For Vidusshi Hingad ’25, the idea of being the first in her family to leave India for college abroad was nothing short of exhilarating—and daunting. But Pomona has proven to be a home away from home for the Mumbai native.

Vidusshi Hingad ’25

“From the moment that I landed in LAX, I have been exposed to a world of growth, inclusivity and, most importantly, genuine community,” says Hingad, who has participated in the mock trial program and served on the Associated Students of Pomona College’s Senate. “I have come to know that at Pomona, people are everything,” she says.

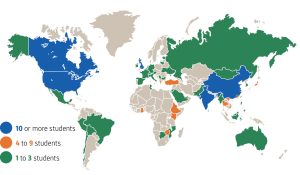

At the beginning of this century, international students were a modest presence at Pomona College, making up only about 2% of the student body. Fast forward to today and that percentage has soared, with 12.89% of students at Pomona during the past academic year from other countries, hailing from nearly 60 nations. The growth in international enrollment has enhanced Pomona’s campus culture, creating a vibrant array of backgrounds and perspectives.

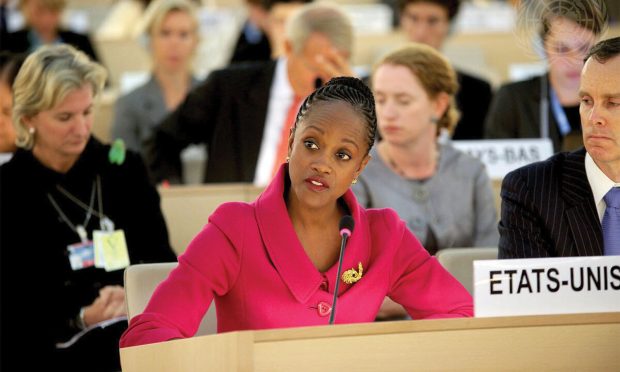

Living and studying with students from other countries provides an educational experience for U.S. students as well, says Esther Brimmer ’83, a foreign affairs expert who formerly was executive director and CEO of NAFSA: Association of International Educators, the largest nonprofit professional association devoted to international education.

“It’s extremely important for students in the United States to have the opportunity to study with students from around the world,” Brimmer says. “Many students will not be able to travel internationally. But it is a wonderful opportunity for students across the United States to benefit from learning from their colleagues in the classroom, their friends in the dorm, their friends on the sports team. It’s a great way for students to be able to get to know people from other parts of the world even if they do not or are not able to travel.”

Arriving Sight Unseen

International students sometimes arrive to begin their college careers without having so much as a campus tour or attending Admitted Students Day. Shortly after coming to Pomona as a first-year student, Hingad reached out to Assistant Vice President and Director of Admissions Adam Sapp to finally meet him in person after initially being drawn to Pomona after an older student from her high school, Rya Jetha ’23, chose it.

“I remember going home and searching it up, and suddenly everything began to click,” Hingad says. “I remember reading the statement, ‘the promise is in the place,’ and that is exactly why I applied—from small class sizes to warm weather (and people). I applied Early Decision without even visiting the campus.”

In that first face-to-face encounter with Sapp, a person she was only familiar with from afar, Hingad says she became an admirer of the way he described Pomona’s interdisciplinary education, explaining how the liberal arts approach allows knowledge to build on itself.

“What he said challenged me to think of knowledge in a way that everything just clicked,” says Hingad, explaining that the educational system in India is more rigid and requires a narrower area of focus. “Where I come from, people have their future set up from the 10th grade.”

Sapp is used to explaining the different approach at Pomona and many other U.S. colleges.

“For many [international] families, this might be the first time they hear words like liberal arts, interdisciplinary studies or guaranteed housing,” he says. “Often, we recruit in places where the higher education system works very differently from ours, so we are not just introducing a new philosophy of education, we are literally speaking a whole new language.”

Finding Talented Students

International students gathering in front of Bridges Auditorium.

Recruiting international students starts earlier for some of those reasons. Pomona often will begin to connect with students as early as ninth or 10th grade. Admissions officers traveling to other countries not only visit what are known as international schools—which generally have multinational students and multilingual instruction—but also public high schools, which typically offer that country’s national curriculum.

In addition, Pomona engages with government initiatives like EducationUSA, a U.S. State Department network of international student advising centers in more than 170 countries, as well as international nonprofits and foundations like the Davis Foundation and its United World College Scholars Program, the Grew Bancroft Foundation, the Sutton Trust and Bridge2Rwanda, among others. As an example of the effectiveness of those partnerships, Sapp says that every student admitted to Pomona’s Class of 2028 from Argentina, Uruguay, Egypt or Vietnam had a direct link to a global nonprofit partner.

“It’s important to us that we do work beyond traditional international high schools,” Sapp says. “There’s so much talent in the local high schools, and some of these high schools we just couldn’t access without the local outreach of our partners.”

Among Pomona’s longstanding partners is the Davis United World Colleges Scholars Program, which is linked to 18 United World College high schools around the world welcoming students from 160 countries. Their scholars study at almost 100 college and university partners across the U.S., including all five Claremont Colleges. During 2024-25, the foundation contributed more than $125,000 in scholarship support to Davis United World College scholars attending Pomona.

