PHANTOM OF THE FOOTHILLS

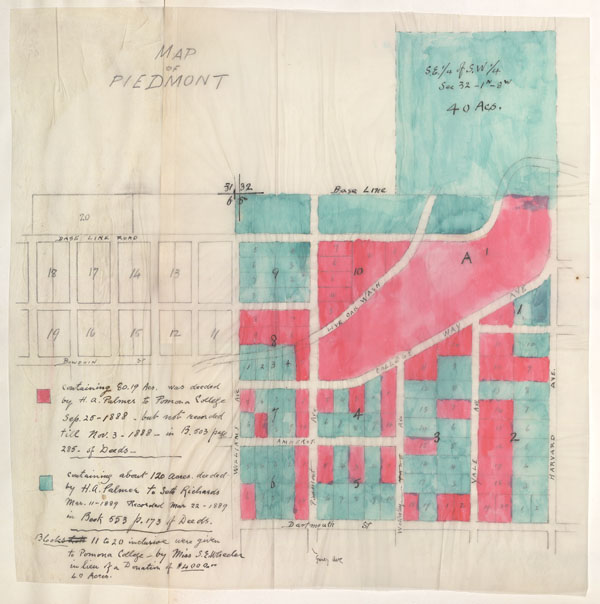

Planned as the original building site for Pomona College, Piedmont is the college town that never was.

For a place that never really existed, Piedmont turned out to be surprisingly easy to find.

The would-be burg dreamed up long ago as the permanent site for Pomona College couldn’t even be called a ghost town: Little more than a cornerstone was ever put in place, and even that was eventually moved away. Still, all the historical hubbub surrounding the College’s 125th anniversary piqued my curiosity about the location the Pomona Progress all those years ago declared was just right for the future college: “No sightlier spot could have been selected. The tract is … the very perfection of Southern California.”

Then came a real estate crash, and, soon after, an offer from the nearby struggling settlement of Claremont, which had an empty hotel to offer the College. After some tussling, the Piedmont plan was dropped for good, and the never-built town became just one of many SoCal settlements that didn’t make it past maps.

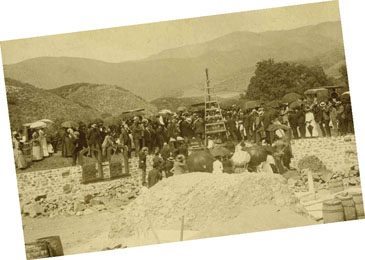

There remained, however, a photo from the September day in 1888 when hundreds of people gathered at the base of the foothills north of Pomona for the cornerstone ceremony. That old black and white helped lead me back to the spot known as Piedmont Mesa and its faint traces of the College’s beginnings.

There remained, however, a photo from the September day in 1888 when hundreds of people gathered at the base of the foothills north of Pomona for the cornerstone ceremony. That old black and white helped lead me back to the spot known as Piedmont Mesa and its faint traces of the College’s beginnings.

Next I turned to the tomes. The histories of the College—particularly Frank Brackett’s Granite and Sagebrush—were quite clear in placing the Piedmont Mesa at the mouth of Live Oak Canyon, a locationI know well having driven through it at least a hundred times.

So my editorial co-conspirator Mark Wood and I set off to do a little legwork and pinpoint Piedmont more precisely. Once there, we called up that old photo of the cornerstone ceremony on his iPhone.

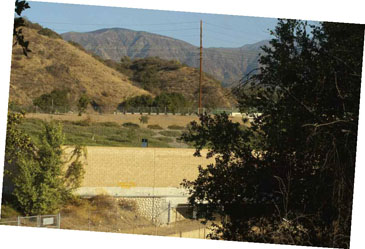

Even on the little screen, it was easy to line up the old view with the present one, since the hills had changed so little in 125 years. Comparing the two views, it looked to us like the site of the original cornerstone—later relocated—might just lie beneath the 210 Freeway, which today slices through the site.

Even on the little screen, it was easy to line up the old view with the present one, since the hills had changed so little in 125 years. Comparing the two views, it looked to us like the site of the original cornerstone—later relocated—might just lie beneath the 210 Freeway, which today slices through the site.

The street names bore witness to history as well. We were standing near the intersection of Piedmont Mesa Road and College Way. And then came the twist: Looking closely at the markings on those street signs, and later checking with the map, I couldn’t help but notice that even the original site dedicated to become a permanent home for Pomona College wound up within the city limits of … Claremont.

