At the Mayan ruin of Uxmal, Mexico, bat researcher Kirsten Bohn bends down beside a narrow crack in one of the ancient limestone walls. “Do you hear them?,” she asks. “The twittering? That’s our bats, and they’re singing.”

I lean in, too, and listen. It takes a moment for my ears to adjust to the bats’ soft sounds, and then the air seems to fill with their birdlike trills, chirps and buzzes.

The twittering calls are the songs of Nyctinomops laticaudatus, the broad-eared bat—one of several species of bats that scientists have identified as having tunes remarkably similar to those of birds. Like the songs of birds, bats’ melodies are composed of multiple syllables; they’re rhythmic and have patterns that are repeated.

And like birds, these bats sing not during the dark of night, but in the middle of the day, making it easy for us to see them, too.

Bohn, a behavioral ecologist at Florida International University in Miami, presses her face against the crack in the wall, and squints. “Well, hello there,” she says. I follow her example, and find myself eyeball-to-eyeball with one of the bats that’s sandwiched inside. He scuttles back, but his jaws chatter at me, “Zzzzzzzz.”

“He’s telling us to back off, to go away,” Bohn says, translating. “He wants to get back to his singing.”

That suits Bohn, who has traveled to Uxmal to record the broad-eared bats’ tunes for her study on the evolution and function of bat song—research that may help decode what the bats are saying to one another with their songs, and even teach us something about the origins of human language.

Not so long ago, most animal scientists and linguists regarded the sounds that animals and humans make as markedly different. Language was considered to be something only humans possessed; supposedly it appeared de novo instead of evolving via natural selection. And animals were regarded as incapable of intentionally uttering any sound. Songs, barks, roars, whistles: These were involuntary responses to some stimulus, just as your knee jerks when your doctor taps it. But since the 1990s, the notion of language as a uniquely human skill has fallen to the wayside as researchers in genetics, neurobiology and ethology discover numerous links between animal vocalizations and those of humans.

Take grammar and syntax, the rules that determine how words can be combined into phrases and sentences. Most linguists still insist that animal calls lack these fundamental elements of language. But primatologists studying the vocalizations of male Campbell’s monkeys in the forests of the Ivory Coast have found that they have rules (a “proto-syntax,” the scientists say) for adding extra sounds to their basic calls. We do this, too. For instance, we make a new word “henhouse,” when we add the word “house” to “hen.” The monkeys have three alarm calls: Hok for eagles, krak for leopards, and boom for disturbances such as a branch falling from a tree. By combining these three sounds the monkeys can form new messages. So, if a monkey wants another monkey to join him in a tree, he calls out “Boom boom!” They can also alter the meaning of their basic calls simply by adding the sound “oo” at the end, very much like we change the meanings of words by adding a suffix. Hok-oo alerts other monkeys to threats, such as an eagle perched in a tree, while krak-oo serves as a general warning.

Take grammar and syntax, the rules that determine how words can be combined into phrases and sentences. Most linguists still insist that animal calls lack these fundamental elements of language. But primatologists studying the vocalizations of male Campbell’s monkeys in the forests of the Ivory Coast have found that they have rules (a “proto-syntax,” the scientists say) for adding extra sounds to their basic calls. We do this, too. For instance, we make a new word “henhouse,” when we add the word “house” to “hen.” The monkeys have three alarm calls: Hok for eagles, krak for leopards, and boom for disturbances such as a branch falling from a tree. By combining these three sounds the monkeys can form new messages. So, if a monkey wants another monkey to join him in a tree, he calls out “Boom boom!” They can also alter the meaning of their basic calls simply by adding the sound “oo” at the end, very much like we change the meanings of words by adding a suffix. Hok-oo alerts other monkeys to threats, such as an eagle perched in a tree, while krak-oo serves as a general warning.

Scientists have found—and decoded—warning calls in several species, including other primates, prairie dogs, meerkats and chickens. All convey a remarkable amount of information to their fellows. The high-pitched barks of prairie dogs may sound alike to us, but via some variation in tone and frequency he or she can shout out a surprisingly precise alert: “Look out! Tall human in blue, running.” Or, “Look out! Short human in yellow, walking!”

