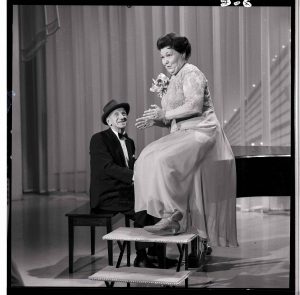

Mrs. Miller performs on TV’s The Hollywood Palace.

Hear for Yourself

If you’ve never heard Mrs. Miller, or even if you haven’t heard her lately, go to YouTube, and then get back to us …

FEW POP SONGS are as delicate, lovely and sophisticated as Antônio Carlos Jobim’s bossa nova classic, “The Girl from Ipanema.” Most know it from the version recorded by Stan Getz and João Gilberto with vocals by Gilberto’s wife, Astrud. She is neither a trained nor technically proficient singer, which lends the song its magic. Her soft, shy sibilance fits the song’s irresistible sway, the perfect marriage of dreamy soundscape and insouciant delivery. “And when she passes, each one she passes goes, ‘Ah!’”

This, then, is the setup for one of the greatest jokes in pop music history. Mrs. Miller’s trip to “Ipanema” is a master class in her art. The track opens with 34 seconds of what may be the lushest, most sweeping treatment the song has ever known.

And then at 0:35—to adapt a phrase from today’s electronic dance music scene—Mrs. Miller delivers the drop. “AhhhOHH, but I watch her so saaAAad-le-EE-ee….” If Astrud is the voice of the seductive Rio beauty, then Mrs. Miller is a rogue elephant stampeding down the beach, trumpeting away without a care in the world. It’s not that Mrs. Miller can’t sing; it’s how she can’t sing. She proclaims each syllable as grand opera—the kind that’s shouted above thunderous tympani—and her vibrato is seismic. Pitch is of no concern; that she often comes close, in fact, renders her delivery even more maddening. And she never met a downbeat she couldn’t miss.

If this sounds vicious, please know that a handful of music nuts—myself included—adore Mrs. Miller, and being objective isn’t easy, especially about an artist—an alumna of the College—whose notoriety came seemingly as the butt of an extremely cruel joke.

Because this issue of PCM is dedicated to humor, I felt I had to check to see if her music is still potent nearly 50 years on. Is the joke funny? Was it ever? An uninitiated friend was driving us to dinner. “Mind if I play something?” I asked, slipping in a CD. Thirty-four seconds of instrumental intro. My friend smiled and nodded. This is good! Then it happened. He started laughing so hard, he had to pull over. “Oh my god!” he said, gasping to contain himself. “What is she … ? MAKE IT STOP!”

Meet Mrs. Miller

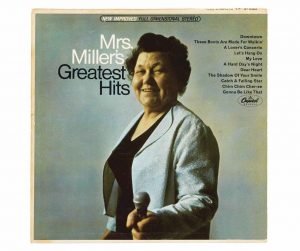

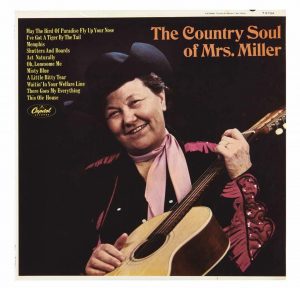

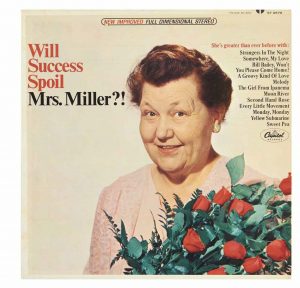

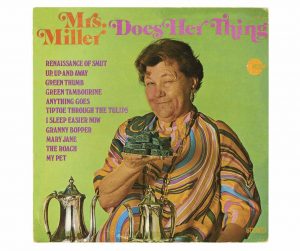

She had a first name. It was Elva. The fact that she didn’t use it professionally is a clue for understanding the joke and determining if Elva Ruby Connes Miller ’39 was in on it or not. More clues in unraveling the mystery: She released three albums—Mrs. Miller’s Greatest Hits, Will Success Spoil Mrs. Miller?, and The Country Soul of Mrs. Miller, covering everyone from the Beatles to Buck Owens—in under two years (1966–67) on entertainment industry behemoth Capitol Records. A fourth album, Mrs. Miller Does Her Thing, was released in 1968 on a tiny label out of Hollywood. That Mrs. Miller disowned this effort is the strongest evidence we have that she wasn’t fully in on but later caught on to what was happening. We’ll get to all of that soon enough, but first we have to meet Mrs. Miller.

