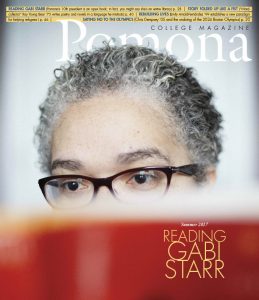

IN THE WEEKS before she is to leave New York City and move across the country, scholar and future college president G. Gabrielle Starr really should be shedding books and clearing shelves. Instead, a steady flow of new material keeps arriving, at her request and much to her delight.

Starr is reading ahead, poring over Pomona’s history, taking in all she can about the College’s past and present. This makes sense: Gabi was the kind of kid who made up homework for herself if she didn’t have any, just to have the chance to use her encyclopedia. By the age of 3, she was reading the newspaper headlines aloud from her father’s lap, and her mom recalls that “she always had a book—everywhere she went.”

From those early days, she never let go of the tomes.

Louisa May Alcott gave way to Immanuel Kant; Pride and Prejudice and Cane replaced Little House on the Prairie. As a professor of 18th-century English literature whose interests widened to incorporate neuroscience, Starr was soon writing the books, and her reading extended to fMRI brain scans as she found new methods to pursue her work in aesthetics. She also knew how to read people and the complex situations that come with leadership: Still pursuing intensive research, Starr became a savvy and much-loved administrator at New York University, rising to become dean of the College of Arts and Science, with some 7,000 students in her division.

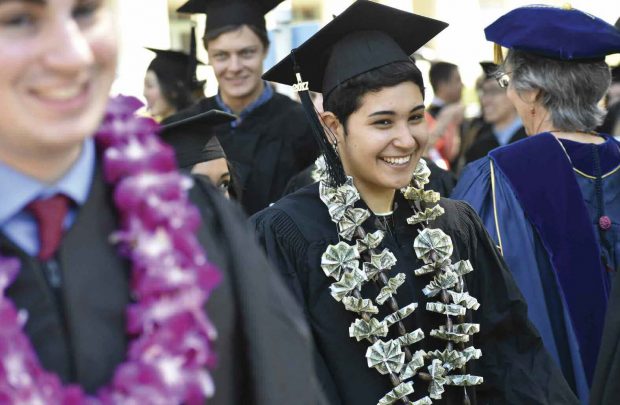

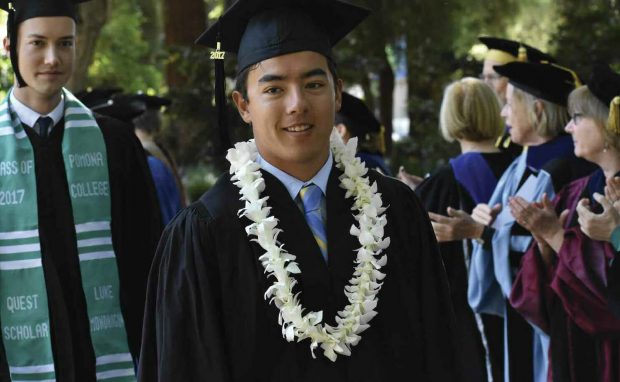

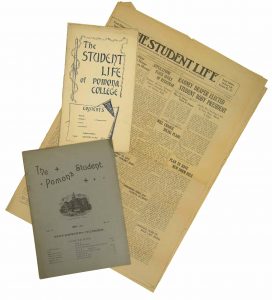

Today, The History of Pomona College, 1887–1969 is at the top of her reading list as she prepares to take office as the College’s 10th president in July, with her formal inauguration in the fall. “I’m not a fan of pomp and circumstance,” says Starr. “I want to start off my time at Pomona with immersion. What brings people to Claremont is that magic of a place” where the life of the mind thrives.

A Life in Books

We Sagehens are a proudly bookish bunch, so what better way to get to know our next president than through the authors and books that have influenced her most?

Read More

And yet there is an unmistakable sense of excitement at Pomona about her arrival. In her campus meetings, Starr clearly connected with her audiences, both intellectually and in a personal sense. Just as telling is the reaction at NYU, where colleagues seem to be undergoing the five stages of grief.

“She is ferociously brilliant. Absolutely brilliant,” says Professor Ernest Gilman, an English Department colleague and friend who has known her since she arrived at NYU in 2000. “There are a lot of smart people around here, and she stands out as an intellectual force.”

