Eric Myers ’80 was placing flags on graves for Memorial Day with his daughter’s church youth group when he encountered a solemn Pomona connection 3,000 miles from campus. Poughkeepsie Rural Cemetery in New York is the resting place for members of the Smiley family, including Albert K. Smiley, the Pomona trustee of the late 1800s whose name is on one of Pomona’s oldest residence halls, where Myers lived his junior year. Today, Myers, who had come across the grave years ago but didn’t remember the exact spot, works at SUNY New Paltz, home to Smiley Art Building, named for the family whose philanthropy supported colleges and civic enterprises on both coasts.

Eric Myers ’80 was placing flags on graves for Memorial Day with his daughter’s church youth group when he encountered a solemn Pomona connection 3,000 miles from campus. Poughkeepsie Rural Cemetery in New York is the resting place for members of the Smiley family, including Albert K. Smiley, the Pomona trustee of the late 1800s whose name is on one of Pomona’s oldest residence halls, where Myers lived his junior year. Today, Myers, who had come across the grave years ago but didn’t remember the exact spot, works at SUNY New Paltz, home to Smiley Art Building, named for the family whose philanthropy supported colleges and civic enterprises on both coasts.

Articles Written By: Staff

Solemn Surprise

Quoted

“I came late to bicycle riding.

“I came late to bicycle riding.

When I first learned or tried to learn, I rode myself straight into the back of a car and didn’t pick up a bike for maybe three years after that.”

—Ken McCloud ’07,

who today is policy director for the League of American Bicyclists, appearing on the Sagecast.

Book Talk: Vivid Quest

Adam Rogers ’92 showed his first glimmer of interest in the mysteries of color perception with a middle school science project. He simply colored in a square on a piece of paper, held it up and asked the class, “What color do you see?”

Adam Rogers ’92 showed his first glimmer of interest in the mysteries of color perception with a middle school science project. He simply colored in a square on a piece of paper, held it up and asked the class, “What color do you see?”

Most students saw red, but one replied, “Pink.” Decades later, the science writer delves deeper into the ways that humans relate to color in his new book, Full Spectrum: How the Science of Color Made Us Modern. Here he explains a bit about how the book began, what he learned while writing it and what science journalism is like today.

PCM: Where did the idea for a book about the science of color come from?

Adam Rogers: As a science reporter at Newsweek in the ’90s, I found out about this pigment, this one molecule, this one chemical called titanium dioxide. It makes the color white.

It’s the super-light metal that you make artificial hips and Soviet-era submarines out of. Titanium, you take one atom of that, two atoms of oxygen, you stick those together and you get this stuff with a super-high refractive index, very opaque, very bright. And when you make it into a powder, if you do the right chemistry on it, you can make the color white, and it also becomes a ubiquitous chemical in all of the things around [us]. It’s in a lot of different kinds of paints; it’s in paper; it’s in a lot of plastics; it’s in pills and some foods.

I got obsessed with this idea that there was this one thing that was just everywhere—and essentially invisible. Except that it was also a color. I couldn’t shake that.

PCM: How long did it take you to write the book, and what are some of the places that it took you?

Adam Rogers: From the time I said, “OK, it’s going to be a book” to now is, I think, four years. I was late; I ran late on it. I went to the place in Cornwall, in England, where titanium was discovered, where somebody first identified that there was some new element in the dirt in the bed of a creek. I spent some time wandering around museums in Paris trying to see the colors instead of just seeing the art. I went to a professional coding conference in Indianapolis and tried to talk to the people who use color to put on things like cars.

There was some time spent in university labs, talking to folks about their research looking into the brains of monkeys and trying to understand what happens in those brains when they see color. In Boston I was talking to folks about trying to 3D print or paint forgeries of paintings that would be indistinguishable from the actual painting because of the way that they responded to the color around them.

PCM: Early in the book you write about color perception and tiny microbes and the possible origin of color perception. Can you tell us about that?

Adam Rogers: There has to be some early example of life that first started to be able to see color…[maybe] a totally different branch of life on the tree that’s billions of years old that would have been the first living things on Earth that turn out to have been able to distinguish between basically blue light and red light. Because one of those [colors] would have told them how to hide, and one of them would have been a place where they could hunt, where they could go look for food.

To do that, those critters had to develop the pigments that would respond differently, that would send a signal inside their own little single cells that would say either, “OK, now we’re getting this one wavelength; go toward it,” or “Now we’re getting this other wavelength; go away from it.” So the question then is how did they evolve that [ability]? The hypothesis is that it began as a form of photosynthesis—that you develop these very complicated molecules, versions of which still exist today in plants, that will be able to use the photons coming into the bodies of these microorganisms, of these microbes.

PCM: Do you ever find yourself out of your scientific depth?

Adam Rogers: All the time. I have no scientific depth in some respects. My formal science training was at Pomona, and that was it. I was a science, technology and society major. I have slightly more than half of a biology degree [and studied a lot of] history. That turned out to be really meaningful, because I find myself still writing STS stuff. Somebody had to point it out to me, that I’m still doing STS.

PCM: With the degree of science denial and the politicization of science and the general lack of scientific literacy in America today, it must be frustrating. Do you run up against that as a writer?

