego just months before the overthrow of the Iranian monarchy. Now a professor of English and comparative literature at the American University in Cairo, she has found herself caught in the middle of another series of uprisings in Egypt that have inspired her to see her own people’s struggles in a new light.

“When we left Iran, my family settled in a very white neighborhood in San Diego, but I grew up hearing Farsi and knowing a few words. At that time, there was a lot of bad feeling surrounding Iran; particularly in the wake of the hostage crisis, I tried to distance myself from my Iranian heritage. Although he had lived in the U.S. before, my father was ambivalent about living there permanently, and he would often wonder aloud about the life we would have had if we had stayed. During the Iraq War there was a lot of tension at home. I remember intensely watching news from Iran. It could be your family’s house that was being bombed.

I didn’t start thinking about studying Iran until I took a Pomona class with Zayn Kassam called Women in Islam and did a project on [Iranian novelist] Nahid Rachlin. After graduating I finally returned to Iran with my dad, which changed my perception completely—I witnessed a very different Iran from the one I had seen on TV, and was amazed to find that even under this oppressive regime, there was such a vibrant culture. I loved hearing Persian. It’s a language that values wordplay and takes poetry seriously, and I quickly understood how important it was for me to master it.

Eventually, I enrolled in a Ph.D. program in Near Eastern studies at Princeton University. Although I was studying Persian literature, I also felt called to respond to questions about the Iranian diaspora being raised by books like Azar Nafisi’s Reading Lolita in Tehran. As somebody familiar with the American and Iranian literary traditions, I thought I could offer a critical perspective on how these works fit into a longer history of immigration, assimilation and life-writing in the United States.

It was initially frightening to be in Cairo during the demonstrations in January and February. We would hear gunshots or tanks driving by and be scared for friends who were participating. But once we saw what was happening in Tahrir Square with our own eyes, we could see that the protestors were peaceful and well-organized. Their courage has been inspiring. It’s a bit ironic to be experiencing a revolution when my family tried to leave one, but in certain ways [being in Cairo is] redemptive for me: I always felt like I missed out on something that was a huge part of my generation’s experience in Iran. My cousins grew up in a culture that was being radically remade, where people led double lives at home and in public, and where they had to deal with so many issues I didn’t have to deal with. It seems important to now be part of what’s happening in Egypt, even if it’s from the sidelines.

ALDO RAMIREZ ’00: MIGRANT TO MENTOR

For Aldo Ramirez ’00, school was an escape from a hard life toiling in the orchards and fields as a young boy. So, it is no surprise that after graduating from Pomona, he pursued a career in education. He is now putting his experience to work by helping young, low-income immigrants as principal of a small elementary school in the city of San Bernardino.

For Aldo Ramirez ’00, school was an escape from a hard life toiling in the orchards and fields as a young boy. So, it is no surprise that after graduating from Pomona, he pursued a career in education. He is now putting his experience to work by helping young, low-income immigrants as principal of a small elementary school in the city of San Bernardino.

I was born in L.A. and very shortly after, my family had to move back to Mexico. We lived over there for three or four years. It was a very happy time. My parents and my grandparents were hard workers. They had cattle. They had some crops. So, that is what we did out there. Then my family started moving back to the U.S. as farm workers, moving up through California, Oregon and Washington.

My earliest memories of that time were picking apples and pears and peaches, nectarines and things like that in Washington State. … We would get up really early in the morning, sometimes before the sun was out. It was not fun, I can tell you that. It was very hard, carrying a ladder in the morning. Your hands would freeze. Pulling the cherries from the trees, the stems would wear your fingers down. But during that time my parents always tried to stay positive. They always told us they wanted us to go to college and get a college degree so we wouldn’t have to work out in the fields.

It definitely helped with my endurance. I mean, in school it was pretty easy to put forward a lot of effort. When I was going to school, I didn’t have to work in the fields so I loved school. Most of the teachers that I had were fantastic. They wanted us to do well. But my 8th grade teacher, Mrs. Copeland, she was especially kind. She taught me a lot about writing and literature. And she kept track of me when I was going through high school. And in my senior year, I had a 4.0 grade point average so she came over to the high school and she pulled me out and she gave me literature on Pomona College. And she said ‘I think this is a very good school for you to go to.’ She’s the one who steered me that way and helped me put my application together. She just cared. She wanted me to be successful.