“There’s nobody who doesn’t like Gabi,” adds Gilman, noting that Starr “knows how to get things done without rattling anyone’s cage.”

Pamela Newkirk, NYU’s director of undergraduate journalism, puts it this way:

“I mean, no one’s smarter than Gabi. You can be as smart, maybe,” she says, laughing. “But beyond that, she’s also very warm, just on top of everything. I imagine she doesn’t sleep much because she seems to be everywhere. …

“I don’t know anyone who doesn’t adore Gabi. I just don’t. There probably is somewhere. I’ve never met that person. And that is not an easy thing at a place like this. This is a huge university. … And she’s also someone who I knew would be president of a college.”

STARR HAD ALREADY skipped kindergarten and the eighth grade and was still three years shy of adulthood when she got her hands on a copy of the Emory University course catalog, poring over the lists of classes. She remembers the cover was a watercolor scene of autumn trees on the campus and the theme was “A Community of Scholars.”

“It just seemed really magical,” she recalls. “And it was.”

Yes, Starr would set off for college at the age of 15, after some negotiations with her folks, who certainly knew the value of an education. Her mother, Barbara Starr, taught English and American history at Lincoln High in Tallahassee, Fla., the school Gabi attended. A sharp card player to this day, she negotiated for the teacher’s union. Gabi’s father, G. Daviss Starr, would earn his college degree at the age of 40 and eventually go on to become a professor at Florida A&M. An eloquent speaker with a penchant for Southern witticisms, he had a particular interest in the psychology of literacy. Her older brother, George, had already blazed the trail when, as a math whiz, he took off for college at 15, too.

Learning was at the core of life in their home just outside Tallahassee. Her grandmother (on her father’s side) also lived with them for much of Gabi’s childhood, telling family stories that reached back to the Jim Crow South, Reconstruction and the years before emancipation. The tales ranged from the humorous to the poignant and painful, but they were linked by an enduring faith, a shared commitment to human dignity and a belief in education through the generations. Always precocious, Starr not only took in the history but was eager to share what she learned. Knowledge didn’t mean much outside of a human web that would shape and refine it. “She was a born teacher,” says her mom. “When she would go to Sunday school, she would come back and teach her grandmother the Sunday school lessons.”

Still, as she reached her teens, her dad did worry about Gabi heading off to college so young, and wanted her to consider a women’s college. A deal was struck: She could go as far away as Atlanta’s Emory University, a roughly five-hour drive from their home.

“She was always adventurous,” says her mom. “She didn’t stop until she tried it. And you couldn’t stop her.”

At Emory, Starr plunged right into campus life. She started off studying chemistry, with plans to become a doctor and also to study music. There was so much to explore at the university: She even did a stint on the women’s club rugby team.

“I kind of felt like I was really thirsty and I got a drink,” she recalls. “Or maybe it really was like being in a candy shop—going to college—so many different possibilities to study things and learn about things that I never even conceived of.”

Soon enough the then-emerging field of women’s studies drew her in, as she became fascinated with who holds power in society and who doesn’t, and that discipline would be the source of her B.A. and M.A at Emory. She also spent a year at St. Andrew’s University in Scotland, studying philosophy of language, Arabic and French while becoming enamored with French classicism. “I’m a bit of an intellectual magpie,” she says.

Starr, though, would soon find an enduring intellectual focus, one that would guide the rest of her career.

IN HER ELONGATED NYU office overlooking Washington Square Park, Starr pulls one of her most beloved volumes from the shelf filled with books she has saved from her college days. It’s a copy of Kant’s Critique of Judgement, stuffed with more notes than a street preacher’s Bible. She kept it from a course on the book taught by French philosopher Jean-François Lyotard during her senior year at Emory.

That class opened her to the world of aesthetics and beauty and the sublime, a realm she has never really left. “I had never even heard of the sublime. I had no idea what it was. It was a fascinating course that really sparked an interest for me in how imagination works, and how human beings engage with all of the things that we create, and those ideas so big that we could never hope to make them real,” Starr says.

