For the young and entrepreneurial, launching a startup with your college friends is a natural thing to do. You’ve spent countless hours studying, hanging out and crafting ideas together in an environment that is ready-made for inspiration.

Pomona College is in the midst of a mini-surge of Sagehen startups, part of an entrepreneurial scene that reaches from the Bay Area to New York and beyond. Lately, Southern California, too, has seen a wave of new ventures in areas such as tech, with dozens of incubators and accelerator programs launching, and venture capitalists taking notice and investing in promising young companies.

Right here on campus, business-minded students are working to make entrepreneurship more than a niche. “There are very few professions in the world that are more liberal-artsy than being a young entrepreneur,” says ASPC President Darrell Jones III ’14, who is already on his second entrepreneurial effort. He is part of a campus group called Pomona Ventures that encourages entrepreneurship and, with support from alumni, helps students line up seed money to get started.

But whether a startup is taking off in Claremont, the Big Apple or on a windswept Alaskan island, the shift from dorm-room dreams to a successful enterprise requires stamina, passion—and capital. Beginning entrepreneurs need to sort out their roles within their new organization, find ways to handle disagreements and figure out ways to support each other, all while bringing in the funds to keep the lights on.

Finding their Way

Jesse Pollak, Mark Hudnall and Brennen Byrne.

“The habit we keep having to break ourselves from is assuming that there are rules or guidelines or some path to follow. In school, there’s a path that’s laid out for you from matriculation to graduation. Starting a company isn’t nearly as straightforward,” says Brennen Byrne ’12, CEO of Clef.

Now based in the Bay Area, Byrne began working with Mark Hudnall ’13 and Jesse Pollak ’15 while they were at Pomona. They started off interested in how websites share information with each other, and ways to improve that process. Within weeks, though, they focused in on the issue of identifiers and concluded that “passwords were the problem.” That led to Clef, a mobile app that replaces online usernames and passwords. The app identifies users by their phones, so they never need to remember or type anything when they log into a site.

One area where the startup has tried many avenues is in marketing. They first followed typical routes, trying to get the market, consumers and press to pay attention through social media. But the Clef crew got real traction when they tried something different. This July, they recruited 15 other similar identity companies, a handful of consumer rights groups and a few celebrities to launch a “Petition Against Passwords.” Their move on the petition landed them attention from The Economist, the BBC, Los Angeles Times and others. “We were suddenly a dominant voice in a conversation that we hadn’t had access to before, and we started getting emails from our dream customers asking for more information about Clef and how they could start using it. By stepping outside of the expected checklist, we were able to have a much bigger impact,” says Byrne.

Next step: Byrne and Co. are looking to apply their work in the realm of e-commerce checkout, which holds more competition, Byrne says, but also more lucrative opportunities. “Every day there are a million different opportunities for us to be pursuing or directions for us to be going in, and we have to navigate that in a completely different way. College throws hard problems at you, but in a startup you have to find the right problems to solve,” says Byrne, an English and computer science major.

Partners on the Roller-Coaster Ride

Tom Vladeck, Ben Cooper and Geoff Lewis.

Geoffrey Lewis ’08 launched Building Hero last year with Ben Cooper ’07 and Tom Vladeck ’08. They had become great friends at Pomona, largely, Lewis says, “because of our shared passion for energy-efficiency.”

The company started in San Francisco pursuing the niche of installing LED lighting in businesses such as boutiques, art galleries and hotels. Their pitch: energy-efficient lighting saves customers’ money and benefits the environment without sacrificing aesthetics, and at the start, they were greatly aided by a local utility offering generous rebates for businesses that switched to energy-efficient lighting.

However, the rebate program was so generous that it ran out of money on several occasions

“As a small startup, it was hard for us to deal with this type of uncertainty,” says Lewis. So they made a “strategic decision” to expand into New York City, which, like San Francisco, has high population density, lots of small retail shops and high electricity prices, which make LED more appealing.

That wasn’t the only shift. With the end of the rebates, the Building Hero crew realized that many small retailers weren’t willing or able to pony up the up-front costs to switch over to LED. So Building Hero switched over to a different model, in which businesses got their lights right now but repaid the cost over time through a monthly service fee, which included maintenance.