Many animals use their calls to announce that they’ve found food, or are seeking mates, or want others to stay out of their territories. Ornithologists studying birdsong often joke that all the musical notes are really about nothing more than sex, violence, food and alarms. Yet we’ve learned the most about the biological roots of language via songbirds because they learn their songs just as we learn to speak: by listening to others. The skill is called vocal learning, and it’s what makes it possible for mockingbirds to mimic a meowing cat or a melodious sparrow, and for pet parrots to imitate their owners. Our dogs and cats, alas, will never say “I love you, too” or “Good night, sweetheart, good night,” no matter how many times we repeat the phrases to them, because they lack both the neural and physical anatomy to hear a sound and then repeat it. Chimpanzees and bonobos, our closest relatives, cannot do this either, even if they are raised from infancy in our homes.

Via vocal learning, some species of songbirds acquire more than 100 tunes. And via vocal learning, the chicks of a small parrot, the green-rumped parrotlet, obtain their “signature contact calls”—sounds that serve the same function as our names.

A few years ago, I joined ornithologist Karl Berg from the University of Texas in Brownsville at his field site in Venezuela where he studies the parrotlets’ peeping calls. Although the peeps sound simple to our ears, Berg explained, they are actually complex, composed of discrete sequences and phrases. A male parrotlet returning to his mate at their nest, a hollow in a fence post, makes a series of these peeps. “He calls his name and the name of his mate,” Berg told me, “and then he’s saying something else. And it’s probably more than just, ‘Hi Honey, I’m home.’” Because the female lays eggs throughout the long nesting season, the pair frequently copulates. And so, Berg suspects that a male on his way home after laboring to fill his crop with seeds for his mate and their chicks, is apt to call out, “I’ve got food, but I want sex first.” His mate, on the other hand, is likely hungry and tired from tending their chicks. She may respond, “No, I want to eat first; we’ll have sex later.” “There’s some negotiating, some conversation between them,” Berg said, “meaning that what one says influences what the other says next.”

Berg discovered that parrotlets have names by collecting thousands of the birds’ peeps, then converting them to spectrograms, which he subsequently analyzed for subtle similarities and differences via a specialized computer program. And how does a young parrotlet get his or her name? “We think their parents name them,” Berg said—which would make parrots the first animals, aside from humans, known to assign names to their offspring.

Berg discovered that parrotlets have names by collecting thousands of the birds’ peeps, then converting them to spectrograms, which he subsequently analyzed for subtle similarities and differences via a specialized computer program. And how does a young parrotlet get his or her name? “We think their parents name them,” Berg said—which would make parrots the first animals, aside from humans, known to assign names to their offspring.

Parrotlets aren’t the only animals that have names (or to be scientifically accurate, signature contact calls). Scientists have discovered that dolphins, which are also vocal-learners, have these calls, although these seem to be innate; the mothers aren’t naming their calves. And some species of bats have names, which they include when singing, and in other social situations.

Bats sing, for the same reason birds do: to attract mates and to defend territories. They’re not negotiating or conversing, but their lovelorn ditties are plenty informative nonetheless. After analyzing 3,000 recordings of male European Pipistrellus nathusii bats, for instance, a team of Czech researchers reported that the songs always begin with a phrase (which the scientists termed motif A) announcing the bat’s species. Next comes the vocal signature (motifs B and C), information about the bat’s population (motif D), and an explanation about where to land (motif E).

“Hence, translated into human words, the message ‘ABCED’ could be approximately: (A) ‘Pay attention: I am a P.nathusii, (B,C) specifically male 17b, (E) land here, (D) we share a common social identity and common communication pool,’” the researchers wrote in their report.

Bohn suspects that the tunes of her bats at Uxmal convey the same type of information. “The guys are competing for females with their songs,” she says, “so they can’t afford to stop singing.” She doesn’t yet know what the females listen for in the voice of a N.laticaudatus, but expects that something in a male’s intonation or his song’s beat gives her clues about his suitability as a mate.

But her focus is on another question: Are these bats long-term vocal learners, as are humans and some species of birds, such as parrots? “If they are,” she explains, “then they might be a good model for studying the origins of human speech”—which would make bats the first mammal ever used for such research.

Bohn had earlier recorded some of the bats’ songs, and digitally altered these so that they sounded like the refrains of different bats—strangers. At the wall, she attaches a pair of microphones and a single speaker to a tripod, and points the equipment at the fissure, where the bats sing. Pushing a button on her laptop, she broadcasts the remixed bat songs to the tiny troubadours, who respond with even louder twitters, trills, and buzzes. Bohn watches their responses as they’re converted into sonograms that stream across her laptop’s screen like seismic pulses. These are territorial buzzes and contact calls, Bohn explains. “They know there’s an intruder.” She’s silent for a moment, and then beams. “Yes! One of the guys is trying to match the intruder’s call. He doesn’t have it exactly right, but he’s close—he’s so close, and it’s hard.”