One of my first courses I took at Pomona was Raymond Buriel’s Psychology of the Chicano. And that just resonated with me. It was so interesting to start thinking about the psyche of immigrants, specifically from Mexico. Because education was such a positive experience for me, I did some work as part of a mentor program for students from one of the Pomona Unified School District’s middle schools. And so when I graduated I decided to go into teaching. And it was a perfect fit. I mean it gave me the opportunity to give back. Just like Mrs. Copeland helped me, I found myself in the position of being able to help the families of the students I was teaching. I find as soon as I share my experiences with them and I show them pictures of my family, they relate really quickly. And they do look up to me and a lot of them aspire to do what I have done. The city of San Bernardino has a high concentration of English language learners. About 40 percent of the district is English language learners. About 95 percent of the district gets free or reduced-price lunches so we are working with a very needy population.

JOE NGUYEN ’05: A FUNNY THING HAPPENED …

Joe Nguyen ’05 grew up in the Deep South as the son of immigrant parents whose roots stretch from Germany and Austria to Vietnam. So, perhaps it’s only natural that he decided to become a stand-up comedian. Nguyen holds on to his day job working for the state of California and does standup at night in Los Angeles and San Francisco.

Joe Nguyen ’05 grew up in the Deep South as the son of immigrant parents whose roots stretch from Germany and Austria to Vietnam. So, perhaps it’s only natural that he decided to become a stand-up comedian. Nguyen holds on to his day job working for the state of California and does standup at night in Los Angeles and San Francisco.

“My mom’s parents met and got married after World War II in a Jewish refugee camp in Shanghai. They wanted to move to the United States but, because of quotas, went to the Dominican Republic, where my mom and her sister were born and raised. My dad was an officer in the South Vietnamese army. He and his family narrowly escaped when Saigon fell at the end of the Vietnam War. His brother, who was in the Navy, was able to get them all on a ship to Guam.

My parents met while they were in college in Michigan. They moved to Atlanta when my dad got an engineering job there, and that’s where I grew up. When my family all gets together, it’s a very interesting mix. I think that, apart from the kind of food that I enjoy, there’s an open-mindedness that comes from growing up in a multicultural household.

I never considered myself a funny guy until sometime during college, when I realized I enjoyed cracking jokes and entertaining people. At some point, I started watching and listening to more standup comedy and thought, ‘I’d like to try that; I think I can do it.’

I didn’t have a job lined up after graduation, so I moved north with my girlfriend at the time. I took courses and performed at the San Francisco Comedy College, produced and hosted my own comedy show and, after a few years, started opening for some clubs. I moved to Los Angeles a few months ago and am learning the scene here and lining up shows.

My show used to be mostly about being different. From start to finish, it was ‘Hey, I’m a Vietnamese-Jew.’ I think that’s OK for a five-minute set, but when you do 15 minutes, people want something that is little more relatable. A lot of the newer material is less about my racial background. My style is slower paced, kind of dry and generally, pretty clean, like observational comedy. So far, my parents seem supportive. I don’t know if it’s because they’re my parents or if they really approve of me doing standup comedy. They’ve been to a few shows in San Francisco, and I also did one show in Atlanta.

My dad still encourages me to go to law school, but we’ll see about that. Whatever I end up doing, I don’t think I’ll ever quit standup.

I get a little crazy sometimes and look at reviews of my shows online. I’m happy to say that most have been pretty positive. But there was one about a routine I did for the Kung Pao Kosher Comedy show, which is held every Christmas in a Chinese restaurant in San Francisco. It said, ‘Joe was OK, but his material was too much about being Vietnamese and Jewish; he needs to focus more on being a philosophy major at Pomona.’ And I said, ‘Damn, I thought I was giving the people what they want.’ You can’t please everybody.”

PETER WERMUTH ’01: AMBASSADOR OF BASEBALL

Peter Wermuth ’00 is trying to get cricket nation excited about that other bat-and-ball sport. Sent by Major League Baseball to oversee the six-team Australian Baseball League as CEO, Wermuth was first exposed to hardball as a kid growing up in Germany. He played on the Pomona-Pitzer squad and coached on the German national team before heading to the big-league boardroom.