Exploring aesthetics was a natural path. Gabi’s father, who died in 2014, had always had a taste for collecting fine things: decorative arts and porcelain from China, as well as family documents and expansive books. Gabi herself had tapped into the arts at a young age, taking up piano at the age of 2, and she has always loved music. These things planted the seeds for her intellectual curiosity.

“We spend so much of our time adjusting the world to make it pleasurable and comfortable, but also challenging—in a positive way—interesting, engaging; and that’s everything from how we design the spaces we live in to how we groom the natural world. … It really speaks, I think, to a deep need that the world fit us in some way, as well as that we fit into the world—and I want to understand more about that.”

Off to Harvard for her Ph.D., she started to explore 18th-century ideas of the imagination. “Part of the great thing about this period in British life,” she notes, “is that it’s before the emergence of the modern disciplines, so if you were writing about what we think of as aesthetics, you’d be writing about it from the perspective of psychology, culture, economics, philosophy, physiology, literary history, any of those perspectives—and they all were combined into new forms of writing.

“So my intellectual history from that perspective has really been that the disciplines provide particular tools, but they don’t necessarily exist in isolation from one another.”

Starr soon made her own leap across the traditional disciplines.

With her Ph.D. in English and American literature from Harvard, Starr went on to a postdoctoral fellowship at Caltech and the nearby Huntington Library at a time when cognitive neuroscience was beginning to take off. She joined a reading group on the topic and took a course on fMRI. Delving into that new science, she began to look at imagination and the effects of the arts from the perspective of that field. Not long after she arrived at NYU, a New Directions fellowship from the Mellon Foundation allowed her to study neuroscience in greater depth.

IN NYU’S BRAIN imaging lab, Starr and her colleagues, it could be said, are getting inside the mind, to get a different read on the sublime. Their work involves looking closely at brain scans taken as subjects view art or listen to music from within an fMRI tube.

While people typically agree on what qualifies as a beautiful face or natural landscape, Starr notes, they typically disagree on the beauty of paintings, music, poetry—art. And when we are deeply moved by art, what goes on in our brains is quite a surprise. As she noted in one of her talks a few years back: “The pleasure that we get from the arts is about being able to take pleasure in unexpected places.”

Starr and her co-researchers have found that when people respond in the most positive way to a work of art, it activates what is known as the default mode network. These are the regions of the brain that work together when we are in a resting state—self-reflection, mind-wandering, remembering, imagination—and then they decrease in activity, for the most part, when we perform external tasks.

The fact that this network connected to our inner lives lights up when we have a deep response to art reveals an unexpected pathway between our interior and exterior worlds. Are there more such moments to be discovered? In one co-authored paper, Starr and her colleagues raise the possibility of “significant moments when our brains detect a certain ‘harmony’ between the external world and our internal representation of the self—allowing the two systems to co-activate, interact, influence and reshape each other.”

“Doubly directed” is the term Starr uses for it, and this could also be used to describe Starr. “I still like good, old-fashioned reading poetry and close reading of literature,” she says. “But this is a different kind of knowledge that’s also useful. I would never say that one would replace the other.”

Recognition and grant support have followed the research: Her most recent book, Feeling Beauty: The Neuroscience of Aesthetic Experience, was a finalist for the Phi Beta Kappa Society’s Christian Gauss Award. Starr was named a Guggenheim Fellow in 2015, and her work also has been supported by a National Science Foundation grant. Her novel research also draws speaking invitations, and she once deftly debated noted UC Berkeley philosopher Alva Noe on whether neuroscience can help us understand art. (You can find the video on YouTube.)

Starr’s approach is “something that very few of us can imagine or even fewer of us do, to make that kind of connection between the humanities and the cognitive sciences,” says Gilman, her NYU English colleague.

“Most of us are comfortably in our little groove; if your subject happens to be, you know, Spenser, you spend a lifetime studying Spenser; you don’t know much about anything else. She’s quite eclectic and broad in her passions.”

IT TAKES ONLY a quick scan of Starr’s NYU office to see the breadth of her interests. Her tomes range from Parental Incarceration and the Family to A Million Years of Music, and from The Works: Anatomy of a City to The Cambridge History of Literary Criticism. Books not only fill the shelves, they are also neatly stacked, five or six high, in a row down the middle of her conference table.