But there it was: the first bit of evidence that bats are life-long vocal learners. Just like us.

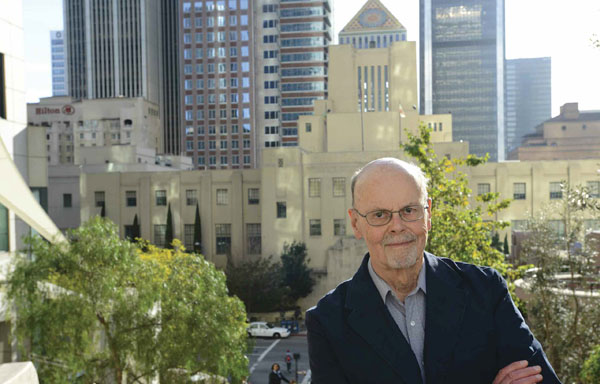

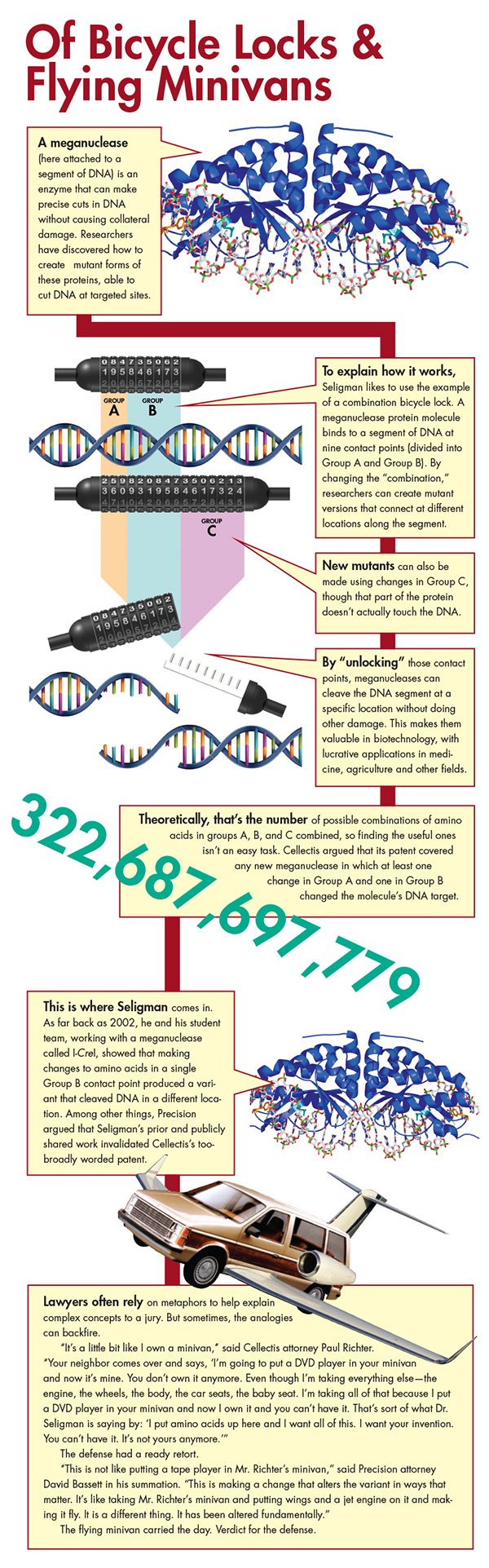

Expert witnesses at contentious trials can expect to be challenged, even discredited. But when he took the stand last year in a complex biotech patent case, Pomona Biology Professor Lenny Seligman never anticipated that his groundbreaking work at Pomona would be relegated to the “ash heap of failure.”

Expert witnesses at contentious trials can expect to be challenged, even discredited. But when he took the stand last year in a complex biotech patent case, Pomona Biology Professor Lenny Seligman never anticipated that his groundbreaking work at Pomona would be relegated to the “ash heap of failure.”

