At the tender age of 17, many students are faced with decisions not only about where to apply to college, but also about what to study. At University of California and Cal State University system campuses in particular, the major that students apply for—and the competition within that applicant pool—can be the difference between acceptance and rejection.

At liberal arts colleges in general and Pomona College in particular, the educational approach provides opportunities for exploration, refinement of interests and the melding of different academic fields. Small classes and close relationships with faculty allow for collaborative learning with other students and attentive intellectual and career guidance from professors.

Here are the stories of six students and alumni and their searches for the intersection of their interests and talents.

Zoë Batterman ’24

When Batterman came to Pomona College from New Orleans, her interests lay in environmental analysis and philosophy. But taking linear algebra her first year with Shahriar Shahriari, William Polk Russell Professor of Mathematics and Statistics, shifted her trajectory.

“That class revolutionized what I thought about math,” Batterman says. “I really loved how creative it could be. It felt like a very powerful edifice where one can see how other people think.”

The camaraderie of the mathematics community also drew her in. Even online during the COVID-19 pandemic, Batterman met a group of people who were “very close friends,” and that community helped propel her into the mathematics major.

“Whereas I previously thought of mathematics as a foreign and inaccessible discipline, the collaboration and support shown in Pomona’s Mathematics Department demonstrated otherwise,” Batterman says.

Soon after deciding on the major, she began seeking research opportunities. Her sophomore year, Batterman worked on C*-algebras with Konrad Aguilar, assistant professor of mathematics and statistics.

Batterman then learned about the work of Professor of Mathematics and Statistics Edray Goins, which is motivated by the longstanding Inverse Galois problem. She was selected to participate in Goins’ Pomona Research in Mathematics Experience (PRiME) program, an eight-week residential research opportunity, the summer after her sophomore year.

Zoe Batterman ’24, center, with Talitha Washington, president of the Association for Women in Mathematics, and Professor Edray Goins.

Her work and accomplishments have led to three prestigious national awards in the past year: the Goldwater Scholarship, the Alice T. Schafer Prize for Excellence in Mathematics by an Undergraduate Woman and the Churchill Scholarship, which funds a year of graduate study at the University of Cambridge.

“I have watched her grow into a powerhouse of a mathematician,” says Goins.

Batterman appreciates the recognition because she notes that students at large research universities tend to draw more attention through math competitions and “have access to a lot more resources like graduate courses.”

Without those courses available to Batterman, Goins worked personally with her on graduate-level material that he had taught while a professor at Purdue University.

After graduating this spring, Batterman will head to Churchill College at Cambridge, where she will conduct full-time pure mathematics research with Professor Dhruv Ranganathan.

In the longer term, Batterman plans to earn a Ph.D. in mathematics, which ideally will allow her to become a university professor.

“I want to do math and join the community and the conversation,” she says.

Betsy Ding ’24

Ding’s Instagram account, @paintpencilpastries, showcases lush floral arrangements, glossy ceramic pieces and food sumptuously arranged into veritable works of art, all formed by her hands on campus.

Ding considered attending culinary school at several points. In her teens, she already had amassed 30,000 followers on her TikTok cooking channel, published a recipe in Taste of Home magazine and formed paid partnerships with brands.

After arriving at Pomona, Ding decided to major in cognitive science and minor in studio art, while also taking classes in engineering, computer science and philosophy, among other disciplines, at the various Claremont Colleges. She laid to rest the idea of pursuing food professionally (thinking her temperament was better suited to other careers).

But food continued to play a considerable role in her life: as an outlet for stress, as a way to bring friends together and as a vehicle for satisfying her cravings.

Courses such as Food and the Environment in Asia, Anthropology of Food and Foundations of 2D Design contributed to her development as a chef and consumer.

“Food is something that everyone cares about and loves, but it’s often not seen through the lens of history, environmentalism, culture and cultural exchange and economics,” says Ding. “In my classes I’ve learned about industrialization, chefs’ roles in creating cultural cuisines, as well as agriculture and the role of food in the environment.”

In the fall of 2023, Ding applied for a Student Creativity Grant through the Hive—more formally known as the Rick and Susan Sontag Center for Collaborative Creativity—to design and prepare a nine-course tasting menu dinner.

When it was time to eat, eight fellow students and two staff members from the Hive took their seats in the Dialynas Hall living room, adjacent to the kitchen. The table was set with plateware carefully curated to enhance the dining experience and paired with paper menus that Ding designed.

She also included an information sheet with the stories behind each course: why she chose certain ingredients, how the food spoke to her own upbringing, and her relationship to the dish.

For the next two hours, guests were treated to a feast for the eyes and taste buds.