Lewis, however, points out that constant change is just part of the ride for a startup: “That uncertainty: Is this company going to exist years from now? That’s what makes it exciting to come to work.”

“Startups are a crucible; it’s very hard to create something new in the marketplace, and that creates a lot of stress on the founders of any new venture. I think coping with that stress together has had a huge effect on bringing us closer together.”

Arye Barnehama ’13 and Laura Berman ’13 met while studying cognitive science at Pomona. Sharing that interest led them to become fast friends. And it eventually led them to launch Melon, which consists of a lightweight headband and a mobile app that employs EEG technology to get a read on all those neurons firing in your pre-frontal cortex, use the data to measure focus and “give you personalized feedback to help you improve.” As they work, Berman and Barnehama have had to learn how to support each other. “As entrepreneurs you’ll face a lot of ups and downs,” says Berman, CEO of the firm based in Santa Monica, Calif. “During the good times, it’s great to share those experiences with a close friend. When you find yourself in harder times, it’s great to have somebody whom you know how to support and who, in return, knows how to support you best.”

Work-Life Balance

Laura Berman and Arye Barnehama

With no school calendar full of classes, activities and built-in breaks, startup entrepreneurs must adjust to setting their own schedules. It’s their own willpower that must see a team through product launches, long hours and thorny problems. On the other hand, there’s a temptation to skip sleep and ignore all other parts of life.

“When we started our own company, we felt a lot of pressure to work constantly— as close to 24/7 as humanly possible,” recalls Berman. “It’s easy to get into a mindset where you think, ‘Every moment that I’m not working on this, nobody else is either,’ and you become scared to take a break.”

Many entrepreneurs have this type of mentality at first, believing that a round-the-clock schedule will lead to faster success. But the accompanying stress can lead to greater tension and mistakes.

The Melon team found greater work-life balance after working as a startup in residence at a top design firm IDEO (most famous for designing the first Apple mouse). There, they learned that innovation comes easiest in a creative space where people are working on a variety of projects. One of their mentors at IDEO advised them to favor curiosity over expertise when hiring, and to designate time every week for creative activities unrelated to Melon.

“This is different from college, where you have a pretty set schedule of assignments and deadlines. Learning to create a schedule where we worked efficiently and didn’t overload all the time definitely took a while,” Berman says. It seems to be paying off: Melon has raised nearly $300,000 through Kickstarter, and venture capitalists and angel investors have provided additional funding. The pair, previously based in Massachusetts, was recently honored among 25 top entrepreneurs under 25 by the Boston Globe.

Communication and Differences

Zach Brown ’07 grew up in the Southeast Alaska town of Gustavus (pop. 350), too small to even have a McDonald’s or a movie theatre, and so remote you can only get there by plane or boat. Perhaps it was the very small town feel that made Brown value kinship and trustworthiness in others. It also made him want to build something in his home state.

Brown and three fellow graduate students from Stanford University are founding the Inian Islands Institute, devoted to research and experiential education on a breathtaking five-acre parcel, set on a pristine island and known locally as the Hobbit Hole. The opportunity arose when Brown family friends, who have owned the isolated spot for decades, decided to put it up for sale.

As Brown and his partners envision it, the school will bring students from various universities to Alaska for field courses focused on ecology. Participating students will have an opportunity to catch their own salmon, drink rainwater and harvest their own food in a breathtaking setting of glaciers, fjords and temperate rain forest. The institute is nonprofit, but many of the challenges, trials and triumphs of a new business startup may apply to their organization as well. To figure out their roles, Brown says his team fell into categories of expertise pretty naturally: “We had one person most interested in marine issues (myself), one most interested in terrestrial issues, one for management/governance and one for conservation.

Zach Brown

These pretty well covered the themes we want to address in our school.” Still, making the institute a reality will be a huge undertaking for the foursome. “At first, we were just kicking around ideas over evening beers, and there was nothing at stake. Nothing to lose. It was a lot of fun. But as the vision has grown, we all realize the sheer scale of what we’ve embarked on, and as we begin to internalize what it could mean for our careers, some tensions have flared at times.”