Lunch was supposed to be casual. Mikey Dickerson ’01 was in Chicago catching up with Dan Wagner, a friend who’d been in the trenches with him on Barack Obama’s campaign for the presidency in 2012. Wagner had since gone on to found a company, Civis Analytics; Dickerson was a site reliability engineer at Google, one of the people who make sure that the search engine never, ever breaks down.

Lunch was supposed to be casual. Mikey Dickerson ’01 was in Chicago catching up with Dan Wagner, a friend who’d been in the trenches with him on Barack Obama’s campaign for the presidency in 2012. Wagner had since gone on to found a company, Civis Analytics; Dickerson was a site reliability engineer at Google, one of the people who make sure that the search engine never, ever breaks down. With 12 days left before the deadline, Dickerson was ready to go home. He gave a speech listing the five mission-critical things remaining, and attempted to flee back to California. But the bosses panicked. The Ad Hoc guys can’t go home, they said. They gave him the service-to-your-country pitch. They begged. So Dickerson agreed to stay through to the end—with some conditions. He got to set the specific technical goals for what his team and the rest of the government coders would do. And he got to hire whomever he wanted, without arguing the point. He wanted to be able to trust the new team members, so he chose them himself. Eventually a rotating team of Google site reliability engineers started coming through to keep the project on track.

With 12 days left before the deadline, Dickerson was ready to go home. He gave a speech listing the five mission-critical things remaining, and attempted to flee back to California. But the bosses panicked. The Ad Hoc guys can’t go home, they said. They gave him the service-to-your-country pitch. They begged. So Dickerson agreed to stay through to the end—with some conditions. He got to set the specific technical goals for what his team and the rest of the government coders would do. And he got to hire whomever he wanted, without arguing the point. He wanted to be able to trust the new team members, so he chose them himself. Eventually a rotating team of Google site reliability engineers started coming through to keep the project on track. A geek hunched over a laptop tapping frantically at the keyboard, neon-bright lines of green code sliding up the screen—the programmer at work is now a familiar staple of popular entertainment. The clipped shorthand and digits of programming languages are familiar even to civilians, if only as runic incantations charged with world-changing power. Computing has transformed all our lives, but the processes and cultures that produce software remain largely opaque, alien, unknown. This is certainly true within my own professional community of fiction writers—whenever I tell one of my fellow authors that I supported myself through the writing of my first novel by working as a programmer and a computer consultant, I evoke a response that mixes bemusement, bafflement and a touch of awe, as if I’d just said that I could levitate. Most of the artists I know—painters, film-makers, actors, poets —seem to regard programming as an esoteric scientific discipline; they are keenly aware of its cultural mystique, envious of its potential profitability, and eager to extract metaphors, imagery and dramatic possibility from its history, but coding may as well be nuclear physics as far as relevance to their own daily practice is concerned.

A geek hunched over a laptop tapping frantically at the keyboard, neon-bright lines of green code sliding up the screen—the programmer at work is now a familiar staple of popular entertainment. The clipped shorthand and digits of programming languages are familiar even to civilians, if only as runic incantations charged with world-changing power. Computing has transformed all our lives, but the processes and cultures that produce software remain largely opaque, alien, unknown. This is certainly true within my own professional community of fiction writers—whenever I tell one of my fellow authors that I supported myself through the writing of my first novel by working as a programmer and a computer consultant, I evoke a response that mixes bemusement, bafflement and a touch of awe, as if I’d just said that I could levitate. Most of the artists I know—painters, film-makers, actors, poets —seem to regard programming as an esoteric scientific discipline; they are keenly aware of its cultural mystique, envious of its potential profitability, and eager to extract metaphors, imagery and dramatic possibility from its history, but coding may as well be nuclear physics as far as relevance to their own daily practice is concerned. A poet, however, might wonder why Lampson would place poetry making on the same spectrum of complexity as aircraft design, how the two disciplines—besides being ‘creative’—are in any way similar. After all, if Lampson’s intent is to point towards the future reduction of technological overhead and the democratization of programming, there are plenty of other technical and scientific fields in which the employment of pencil and paper by individuals might produce substantial results. Architecture, perhaps, or carpentry, or mathematics. One thinks of Einstein in the patent office at Bern. But even the title of Lampson’s essay hints at a desire for kinship with writers, an identification that aligns what programmers and authors do and makes them—somehow, eventually—the same.