Adam Rogers: I do. Ten years ago I would have said, “Well, it’s on me to make sure that people understand my writing.…People won’t know what I’m necessarily talking about from the jump, and I have to compel them to come into a story and give them reasons to keep reading and then explain to them stuff that’s right and true.” I still think all of that. I think that some of this [science denial or limited scientific literacy] is the media’s fault, but some of it’s not. People have so little understanding now not only about science and the way that you might learn it in a classroom, but also about just who scientists are…and how you know something is maybe more true than something else. Societally, we have been terrible at explaining that to people. We don’t really teach it, we don’t really make it a priority, and I think we’re reaping some of that now.

PCM: What advice do you have for young people out there who are interested in pursuing a career in science writing?

Adam Rogers: I hope that they will. It is a hard time in journalism now, for social reasons and economic reasons. But I remain optimistic that even if the kind of places that do journalism will change, there still will be places to do journalism, and I think that writing about science—don’t tell any of my colleagues—I think it’s the most important beat. Don’t tell anybody I said that.

—Abridged and adapted from Sagecast, the podcast of Pomona College

Eager Readers

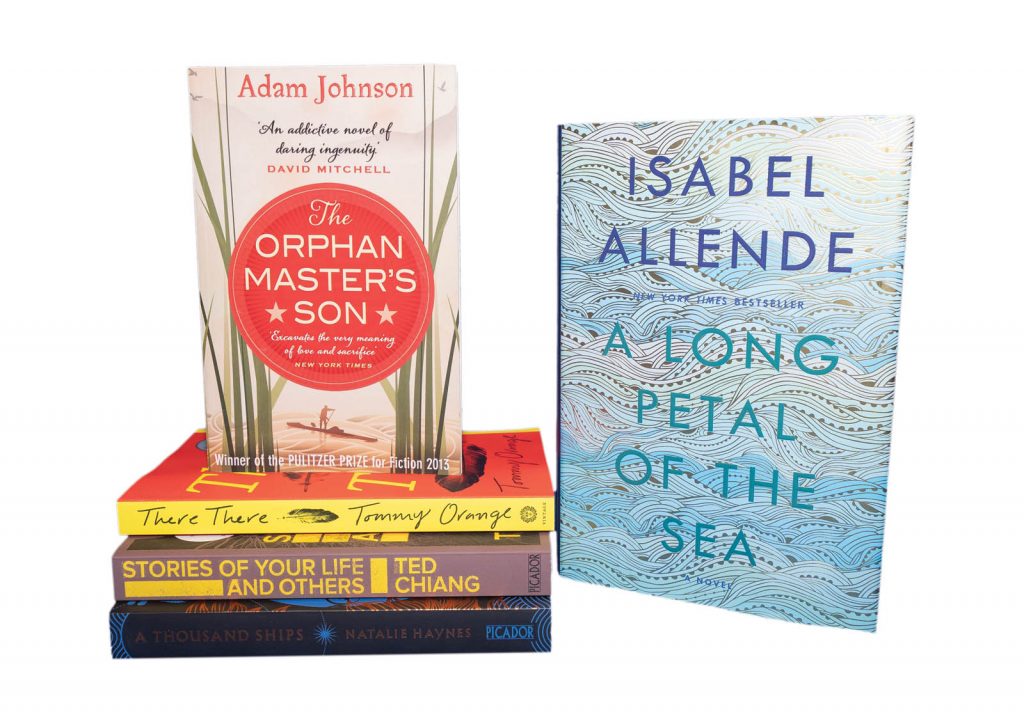

Sagehens have always been proudly bookish, so it is no surprise the admissions team’s decision to send a handpicked tome to each U.S. student admitted in spring went over well, winning raves on social media. “Pomona is amazing,” wrote one poster on Reddit. “They keep winning my heart.”

Sagehens have always been proudly bookish, so it is no surprise the admissions team’s decision to send a handpicked tome to each U.S. student admitted in spring went over well, winning raves on social media. “Pomona is amazing,” wrote one poster on Reddit. “They keep winning my heart.”

“Our goal was to send a personalized mailing that, in a way, assured students we had indeed read their applications, and, most importantly, really seen them and their interests,” says Paola Reyes Noriega, assistant dean of admissions.

The eight books were recommendations from College staff or were works by guest speakers the College has recently welcomed, such as There There author Tommy Orange. Admissions officers picked which one to send based on what they learned about the admitted students in applications, offering the perfect way for soon-to-be Sagehens to open a new chapter at Pomona.

Not Pictured: Make Your Home Among Strangers by Jennine Capó Crucet, Real Life by Brandon Taylor and The Vanishing Half by Britt Bennett

Bookmarks Fall/Winter 2021

The Thousand Crimes of Ming Tsu

The Thousand Crimes of Ming Tsu

The debut novel by Tom Lin ’18, a New York Times Book Review Editor’s Choice selection, is a reinvention of the American Western, this time starring a Chinese American assassin.

Someone to Watch Over Me

Someone to Watch Over Me

Set in 1947 Hollywood, this mystery thriller by Dan Bronson ’65 follows an actor turned studio publicist tasked with finding a missing actress.

Japan’s Aging Peace: Pacifism and Militarism in the Twenty-First Century

Japan’s Aging Peace: Pacifism and Militarism in the Twenty-First Century

Politics Professor Tom Phuong Le posits that Japan’s reluctance to remilitarize is due to factors of demographics, culture and perspectives on security.