Ding credits the visual presentation of her food to her art classes at Pomona, which taught her “how to consider composition, color and design.”

As she prepares to graduate from Pomona, Ding reflects on how the College has shaped her and others to be “independent thinkers.” Taking classes in so many disciplines has broadened her mind, and food has been just one area in which she has been able to express her creativity and resourcefulness.

Kirsten Housen ’23

Housen came to Pomona College from the San Francisco Bay Area for the opportunity to play varsity soccer while studying any subject of her choice. Although injuries and the COVID-19 pandemic curtailed her soccer career, her time at Pomona succeeded in launching her vocation in civil and environmental engineering.

Housen was aware of Pomona’s 3-2 combined plan in engineering—which allows students to receive a bachelor of arts degree from Pomona College and a bachelor of science from Caltech or Washington University in St. Louis after a combined five-year program—when she arrived. While unsure if she would pursue that path, she was quickly drawn to the physics department. Faculty members were inviting and made the subject accessible and enjoyable, she says.

Settling on a physics major opened her to pursuing the 3-2 program. Fitting in the pre-engineering requirements in addition to classes toward the physics major and Pomona’s general education requirements—all in three years—required careful planning.

Despite the structure, Housen says she still had ample room to gain a broad liberal arts education.

“I always had a really nice balance of the technical and the philosophical and creative,” she says.

When it came time to transfer, she chose Washington University.

Janice Hudgings, Seeley W. Mudd Professor of Physics, taught three of Housen’s physics courses at Pomona and says that she was confident that Housen would excel at Washington University: “Building on her liberal arts background, Kirsten leaned into the advanced engineering courses,” Hudgings says.

Among many other accolades at Washington University, Housen made the dean’s list, was selected as the Lee Hunter Scholar in the School of Engineering and received the Award of Excellence in Technical Writing for Social Impact for her paper on the water quality impacts of fast fashion in developing countries.

Housen in a chemical engineering/environmental engineering lab at Washington University in St. Louis.

“The process of researching and writing this paper underscored how valuable the liberal arts education is and the wonderful writing and critical thinking foundation that Pomona provides to its students,” says Housen, who is now enrolled in Stanford University’s master’s program in civil and environmental engineering.

She looks back at her time at Pomona with appreciation.

“It was a really great opportunity to have the option to go into an engineering route while still having the liberal arts foundation and getting to take all the different kinds of courses that Pomona offers,” she says.

Housen’s message to Pomona students: “Explore and use the opportunities available to you. Figure out what you really want to do and what makes you motivated. Pomona is a great place to learn. You’re around people with such interesting ideas and opinions.”

Dylan McCuskey ’23

McCuskey chose Pomona so he could study both physics and English without getting pigeonholed into either. Little did he imagine, however, that those two fields would come together for him as he prepares to publish an English paper in a literary journal by employing a theoretical physics analogy.

His passion for physics and English came together his junior year when he was taking Legal Guardianship and the Novel with Sarah Raff, an associate professor of English, and General Relativity with Professor of Physics Thomas Moore.

As McCuskey read Charles Dickens’ Bleak House, “a really complex, 900-page, twisty turning novel with two narrators,” for his English class, he realized there was a concept in his physics class—which studied space, time, gravity and theoretical astrophysics—that he could superimpose on the narrative structure of the novel “to better understand what was going on between the two narrators.”

One of the narrators is an impersonal, omniscient voice, which he designated as a “space” narrator, “moving across the city of London and observing everything that happens in the current moment,” he says. The other narrator is a first-person character in the story, which McCuskey assigned as the “time” narrator, “driving the passage of time and guaranteeing a future from a single point in space.”

For his final assignment, he wrote a 25-page paper titled “Bound by Time and Place: The Spacetime Guardianship of Bleak House.” Raff was so impressed by it that she encouraged him to submit it to an academic journal to be published.

McCuskey and Raff worked together for several months to revise the paper, and in fall 2022 the essay was accepted by The Dickensian journal for publication in early 2024.

“In the field of English, it is extremely rare for an undergraduate to publish in a professional peer-reviewed journal,” says Raff. “In nearly all cases, it takes many years of graduate study to write for a scholarly journal in a literary field.”

For McCuskey, the experience of writing and publishing the article has been validating. “I’ve been interested in physics and English for a long time, but I haven’t had projects that do both,” he says.

Looking ahead, McCuskey would like to continue to combine his physics major and English minor in his career. He is planning on attending graduate school for physics and eventually doing research and teaching at the college level.

To teach, McCuskey says, “You have to have the science knowledge but also the humanities communications skills.”

