THE STORY WAS in the works for weeks. The Los Angeles Times was preparing a front-page profile of California’s first Muslim judge, Halim Dhanidina ’94. And the paper was carefully vetting its subject, checking his background as the son of Indian immigrants, interviewing former colleagues in the D.A.’s office, and watching him preside over criminal proceedings at the L.A. County Superior Court in Long Beach.

After three months, the judge remembers getting a call from the reporter with some bad news. Editors were considering killing the story. The reason: “We’re not finding anything controversial.”

In the end, the paper ran the article after all. As far as the judge was concerned, the only thing controversial was the headline, which he called “almost inflammatory.” It read: Faith Leads State’s First Islamic Judge to the Bench.

Though modified online, the printed headline played into the worst preconceptions about Muslims that Dhanidina had been battling since his student days at Pomona College. He thought the wording portrayed him as a zealot who would impose sharia law from the bench. Which is exactly what anti-Muslim critics warned against, at websites with names like Jihad Watch and Creeping Sharia. Some wondered whether a Muslim judge in “Caliph-ornia” could be impartial when sentencing “jihadis, honor killers and those who assault non-believers.”

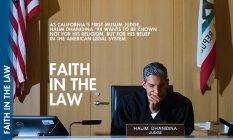

“If you’re going to ask me about sharia law, you’re going to be misled, because I don’t know anything about it,” said the judge during an interview at his tidy courthouse office, decorated with cheerful artwork from his two children. “I’m an American that works in the American legal system. You can ask me anything about that and I’ll give you a better answer.”

Dhanidina, who holds a law degree from UCLA, has been answering questions about Islam and the law since that day in 2012 when Gov. Jerry Brown announced his ascension to the bench as a milestone for Muslims. Dhanidina, just 39 at the time, says his religion had never been a defining issue in his career until then. During his 14 years as a deputy district attorney in Los Angeles, prosecuting gang-related murder cases, many colleagues didn’t even know he was a Muslim.

Though he felt awkward at first, Dhanidina now embraces his high-profile role as a public figure from his community. Yes, he worries that carrying a religious banner may detract from his accomplishments. He wants to be recognized for his public work, not his private beliefs. Yet he believes the focus on his faith serves a purpose, because it makes him “a symbol of inclusion.”

“Part of the value of diversity is for people to know about it,” says the judge, who often speaks at schools and on professional panels. “The role of Muslims in American society right now is very tenuous. There are efforts to make Muslims feel they’re not welcome in the U.S., that they don’t belong here, that they should not be allowed to come, to stay, to participate in institutions.”

For fellow Muslims, seeing his success proves the opposite: “There is a place for you, too.”

The judge also believes that his public visibility can help change perceptions among non-Muslims, many of whom get their impressions about Islam from the media or the Internet. It’s easy to believe in stereotypes about a group, he notes, when you don’t personally know any of its members. “That’s why Muslims in the public eye need to be open,” he says, “because it helps to demystify this idea of what ‘these people’ are like.”

Of course, Dhanidina’s work as a judge is an open book. His court is open to the public; his rulings are public record. That helps dispel any suspicions that he may be somehow secretly imposing his personal ideology on the court.

“People think that if you’re a Muslim, you believe in chopping off heads and oppressing women,” he says. “But it’s very easy to say what a Muslim would be like as a judge if there aren’t any Muslim judges. Well, now there is one here in California. So if anybody wants to know what a Muslim would do as a judge in an American court, they would come to Department Eight of the Long Beach Superior Court and see for themselves.”

PRESIDING IN COURT one recent afternoon, Judge Dhanidina displayed a carefully studied judicial demeanor. He begins every day with a formal flag salute, “in respect of the rights we enjoy.” On the bench, he is disciplined, efficient and formal, almost courtly. With defendants, he is respectful and encouraging, telling one who presented a good probation report to “keep up the good work.” And throughout, he maintains perfect posture in a robe that looks tailored to his fit, six-foot-one frame.

His goal is to run a courtroom “with dignity and decorum,” he says, where justice prevails and everybody feels they are treated fairly. “They would never know they were in the Muslim guy’s court,” he adds, “unless somebody told them.”

