There are trophies. big, heavy, metal ones. And there are checks. Those are big, too, with lots of zeroes.

The image of videogaming as a solitary pursuit of adolescents is becoming a relic, partly because of technology that has turned gaming into a shared experience with huge audiences and partly because of — what else? — money, and the opportunity to make plenty of it.

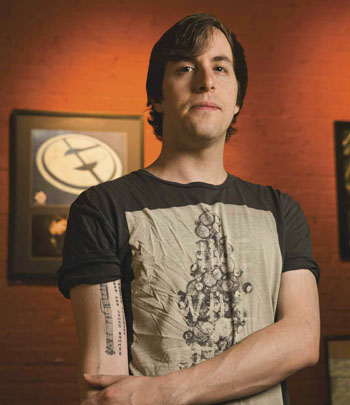

Alexander Garfield ’07 is a key figure in the burgeoning world know as eSports, but not because he is a player. The slender, erudite 28-year-old with tattoos written in Latin and Greek is the pioneering owner of Evil Geniuses, best described as a group of professional sports teams, a media company and a marketing venture rolled all into one.

It is as if Garfield runs both the New York Yankees and Manchester United of the video gaming world.

His Evil Geniuses teams are the most famous, but in August, a Swedish team playing for him under the new name Alliance competed in The International 3, a tournament held in Seattle for DOTA 2, a multi-player online battle game. The competition was waged in the elegant Benaroya Hall, home to the Seattle Symphony Orchestra, and it was a sellout.

Garfield’s team, led by 25-year-old Jonathan “Loda” Berg, finished first and took home a stunning $1.4 million in prize money, a record for a video-game competition.

“Is it weird?” Garfield asks, sitting in the company’s loft-style offices in San Francisco’s SoMa neighborhood, surrounded by video monitors, keyboards, samples of sponsors’ products and a small studio where gamers and commentators create video content for the web. Well, yes, it is weird to many, this unfamiliar world of professionalized video gaming. But it is a scene that is growing rapidly, a fact noted by both

The New York Times and Forbes.com, which last year named Garfield to its “30 under 30” list for games and apps.

The grandest coming-of-age moment for eSports yet came in October, when the 2013 world championship of the game League of Legends sold out Staples Center, home to the Los Angeles Lakers. Fans paid $45 to $100 to watch teams compete for the $1 million prize, won by a South Korean team in a setting that looked like a mix of a concert, a sporting event and a light show. More than 10,000 watched the competition on huge video screens. More than a million more viewed it online.

To anyone who thinks it is impossible to earn a living playing a kid’s game, consider the early days of baseball, when players took jobs in the off season to make ends meet. Last year, the average Major League Baseball salary was north of $3.2 million. Some pro video gamers already earn six figures, and Berg, who took a share of the $1.4 million prize, will surpass $300,000 this year.

The logo for the largest U.S. eSports organization, Major League Gaming—with the letters MLG and a game controller in white against a blue-and-red background—looks suspiciously like the MLB logo. Could video gaming possibly have the potential of traditional pro sports?

“I always say, I’m a sociologist, not a futurologist,” says T.L. Taylor, an associate professor of comparative media studies at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and expert on eSports. “One thing we can see really clearly right now is the exponential growth of the audience, and the growth of this as a spectator event.

“Alex is an interesting guy because he has been in the scene quite a while. He’s been around a long time and there have been ups and downs and bubbles and bursts, but Evil Geniuses has handled it all.”

GARFIELD IS AN ACCIDENTAL ENTREPRENEUR. Growing up in suburban Philadelphia, he trained as a classical violinist and was a huge fan of traditional professional sports. Garfield’s slight build limited him to racquet sports, but a video game called Counter-Strike became his competitive outlet. He fell into the role of impresario as a student at Pomona College, when a team of five Canadian friends wanted to go to Dallas for a tournament in 2005 but didn’t have the money. Garfield borrowed $1,000 from his mother to front them, the team finished second and he was on his way. Soon, he was courting sponsors and traveling to tournaments in Italy and Singapore.

GARFIELD IS AN ACCIDENTAL ENTREPRENEUR. Growing up in suburban Philadelphia, he trained as a classical violinist and was a huge fan of traditional professional sports. Garfield’s slight build limited him to racquet sports, but a video game called Counter-Strike became his competitive outlet. He fell into the role of impresario as a student at Pomona College, when a team of five Canadian friends wanted to go to Dallas for a tournament in 2005 but didn’t have the money. Garfield borrowed $1,000 from his mother to front them, the team finished second and he was on his way. Soon, he was courting sponsors and traveling to tournaments in Italy and Singapore.

If anyone finds the idea of watching someone else play video games odd, or the concept that a keyboard and a mouse could be the tools of a pro sport, Garfield simply shrugs.

“It varies culture by culture, right? In Eastern Europe, people pack stadiums to watch chess,” he says. “I’m not really concerned about whether this is a sport or a competitive activity, personally.”

With no training in business, Garfield nonetheless built a company with annual revenues he describes as being in the range of several million. (Because it is a privately held company with Garfield the majority owner, Evil Geniuses is not required to make financial data public.)

“My business training is I read The Lean Startup. That’s it,” he says, adding that he only read it recently.

“There were moments I really wished I’d taken some sort of economics course. Because I was like the kid at Pomona who, I think when my friends would say they were going to take econ, I would say, ‘How intact is your soul?’ Which in retrospect is such a ridiculous thing to say. I could really have benefited from micro or macro econ or business management.”