NEW TRACKS, OLD PATHS

When Dan Hickstein ’06 set out on an adventurous quest to chart the mountain-bike trails of Colorado, he ran smack dab into the state’s wild mining past.

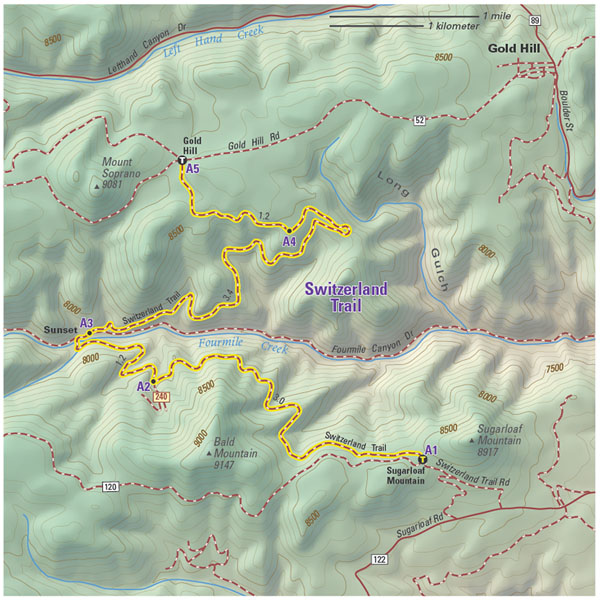

- Map by Mike Boruta / Fixed Pin Publishing

Dan Hickstein ’06 recently took a year-long “sabbatical” from the chemical physics Ph.D. program at the University of Colorado at Boulder to ride the trails and write the definitive guidebook to mountain biking in the rustic realm he now calls home.

Good maps were key to his quest. The outdoors adventurer, who earlier studied x-ray crystallography on a Churchill Scholarship to Cambridge, was unsatisfied with other Colorado biking guidebooks that contained hand-drawn maps that would leave him and his friends lost in the woods. Equipped with GPS, he set out to gather all the raw data that the book’s cartographer needed to get the maps just right.

Dan Hickstein ’06 in the Gold Hill, Colo., area. (Photo by Craig Hoffman.)

Naturally, he also had to ride every single trail, and that’s when he ran into something he didn’t expect. Many of those awesome, high-altitude rides led him smack dab into Colorado’s colorful past. You might think of mountain biking in the Rockies as a series of rugged trails, breathtaking views and run-ins with the weather—and it was all those things. But on the trails Hickstein also encountered closed-off mine shafts, “creepy, abandoned mining buildings” and once-bustling towns that had all but disappeared.

Over and over, he kept running across the remnants of the state’s mining rush in the late 1800s, later waves of mining, and the remains of various “crazy schemes,” including railroad tunnels blasted through 12,000-foot-high ridgelines and opulent summer resorts that are now long abandoned.

This convergence of mountain biking and history makes sense. Years ago, miners and engineers forged new paths through the mountains, and given the difficulty and danger involved in making them, those trails would remain of use long after. On the Switzerland Trail, pictured here, near what Hickstein calls the “quasi-ghost town” of Gold Hill, the mountain biking trail follows a path created over 150 years ago for a narrow-gauge railroad that once served mining towns. “So, when you ride the trail, you’re following the same path as the prospectors who rode the train up into the mountains with the hopes of striking it rich,” writes Hickstein.

Hickstein does concede that his brushes with history sometimes slowed the book project down. He’d ride past rustic ruins and later look them up to discover the settlement once had been filled with hotels, bars and brothels. He’d get lost in reading about some little town and how silver prices had shot up and then crashed after the Sherman Silver Purchase Act and … then he’d notice three hours had passed by and “Oh, man, I’ve got nothing done.”

Fortunately, he was able to include some of the historical tidbits—along with 118 maps—in his recently published book, The Mountain Biker’s Guide to Colorado (Fixed Pin Publishing). Hickstein is now a fourth-year grad student at University of Colorado, where he studies how ultrafast lasers can be used to make super-slow-motion movies of chemical reactions. But after a long day in the lab, Hickstein still finds time to ride the trails, sometimes even bringing along his own tome and its trusty maps.