Bird versus Bulldozer: A Quarter-Century Conservation Battle in a Biodiversity Hotspot

Bird versus Bulldozer: A Quarter-Century Conservation Battle in a Biodiversity Hotspot

Using the story of the coastal California gnatcatcher, ecologist Audrey L. Mayer ’94 offers an optimistic perspective on regional conservation planning strategies benefiting both humans and wildlife.

Building the Population Bomb

Building the Population Bomb

Emily Klancher Merchant ’01 writes the history of U.S. demography and population control, challenging the conventional notion that population growth in and of itself is inherently a problem.

Control the Narrative: The Executive’s Guide to Building, Pivoting and Repairing Your Reputation

Control the Narrative: The Executive’s Guide to Building, Pivoting and Repairing Your Reputation

Lida Citroën ’86 writes about the power of personal branding and offers advice on how to make your reputation an asset.

Parabellum

Parabellum

In this crime novel by Greg Hickey ’08, four individuals emerge as possible suspects in a deadly mass shooting in Chicago.

Project Inferno (Infiltration)

Project Inferno (Infiltration)

William W. King ’70 has penned a futuristic novel (the first in a series) about an ordinary household object that is weaponized to attack America.

Ruminations on a Parrot Named Cosmo

Ruminations on a Parrot Named Cosmo

Betty Jean Craige ’68 was inspired by her African grey parrot to write 75 short humor essays about her pet’s language learning, animal consciousness and the cognitive similarities between parrots and humans.

The Mindfulness Sidekick: Mental Wellness to Maximize Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation

The Mindfulness Sidekick: Mental Wellness to Maximize Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation

For individuals with long-term depression, Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS) is widely considered a breakthrough treatment, and in this book Amy Halloran-Steiner ’94 journeys with patients, teaching the medicine of mindfulness.

Water Music: Adventures of a Journeyman Surfer

Water Music: Adventures of a Journeyman Surfer

David Rearwin ’62 started surfing 70 years ago. At the age of 80, he continues—and chronicles—his escapades at sea.

Time in Maps: From the Age of Discovery to Our Digital Era

Time in Maps: From the Age of Discovery to Our Digital Era

Historian Caroline Winterer ’88 is co-editor of a volume that examines how maps from across the world have depicted time in inventive ways.

Tattoo on My Brain: A Neurologist’s Personal Battle Against Alzheimer’s Disease

Tattoo on My Brain: A Neurologist’s Personal Battle Against Alzheimer’s Disease

Dr. Daniel Gibbs ’73 offers a memoir about his diagnosis of Alzheimer’s—the very disease he treated in patients for 25 years.

Out of Print: Mediating Information in the Novel and the Book

Out of Print: Mediating Information in the Novel and the Book

Julia Panko ’02 examines how the print book has fared with the proliferation of data across the 20th and 21st centuries.

Faculty Retirees

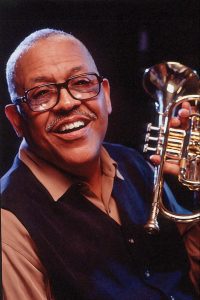

Bobby Bradford

Bobby Bradford

lecturer in music

44 years at Pomona

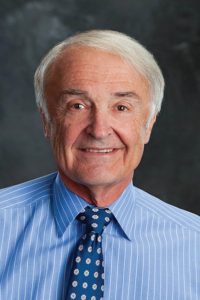

Everett L. “Rett” Bull Jr.

Everett L. “Rett” Bull Jr.

Osler-Loucks Professor in Science and professor of computer science,

42 years at Pomona

Ann Davis

Ann Davis

McConnell Professor of Human Relations and professor of philosophy

22 years at Pomona

Stephen A. Erickson

Stephen A. Erickson

Wilson Lyon Professor of the Humanities and professor of philosophy

56 years at Pomona

Erica Flapan

Erica Flapan

Lingurn H. Burkhead Professor of Mathematics

34 years at Pomona

Sherry Linnell

Sherry Linnell

resident designer and professor of theatre

45 years at Pomona

Lynne K. Miyake

Lynne K. Miyake

professor of Japanese

32 years at Pomona

Helena Wall

Warren Finney Day Professor of History

36 years at Pomona

Jianhsin Wu

Jianhsin Wu

adjunct professor of Asian languages and literatures

30 years at Pomona

Richard “Rick” Worthington

Richard “Rick” Worthington

professor of politics

30 years at Pomona

New Registrar

Erin Michelle Collins

The College’s new registrar, Erin Michelle Collins, started in July and comes to Pomona after serving in the same role at California Institute of the Arts. Prior to CalArts, Collins worked in positions of increasing responsibility within admissions and records at the University of La Verne, Victor Valley College and Barstow Community College.

Collins holds a bachelor’s degree in social psychology from Park University in Missouri and a master’s in psychology from The Chicago School of Professional Psychology. She arrives at Pomona a century after Charles Tabor Fitts became Pomona’s first full-time registrar in 1921, at a time when enrollment was just over 700 students and The Claremont Colleges consortium was yet to exist.

Today, Collins says, registrars’ work reaches beyond student and academic records management to include running student information systems and providing data that drives policy and improves student success. Most importantly, “a registrar has to be service-oriented, as retention and student success is directly related to how connected a student feels to their institution,” says Collins, “As the registrar, I can directly impact this connection.”

Wig Awards

Every year, juniors and seniors nominate professors for the Wig Awards, Pomona College’s highest honor for excellence in teaching, concern for students, and service to the College and community. During an extraordinary year of remote instruction due to the COVID-19 pandemic, six faculty members were elected by juniors and seniors and confirmed by a committee of trustees, faculty and students.