A poet, however, might wonder why Lampson would place poetry making on the same spectrum of complexity as aircraft design, how the two disciplines—besides being ‘creative’—are in any way similar. After all, if Lampson’s intent is to point towards the future reduction of technological overhead and the democratization of programming, there are plenty of other technical and scientific fields in which the employment of pencil and paper by individuals might produce substantial results. Architecture, perhaps, or carpentry, or mathematics. One thinks of Einstein in the patent office at Bern. But even the title of Lampson’s essay hints at a desire for kinship with writers, an identification that aligns what programmers and authors do and makes them—somehow, eventually—the same.

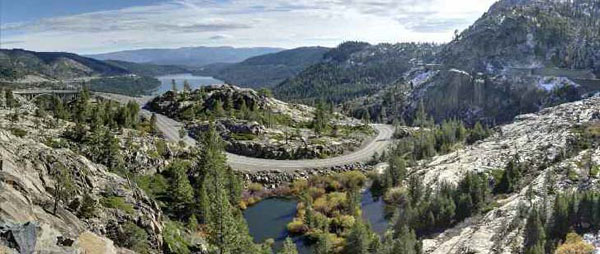

As it is, things have worked out nicely. California’s climactic geography came last, a necessary if unanticipated coda to what is often called the American experience. Knowing the end of the story—so far— makes it easy to grasp how incomplete this country would have felt without California, the volatile edge, it seems, of all our national imaginings. For much of the way westward, the story was about settling down, finding a homestead and improving it. But California was never really about settling down. Its very geology is transient. This is where you file a claim on the future and hope that events don’t overtake you.

As it is, things have worked out nicely. California’s climactic geography came last, a necessary if unanticipated coda to what is often called the American experience. Knowing the end of the story—so far— makes it easy to grasp how incomplete this country would have felt without California, the volatile edge, it seems, of all our national imaginings. For much of the way westward, the story was about settling down, finding a homestead and improving it. But California was never really about settling down. Its very geology is transient. This is where you file a claim on the future and hope that events don’t overtake you.

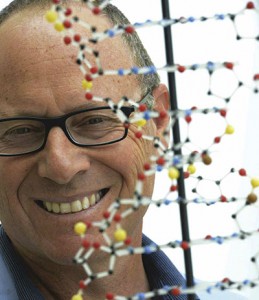

Professor Garza proudly points to several of his own success stories. One of them is Dr. Gerardo Lopez-Mena ’04 (pictured), the son of Mexican immigrants, born and raised in the blue-collar community of El Monte. Lopez-Mena—who uses his dual surname from his father, a custodian, and his mother, a homemaker—got a generous college scholarship and graduated with a degree in chemistry. But he couldn’t have made it without mentors, he says, including Prof. Garza who encouraged him to do research and made him co-author of a serious scientific paper published in the journal Chemical Physics Letters.

Professor Garza proudly points to several of his own success stories. One of them is Dr. Gerardo Lopez-Mena ’04 (pictured), the son of Mexican immigrants, born and raised in the blue-collar community of El Monte. Lopez-Mena—who uses his dual surname from his father, a custodian, and his mother, a homemaker—got a generous college scholarship and graduated with a degree in chemistry. But he couldn’t have made it without mentors, he says, including Prof. Garza who encouraged him to do research and made him co-author of a serious scientific paper published in the journal Chemical Physics Letters.

THOUGH CORNELL GRADUATED a century ago, his plantings remain a conspicuous presence, and the late landscaping genius is still central to the story of Pomona’s intriguing mix of trees. Cornell was fascinated with foliage from his first semester at Pomona, when he took a botany course with charismatic Biology Professor Charles Fuller Baker. Soon, Cornell had a business venture selling saplings grown from Mexican avocado seeds, and the profits enabled him to go on to Harvard and earn his master’s in landscape architecture. Cornell found his way back to Southern California, and Pomona quickly hired him as the campus’ landscape architect, a role he would hold for four decades.

THOUGH CORNELL GRADUATED a century ago, his plantings remain a conspicuous presence, and the late landscaping genius is still central to the story of Pomona’s intriguing mix of trees. Cornell was fascinated with foliage from his first semester at Pomona, when he took a botany course with charismatic Biology Professor Charles Fuller Baker. Soon, Cornell had a business venture selling saplings grown from Mexican avocado seeds, and the profits enabled him to go on to Harvard and earn his master’s in landscape architecture. Cornell found his way back to Southern California, and Pomona quickly hired him as the campus’ landscape architect, a role he would hold for four decades.