Her desk is covered in papers: “What’s active is what’s closest to the top,” she explains of her archaeological system, and there’s barely room for her side-by-side computer screens. Of course, her office is simply a reflection of her whirlwind academic life. Out of all these different things, what energizes her?

“All of it. All of it. I finally got two computer screens last year, and if I had three, I’d feel like it was just about enough information.”

Starr’s mind is running plenty of RAM as well. As dean, her days are full of meetings, events, decisions—but she still pursues her research and writes a steady flow of papers, turning in four this past school year alone. “The funny thing about the past six years is that since I became dean, I’ve become much more productive as a scholar … because the amount of time was so radically constricted,” she says. “It was: ‘do it in four hours every Friday afternoon or it’s never going to get done.’”

“I have come to really enjoy not stopping,” she says, laughing. “It catches up with you every now and then, but there’s a lot of fun to be had in helping students and figuring out big problems. And then going back and doing writing is relaxing. So I feel like there’s a balance. Also, I like to go and do things where they’re needed because that always feels good.”

STARR’S MOVE INTO leadership roles began after she earned tenure at NYU and was being recruited by another school: As a condition of staying, she asked to become director of undergraduate studies. “I wanted to be at a place where I could do things for my students and do things for my department because I’d been given this great gift of pretty much a job for life.”

Then colleagues asked her to run for chair of the English Department, which she accepted. Only a year later, when NYU Dean Matthew Santirocco announced his assumption of a new leadership role in 2011, he approached her to ask if she would serve as acting dean. Starr agreed, her work was well-received, and she wound up landing the permanent position in 2013, leading a division with a $130 million budget, a significant fundraising need and a high profile in the heart of Manhattan.

Then colleagues asked her to run for chair of the English Department, which she accepted. Only a year later, when NYU Dean Matthew Santirocco announced his assumption of a new leadership role in 2011, he approached her to ask if she would serve as acting dean. Starr agreed, her work was well-received, and she wound up landing the permanent position in 2013, leading a division with a $130 million budget, a significant fundraising need and a high profile in the heart of Manhattan.

NYU colleagues point to her oratorical skills as helping fuel her rise in the ranks there, with Professor Gilman noting a talk years ago at freshman orientation: “She just gave this amazing, passionate, brilliant speech,” he recalls. “I think some of the people who hadn’t known her began to take her more seriously.”

As dean, she partnered with New York City’s largest community college to create a pipeline in STEM education and helped launch a faculty partnership focused on the global humanities. She is particularly proud of her role in co-founding a cross-university prison education program offering A.A. degrees in the liberal arts to students in a medium-security prison in New York State. “It’s been a lot of fun to get to do things you can’t do when focusing primarily on scholarship and teaching,” she says, noting the opportunity to work with other institutions and even other parts of NYU. “It’s very satisfying when good things happen, when students who never would have come here come here graduate and are successful. That makes me happy.”

THAT’S RIGHT: HAPPY. Starr not only has a penchant for telling jokes; she can also slip quickly into pop-culture talk, discussing anything from The Simpsons to Ghostbusters to the old-school hip-hop of Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five. Her sense of joy is, to be honest, unusual in a college administrator, notes her NYU colleague Newkirk: “She’s a real person. She’s someone you would want to hang out with and have a drink and laugh with.”

Still, Starr says she is only a “sometimes” extrovert, and she never completely let go of the solitary girl who spent a lot of time out in the yard in a tree reading a book. (Once a year, she decompresses by rereading J.R.R. Tolkien’s entire Lord of the Rings trilogy.) “Because I liked imaginary worlds … I loved being inside them. And being an English professor is a great extension of that because then you get to bring other people inside of an imaginary world with you.”

Starr now awaits her move to the cloistered world of Pomona, with its own sort of magic. At NYU, embedded in the bustle of Manhattan, so much could pass by unnoticed. In Claremont, she sees herself popping into the dining halls, stopping by the gym to watch basketball games and, eventually, teaching a first-year seminar and carrying on research with faculty at Pomona and perhaps elsewhere in SoCal. “Pomona,” she says, “isn’t a world to itself or for itself. It is a place where we convene to imagine, argue, engage and build, together, many possible worlds. We can only do this as who we are—a community of the curious—and I’m eager to be a part!”

But first come the good-byes and thank-yous, and the matter of packing her books, shelf after shelf. Could there be any doubt? She is bringing all those beloved tomes, all those worlds, with her.