The 2021 recipients are:

- Eleanor Birrell,

assistant professor of computer science - Erica Dobbs,

assistant professor of politics - Phyllis Jackson,

associate professor of art history - Joanne Nucho,

assistant professor of anthropology - Kara Wittman,

assistant professor of English - Yuqing Melanie Wu,

professor of computer science

Eleanor Birrell

Erica Dobbs

Phyllis Jackson

Joanne Nucho

Kara Wittman

Yuqing Melanie Wu

Each of this year’s recipients is a first-time winner, except for Jackson, who was previously honored in 2003, 2010 and 2015.

How to Move a Museum

Workers survey the 30-foot sculpture ghandiG by Peter Shelton ’73 at the museum’s former location before moving it by crane across College Avenue to its new home.

Drivers who regularly ventured past the Pomona College campus in the early mornings of October and November 2019 likely witnessed a strange ritual at the intersection of Bonita and College avenues.

Day after day, a procession of student interns crossed the street, slowly rolling stainless-steel restaurant-style carts loaded with slate-gray boxes tied down with brightly colored bungees. Motorists waited as the parade carefully bypassed the myriad yellow warning bumps near the curbs. Reaching the other side, the interns gently maneuvered the carts up to the sidewalk and then onto the ramp of the newly completed Benton Museum of Art at Pomona College.

The museum collection was arriving at its new home. Finally.

For many people, the words “Moving Day” trigger fear and apprehension from beginning to end: the monumental chaos of sorting and packing items, the crucial task of hiring a trustworthy moving team and the suspense mixed with dread of opening boxes at the new location, hoping for minimal damage. But for the staff at the Benton, “Moving Day” was a welcomed phrase for a transition that was long overdue and took nearly two years to complete.

Intern Emily Petro ’21 sorts and labels arrowheads from the Native American Collection.

When news of the 2017 groundbreaking for the spacious new $44 million state-of-the-art museum at the southwest corner of Bonita and College was announced, there was a cheer of relief that all objects in the museum collection would be under one roof at last. For more than 10 years, as many as 13,000 objects in the growing collection had been spread out in three satellite venues: Montgomery Art Gallery, Rembrandt Hall and Bridges Auditorium. The Native American Collection, first assembled around the turn of the 20th century, occupied various locations—among them the basement of the humanities building at Scripps College, then Sumner Hall, and in 2011 the lower level of Bridges.

Celebration quickly dissolved into the electric hum of brainpower as staff began to strategize. Here was a chance to do an up-to-date inventory of every collection item before safely packing and transporting objects as diverse as Andy Warhol Polaroids, Goya etchings, alabaster bas-relief sculptures, large abstract paintings, beaded Sioux leggings and contemporary art by Pomona alumni, including Helen Pashgian ’56 and Chris Burden ’69.

Such an inventory had never been done before.

Workmen prepare to move ghandiG by Peter Shelton

“I had been warned by colleagues that moving a collection is the single most difficult and yet rewarding task a registrar could ever undertake,” says Steve Comba, associate director/registrar at the Benton—who already had twice overseen moves of the Native American Collection.

Objects didn’t have to travel physically far—all satellite locations were blocks or buildings away—but that didn’t make the task less daunting. Handling objects at any step of the process is always a risk, says Comba. “There’s always the possibility of human error. We wanted to do this right. We had to take our time.”

Objects didn’t have to travel physically far—all satellite locations were blocks or buildings away—but that didn’t make the task less daunting. Handling objects at any step of the process is always a risk, says Comba. “There’s always the possibility of human error. We wanted to do this right. We had to take our time.”

Comba brought on board independent collections manager Karen Hudson, who assumed duties as move coordinator/registrar. “Before you move anything, you need to know what you have,” she says about the time-consuming and labor-intensive process of creating the inventory. “You start by opening up every box, in every storage room and in every building. I had my eye on every single object in the collection.”

Comba brought on board independent collections manager Karen Hudson, who assumed duties as move coordinator/registrar. “Before you move anything, you need to know what you have,” she says about the time-consuming and labor-intensive process of creating the inventory. “You start by opening up every box, in every storage room and in every building. I had my eye on every single object in the collection.”

Going through hanging racks, cabinetry and Solander storage boxes one by one for almost a year, Hudson compared each item to its own unique catalog number, cross-checked the database and updated all pertinent information. She noted items with missing numbers, objects that had been numbered incorrectly and other discrepancies.

“You don’t want to move problems,” sums up Hudson. “You solve them first before you pack them up.”

As with any move, surprises were uncovered. For years Comba thought that a rare Sioux ceremonial rattle had been lost; he was thrilled when the beautifully quillworked and beaded treasure was discovered during the inventory. Another surprise: The museum’s collection grew from 11,000 objects pre-inventory to nearly 13,000 in late 2018. (Note: Because of additional gifts to the collection since 2018, that number is now officially 16,000.)

The first museum piece arrived at its new home in spring of 2019.

In the early morning of March 22, spectators watched a 30-foot-tall bronze sculpture dangle from a hoist and crane that was inching its way down College Avenue. No trees or overhead wires blocked the transit. Under a blue sky, there was just a steady progression forward: ghandiG was on the move.