Peter Wermuth ’00 is trying to get cricket nation excited about that other bat-and-ball sport. Sent by Major League Baseball to oversee the six-team Australian Baseball League as CEO, Wermuth was first exposed to hardball as a kid growing up in Germany. He played on the Pomona-Pitzer squad and coached on the German national team before heading to the big-league boardroom.

I started playing baseball at age 10—my older brother went to college in America and brought some equipment back to Germany. We had no clue what we were doing: our first time out, we went to a schoolyard and set up a field with two bases and home plate.

The catalyst for me was attending my first German-American Baseball League game in Mainz, my hometown. It was a great atmosphere: a big barbecue going, old men playing dominos on the side of the field, people playing music and even some Latin dancing.

There wasn’t any German youth baseball in the country at the time, but the U.S. Armed Forces ran its own Little League, which I joined. I’d travel from one military base to another, competing against American teams and gradually losing some of my German accent. When I was 12, I applied to be the club’s treasurer; they wouldn’t let me, which I didn’t think was reasonable at all, so I went off and started my own club.

I wanted to attend college in the U.S. All the other top liberal arts schools were in the Northeast, and with baseball being a big part of the decision, [Pomona] was an easy choice. At Columbia Business School, I ran the Sports Business Association and brought an M.L.B. executive to campus. After the talk he asked me what I was planning to do that summer and I told him, “I’m going to work for you.” I did—and have been since.

I always knew I wanted to set up a professional league. Baseball in most countries outside the U.S. is not the national sport. It’s difficult for an American to understand that ‘if you build it’ they will not necessarily come! In Australia there’s cricket, rugby union, rugby league, Australian-rules football. You have to treat baseball as a niche sport. That’s something I bring to the table because I lived in that sort of environment in Germany.

We’re hoping to reach that second tier [in Australia]. My U.S. experiences inspired me to use what I think of as the minor league model, where it’s framed as a fun family night out. Exciting promotions, mascots, upbeat music, a safe environment—baseball is almost secondary.

I’d love to grow the league as fast as possible, but we don’t want the resources that we put in to exceed demand. It’d be a disaster to play in venues that we can’t fill. Though we’ll never be cricket or the Australian Football League, I think we can establish a really attractive product. This is likely the last chance baseball has to establish itself as a relevant sport in Australia, and I feel great responsibility for the future of the sport in this country.

ANBINH PHAN ’01: CREATIVE EMPATHY

Anbinh Phan ’01 was born in a refugee camp in Malaysia after her parents fled Vietnam by boat during the exodus of the late ’70s. The family eventually settled in Torrance, Calif. After graduating from Pomona, Phan earned an M.P.A. from Princeton and a law degree from Georgetown, and now she is starting a social-justice venture revolving around stateless persons and human trafficking victims in Southeast Asia. Her work has spurred her to reflect on her family’s risky journey to America. In the photo, Phan holds a shapshot of herself with her mother at the refugee camp in Malaysia.

Anbinh Phan ’01 was born in a refugee camp in Malaysia after her parents fled Vietnam by boat during the exodus of the late ’70s. The family eventually settled in Torrance, Calif. After graduating from Pomona, Phan earned an M.P.A. from Princeton and a law degree from Georgetown, and now she is starting a social-justice venture revolving around stateless persons and human trafficking victims in Southeast Asia. Her work has spurred her to reflect on her family’s risky journey to America. In the photo, Phan holds a shapshot of herself with her mother at the refugee camp in Malaysia.

My parents worked really hard in Torrance. We lived modestly so that they could send money home to Vietnam. At Pomona, my whole experience made me think much more deeply about self-identity, Christian faith and civil rights. Having that multidisciplinary education helped me start to see things through numerous lenses.

I focused on international trade after graduating: I did a fellowship in Vietnam for eight months and worked at the U.S. Treasury for several years. I got interested in human rights, since a huge part of international trade revolves around labor, the supply chain and how products are manufactured.