—Photos by Drew Reynolds

Starting at about 1 a.m. on June 5, Renwick House took a quick trip to its new home on the opposite side of College Avenue, making room for the construction of the new Pomona College Museum of Art. Renwick, which was built in 1900, is now the third stately home on College to have been moved from its original location, joining Sumner House and Seaver House, both of which were moved to Claremont from Pomona. The three-hour Renwick move, however, pales in comparison to the difficulty of the other two. The Sumner move took six weeks in 1901, using rollers drawn by horses. The 10-mile Seaver move, in 1979, took 20 hours.

Starting at about 1 a.m. on June 5, Renwick House took a quick trip to its new home on the opposite side of College Avenue, making room for the construction of the new Pomona College Museum of Art. Renwick, which was built in 1900, is now the third stately home on College to have been moved from its original location, joining Sumner House and Seaver House, both of which were moved to Claremont from Pomona. The three-hour Renwick move, however, pales in comparison to the difficulty of the other two. The Sumner move took six weeks in 1901, using rollers drawn by horses. The 10-mile Seaver move, in 1979, took 20 hours.

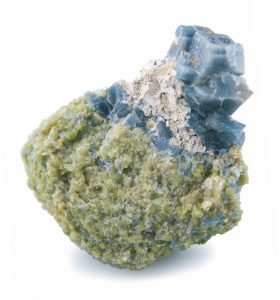

Deep in the bowels of the Geology Department in Edmunds Hall is a room full of storage cabinets with wide, shallow drawers filled with mineral specimens collected by Pomona geologists over the years. Many of them, according to Associate Professor of Geology Jade Star Lackey, go all the way back to the department’s founder, Alfred O. “Woody” Woodford 1913, who joined the chemistry faculty in 1915, launched the geology program in 1922 and served as its head for many years before retiring some 40 years later. Many of Woodford’s carefully labeled specimens came from the Crestmore cement quarries near Riverside, Calif. “Woody even had a mineral named after him for a while,” Lackey says, but the mineral was later found to have already been discovered and named. “More than 100 different minerals were discovered at Crestmore, including some striking blue-colored calcites—echoes of Pomona.” Ultimately, Lackey adds, Crestmore was quarried to make the cement to construct the roads and buildings of Los Angeles, but in the meantime, “Woodford trained many a student there, and the mineral legacy of Crestmore is widely known.”

Deep in the bowels of the Geology Department in Edmunds Hall is a room full of storage cabinets with wide, shallow drawers filled with mineral specimens collected by Pomona geologists over the years. Many of them, according to Associate Professor of Geology Jade Star Lackey, go all the way back to the department’s founder, Alfred O. “Woody” Woodford 1913, who joined the chemistry faculty in 1915, launched the geology program in 1922 and served as its head for many years before retiring some 40 years later. Many of Woodford’s carefully labeled specimens came from the Crestmore cement quarries near Riverside, Calif. “Woody even had a mineral named after him for a while,” Lackey says, but the mineral was later found to have already been discovered and named. “More than 100 different minerals were discovered at Crestmore, including some striking blue-colored calcites—echoes of Pomona.” Ultimately, Lackey adds, Crestmore was quarried to make the cement to construct the roads and buildings of Los Angeles, but in the meantime, “Woodford trained many a student there, and the mineral legacy of Crestmore is widely known.”

U.S. SEN. BRIAN SCHATZ ’94

U.S. SEN. BRIAN SCHATZ ’94

Then colleagues asked her to run for chair of the English Department, which she accepted. Only a year later, when NYU Dean Matthew Santirocco announced his assumption of a new leadership role in 2011, he approached her to ask if she would serve as acting dean. Starr agreed, her work was well-received, and she wound up landing the permanent position in 2013, leading a division with a $130 million budget, a significant fundraising need and a high profile in the heart of Manhattan.

Then colleagues asked her to run for chair of the English Department, which she accepted. Only a year later, when NYU Dean Matthew Santirocco announced his assumption of a new leadership role in 2011, he approached her to ask if she would serve as acting dean. Starr agreed, her work was well-received, and she wound up landing the permanent position in 2013, leading a division with a $130 million budget, a significant fundraising need and a high profile in the heart of Manhattan.