Purchased by the college in 2006, the ethereal sculpture by Pomona alumnus Peter Shelton ’73 was making its way to a new home amid the landscape of the Benton, which was still a work in progress at the time.

Moving ghandiG involved crews severing the sculpture’s support cabling system at the old location, transporting the artwork two blocks and then installing it—with new cabling—at the prominent corner. Shelton was consulted about the proper orientation for his sculpture, which now welcomes visitors to the museum in a striking way.

While ghandiG was officially the first piece of art to be moved to the Benton, it would be months before the rest of the collection joined the sculpture at the new location. Transporting those other items was far less dramatic—but there were still some heart-pounding moments.

The process involved the meticulous packing of hundreds of paintings, pottery works, photos and more. Comba, Hudson and a third member of the museum staff were joined by a team of interns Hudson described as invaluable. “We needed their help, their youthful stamina and enthusiasm,” she says. Comba goes further, calling them “rock stars.” He adds that the collection-moving interns weren’t all art history majors. “We had conservation majors from Scripps College and athletes from Pomona,” he says. “They each brought their own skills to the project.”

The museum could have hired an expensive professional art-moving company for the entire job, but since the Benton is a teaching museum with a robust internship program, the collection move presented an exceptional chance for hands-on, behind-the-scenes, roll-up-your-sleeves learning. Twelve interns—among them Pomona students Nina Mueller ’19, Ethan Dieck ’22, Jem Stern ’22, Quin Fraley ’22, Katherine Purev ’23 and Emily Petro ’21—stepped up for a challenge that lasted from April 2019 to March 2020.

The museum could have hired an expensive professional art-moving company for the entire job, but since the Benton is a teaching museum with a robust internship program, the collection move presented an exceptional chance for hands-on, behind-the-scenes, roll-up-your-sleeves learning. Twelve interns—among them Pomona students Nina Mueller ’19, Ethan Dieck ’22, Jem Stern ’22, Quin Fraley ’22, Katherine Purev ’23 and Emily Petro ’21—stepped up for a challenge that lasted from April 2019 to March 2020.

The Native American collection was the first to be physically moved; it was the farthest from the new museum (although still only a few blocks away) and had many delicate objects. Comba also wanted to restart that collection’s educational outreach program for third graders, which had been suspended because of the move, as soon as possible. Interns assisted the staff with packing, wrapping and sealing boxes in the basement of Bridges; later the team hand-carried them up by elevator and then carefully loaded and unloaded them in and out of the museum van. Moving the Native American collection took about three months—and countless van rides—to complete.

Hudson made sure that interns knew the protocols of proper object handling, dispelling the myth that the only way to touch museum items is with white cotton gloves. “The cotton fibers of a white glove can snag loose ends of baskets. If you are handling anything fibrous, it could be a disaster,” she says. Nitrile gloves are typically used to handle photographs and prints (they leave no fingerprints), but experts don’t wear them when picking up smooth objects like vases (too slick). Overall, the growing professional consensus is that clean bare hands provide a better and more secure grip, especially when picking up organic items made of stone or bone, such as arrowheads.

Fraley, one of the interns, used her bare hands to check and pack 450 Chinese snuff bottles from the Qing Dynasty, one of her many special assignments. A history major, Fraley recalls getting into a rhythm as she handled the ornate bottles, which ranged in size from 2 to 4 inches. Using poly foam batting, Fraley gently wrapped and nestled the bottles into their drawer-like cubbies encased in pre-cut Ethafoam, a brand of foam often used for artifact storage. As she worked, Fraley examined the intricate details of these ancient mini works of art. “The artist used a fine paintbrush and painted the insides of the bottles,” she says. “It was so special to be able to handle and observe these up close.”

Some heavy or incredibly fragile items, such as Italian Renaissance panel paintings from the Kress Collection, were handled by professional fine art movers.

Comba lost track of how much poly foam was used to securely wrap objects. “It was everywhere,” he says of the material that is firm enough to cushion delicate objects but soft enough not to put unwanted pressure on certain structural elements, like the spout of a teakettle. “You want everything to have a soft landing at every step of the way,” he says.

Items were transported three ways. Heavy and incredibly fragile pieces—like the Kress Collection’s Italian Renaissance panel paintings, a 19th-century marble bust and a Sam Maloof walnut music stand—were given to a professional art-moving company that spent only two days on campus. Most objects, however, were moved using campus vans. Lightweight ones—such as photos, prints, scrolls and manuscripts—were walked over in rolling restaurant-style carts. “It was a huge responsibility, and it was nerve-racking,” Fraley says of those early-morning expeditions. “We just took our time, but I’ll tell you, that short walk never felt so long.”

Days after the last objects were moved to the Benton on March 3, 2020, the pandemic hit. Interns were sent home, which left staffers the final task of checking in and storing those remaining items in their new homes. “We didn’t have a time pressure to finish the job,” admits Comba. “You could call that a pandemic benefit.”

As far as Comba has seen, no item sustained any damage from the moving process, marking this move a huge success.

Now, months after the entire collection has officially settled into its new digs, the reverberations from the relocation still echo for those on the moving team, especially Fraley. “This really opened my eyes to the depth of the moving process and the specialness of this collection,” she says. “Because of this experience, I will never look at any museum the same way ever again.”

The long-awaited Benton Museum of Art at Pomona College opened to the public in May 2021 with reservation-based visits after the planned 2020 opening was delayed by the pandemic.