She had a first name. It was Elva. The fact that she didn’t use it professionally is a clue for understanding the joke and determining if Elva Ruby Connes Miller ’39 was in on it or not. More clues in unraveling the mystery: She released three albums—Mrs. Miller’s Greatest Hits, Will Success Spoil Mrs. Miller?, and The Country Soul of Mrs. Miller, covering everyone from the Beatles to Buck Owens—in under two years (1966–67) on entertainment industry behemoth Capitol Records. A fourth album, Mrs. Miller Does Her Thing, was released in 1968 on a tiny label out of Hollywood. That Mrs. Miller disowned this effort is the strongest evidence we have that she wasn’t fully in on but later caught on to what was happening. We’ll get to all of that soon enough, but first we have to meet Mrs. Miller.

She was born and raised in mid-American cattle country, where she met and married John Richardson Miller, a man nearly 40 years her senior. They survived the Depression and retired to Claremont (as people do) in 1935. As a housewife with time on her hands, Elva studied music at Pomona, where, she told a Life magazine reporter, the students warmed up to a more mature classmate. “They liked the idea of an older woman there,” she said. “And within three weeks they were coming to my house, to copy my notes or listen to my records.”

And by records, she meant the ones she’d recorded. Mrs. Miller booked time at local studios (paid for by Mr. Miller) to indulge her love of singing. She told the Progress Bulletin, “[Making Greatest Hits] certainly wasn’t my idea. It was just a series of coincidences that could happen to anyone. Everyone has a hobby. Some people take pictures and file them in albums. Others paint pictures and store them in the garage. I’ve made records of sacred or classical songs for my own amusement. A closet at home is filled with them.”

Some of them found their way out of that closet: She would give records to churches and day care centers. Along the way she met three men who would steer her toward becoming a reluctant recording star. Gary Owens was a deejay at Los Angeles radio station KMPC who, following Mrs. Miller’s success, became a regular on ’60s TV comedy sketch show Laugh-In. He heard one of her records and sought her out to record comic jingles and station IDs. In his tongue-in-cheek Greatest Hits liner notes, Owens claimed to have discovered Mrs. Miller. That honor actually belonged to Fred Bock, a church musician whom Mr. and Mrs. Miller hired to accompany Elva on her hobby recordings. Bock, in turn, introduced the Millers to Lex de Azevedo, a novice record producer who had industry “connections” thanks to being the son of one of the King Sisters.

With that, the stage was set.

A Capitol Idea

So why would a leading record label—home to the Beatles and the Beach Boys, to Frank Sinatra’s imperial period and Peggy Lee’s renaissance—want to have anything to do with Mrs. Miller? Maybe because Jonathan and Darlene Edwards won a Grammy.

So why would a leading record label—home to the Beatles and the Beach Boys, to Frank Sinatra’s imperial period and Peggy Lee’s renaissance—want to have anything to do with Mrs. Miller? Maybe because Jonathan and Darlene Edwards won a Grammy.

Cocktail club singer Darlene Edwards sang sharp—distressingly so—and her pianist husband Jonathan had the unique ability to play different keys and separate time signatures simultaneously. As illustrated by the cover to their debut album (on Columbia, Capitol’s main rival), he was born freakishly with two right hands.

It was a funny joke perpetrated by jazz vocal great Jo Stafford and her big band–leader husband Paul Weston. Stafford was known to have stunningly perfect pitch; so sure was her instrument that she could sustain the Herculean feat of intentionally singing above pitch. And he was so nimble on the 88s that he could accompany in fitting style by throwing in extra beats per measure and flying off into impossibly inept cadenzas. They used these dubious talents to personify two ditzy, dreadful lounge lizards—Jonathan and Darlene Edwards—to entertain their friends at parties. The gag was so popular among jazzbo hipsters that Stafford and Weston released The Piano Artistry of Jonathan Edwards just for kicks.

Imagine their surprise when its follow-up brought home the 1961 Grammy for Best Comedy Album and revved up the market for musical comedy albums in general. With the industry’s need to give the people more of the same, record company halls soon resounded with, “Get me the next Jonathan and Darlene Edwards!” At Capitol, Mrs. Miller’s do-it-yourself 45s ended up in some talent screener’s inbox; by that time Bock had convinced her to record a couple of the day’s pop hits. The pitch was made: Rather than find someone talented to play dumb like Stafford—someone who would expect to be paid—why not go with someone actually untalented?