In the summer after my second year of law school in 2009, I worked for [the human rights organizations] Global Centurion and Boat People S.O.S. in Southeast Asia, and met human trafficking survivors in shelters and asylums in Thailand, Vietnam and Malaysia. I only got glimpses of their lives, but they made a big impression on me, and I realized these people have aspirations like my family. They just want to create better futures for themselves.

During the trip I returned to Pulau Tengah, the Malaysian refugee camp I was born in, which was an amazing experience. To me it was this mythical place where my family had put so many hopes after surviving war and poverty. They were so brave to leave their country and have a child in the middle of the ocean. It wasn’t a coincidence that my name means “peace” in Vietnamese—that’s what my parents hoped for me on these shores.

When I came back to law school, I couldn’t get the experience out of my mind, and I started devoting my research to that region. Even though I’m American, I can relate as a member of the Vietnamese diaspora—I speak the language and understand the pressures and fears they face. It’s a natural empathy.

I feel privileged to be in America. I always wanted to pursue public service, because I didn’t want my family to work for all these things just so I could benefit individually. My ultimate dream is for these people I’m trying to help to gain some sense of optimism about their future. I’ve not seen the things I’m doing accomplish that yet, but I deeply hope that’s where we’ll be soon enough.

Recently, I presented at the United Nations Special Rapporteur on Human Rights in Cambodia. It was an opportunity to emphasize the challenges stateless people face—no access to education or social services, and a high vulnerability to labor and sex trafficking—as well as to advocate for a solution. As much as it was about legal rights, it was also a human story. It was fulfilling to share information to empathetic ears; the stories we chose to tell reflect who we are and what we hope for in the world.

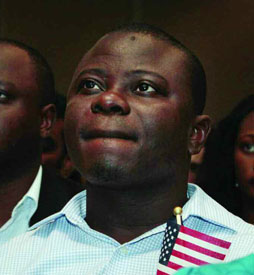

The Ecksteins’ journey “from sea to shining sea” began at the end of January in San Diego and will end in New York City in June. By that time, Eckstein, a semi-retired physician from Phoenix, Ariz., will have racked up 3,500 miles by bike and on foot while Diane, a Citizenship Counts board member, follows in a small RV with their dog Kipp. “We wanted Gerda to see this journey,” says Eckstein, “which we view as a journey of freedom and hope.”

The Ecksteins’ journey “from sea to shining sea” began at the end of January in San Diego and will end in New York City in June. By that time, Eckstein, a semi-retired physician from Phoenix, Ariz., will have racked up 3,500 miles by bike and on foot while Diane, a Citizenship Counts board member, follows in a small RV with their dog Kipp. “We wanted Gerda to see this journey,” says Eckstein, “which we view as a journey of freedom and hope.”

Next, a student-led discussion focuses on I’m Working on That: A Trek from Science Fiction to Science Fact by William Shatner and Chip Walter, and covers topics ranging from wearable computers and biowarfare to cryogenics and virtual reality.

Next, a student-led discussion focuses on I’m Working on That: A Trek from Science Fiction to Science Fact by William Shatner and Chip Walter, and covers topics ranging from wearable computers and biowarfare to cryogenics and virtual reality. Tanenbaum: How many people do you see wearing their earpieces 24 hours a day, seven days a week? I think we’re already there. I want to ask a question that gets at both virtual reality and the wearable computers.

Tanenbaum: How many people do you see wearing their earpieces 24 hours a day, seven days a week? I think we’re already there. I want to ask a question that gets at both virtual reality and the wearable computers.

For Aldo Ramirez ’00, school was an escape from a hard life toiling in the orchards and fields as a young boy. So, it is no surprise that after graduating from Pomona, he pursued a career in education. He is now putting his experience to work by helping young, low-income immigrants as principal of a small elementary school in the city of San Bernardino.

For Aldo Ramirez ’00, school was an escape from a hard life toiling in the orchards and fields as a young boy. So, it is no surprise that after graduating from Pomona, he pursued a career in education. He is now putting his experience to work by helping young, low-income immigrants as principal of a small elementary school in the city of San Bernardino. Joe Nguyen ’05 grew up in the Deep South as the son of immigrant parents whose roots stretch from Germany and Austria to Vietnam. So, perhaps it’s only natural that he decided to become a stand-up comedian. Nguyen holds on to his day job working for the state of California and does standup at night in Los Angeles and San Francisco.