The long-awaited Benton Museum of Art at Pomona College opened to the public in May 2021 with reservation-based visits after the planned 2020 opening was delayed by the pandemic.

Named in recognition of a $15 million gift from Janet Inskeep Benton ’79, a longtime supporter of the arts and a member of the Pomona College Board of Trustees, the 33,000-square-foot museum provides not only space for the public enjoyment of art but also serves as a teaching museum and a new gathering spot on campus.

The public community celebration planned for November 13 will be preceded by an opening reception and artist talk with Sadie Barnette on November 6 as part of Sadie Barnette: Legacy & Legend. On November 11, the Benton will feature guest curator Karen Kice and graphic designer Amir Berbić as part of Sahara: Acts of Memory. Throughout the fall, the $44 million facility designed by Machado Silvetti Associates and Gensler will host events for the campus community in the museum’s courtyard and striking glass-walled interior spaces.

American Crossroads

As an inquisitive girl growing up in the city of Pomona, Genevieve Carpio ’05 learned about her world while riding around town with her family. The adults in her life were happy to converse with their captive passenger, especially one so unusually attentive for her age.

As an inquisitive girl growing up in the city of Pomona, Genevieve Carpio ’05 learned about her world while riding around town with her family. The adults in her life were happy to converse with their captive passenger, especially one so unusually attentive for her age.

With her grandfather behind the wheel of his Chevy pickup, the girl soaked up tales of Carpio family history as poor migrant farmworkers who fled the Mexican Revolution and soon settled in Pomona’s historic barrio. And while cruising Claremont with her mother in the family car, she got a glimpse of her academic future.

The college town was close to the North Pomona home of the Carpios, one of the first Latino families to buy property in a formerly red-lined neighborhood, once reserved by contract for whites. Their abode was now Claremont-adjacent, just a short drive north on Indian Hill Boulevard, which seemed like an artery to another life.

“For fun, my mom enjoyed driving around Claremont and looking at the houses and we would say, ‘Which house do you want to live in? Oh, I want to live in that house. No, I want to live in that house.’ And then she would take us around the colleges, just to look at them.”

But Grace Carpio, a stay-at-home mom who hails from Puerto Rico, was not just sightseeing. She was planting a seed. “That’s where you’re going to go to college when you grow up,” she would say with certainty.

“No, I’m not,” young Carpio would snap back. “I’m going far away.”

Time proved her mother right. And time also taught Carpio an important lesson about the meaning of success and the value of uncovering untold histories in her own backyard.

“For me, having grown up in a very working-class community, success always meant getting as far away as possible,” says Carpio, who did research in Brazil and Argentina as an undergraduate. “In anthropology, it seemed to me there was this idea that you go to these places very far away to study something new and translate it according to these anthropological frameworks. But it was really being in Brazil where I noticed that, as a person who wasn’t Brazilian, there was a lot I had left to learn about interpreting these cultures.”

During her South American stay, coincidentally, Carpio was reading a book exploring the history of race and labor in the citrus industry of Southern California written by historian Matt Garcia, who holds a doctorate from what is now Claremont Graduate University.

From her vantage point in the Southern Hemisphere, Carpio experienced a paradigm shift that would send her career in a new direction.

“It opened this window into being able to do work in the communities that you come from,” says Carpio, now an associate professor in UCLA’s César E. Chávez Department of Chicana/o and Central American Studies. “It showed me it was possible to be able to write about home in a way I had never considered before.”

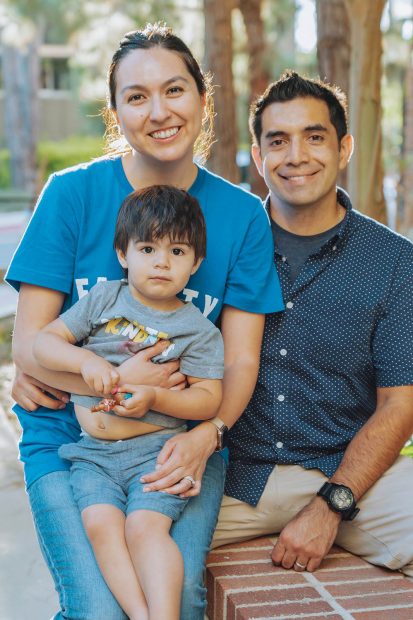

Genevieve Carpio ’05, husband Eric Gonzalez and son Elliot. Their daughter was born in September.

The past summer was an eventful one for Carpio and her family—husband Eric Gonzalez and their rambunctious 3-year-old boy Elliot. They moved into a new faculty apartment on the UCLA campus, making room for the arrival of their second child, Amelia, born on Labor Day.

If her schedule was harried, Carpio didn’t show it when she met for an interview in a shaded picnic area outside her office. At 38, she looks young enough to pass for one of her own graduate students. She’s relaxed and down-to-earth, yet also dignified. Despite sitting on a hard bench for an hour, Carpio barely shifts position, reflecting an inner discipline that was apparent to her parents from childhood.

Her rise through academia has been steady and strategically planned. She went straight up the academic ladder: B.A. in anthropology from Pomona (2005), M.A. in urban planning from UCLA (2007), doctorate in American studies and ethnicity from USC (2013), and finally a postdoctoral fellowship in ethnicity, race and migration at Yale (2015).

And on July 1, she earned tenure at UCLA, a status that brings professional privilege and private relief. She had dreaded the instability of the untenured, with the prospect of losing her job and being forced back on the “super mobile” college job market that could have landed her anywhere in the country.