Mrs. Miller was signed. De Azevedo was tapped to produce. Bock helped with the arrangements and recording. Owens came on board to add industry cred. And this juicy bonus: Rumors persisted, once the album was a hit, that Mr. Miller had footed the bill for the whole enterprise, as he had done for all of his wife’s hobbies. (Confronted with this by the Progress Bulletin’s Vonne Robertson, Mrs. Miller reportedly snapped, “He didn’t buy me a career!”)

There was a significant and telling departure from the Edwards formula—a ready-for-pasture lounge act massacring yesterday’s moldy oldies much to the delight of the hipper-than-thou cool school. (Stafford and Weston enjoyed a stupendously long career and would eventually have the Edwards record hits of the day as well, including the Bee Gees’ falsetto-driven disco smash “Stayin’ Alive” in a parody so wicked and on-the-nose that Barry Gibb allegedly was not amused.)

Capitol’s grand plan for Mrs. Miller drew inspiration from the nascent Silent Majority v. Hippie Freak culture wars. The joke was funny because she was someone on the wrong side of cultural history, proving how far behind Mom and Pop had been left by the rock ’n’ roll revolution. Not that she would be brought in on the joke; that might ruin its purity. They told her she would be presenting rock ’n’ roll as opera.

What follows is Mrs. Miller’s recounting of how Greatest Hits was made, assembled from several chronological news sources spanning a two-year period, a period where what had happened to her slowly dawned on Mrs. Miller: “[Recording] it was easy. We didn’t even have rehearsals. If there ever was a square, I’m it. I’d never attempted popular songs [before]. The studio men just popped the music in my hands—sorta sneaky like—and I started. I don’t sing off-key and I don’t sing off-rhythm. They got me to do so by waiting until I was tired and then making the record. Or they would cut the record before I could become familiar with the song. [I suspected something was up] when they printed [my worst performance of] ‘The Shadow of Your Smile.’ They told me it was an experiment. I am naïve, and I am somewhat lacking in musicianship, but I really [didn’t think it was] a gag. At first I didn’t understand what was going on. But later I did, and I resented it.

“I don’t like to be used.”

The Hits Just Keep on Coming

Capitol released Mrs. Miller’s cover of Petula Clark’s “Downtown” as a single along with the album. What happened next was well captured by Joe Cappo writing in the April 21 Chicago Daily News: “Wally Phillips, WGN’s zany morning disk jockey, premiered the LP on air last Friday. [He reports] the first batch of people who called said, ‘Get that nut off the air.’ Then after a few more plays, the listeners said, ‘We want more Mrs. Miller. She’s better than the rest of the junk you play.’ Phillips says he has received hundreds of telephone calls since the first playing and is scheduling at least one Mrs. Miller tune every day. Phillips said, ‘I play her records when I want to work off my hostilities against the world.’”

Greatest Hits sold out of its initial run of 50,000 in a matter of days. Another 150,000 were quickly pressed. They sold in a matter of weeks. Reports vary on how many finally were sold, ranging from 250,000 to 600,000.

Mrs. Miller Mania had hit. This was her itinerary for 1966–68: She was whisked to New York to be on the Ed Sullivan Show. She would also be a guest of Merv Griffin, Mike Douglas and Art Linkletter. There was The Joey Bishop Show. There was an appearance on TV’s Hollywood Palace where she sat atop a piano to sing “Inka Dinka Doo” with Jimmy Durante. There was an appearance at Carnegie Hall with Red Skelton. Hollywood came calling. She played a version of herself in a low-budget film called The Cool Ones with Roddy McDowell.

Mrs. Miller Mania had hit. This was her itinerary for 1966–68: She was whisked to New York to be on the Ed Sullivan Show. She would also be a guest of Merv Griffin, Mike Douglas and Art Linkletter. There was The Joey Bishop Show. There was an appearance on TV’s Hollywood Palace where she sat atop a piano to sing “Inka Dinka Doo” with Jimmy Durante. There was an appearance at Carnegie Hall with Red Skelton. Hollywood came calling. She played a version of herself in a low-budget film called The Cool Ones with Roddy McDowell.

A nightclub act was quickly pulled together with a backing band and chorus. (An ad in the trades may or may not have read, “Wanted: musicians who can keep a straight face.”) Mrs. Miller’s first appearance was in Ontario at the Royal Tahitian. (A review had positive things to say … about the “good chicken stuffed with almonds and apples.”) Two more albums were made, each selling significantly fewer copies than the previous. A fourth appeared on a small independent label, Amaret Records. It disappeared without a trace, despite a promotional appearance with Johnny Carson on The Tonight Show.

And then it was over.

Reports also vary on profits. Capitol is said to have made millions off of the Mrs. Miller phenomenon. She is reported to have earned less than $40,000 from Greatest Hits and not more than $100,000 in total earnings from royalties, fees and personal appearances.