Evil Geniuses now has 15 fulltime employees and about 45 players under contract, with the gamers’ base salaries ranging from about $15,000 to $150,000 year and prize money shared with the company depending on the player’s contract, Garfield says. Under the Evil Geniuses banner, his teams compete in games ranging from StarCraft 2 to World of Warcraft. Sponsors and advertising are the driving forces, and Garfield emerged as a leader in the young industry partly because he was not only able to choose and manage top players, but also able to court sponsors with a sophisticated media presence and the analytics to prove the value of investing in what to some companies was still an unfamiliar world. The Evil Geniuses offices are stocked with cans of their top sponsor’s Monster Energy drinks, their own Evil Geniuses logo merchandise and computer gear from such sponsors as Intel, one of their first. If some of this seems reminiscent of the X Games, that’s not far off base.

“If you look at some of the industries that have gone from underground to mainstream in recent years, you think of action sports, you think of the DJ culture, you think of poker,” Garfield says. “Major media companies and major consumer brands have played a huge role. For the most part, it’s very similar.”

Garfield and Taylor, the MIT professor, note that the other development that has fueled the growth of eSports is streaming video, which not only allows people to watch live tournaments online or a favorite player’s practice sessions, but it also provides the marketing data.

Take a look at the web site Twitch.TV, a Bay Area startup drawing 45 million unique visitors a month that recently received $20 million in venture capital, and you might see more than 100,000 people viewing League of Legends content, another 90,000 watching DOTA 2, and more than 15,000 each looking at World of Warcraft and StarCraft II, all on a weekday afternoon. Garfield points to a practice session being streamed by Conan Liu, an Evil Geniuses player and pre-med student at UC Berkeley who goes by the alias “Suppy.” Liu plans to take a year off from his studies to pursue gaming, and the screen shows 500 people watching him practice.

“My job would be much more difficult today if there weren’t technology platforms that allow my players to create content and have very trackable analytics, like, ‘This is my fan base and I can prove it,’” Garfield says.

Players also prove their marketability on such sites as Facebook and Twitter. Stephen Ellis, a 22-year-old Scottish League of Legends player for Evil Geniuses who is also known as “Snoopeh,” has more than 147,000 “Likes” on Facebook and more than 119,000 followers on Twitter. On a recent U.S. trip to provide commentary on the League of Legends championships and record content at the Evil Geniuses studio, he had a “fan meet” at USC, and some 100 students appeared to greet him.

To support some of his players in the Bay Area, Garfield established a “team house” in Alameda, across the San Francisco Bay from the company offices. There, a group of young men live and practice together, with housekeeping help. “The notion that some players live an unhealthy lifestyle is still there, that guys don’t take care of themselves or drop out of high school,” Garfield says. “But there is generally, with our players, a very balanced approach. They play games eight to 10 hours a day, but they go to the gym together, they go to bars together, they hang out with girls together.” Garfield is willing to crack down when he has to. When one of his players used a racial epithet online last year, Garfield dismissed him, and wrote a lengthy blog post explaining the move.

“Alex is one of the team owners who has taken a pretty firm stand on trying to regulate bad player behavior,” says Taylor, the MIT professor and author of the book Raising the Stakes: E-sports and the Professionalization of Computer Gaming.

Crude language and sexism also are sometimes issues in an arena populated largely by 18-to-30-year-old males.

“Evil Geniuses has released people from contracts for bad behavior, and that’s a brave thing to do,” Taylor says.

FOR ALL THIS, THE COMPANY VISIONARY is a bit removed. “I haven’t played games for a very long time, actually,” Garfield says. “There are tons of people, including me, who haven’t played StarCraft in, like, two years, but still really enjoy watching it.”

Garfield watches his own players, certainly. But for him, gaming became a business venture, and one that the former sociology major with minors in Africana studies and classics says he feels conflicted about at times. He is interested in music, writing songs and creating a few tracks in a genre he describes as “electroacoustic to strictly acoustic.” And concerns about the issues of race and privilege he learned about in college still tug at him. Garfield enjoys a few accoutrements of his success, but notes “I’m not a zillionaire.”

“My apartment is cool. My job is cool,” he says, dressed in jeans, a black T-shirt and high-top sneakers, his usual work attire. “Don’t get me wrong, getting a cut of the prize money for winning a tournament for $1.4 million is nice. But I think eventually I will be involved in this less, just because for me, even though this is a really interesting experience, as recently as two years ago, I was very frustrated.”

Instead of working to promote causes he cared about or making music, he was becoming well-known in a world he never meant to join. Then he had an epiphany.

“It was only at a certain point that I realized the skill set that I was developing by basically running a startup with no money in an industry that has no boundaries, no foundation and no rulebook,” Garfield says. “Then I was like, OK, this makes sense now, because I have all these skills I can use in my music career, that I could use for private projects in social justice later in life.”

In the meantime, he wrestles with how to portray himself. Gamer dude? Tech entrepreneur? Musician? Aspiring activist?

“I’ve just come to lying to people about what I do on airplanes,” he says. “I say, ‘Well, I do x, y and z.’ So the next question is, ‘Oh, you make the games?’ I say no. ‘So, OK, you test the games?’ I just end up saying ‘yeah.’ But actually it’s really simple. It’s a sports team.”