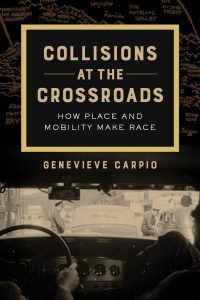

Carpio is certain that her tenure bid was boosted by the publication of her well-written and well-received book—Collisions at the Crossroads: How Place and Mobility Make Race (University of California Press, 2019).

Thus, ironically, her work on mobility helped ensure that she could stay put.

“I feel like I’m at this really exciting crossroads,” she says, using a term for intersection that figures prominently in her life and work.

UCLA courses taught by Prof. Genevieve Carpio include Race and the Digital Divide and Barrio Suburbanism.

In the book, Carpio’s first, she examines the history of the Inland Empire through the lens of mobility—the freedom of movement, granted or denied to various racial groups. She focuses on specific policies used to control not just mass immigration, but also the “everyday mobilities” of marginalized, non-white populations.

In the book, Carpio’s first, she examines the history of the Inland Empire through the lens of mobility—the freedom of movement, granted or denied to various racial groups. She focuses on specific policies used to control not just mass immigration, but also the “everyday mobilities” of marginalized, non-white populations.

Those policies included bicycle ordinances enforced disproportionately against Japanese workers; laws against joyriding that sent many Mexican youth to reform schools; the forced confinement of Native Americans at federal Indian boarding schools; and laundry laws aimed at driving single Chinese men out of downtown Riverside by banning them from washing their clothing outdoors.

Carpio’s book is part of the publisher’s American Crossroads series launched some 25 years ago, and it perfectly meets the original mission, says series co-founder George Sanchez, a USC professor of American studies, ethnicity and history, who served as Carpio’s doctoral dissertation advisor.

“We were going to go after books that made a difference in the field, that we thought were breaking new ground,” Sanchez explained during a presentation at UCLA’s Chicano Studies Resource Center shortly after the book’s publication. “Gena’s book fits this beautifully. … She shows things that were invisible to other scholars.”

Invisible, yes, but partly because other scholars weren’t looking. The Inland Empire is quasi-virgin territory for serious academic investigation, Carpio says. The academic neglect has the effect of silencing the voices of migrant workers and communities of color, overlooking the very people who helped build the citrus industry for which the Inland Empire is historically renowned. And by default, it allows this historical vacuum to be filled by the self-promoting origin myth of white settlers who colonized the area in the late 1800s—as if history began with them.

Riverside’s Washington Restaurant, established in 1910 and named for the first U.S. president, was operated by the Harada family, Japanese Americans who were later forcibly relocated during World War II. (Courtesy of the Museum of Riverside, Riverside, California and the Harada Family Archival Collection)

Carpio’s research began more than 10 years ago as part of her doctoral dissertation. At the time, it wasn’t history that drew her attention to modern conflicts over mobility. It was current affairs.

In the early 1990s, San Bernardino authorities had banned lowriders from a city festival celebrating the fabled Route 66, even though Chicano car culture had flourished on the thoroughfare which traversed the city’s historic Mt. Vernon barrio.

“It was so wrong,” Carpio says. “I really wanted to understand what it meant, and why it bothered me so much.”

“It was so wrong,” Carpio says. “I really wanted to understand what it meant, and why it bothered me so much.”

She was also incensed by the proliferation of sobriety checkpoints in heavily Latino neighborhoods. In the guise of public safety, the checkpoints worked as immigration traps for undocumented drivers, caught on their way to work or to drop their kids at soccer practice. This “hyper-policing” turned the streets into “minefields,” she says, and infused fear into everyday trips.

Carpio’s outrage led her to join protests organized in 2008 by the Pomona Habla Coalition. She and fellow demonstrators would stand at street corners with signs warning motorists of checkpoints ahead.

Such restrictions on mobility, she realized, “send powerful messages about who belongs and who doesn’t belong.”

Carpio showed an early commitment “to fostering authentic, non-hierarchical relationships between college and community,” says Pomona Prof. Gilda Ochoa, the advisor on Carpio’s senior thesis, White Hoods and Welcome Baskets: The Forming of a Mexican Barrio in Pomona 1920-1940. “Before there was the Draper Center (for Community Partnerships), Genevieve and I were on campus task forces together working to enhance community partnerships,” says Ochoa, a professor of Chicana/o-Latina/o studies. “I was lucky to learn from her. A few years after she graduated, she even recruited me to join her on the Historical Society of Pomona Valley.”

Carpio spent a decade of dogged digging through the dusty, musty files of such historical societies and other public history sources. She rummaged through library basements, scoured forgotten public records, explored local museums and perused private family photo collections. Moreover, she sought out those quirky, unheralded folks who make local history their life’s mission.

She refers to that disparate pool of primary sources as “the rebel archives,” a term coined by historian Kelly Lytle-Hernández, the bedrock for constructing a “subversive history” of the Inland Empire. She proudly points out the hefty 70-page notes section at the back of the book, where she documents the oft-neglected archival sources she unearthed.

“I wanted to create a bit of a trail so that those who were coming after me would have this place to start, would have this map of the various resources in the region.”

Vincent Carpio Sr. was a field laborer before joining the U.S. military. He urged his granddaughter to pursue an education.