Joe Nguyen ’05 grew up in the Deep South as the son of immigrant parents whose roots stretch from Germany and Austria to Vietnam. So, perhaps it’s only natural that he decided to become a stand-up comedian. Nguyen holds on to his day job working for the state of California and does standup at night in Los Angeles and San Francisco. Peter Wermuth ’00 is trying to get cricket nation excited about that other bat-and-ball sport. Sent by Major League Baseball to oversee the six-team Australian Baseball League as CEO, Wermuth was first exposed to hardball as a kid growing up in Germany. He played on the Pomona-Pitzer squad and coached on the German national team before heading to the big-league boardroom.

Peter Wermuth ’00 is trying to get cricket nation excited about that other bat-and-ball sport. Sent by Major League Baseball to oversee the six-team Australian Baseball League as CEO, Wermuth was first exposed to hardball as a kid growing up in Germany. He played on the Pomona-Pitzer squad and coached on the German national team before heading to the big-league boardroom. Anbinh Phan ’01 was born in a refugee camp in Malaysia after her parents fled Vietnam by boat during the exodus of the late ’70s. The family eventually settled in Torrance, Calif. After graduating from Pomona, Phan earned an M.P.A. from Princeton and a law degree from Georgetown, and now she is starting a social-justice venture revolving around stateless persons and human trafficking victims in Southeast Asia. Her work has spurred her to reflect on her family’s risky journey to America. In the photo, Phan holds a shapshot of herself with her mother at the refugee camp in Malaysia.

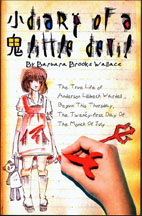

Anbinh Phan ’01 was born in a refugee camp in Malaysia after her parents fled Vietnam by boat during the exodus of the late ’70s. The family eventually settled in Torrance, Calif. After graduating from Pomona, Phan earned an M.P.A. from Princeton and a law degree from Georgetown, and now she is starting a social-justice venture revolving around stateless persons and human trafficking victims in Southeast Asia. Her work has spurred her to reflect on her family’s risky journey to America. In the photo, Phan holds a shapshot of herself with her mother at the refugee camp in Malaysia. If you’re reading James Thurber and Robert Benchley and composing comedic poetry at the tender age of 7, then writing a book that examines humor from every conceivable angle doesn’t feel like that much of a stretch. Indeed, when David Misch ’72 began putting together Funny: The Book three years ago, it felt like the next logical step in a four-decade career that has included stints as a comedic folk singer, stand-up comedian and writer for such shows as Mork and Mindy and Saturday Night Live.

If you’re reading James Thurber and Robert Benchley and composing comedic poetry at the tender age of 7, then writing a book that examines humor from every conceivable angle doesn’t feel like that much of a stretch. Indeed, when David Misch ’72 began putting together Funny: The Book three years ago, it felt like the next logical step in a four-decade career that has included stints as a comedic folk singer, stand-up comedian and writer for such shows as Mork and Mindy and Saturday Night Live. Before moving on, Pomona’s Class of 2012 first had to move merchandise and shed accessories. So, for weeks before this year’s Commencement, the daily Student Digester turned into a swap meet laden with “SENIOR SALES!” We looked past the expected futons and floor lamps for the finer things, listed here with the original asking price:

Before moving on, Pomona’s Class of 2012 first had to move merchandise and shed accessories. So, for weeks before this year’s Commencement, the daily Student Digester turned into a swap meet laden with “SENIOR SALES!” We looked past the expected futons and floor lamps for the finer things, listed here with the original asking price: • Chin-up bar: $15

• Chin-up bar: $15 But she hasn’t forgotten her shaky start. Wallace, who today lives in a retirement home in McLean, Va., credits her success to an initially-nerve-wracking encounter with her freshman-year English professor at Pomona College.

But she hasn’t forgotten her shaky start. Wallace, who today lives in a retirement home in McLean, Va., credits her success to an initially-nerve-wracking encounter with her freshman-year English professor at Pomona College.