Outside the hallowed halls, the judge lets his hair down. An easy smile softens the slightly severe look of his gray goatee, precisely manicured along the ridge of his chin. He is friendly and chatty with a group of students from his daughter’s elementary school, visiting on a field trip. “You were awesome in the musical,” he says to one. “Are you playing softball in the fall?” he asks another.

“I want the young people to feel I’m just a regular guy,” says the judge, because it sends a message that they can make it too.

In many ways, he is a regular guy. Softball coach, loyal Cubs fan, aficionado of Spanish rock, dad who drives his kids to school. But Dhanidina also is driven to excel, to be the best in whatever he does. He attributes his competitive streak to his immigrant parents, who always strived to succeed.

“When you meet Halim, or appear before him, what strikes you is not his faith, but that he’s such a smart, hardworking judge,” says Long Beach Supervising Judge Michael Vicencia. “So whatever kind of preconceived notions people may have had, the second they meet him all of that goes away because you’re so impressed by what a good judge he is.”

So far, nobody has formally complained about Dhanidina’s performance, says Vicencia, who fields complaints against judges in Long Beach. And nobody has raised concerns about his religion either.

At his swearing-in, Dhanidina assiduously sidestepped a potential public controversy, avoiding the brouhaha that erupted in Brooklyn last year when a fellow Muslim judge swore her oath on the Quran. Instead, he chose not to swear on any holy book, dismissing the issue as irrelevant.

For a judge with such an even temper, though, it’s surprising to hear Dhanidina admit that he is “certainly sensitive to slights.” When the governor’s office received hate mail in response to his appointment, he acknowledges matter-of-factly that “it hurt my feelings.”

Dhanidina, who won election to his first full term in 2014, doesn’t consider himself a victim who harbors grievances. But he has experienced his share of prejudice in the past. Like the dinner-party guest openly expressing anti-Muslim sentiments. Or the thoughtless coworker using the pejorative term “towelhead.”

Then there was the defense attorney who once tried to save a murderer from the death penalty with a thinly disguised appeal to religious prejudice. Dhanidina was the prosecutor at the time and had won convictions for the double homicide. In the penalty phase, the opposing lawyer argued that the jury should show mercy consistent with “our” Judeo-Christian values, not like those of the prosecutor who follows “different” traditions.

The strategy failed, but Dhanidina never forgave the judge in that 2008 case for not stepping in to stop it. “The argument itself didn’t hurt me,” he says, “but the fact that the judge did not officially stamp it as inappropriate, that stung more.” Later, when he faced the same lawyer again in a different case with a different judge, Dhanidina made a preemptive strike, asking the court to prohibit him from making the same offensive argument. The judge agreed, admonishing the defense lawyer, “If this is not an appeal to prejudice, explain to me what it is.”

“That was a very gratifying moment for me,” concludes Dhanidina, “because OK, somebody else has acknowledged that this isn’t right.”

IT’S OBVIOUS, SAYS DHANIDINA that animosity toward Muslims has worsened in the quarter century since he worked for better interfaith relations as a student at Pomona. The terrorist attacks of 911 and subsequent Middle East wars have stoked public fears about the perceived connection between Islam and violence. The judge blames both sides: the terrorists, for cloaking themselves in a distorted reading of Islam, and self-serving politicians, for exploiting the violence to scapegoat an entire religion.

“It’s baffling to Muslim people like myself, and millions around the world, who have never seen any kind of doctrinal link between violence and their religion,” he says. “We don’t understand how other people can make that connection.”

Less than a month after the interview, the issue of Islam and violence was back in the news in a shocking way. In the worst mass shooting in modern U.S. history, a gunman vowing allegiance to Islamic terrorist groups massacred 49 people at a nightclub in Orlando, Florida. Since many of the victims were gay, the case also refocused attention on the treatment of homosexuals in Islamic countries, including a handful where homosexuality is punishable by death.

The issue is not new to Dhanidina. Even fellow Muslims have asked him how he can reconcile legal issues such as gay marriage with traditional Islam. Asked another way, can a Muslim judge be fair to homosexuals?