I think that’s natural, and we’ve always gotten past them. It’s really important to have regular check-ins, face to face, and to be very open and honest with each other. It’s better to voice your concerns to the group right away, before they have a chance to fester. I think that’s true of any relationship: Communication is key.”

Even though constant harmony might seem appealing, Clef founder Byrne points out that it’s actually a good thing to not always agree.

“Young companies are full of really bad ideas and bad decisions, and it’s easier to make more of them, if everyone agrees on everything,” he says. “One of the things I’ve been really surprised by is how important it is for us to disagree. You have to disagree to tackle problems from different perspectives.”

Knowing When to Say When

Inevitably, many entrepreneurial ventures won’t make it in the first try. Lewis and Vladeck, decade-long friends who had even trained for a triathlon together, had to have a difficult talk about Building Hero this September. (Cooper had already moved on.)

“Energy-efficiency nerds,” as Lewis puts it, loved their LED financing model and its similarity to the way many consumers buy solar power. Potential customers weren’t as thrilled, though, as the pair struggled to build trust and convince strangers to buy into their innovative, energy-saving plan. “What’s hard for us is we got some positive feedback, but not enough to invest the next five years of our lives,” says Lewis. So it was time for the talk. “It was pretty much just a joint decision,” says Lewis. “We spent a long time kind of debating it with each other, having conversations about how we felt.”

Even though they decided to end that business, neither Lewis nor Vladeck expects this will be their last startup. They want to learn from their mistakes and press ahead. “This wasn’t our last chance to change the world,” says Lewis. “This was just our first chance.” — Mark Kendall contributed to this story.

FIRST, SOME BACKGROUND. As it turns out, I have an unusual perspective on all this. In the fall of 1992, I transferred into Pomona as a sophomore, hoping to play on the basketball team while preparing for a career in journalism. Mike was one of the first players I met. He made quite an impression. One memory stands out: an informal pickup hoops game at Rains Center, early that fall. Most of the team was there.

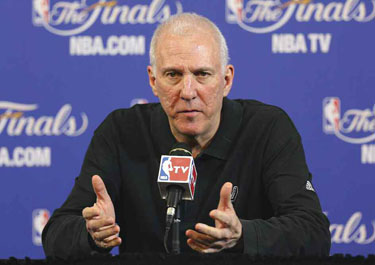

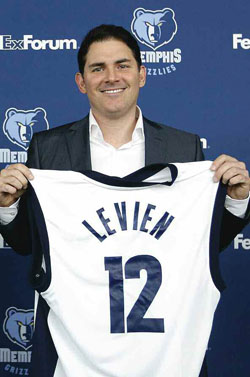

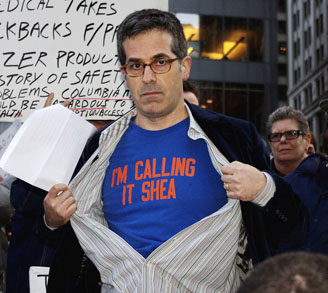

FIRST, SOME BACKGROUND. As it turns out, I have an unusual perspective on all this. In the fall of 1992, I transferred into Pomona as a sophomore, hoping to play on the basketball team while preparing for a career in journalism. Mike was one of the first players I met. He made quite an impression. One memory stands out: an informal pickup hoops game at Rains Center, early that fall. Most of the team was there. OF THE THREE, Popovich’s NBA ascent occurred first. His story is also the best-known. At Pomona, he turned around the Sagehen program, taking a team that was 2-22 in his first season and, within six years, leading it to a SCIAC title and a NCAA Division III Tournament berth. After spending a year as a volunteer assistant to Larry Brown at Kansas, he rejoined Brown with the Spurs, as an assistant. After a stint with the Golden State Warriors, he ended up back in San Antonio, and eventually became the general manager. In 1996, he named himself head coach. It’s a title he’s held ever since.