Ruben Murray ’19

When Murray wrote his senior thesis on the small East African country of Djibouti, the international relations major didn’t expect to end up there two years later as a foreign service officer for the U.S. State Department.

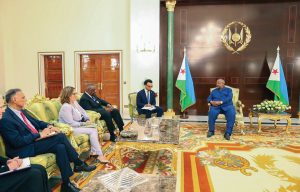

Having dreamed as a child of becoming a diplomat, Murray was able to cut his teeth on his first post, performing such tasks as interpreting for a meeting between the Djibouti president and the U.S. secretary of defense, joining a search and rescue mission for stranded migrants in the desert, and serving as the interim chief of his section.

Taking classes on African history with Makhroufi Ousmane Traoré, an associate professor of history and Africana studies, as well as conducting research on African politics and development with Pierre Englebert, H. Russell Smith Professor of International Relations and Professor of Politics, helped Murray find his niche in African security studies and focus his senior thesis on Djibouti.

When it came time for Murray to rank his choices for his first assignment as a foreign service officer, he included Djibouti in a list of about 20 countries. As it turned out, Djibouti had an immediate need for a political officer.

Murray’s qualifications also included his fluency in French, having grown up in France with a French and Spanish mother and an African American father.

The job included a lot of writing, says Murray, and his education at Pomona prepared him well.

He took advantage of the Center for Speaking, Writing, and the Image regularly, visiting weekly for help with class assignments. When writing reports now, he says, “I still go through the same mechanism that I did when I was submitting my papers to the Writing Center.”

One of the most surreal moments of his two years in Djibouti came when U.S. Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin arrived for meetings with the country’s president. When it became clear that Murray was the most qualified person to provide translation, he says he was “kind of thrown into the situation.”

“That’s not something that’s written in your contract,” he says.

But it did land him in a historic moment—Secretary Austin’s first official trip to Africa.

Before Murray wrapped up his post in Djibouti, he received the U.S. State Department’s Superior Honor Award for his sustained extraordinary performance in Djibouti.

Having found what he was passionate about “as opposed to doing something because I thought it would look good for employers in the future,” Murray’s advice for current students is, “Find what moves you.”

Murray’s views are his own and do not reflect those of the Department of State.

- Murray, left of flag, provides translation between U.S. Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin and the president of Djibouti. Ismail Omar Guellah, during Austin’s first official trip to Africa.

- Ruben Murray ’19, right, during a U.S. Navy Maritime Expeditionary Security Squadron patrol in Djibouti.

Daniel Velazquez ’25

The day before the MexiCali Biennial Exhibition was set to open at The Cheech Marin Center for Chicano Art & Culture, Velazquez and Samuel White ’23 labored side-by-side with Rosalia Romero, assistant professor of art history, to put the finishing touches on the show.

For all of them, the opening would be a culmination of months of curatorial work and research.

Romero was an organizer for a pair of exhibitions at The Cheech in Riverside, California. The first was Land of Milk and Honey (the most recent iteration of the MexiCali Biennial) which focused on concepts of agriculture in California and Mexico. An adjacent gallery showed a corollary presentation, MexiCali Biennial: Art, Action, Exchanges, which chronicles the history of the MexiCali Biennial from 2006 to the present.

Velazquez’s primary task was to conduct research with the Hispanic Reading Room of the Library of Congress to create a story map—an interactive digital storytelling tool—on Land of Milk and Honey. The story map uses photographs, illustrations and interviews to tell the deeper history of four pieces in the exhibition.

This research equipped Velazquez well to serve as a docent at the museum for the exhibitions. They also wrote wall texts and helped curate and install the shows.

Velazquez came to Pomona from Chicago as a Posse Scholar and plans to double major in Chicana/o-Latina/o studies and sociology.

In their first-year writing seminar about Southern California murals taught by Romero, Velazquez says that “seeing how Professor Romero was able to bring the political side of art and connect it to social problems and movements made me really interested in art.” After enrolling in Romero’s Introduction to Latin American and Latinx Art course next, Velazquez asked to do research with her.

Velazquez says of the research experience: “It was very rewarding and also very refreshing to be not just in the museum but a museum for people like me and working on an exhibit that’s about experiences that make me think about my family’s experiences.”

Velazquez hopes to work in museums as a career and is especially interested in archival and curatorial work. The idea of presenting research via an exhibition (versus through, say, a paper) appeals to Velazquez.

“While I love that I would be researching and studying and probably teaching, you can do both; Professor Romero is a professor and is also doing museum work,” Velazquez says.

Daniel Velazquez ’25, right, and Samuel White ’23 worked with Assistant Professor Rosalia Romero on the MexiCali Biennial exhibition at The Cheech.