Coincidentally, Dhanidina had already addressed that question in a controversial case watched closely by gay rights advocates. The case involved a police sting that led to charges against a 50-year-old man for lewd conduct and indecent exposure in a public park. In a blistering, 17-page ruling handed down in April, Dhanidina blasted the Long Beach Police Department and local prosecutors for what he called an “arbitrary enforcement of the law” that specifically targeted gay men. The judge found that police “harbored animus toward homosexuals” and that the prosecution was fueled by “the rhetoric of homophobia.”

“When I think of what values are important in a society, equality is right at the top,” the judge says. “That’s probably because I’ve never been in a majority. Of anything. Anywhere.”

DHANIDINA BELONGS TO the Ismaili religious community, a historically persecuted offshoot of the Shia branch of Islam, known for its modern, progressive views. “We don’t believe in the religious superiority of one group over another,” says Dhanidina, whose Thailand-born wife was raised Roman Catholic. “We believe that different religions are just different paths to the same place.”

His ethnic heritage traces to the Gujarati people of western India, an illustrious community that also includes independence leader Mahatma Gandhi, British actor Ben Kingsley, and Queen lead vocalist Freddie Mercury. His grandparents were born in Tanzania, part of the Indian diaspora in East Africa during British colonial rule. His parents, Lutaf and Mali, met at a Tanzanian teachers college. The couple came to the United States in the early 1960s when his father got a scholarship to Northwestern University. Eventually, most of the extended family came here too.

Born in 1972, Dhanidina was raised with his older brother in the Chicago suburb of Evanston, Illinois, where Northwestern is located. At home, language and food were a natural blend of Asian, African and Anglo-American influences. (“Growing up, I didn’t even know which word came from which language.”) He graduated from Evanston Township High School in 1990, still using the first name Al-Halim.

He arrived as a freshman at Pomona at the height of the First Gulf War, finding himself peppered with questions about Islam, “as if you were the spokesman for everybody.” At the time, he was one of literally a handful of Muslim students on all five Claremont campuses combined. “We still managed to find each other to start the Muslim Students Association,” he recalls. Initially, the group rallied around a campaign to keep dining halls open later during Ramadan, which requires fasting until after sunset. From that victory, the goals evolved, stressing education to combat stereotypes and promote better understanding.

Dhanidina, an aspiring diplomat who got a degree in international relations, knew he had come to the right school. Pomona’s diversity is what drew him here in the first place.

“I think I would not be the person I am today if I had not gone to Pomona,” says the judge, who still maintains strong friendships with a multicultural group of his freshman hall mates. “Everyone is encouraged to think big about the ways they want to make the world a better place. And I really bought into that.”

—Photos by Lori Shepler

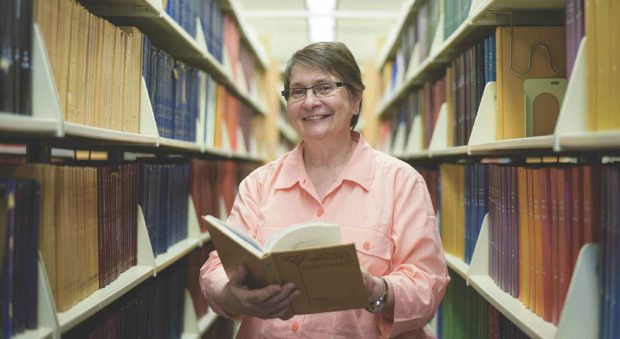

There’s another Oxtoby who has had a Pomona presence for the last 13-plus years. Claire Oxtoby has a view of the College and a college president’s role unique to that of a life partner. But she has been a participant at Pomona, not just an observer.

There’s another Oxtoby who has had a Pomona presence for the last 13-plus years. Claire Oxtoby has a view of the College and a college president’s role unique to that of a life partner. But she has been a participant at Pomona, not just an observer.