One marked difference between the international admissions process and that for U.S.-based domestic students is financial aid. For international students applying from outside the U.S., Pomona’s admissions process is what is called need-aware. Unlike the need-blind admissions policy employed for domestic applicants, for international students applying from abroad, the student’s or family’s ability to pay tuition is considered. Once admitted, however, all students receive the same type of aid package: 100% of demonstrated need is met with a package that includes a combination of Pomona grants and student work and, just like the packages for domestic students, does not include loans. In all, slightly more than half of international students at Pomona receive financial aid. By comparison, most U.S. colleges and universities do not offer significant need-based aid to international undergraduates.

“We’re incredibly lucky to have policies in place that ensure international students from a wide range of socioeconomic backgrounds have access to a Pomona education,” Sapp says.

Nationally, colleges suffered a “pandemic slump” in international student recruitment but those numbers have rebounded, in part because of a 35% increase in students from India, according to a recent Open Doors report sponsored by the U.S. State Department.

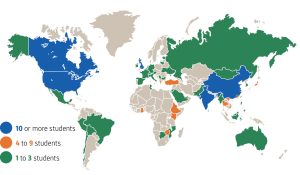

The top countries that sent students to Pomona for the past academic year were China (29 students), India (20), Japan (12), Greece and Kenya (11 each) and Canada (nine).

In total, 59 countries were represented by Pomona’s F-1 visa-holding students. (An F-1 visa allows a nonimmigrant to study in the U.S. as long as they are a full-time student enrolled in an approved academic program and are proficient in English, among other criteria.)

Student Support Services

Once an international student enrolls at Pomona, the College’s International Student and Scholar Services Office steps in to help with the F-1 visa process. Kathy Quispe, assistant director of international student and scholar services, notes that while her office directly supports students holding F-1 visas during their four years at Pomona, it also provides support to students who are U.S. citizens but grew up abroad. All international students, regardless of immigration status, are invited to the international student orientation. And all international students have the option of being paired with an International Student Mentorship Program (ISMP) mentor who will help them adjust to life at Pomona as well as life in the U.S.

Young Seo Kim ’26

While F-1 visa students share similarities with U.S. citizens who were born and/or raised abroad, they face a burden unique to them: hurdles of paperwork. The paperwork continues throughout their four years at Pomona. If they want to work on campus, that requires applying for a Social Security number. If they want an off-campus internship, that will require specific authorization to avoid being in violation of their F-1 visa status.

In addition, F-1 status has a big impact on an international student’s academic and career choices. “F-1 visa-holding students can work in the U.S. up to a year after graduation, as long as the job relates to their major, but for STEM majors it goes up to two years,” says Quispe. “This year, of our 33 graduating seniors, 27 are graduating in STEM.” Quispe adds that this makes Pomona a place for international students who major in STEM to still enjoy the full offerings of a liberal arts education.

Beyond helping students navigate government requirements, staff in the International Student and Scholar Services Office are fine-tuned to news affecting different parts of the world.

International students gathering for their end-of-year dinner in April 2023 to say a farewell to graduating seniors.

“While many of our students have connections to all parts of the world, our international students tend to be more impacted when there are world crises,” says Carolina De la Rosa Bustamante, director of the Oldenborg Center, Pomona’s language-focused residence hall, dining hall and center for other internationally oriented programs. “When there are geopolitical tensions or natural disasters, international students are the first population that we think of.”

When news of a recent attempted coup in Guatemala reached Quispe, she sought out Young Seo Kim ’26, an international student born and raised in Guatemala to Korean parents, to ask if she was OK.

“It was a very small action, but it was so considerate,” Kim says, describing the different types of support and help that she has received. “She made sure I was doing OK mentally and physically. She was making sure that I knew I had her support in case I needed to leave the college for an emergency,” she adds. “International students are far away from home, so having someone who understands your story and helps you no matter what we need at times is important.

“Obviously, you’re going to be homesick,” says Kim, who appreciates the special events organized by Pomona and ISMP during key times of the school year like fall break and spring break when many students leave campus—but others, like her, stay behind and tend to miss their families more during those times.

Kim recalls spending Thanksgiving on Pomona’s campus among international friends for an ISMP-hosted dinner. “They had different cuisines so people could feel like they’re back home,” says Kim, remembering how the Salvadoran and Chinese foods at one dinner included pupusas and other dishes that were similar to Guatemalan and Korean cuisines. “They had tortillas and fajitas and you could make your own small taco and that really reminded me of home.”

Hingad recalls her first year when she performed spoken-word poetry at an open-mic event on campus. Two years later, a lot has changed, but that feeling remains the same. Her work, titled “Home,” resonated deeply with many people. “The piece was about small impacts that people make and how they compound to make 91711 [Pomona’s ZIP code] a home,” she says. “It’s the shared experience of different people coming from different backgrounds with one thing in common: good parts of humanity.”

Like Hingad, many international students are making a choice that no one else in their families has made.

“Everyone knows we have a lot of students at Pomona who are trailblazers, but for our international students, I think they deserve just a little bit of extra credit,” Sapp says. “To travel five, six, sometimes even 7,000 miles away from home to pursue an education that might be totally different than what is offered in their home country—it astonishes me to think about how much bravery that requires. It’s also a vote of confidence in the Pomona education. We know how transformative this place can be, so working hard to open doors to talent around the world and educate the next generation of global leaders makes total sense.”

Timi Adelakun ’24

Timi Adelakun ’24 María Durán González ’24

María Durán González ’24 Phillip Kong ’24

Phillip Kong ’24 Alexandra Turvey ’24

Alexandra Turvey ’24