Masago Armstrong shaped the academic lives of generations of students as Pomona College registrar from 1955 to 1985.

Revered in campus lore, Masago Armstrong helped thousands of students stay on track during her 30 years as registrar of Pomona College. After leaving a $1 million gift for scholarships at her passing, Armstrong will continue to shape students’ lives for years to come.

The daughter of Japanese immigrants, Armstrong found her world upended in 1942 during World War II when her entire family was sent to a U.S. government incarceration camp, where her mother died. In time, Armstrong rebuilt her life and went on to influence the academic lives of generations of students during her tenure as Pomona College registrar from 1955 to 1985.

Coming from an administrator whose work unfolded behind the scenes, the bequest is a testament to Pomona’s close-knit community—and to the extraordinary nature of Armstrong, who passed away at the age of 102 in 2022.

“Masago Armstrong was known for her skill and diligence as registrar and for her kindness and care for Pomona students,” said Pomona College President G. Gabrielle Starr. “This endowed scholarship will honor her mother’s memory and support generations of students with financial help to attend Pomona.”

The gift through Armstrong’s estate builds on the smaller Towa Yamaguchi Shibuya Scholarship Fund that Armstrong launched in honor of her mother decades earlier.

Masago Shibuya Armstrong was born in Menlo Park, California, one of six siblings who worked on the family’s flower farm. Her parents, determined that all their children would attend college, saw most of them off to Stanford, where Masago graduated with a master’s degree in 1941.

At opposite page top, the Shibuya family before being incarcerated during World War II. Photo by Dorothea Lange.

Her father, Ryohitsu, and mother, Towa, were born in Japan and came to the United States in 1904. Masago’s father is said to have arrived with just $60 in cash and a basket of clothes. Together with his wife and children, the family built a thriving flower business renowned for its prized chrysanthemums.

The Shibuyas’ hard-won prosperity was interrupted by catastrophe in April 1942. Due to the executive order issued by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, the entire family was sent to temporary quarters at Santa Anita Park racetrack in Arcadia, California, and then moved to a detention camp for Japanese Americans at Heart Mountain in Wyoming. Tragically, her mother died there at the age of 51, and the family would not return to their Menlo Park home until April 1945.

After the war, Armstrong worked at Stanford University, where she met and married her husband, Hubert Armstrong. Together they moved to Claremont, where she was hired by the College in 1955. During her long career, Armstrong helped guide 8,752 students through to graduation.

Before Armstrong’s death and in celebration of her 100th birthday, Julie Siebel ’84 joined a group of alumni to share memories of Armstrong’s influence on their lives at Pomona and afterward. Siebel recalled how Armstrong knew her mother—Cynthia “Sue” Cudney Siebel ’59—who had attended Pomona—and also remembered Julie as a child growing up in Claremont.

“Masago’s warm welcome to me as a first-year in Sumner Hall really surprised my sponsor group because they had been told to fear her at registration,” recalled Siebel. “And later, when I applied to graduate school, the hand-calculated GPA on my transcript was a point of interest to the historians on my admission committee. I gave them the first hand-calculated GPA they had seen since computerized transcripts had become the norm, and they asked me about it. I assured them that Masago was more accurate than a computer.”

Beloved and respected by the Pomona community, Armstrong was known as a woman of gracefully opposing forces. She was kind and stern, patient and efficient, self-effacing and accomplished, mild and meticulous. Her memory for names and faces, majors and GPAs remains the stuff of legend. She was both a masterful student mentor and an exacting, indomitable college administrator.

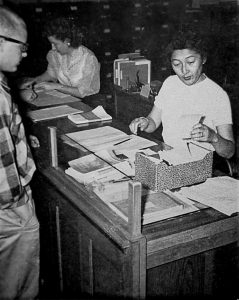

At bottom, Armstrong in action as registrar pictured in the 1957 Metate yearbook.

When she retired, Armstrong reflected on her career in an interview for Pomona College Magazine. “I like the detail. I think that is one of my strengths, and it’s absolutely necessary for the job. … And I haven’t denied myself the pleasure of meeting the students,” she said.

In the same magazine piece, then Associate Dean of the College R. Stanton Hales ’64 agreed. “She is the ideal registrar. She is efficient, patient and has a deep and sincere interest in every individual student,” Hales said.

Even decades after retiring, Armstrong stayed close to Pomona’s campus as a resident of the Mt. San Antonio Gardens retirement community a little more than a mile from Marston Quad.

Lily Shibuya, Armstrong’s sister-in-law, commented on the gift and the College’s plan to celebrate Masago and her enduring impact on Pomona: “To me the best epitaph that describes her is that ‘to know her was to love and respect her’ as she enriched everyone’s life that she touched. Thank you to Pomona College for honoring her in this special way.”