Fortunately, he was able to include some of the historical tidbits—along with 118 maps—in his recently published book, The Mountain Biker’s Guide to Colorado (Fixed Pin Publishing). Hickstein is now a fourth-year grad student at University of Colorado, where he studies how ultrafast lasers can be used to make super-slow-motion movies of chemical reactions. But after a long day in the lab, Hickstein still finds time to ride the trails, sometimes even bringing along his own tome and its trusty maps.

THE COMMON-SENSE CARTOGRAPHER

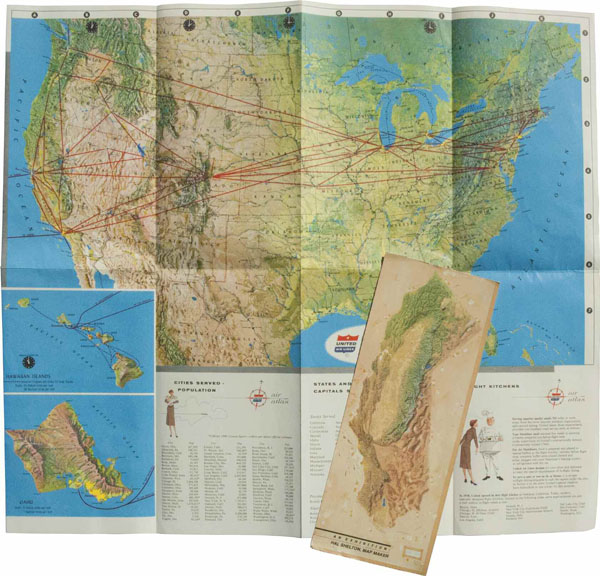

At the dawn of the Jet Age, Hal Shelton ’38 shook up the crusty world of cartography by making maps in which the colors matched the landscape.

Hal Shelton’38 changed the way we see the world, at least on paper. He brought artistry, color and a dash of common sense to the crusty field of cartography at the dawn of the Jet Age. Today, his maps are considered cartographic masterpieces.

An art major at Pomona, Shelton was introduced to cartography just after graduating when he went to work for the U.S. Geological Survey creating topographical maps in the field. Perplexed by some of the conventions of mapmaking, he became interested in the idea of “natural color”—making the area mapped look like it does to the eye.

“Up until Shelton came onto the scene, when you made maps, the color would represent, say, political areas [or] elevation …,” notes Tom Patterson, a National Park Service cartographer who has written extensively on Shelton’s career. “He really revolted against that idea because he felt that when people see these colors, they don’t think of elevation, they think of land cover and vegetation.”

The U.S.G.S. wasn’t interested at first, but soon enough the military was, and Shelton did some work for the Air Force during World War II. According to Shelton’s son Stony, his father’s big break came after the war when he met Elrey Jeppesen, a pilot who had started an aeronautical mapping business. Jeppesen saw the potential in Shelton’s approach, and soon the artist was making airline maps for the traveling public. The idea was that air travelers could look at maps that matched the terrain they saw out the window. “This was at the beginning of the jet era,” says Patterson. “People would get dressed up to go on an airline.”

If the natural color concept seems straightforward—forests are green, deserts are brown— the execution required patience, skill and considerable expense. Decades before satellite imagery was widely available, Jeppesen hired academic geographers to gather the data, which was etched into zinc plates about two to three feet in diameter. Working on an inch at a time, Shelton then painstakingly painted on the landscape features along with shaded relief to show elevation. His artistry yielded “realistic picture maps that astound the cartographic world,” as The New York Times gushed in 1954.

If the natural color concept seems straightforward—forests are green, deserts are brown— the execution required patience, skill and considerable expense. Decades before satellite imagery was widely available, Jeppesen hired academic geographers to gather the data, which was etched into zinc plates about two to three feet in diameter. Working on an inch at a time, Shelton then painstakingly painted on the landscape features along with shaded relief to show elevation. His artistry yielded “realistic picture maps that astound the cartographic world,” as The New York Times gushed in 1954.

The series of maps Shelton painted for Jeppesen came to be used not only by airlines but also in classrooms and by NASA. Even today, the work of Shelton, who died in 2004, remains relevant for cartographers. Raw satellite images hold too much “noise” and distraction, says Patterson, while Shelton’s less-literal technique brings out the most important features of the landscape to create an image that a casual reader can make sense of.

“He painted the entire world, he liked to say sometimes,” recalls Stony, who notes his father went on to create a series of well-known maps of Colorado ski areas and then left the cartographic work behind for a prolific career painting landscape scenes. “He created these, beautiful, beautiful maps that were just the landforms as they looked from space.”

