This noteworthy letter from Andrew Hoyem ’57 appears in our spring issue, which will soon hit mailboxes and appear online:

When the great jazz composer and pianist Dave Brubeck died on Dec. 5, 2012, a day short of his 92nd birthday, some members of the Class of 1957 reminisced about their having sponsored a concert by the Brubeck quartet in Little Bridges 58 years earlier.

This was mainly the doing of our classmate Marvin Nathan, who was a big fan of Brubeck and had gotten to know the members of the quartet the summer after our freshman year, in 1954, when the musicians had a three-month gig at Zardi’s in Hollywood. Nathan went to the club nightly during the vacation and returned to college full of enthusiasm for the new style of jazz played by Brubeck. Marvin recounts: “That Christmas I gave the four of them their first matching set of ties, handkerchiefs and cuff links, which, I think, they wore at the Pomona concert.” He made the arrangements directly with Brubeck, and a committee of the Class of ’57 was formed to produce the concert. Brubeck was the first to play college dates, lifting jazz out of smoke-filled clubs. Those were simpler times: no agent or manager or record company was intermediary. We just asked Brubeck, and later, for another concert sponsored by the class, Andre Previn; they said yes, turned up with their sidemen and played and got paid.

But paying the musicians required a paying audience. Steve Glass ’57 and subsequently professor of classics at Pitzer College, recalls that early ticket sales for the Brubeck concert were going slowly. His classmate and future wife Sandy was in charge of publicity and she was worried. In those days, West Coast/Cool Jazz was a relatively arcane phenomenon. Then, shortly before the concert, the Nov. 8, 1954 issue of Time magazine had Dave Brubeck on the cover, only the second jazz musician to be so featured (after Louis Armstrong), and the place was packed.

But paying the musicians required a paying audience. Steve Glass ’57 and subsequently professor of classics at Pitzer College, recalls that early ticket sales for the Brubeck concert were going slowly. His classmate and future wife Sandy was in charge of publicity and she was worried. In those days, West Coast/Cool Jazz was a relatively arcane phenomenon. Then, shortly before the concert, the Nov. 8, 1954 issue of Time magazine had Dave Brubeck on the cover, only the second jazz musician to be so featured (after Louis Armstrong), and the place was packed.

For the program I drew caricatures of the musicians: Brubeck (piano), Paul Desmond (alto sax), Bob Bates (bass) and Joe Dodge (drums). Marvin Nathan wrote the notes. Reflecting on the concert, he writes: “We caught the group at its acme, in the wake of the remarkable recordings of Jazz at Storyville and Jazz at Oberlin, which, for my money, are the two greatest albums Dave and Paul ever did.”

Marvin left Pomona after two years to study jazz saxophone at the San Francisco Conservatory of Music but decided the instrument should be left to the likes of John Coltrane and instead became a humanities professor. All of us amateur promoters remained jazz aficionados. Why, just this morning I refolded my fedora into a pork-pie hat and set off looking the hepcat I wished to be.

— Andrew Hoyem ’57

The O.J. flowing in campus dining halls these days doesn’t come from frozen concentrate, nor was it born thousands of miles away in Florida.

The O.J. flowing in campus dining halls these days doesn’t come from frozen concentrate, nor was it born thousands of miles away in Florida. Trees, Ph.D.s and … country? Claremont is a long way from Nashville, but this school year brings two country superstars to

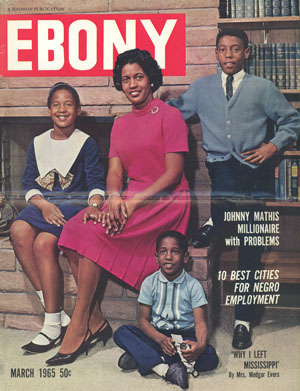

Trees, Ph.D.s and … country? Claremont is a long way from Nashville, but this school year brings two country superstars to  This year marks the 50th anniversary of the assassination of her husband, civil rights activist Medgar Evers, who was shot in the back outside their Jackson, Miss., home on the morning of June 12, 1963, while Myrlie and their three children were inside.

This year marks the 50th anniversary of the assassination of her husband, civil rights activist Medgar Evers, who was shot in the back outside their Jackson, Miss., home on the morning of June 12, 1963, while Myrlie and their three children were inside. Laszlo Bock ’93 is senior vice president of people operations at Google, leading the attraction, development and retention of “Googlers.” He also leads or has led various business groups at Google, including the services group, technology and operations and other areas. At Pomona, Bock majored in international relations, and served as a residence hall sponsor and in student government and Mortar Board. Bock, who lives in the Bay Area, has an M.B.A. from the Yale School of Management, and has testified before Congress on immigration reform and labor issues. In 2010, he was named “Human Resources Executive of the Year” by HR Executive Magazine.

Laszlo Bock ’93 is senior vice president of people operations at Google, leading the attraction, development and retention of “Googlers.” He also leads or has led various business groups at Google, including the services group, technology and operations and other areas. At Pomona, Bock majored in international relations, and served as a residence hall sponsor and in student government and Mortar Board. Bock, who lives in the Bay Area, has an M.B.A. from the Yale School of Management, and has testified before Congress on immigration reform and labor issues. In 2010, he was named “Human Resources Executive of the Year” by HR Executive Magazine. Sam Glick ’04 is an associate partner at Oliver Wyman, a leading global management consulting firm, advising clients in the healthcare and life sciences industries. An economics major and classics minor at Pomona, Glick graduated with distinction, and as a student was ASPC academic affairs commissioner, judiciary council chair, member of the presidential search and senior class gift committees, and a director of the Claremont Community Foundation. Glick previously served on the board as young alumni trustee from 2007 to 2011. He lives in San Francisco with his wife, Emily (George) Glick ’04.

Sam Glick ’04 is an associate partner at Oliver Wyman, a leading global management consulting firm, advising clients in the healthcare and life sciences industries. An economics major and classics minor at Pomona, Glick graduated with distinction, and as a student was ASPC academic affairs commissioner, judiciary council chair, member of the presidential search and senior class gift committees, and a director of the Claremont Community Foundation. Glick previously served on the board as young alumni trustee from 2007 to 2011. He lives in San Francisco with his wife, Emily (George) Glick ’04. A trustee since 1999, Buckley could have reasonably expected to be winding down, pulling back a bit, as she completes the final few years of her term. Instead, the Santa Rosa, Calif., resident agreed to step up to the role of board chair.

A trustee since 1999, Buckley could have reasonably expected to be winding down, pulling back a bit, as she completes the final few years of her term. Instead, the Santa Rosa, Calif., resident agreed to step up to the role of board chair.