The May 13, 1966, issue of Time magazine mentioned in what amounted to a parenthetical aside that Mrs. Miller had put her earnings into a medical-care trust fund. Likely over the course of Mrs. Miller Mania and certainly by its end, Mr. Miller had needed round-the-clock nursing care. He died at age 96 in December 1968.

I Don’t Get It

How do you explain Mrs. Miller Mania? She was interviewed by The Collegian after her initial success and said, “I just don’t know what to think about it, because I have never done anything which has brought any attention of any kind whatsoever, and I just don’t know what to say. Now the boys in Vietnam, they want me to come, but I have to go back East first. I will go there because I think the service boys come first.” On further reflection, she told reporter Bob Thomas, “I don’t understand [my record sales], but teenagers seem to be buying them. As I see it, there are two kinds of teenagers. There are the sophisticated ones, who dress like Sonny and Cher. They don’t buy my album. Then there are the teenagers who dress neatly; they are the ones who do buy my records.”

How do you explain Mrs. Miller Mania? She was interviewed by The Collegian after her initial success and said, “I just don’t know what to think about it, because I have never done anything which has brought any attention of any kind whatsoever, and I just don’t know what to say. Now the boys in Vietnam, they want me to come, but I have to go back East first. I will go there because I think the service boys come first.” On further reflection, she told reporter Bob Thomas, “I don’t understand [my record sales], but teenagers seem to be buying them. As I see it, there are two kinds of teenagers. There are the sophisticated ones, who dress like Sonny and Cher. They don’t buy my album. Then there are the teenagers who dress neatly; they are the ones who do buy my records.”

This points to the 1960s culture wars, but in her admitted naïveté, Mrs. Miller overlooked something crucial. Like the boys in Vietnam or the hippies in their freaky frippery, her “character” embodies a sign of the times. As she warbles opera in her fusty frock and Sunday hat, she is the priggish society matron, the antithesis of all things with-it and groovy, practically begging for our smug derision. Think Margaret Drysdale on The Beverly Hillbillies, Mrs. Stephens on Bewitched, or, more benignly, even dear Aunt Bee and neighbor Clara on The Andy Griffith Show. Humor in those shows was often generated by letting the air out of such old gas bags. She’s singing rock ’n’ roll! But she can’t! It’s hilarious!

Recall as well that during Mrs. Miller Mania, America had its love affair with camp. We watched Batman on TV and listened to Tiny Tim (a hippie with talent who nevertheless warbled the hoariest of musical chestnuts while coyly strumming a ukulele). Even the Beatles got into the act with the likes of “When I’m 64” and “Yellow Submarine.” (Mrs. Miller took a ride on the latter.)

Capitol Records—home to polar opposites like “A Hard Day’s Night” and “Dear Heart,” both songs scaled by Mrs. Miller—had its fingers on that pulse. Ultimately, Mrs. Miller wised up as well. In a review of her February 1967 appearance at L.A.’s Cocoanut Grove nightclub, John L. Scott noted that Mrs. Miller was playing the show as pure comedy, noting that she delivered very deliberate one-liners with great comic timing. And she was very aware that she had the audience in stitches. She knows—’cause when she passes, each one she passes goes, “Ha!”

But that didn’t mean she gave in or pretended to be anything she wasn’t. She went by “Mrs. Miller” for a reason, and it wasn’t because it had a marketing ring to it. It was polite that wives were properly identified in public as their husband’s property. Interviewed by Skip Heller in an article in Cool and Strange Music Magazine, Mrs. Fred Bock—to sustain a trope—recalled when, after a gig, she, her husband and Mrs. Miller met actress Natalie Schafer (Mrs. Thurston Howell III, the Gilligan’s Island version of the blue-blooded old biddy). The actress said to Mrs. Miller, “You can call me Natalie.” To which Mrs. Miller replied, “And you can call me Mrs. Miller.”

Desafinado

Antônio Carlos Jobim, who gave us “The Girl from Ipanema,” penned another classic, “Desafinado” (translation: slightly out of tune). Its English lyrics speak of love gone sour; the original Portuguese gets at something deeper, suggesting that only privileged ears can hear things perfectly, that bossa nova can’t help but be out of tune. It chides, “What you don’t know and cannot feel is that those out of tune also have a heart.”