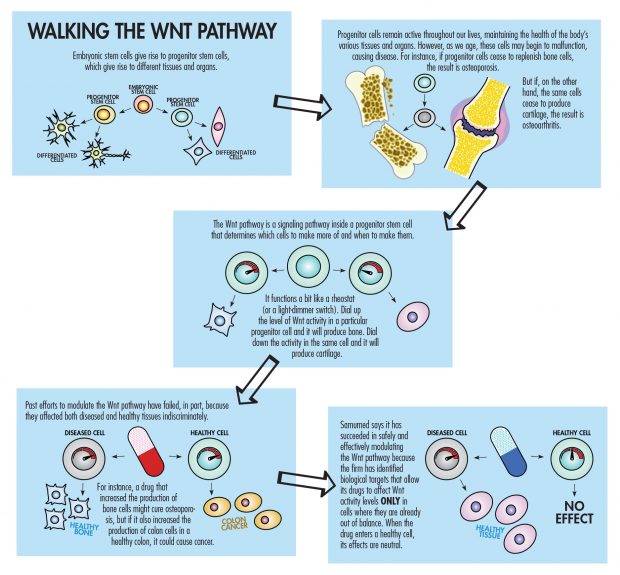

“After all is said and done, if we have just one approval, then we have failed miserably,” Kibar says. “We call our platform a fountain of youth, but piece by piece.”

“After all is said and done, if we have just one approval, then we have failed miserably,” Kibar says. “We call our platform a fountain of youth, but piece by piece.”

The latest version is the wildly successful app, Pokémon GO. Since its launch in July of 2016, Pokémon GO has been downloaded more than half a billion times—and grossed more than $500 million dollars. For a little perspective, that’s over twice as much money as Ghostbusters II.

The latest version is the wildly successful app, Pokémon GO. Since its launch in July of 2016, Pokémon GO has been downloaded more than half a billion times—and grossed more than $500 million dollars. For a little perspective, that’s over twice as much money as Ghostbusters II.

A long, long time ago—way back when Facebook was young—Virginia and I discussed the possibility of becoming “friends” in that newfangled way.

A long, long time ago—way back when Facebook was young—Virginia and I discussed the possibility of becoming “friends” in that newfangled way.

“It was a good environment for people to do the wrong thing,” she says.

“It was a good environment for people to do the wrong thing,” she says.

To enter Los Angeles County from the southeast, follow Pacific Coast Highway through Seal Beach and onto a bridge spanning Los Cerritos Wetlands and the San Gabriel River. Off to your left, the marshy expanse turns to ocean. On your right, factory smokestacks stand against a hazy mountain range. The four-lane road narrows as it rises over the swamp. Go about a quarter mile until you reach a stoplight, where the road levels and widens again. You’re in Long Beach now. There’s a Whole Foods on the left if you’d like a snack.

To enter Los Angeles County from the southeast, follow Pacific Coast Highway through Seal Beach and onto a bridge spanning Los Cerritos Wetlands and the San Gabriel River. Off to your left, the marshy expanse turns to ocean. On your right, factory smokestacks stand against a hazy mountain range. The four-lane road narrows as it rises over the swamp. Go about a quarter mile until you reach a stoplight, where the road levels and widens again. You’re in Long Beach now. There’s a Whole Foods on the left if you’d like a snack.

In his New York Times bestseller Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic Future, Ashlee Vance ’00, veteran tech journalist and TV host of Bloomberg’s Hello World, reports on the daring business titan’s life and the rise of his innovative companies in finance, the auto industry, aerospace and energy. With exclusive, unprecedented access to Musk, his family and friends, Vance interviewed nearly 300 people for a book hailed as “masterful,” a “riveting portrait,” and “the definitive account of a man whom so far we’ve seen mostly through caricature.” Vance talked to PCM’s Sneha Abraham about the journey of the book and about Musk—a man both lauded and lambasted.

In his New York Times bestseller Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic Future, Ashlee Vance ’00, veteran tech journalist and TV host of Bloomberg’s Hello World, reports on the daring business titan’s life and the rise of his innovative companies in finance, the auto industry, aerospace and energy. With exclusive, unprecedented access to Musk, his family and friends, Vance interviewed nearly 300 people for a book hailed as “masterful,” a “riveting portrait,” and “the definitive account of a man whom so far we’ve seen mostly through caricature.” Vance talked to PCM’s Sneha Abraham about the journey of the book and about Musk—a man both lauded and lambasted.