OF THE THREE, Popovich’s NBA ascent occurred first. His story is also the best-known. At Pomona, he turned around the Sagehen program, taking a team that was 2-22 in his first season and, within six years, leading it to a SCIAC title and a NCAA Division III Tournament berth. After spending a year as a volunteer assistant to Larry Brown at Kansas, he rejoined Brown with the Spurs, as an assistant. After a stint with the Golden State Warriors, he ended up back in San Antonio, and eventually became the general manager. In 1996, he named himself head coach. It’s a title he’s held ever since. So far, Jason says he’s enjoying the job. He keeps tabs on Budenholzer, whom he remembers as “the best competitor on the team” at Pomona, and still occasionally employs maxims he learned from Katsiaficas, including “be quick but don’t hurry.” “To me, Pop’s success made the NBA world seem more accessible and smaller,” he says of the Pomona connection. “And the time I spent on the team, I tried to learn as much as I could about the game. I really tried to suck it all in, because I knew Kat got much of his stuff from Pop.”

So far, Jason says he’s enjoying the job. He keeps tabs on Budenholzer, whom he remembers as “the best competitor on the team” at Pomona, and still occasionally employs maxims he learned from Katsiaficas, including “be quick but don’t hurry.” “To me, Pop’s success made the NBA world seem more accessible and smaller,” he says of the Pomona connection. “And the time I spent on the team, I tried to learn as much as I could about the game. I really tried to suck it all in, because I knew Kat got much of his stuff from Pop.”

Noah returned to the firm as a cofounder after graduation—his brothers only had a few coffee-service customers at that point—and two years later, Joyride Coffee has carved out a profitable new market providing top-notch roasts in the workplace. The relatively inexpensive perk of fancy coffee yields big appreciation from workers—that’s Noah’s pitch. And it’s working. Joyride was turning a profit by the end of their first year and, now, with 175 clients (coming from well beyond their original tech niche), the Belanich bros are the ones who need the caffeine.

Noah returned to the firm as a cofounder after graduation—his brothers only had a few coffee-service customers at that point—and two years later, Joyride Coffee has carved out a profitable new market providing top-notch roasts in the workplace. The relatively inexpensive perk of fancy coffee yields big appreciation from workers—that’s Noah’s pitch. And it’s working. Joyride was turning a profit by the end of their first year and, now, with 175 clients (coming from well beyond their original tech niche), the Belanich bros are the ones who need the caffeine.

AT MONROVIA HIGH, more than half the students are Latino, one of the groups hurt the most by cuts to arts classes. A 2011 report published by the National Endowment for the Arts showed that participation in childhood arts education has been on the decline since the early 1980s. Latinos have the lowest levels of arts training, 26 percent compared to 59 percent for their white peers, according to NEA’s 2008 Survey of Public Participation in the Arts.

AT MONROVIA HIGH, more than half the students are Latino, one of the groups hurt the most by cuts to arts classes. A 2011 report published by the National Endowment for the Arts showed that participation in childhood arts education has been on the decline since the early 1980s. Latinos have the lowest levels of arts training, 26 percent compared to 59 percent for their white peers, according to NEA’s 2008 Survey of Public Participation in the Arts.

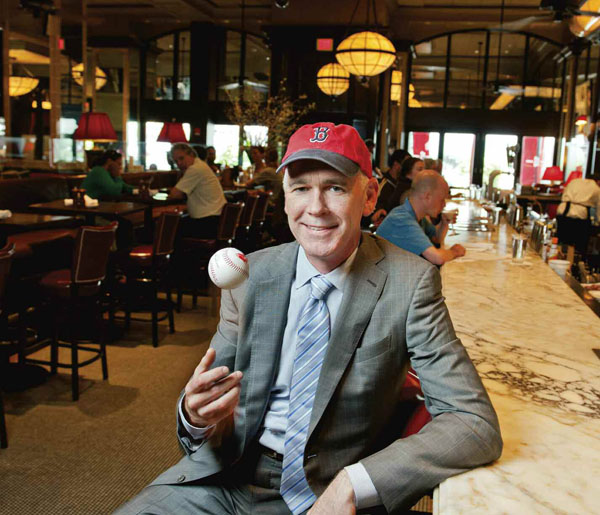

ut Luery can be a “stubborn cuss,” as a friend bluntly puts it. For him, love of family and love of baseball are inextricably linked. Baseball is not just a pastime, it’s a legacy—one that he inherited from his own father and “baseball buddy,” Robert Luery, who took him to the World Series at Yankee Stadium in 1963 when he was 8. Sure, the Dodgers with Sandy Koufax on the mound swept the Yankees that year, and little Mike cried all the way home, but baseball had gotten in his blood.