Carpio likes to say she was raised in the borderlands, the area where eastern Los Angeles County, specifically Pomona and Claremont, meets the counties of San Bernardino and Riverside. From there, the path to success led due west to the big city, at least for ambitious students like her. Nobody thought of looking east to the vast open spaces of the Inland Empire, which she considered an intellectual wasteland at the time.

Two uncles on Carpio’s mother’s side, Osvaldo and Nonato Garcia, also served their country.

Once again, it took distance for her to grasp the importance of her own backyard as a fertile territory for academic study. During her postdoc at Yale, Carpio spent two years writing and thinking about issues back home. So there she was, ensconced behind Ivy League walls almost 3,000 miles away, in a program that required “direct engagement with the cultures, structures, and peoples” that were the subject of her studies.

And it dawned on her that this history was her story.

“It’s the story of my family.”

Genevieve Tañia Carpio is a fourth-generation American, a great-granddaughter of Mexican immigrants Frank and Margaret Carpio from San Francisco del Rincón, Guanajuato, who came to this country in 1916 at the height of the Mexican Revolution. Four years after their arrival, they welcomed their first U.S.-born son, Vincent Victor Carpio—Genevieve’s grandfather.

Little Vincent’s mother, who had married at 16, could not read or write, according to the 1930 census, which also identified his father as a “picker” working in the “citrus fruit” industry. By then, the family—including 10-year-old Vincent’s four adult siblings—lived on West 12th Street in the heart of the old Pomona barrio. During the ensuing Depression, the Carpio family would head north in their horse-drawn covered wagon to work the fertile fields around Fresno.

Vincent grew up in his father’s footsteps, dropping out after sixth grade to follow the migrant trail. His aborted schooling would later motivate him to stress the value of education for his son, Vincent Victor Carpio Jr., and his granddaughter, known as Gena, the girl who would listen to his family stories in the car.

Interestingly, official records underscore the theory that race is malleable: Vincent Sr. was identified as Mexican in the 1930 census, but 13 years later the U.S. Army drafted him as white. During his 17 months of service, Pvt. Carpio saw action on D-Day and at the Battle of the Bulge. He was seriously injured by an artillery blast, spent five months in a military hospital and was sent home with a Purple Heart and Bronze Star for bravery.

Back in Pomona, the veteran struggled to find work. He repeatedly tried to get a job with the city’s public works crew and was finally hired one day, only to find the job was “no longer available” when he reported in person. His name must have sounded Italian on the phone, his family reckons, but his appearance was unmistakably indigenously Mexican. Undeterred, the Carpio patriarch pushed his way onto the payroll, promising to work a week for free to prove himself. He wound up working for the City of Pomona for more than 20 years.

Carpio’s grandfather died on his 92nd birthday in 2012, living long enough to see his granddaughter fulfill the hopes for an education that had eluded him. She had been named Genevieve after one of his daughters who died as an infant during the war, while he was away at boot camp. For her senior thesis at Pomona in 2005, Carpio interviewed her grandfather, then in his 80s, for one of many oral histories that eventually helped shape her book.

“We really valued oral history because it reveals stories that aren’t in official documents,” she says. “They aren’t the dominant stories about powerful people, the mayors or the business owners, but about the folks who built the city. Nobody knows who digs up the streets, who paves the streets. But that’s what my grandpa did, you know, he dug up the streets in Pomona.”

Her father, Vincent Jr., a long-time Chicano community activist, also cultivated a love of culture and history in his daughter as a young teen, urging her to volunteer at the Ygnacio Palomares Adobe, a Pomona museum.

Although Carpio graduated from high school 20 years ago this past summer, her mother still gushes with pride that Gena was accepted to all 12 colleges where she had applied. Carpio almost passed on applying to Pomona because she thought it would be too hard to get in, and “I was just so scared of rejection.” She still becomes emotional thinking of the day her admission letter from Pomona arrived in the mail.

“I opened it up and my knees buckled. I fell to the floor, and I just started sobbing. I was so happy.”

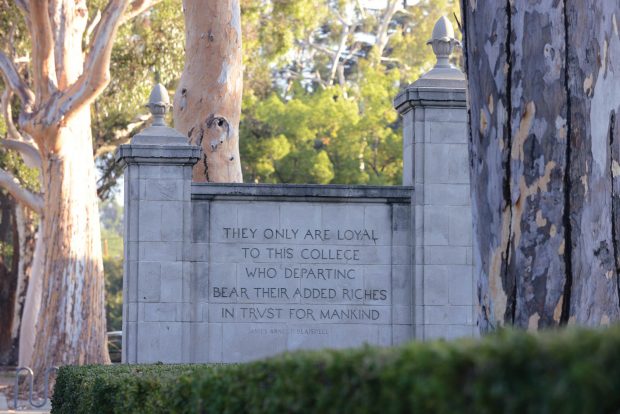

Four years later on her graduation day, Carpio joined her classmates in the traditional passage through the college gates with the weighty inscription: They only are loyal to this college who departing bear their added riches in trust for mankind.

Four years later on her graduation day, Carpio joined her classmates in the traditional passage through the college gates with the weighty inscription: They only are loyal to this college who departing bear their added riches in trust for mankind.

“The idea is that education is not just for your own enrichment, but for you to do something good with what you’ve learned,” she says.

‘“I hope this book encourages people to write their stories, especially those that so often have been left off the map.”

“I feel like I’m at this really exciting crossroads.”

–Genevieve Carpio ’05