And what became of those maps? The originals—valued at the time at more than $1 million—were donated to the Library of Congress in 1985 and exhibited with fanfare in 1997, when Shelton was flown to D.C. to take part in a showing timed to the maps division’s 100th anniversary. Years later, though, when Patterson came to see them at the maps division’s vast storage facility, Shelton’s creations led a more down-to-earth existence, tucked away among the “cabinets that just go on and on in the basement of the place.”

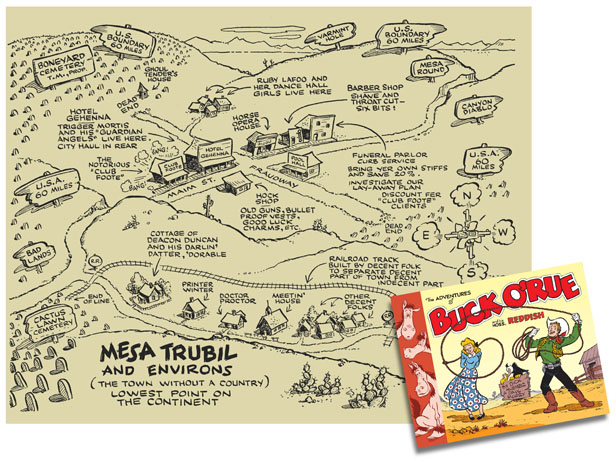

JEST OF THE WEST

Pulling together his father’s long-forgotten cowboy comic strips, Richard Huemer ’54 delved into an imaginary western world — and his dad’s psyche.

Just as Richard Huemer ’54 was settling into his first semester on Pomona’s leafy and idyllic campus, his father was bringing to life a very different realm in the newspaper comics.

Mesa Trubil, a weedy Western outpost so vile that the government wouldn’t claim it as part of the U.S.A., had only one hope in the form of hero on horseback Buck O’Rue. The noble and naïve cowboy tangled with malevolent Mayor Trigger Mortis and his henchmen, all the while dazzling love interest Dorable Duncan with his bravery.

The satirical strip was born of a career setback for Richard’s dad. Dick Huemer had been laid off from his job as a Disney writer, and that allowed him to pursue the project he had talked about for years. “He desperately needed something to do,” recalls Richard.

With Disney colleague Paul Murry on board to do the drawing, Dick Huemer got a small syndicate in Cleveland to promote the strip. But perhaps due to the syndicate’s limited reach, the strip didn’t go over big. And just as Buck hit the papers, Dick was back in the saddle at Disney, where his career later included co-writing Dumbo. By late 1952, the strip was kaput.

Dick Huemer died in 1979, but it wasn’t until Richard’s mother passed on 20 years later that the old comic came back into view as Richard sorted through his mother’s possessions. “The Buck O’Rue proofs were among the things she had saved all these years,” he says.

Next, Richard was contacted by a Swedish graduate student, Germund von Wowern, who was interested in the work of illustrator Murry (later one of the best-known illustrators of Mickey Mouse). The Swede wanted to know if Richard had any proofs of a strip called Buck O’Rue. Did he? Richard had nearly all of them.

Out of that came a 10-year collaboration through which Richard and von Wowern unearthed and filled in the missing pieces of the story of Buck O’Rue. Their efforts culminated with the publication last year of a 300-page book of old O’Rue strips accompanied by commentary.

Along the way, Richard gained insight into the era—and his own father. The strapping cowboy hero, in Richard’s eyes, epitomizes the America of the time. “There was a great deal of optimism,” he says. “And a feeling that we could do anything.”

Still, Richard’s adult eyes couldn’t ignore some things he missed in his youth. As Richard notes in the tome, Buck confronted a relentlessly foul cast of characters in Mesa Trubil, where political corruption was rife. Some of the strips featured a crazy old miner who carelessly tosses around his “schmatum bomb” that could destroy the world. All in all, the comic strip was rather bleak in its worldview, which Richard says seemed to reflect his father’s own outlook.

“He covered it with his jocularity. He liked humor and wordplay,” recalls Richard. “Inevitably, when you delve into the work of someone you know, you understand more about them.” So from those long-forgotten funnies, Richard wound up with a more rounded and complex picture of his dad. “That was a voyage of discovery for me, too,” he says.