ut Luery can be a “stubborn cuss,” as a friend bluntly puts it. For him, love of family and love of baseball are inextricably linked. Baseball is not just a pastime, it’s a legacy—one that he inherited from his own father and “baseball buddy,” Robert Luery, who took him to the World Series at Yankee Stadium in 1963 when he was 8. Sure, the Dodgers with Sandy Koufax on the mound swept the Yankees that year, and little Mike cried all the way home, but baseball had gotten in his blood. In the end, father and son grew closer, and wiser. Matt learned to savor the slow pace of baseball games and really admire Jimi Hendrix. (“Dad, you may be a dinosaur but you rock.”) And Mike learned to be more flexible as a father, less quick to condemn, more willing to accept the differences between generations. From his son, he learned the “value of serendipity,” of going places without a compass, doing things without a blueprint: “Dad, the beauty of the trip is sometimes you get lost and you end up in a better place.”

In the end, father and son grew closer, and wiser. Matt learned to savor the slow pace of baseball games and really admire Jimi Hendrix. (“Dad, you may be a dinosaur but you rock.”) And Mike learned to be more flexible as a father, less quick to condemn, more willing to accept the differences between generations. From his son, he learned the “value of serendipity,” of going places without a compass, doing things without a blueprint: “Dad, the beauty of the trip is sometimes you get lost and you end up in a better place.”

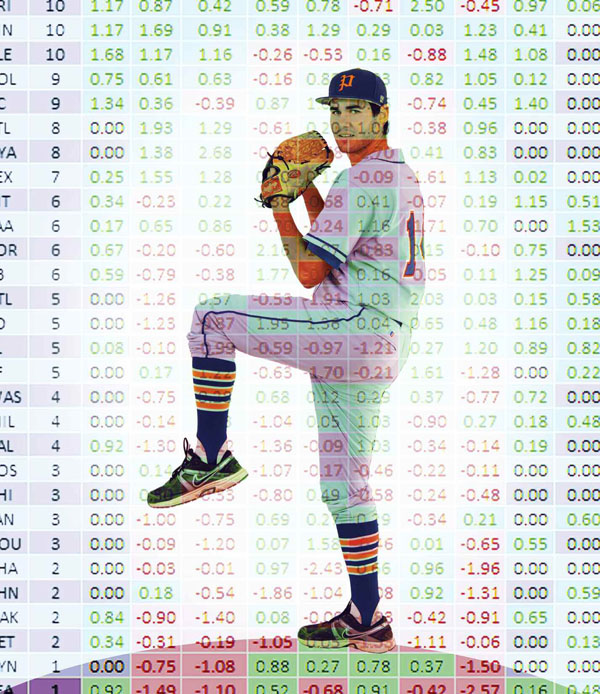

Statistics always have been important in baseball, but in recent decades the familiar stats such as batting average, ERA (earned-run average) and RBI (runs batted in) have been supplemented by an alphabet soup of acronyms, all trying to quantify aspects of the game. There’s WHIP (walks and hits per inning pitched) WAR (wins above replacement) BABIP (batting average on balls in play) and FIP (fielding-independent pitching) and those are just some of the more well-known ones.

Statistics always have been important in baseball, but in recent decades the familiar stats such as batting average, ERA (earned-run average) and RBI (runs batted in) have been supplemented by an alphabet soup of acronyms, all trying to quantify aspects of the game. There’s WHIP (walks and hits per inning pitched) WAR (wins above replacement) BABIP (batting average on balls in play) and FIP (fielding-independent pitching) and those are just some of the more well-known ones.