Mrs. Miller wasn’t the first pop sensation to have been lauded for singing poorly. In her day she was compared to the Cherry Sisters, a 19th-century vaudeville act popular although—no, probably because—it was said “they couldn’t speak, sing or act. They were simply awful.” And then there was Florence Foster Jenkins, the grossly untalented opera singer who rented grand opera halls to torture her friends. (In a 2016 film, Jenkins was played by no less than Meryl Streep, who proclaims, “People may say I couldn’t sing, but no one can ever say I didn’t sing.”) Susan Alexander Kane’s atrocious public screeching is a central plot point of Citizen Kane. And try as you might, you cannot forget William Hung, can you?

Music is a particularly prickly muse. We are very quick to accept, even champion, foibles and faux pas in other art forms. We celebrate primitive painters. We keep Norman Mailer in the pantheon despite his having opened Harlot’s Ghost with an egregious dangling participle. And Nicolas Cage keeps getting acting gigs, for crying out loud. But stray one iota off key….

It’s often said visionaries are ahead of their time. In 2019 we have a word for the Mrs. Millers of the world—disrupters—and it’s the hot thing to be. So isn’t it odd that the chaotic disrupter of the music industry’s professional norms and expectations—the joyous elephant stampeding down that Ipanema beach—was none other than the persona of the stuffy establishment matron whose comeuppance we so deeply desired? And if you’re having trouble wrapping your head around that double irony, here’s the mindblower. When it comes to cooler-than-thou, competence isn’t spared, either.

Nearly concurrently, 30 miles to the southwest, another transplant from the East who blossomed in a college music department was about to become a thousand times more famous than Mrs. Miller and come crashing down a hundred times harder. Only she was the best voice of her generation. Karen Carpenter came out of Downey, Calif., and the music department of California State University, Long Beach, to sell more than 90 million records. Carpenters records dramatically changed popular music—yes, even rock ’n’ roll. The duo invented the guitar-driven power ballad, and their recording, performing and marketing techniques set standards throughout the industry. But they could not break the critical determination that they were unhip and square—okay, they were unhip and square—and that disservice lingers. Riots likely will break out should they ever be inducted into Cleveland’s Rock ’n’ Roll Hall of Fame.

Karen now is regarded as a preeminent interpretive pop singer, yet frustrations with the duo’s inability to shake their negative image, coupled with her own personal demons, led her to die of anorexia at age 32. Elva couldn’t sing a good note. Karen couldn’t sing a bad one. And both were out of tune with their times. Which just goes to show you that the arbiters of taste in their indifferent and often unfounded dismissals can be truly heartless monsters.

One for the Boys

Mrs. Miller and Jimmy Durante sing a duet on TV’s The Hollywood Palace.

Two postscripts. One bitten, twice shy? Hardly. It seems Mrs. Miller could not catch a break. After she was dropped by Capitol, news articles appeared noting that she was going to change her image. In April of 1968, she released Mrs. Miller Does Her Own Thing, working with noted L.A. producer Mike Curb. (He would go on to produce the Osmonds, date Karen Carpenter and serve as California’s lieutenant governor.) Scattered among the usual pop hits that anyone but her should be singing, were suggestive, trippy titles such as “The Roach,” “Mary Jane,” “Granny Bopper” and “Renaissance of Smut,” that would have been better if the pot and porno references had at least been dressed up with coy double entendre. The cover was psychedelic and garish. Mrs. Miller is winking knowingly and offering a salver of brownies presumably enhanced with what we now call “edibles.”

Her new image was a pusher? Yet again, she had been hornswoggled. She didn’t get the sex and drug references. The cover art had been manipulated. She didn’t even get it when a winking Johnny Carson asked how the weeds were in her garden. (Was there ever a time when male entertainment honchos didn’t exploit their power differential with women? MAKE IT STOP!)

When she was woke to this new betrayal, Mrs. Miller said “Enough!” She lived quietly in Claremont but remained engaged in her community. She was the grand marshal for the Fourth of July parade, and she judged The Claremont Colleges’ Spring Sing. She moved to Hollywood, where she enjoyed classical concerts and theatre. She later moved to an apartment in Northridge that was destroyed in the 1994 quake. She was relocated to an elder-care facility, where she died in 1997. She was 90.

She did keep her promise to the boys in Nam. In 1967 she joined Bob Hope’s annual USO tour. Life magazine’s Jordan Bonfante covered it, noting of her performance, “In Vietnam, clad in jungle boots and a muumuu, she chatted with audiences about the 15 years she spent studying music, lopped five years off at each burst of laughter, and finally offered, ‘Would you believe one?’ When that was howled down, she confessed she was starting lessons ‘tomorrow.’”

She had timing. She had one-liners. And—as captured in photos of her among the adoring troops—she had the time of her life.

“And when she passes, each one she passes goes, ‘Ah!’”