PCM: You’ve said your first year at Pomona has been a year of listening. What have you heard, and are there some important things you’ve gleaned from it? Any big surprises?

PCM: You’ve said your first year at Pomona has been a year of listening. What have you heard, and are there some important things you’ve gleaned from it? Any big surprises?

Starr: Well, even though the College has changed a lot over the last 30, 40 or 50 years, there are some things about it that remain the same and should continue. And one of the things that I think is most remarkable is that every Sagehen I’ve met is defined by being intensely curious. There’s a kind of curiosity that is a fundamental characteristic of Pomona alumni and students and faculty, and there’s also a persistence to the relationships that people build. I’ve met with alumni five years out. I’ve met with alumni 50 years out. And for many of them, their core friendships, the ones that defined who they are, were forged here at the College. The fact that this has persisted is a really wonderful testament to what happens on this campus, and that is something that we have to continue to nurture.

Also, we’re an incredibly caring community. Most of us want to serve other people in some significant way in our lives. Whether this happens through teaching or building things or nurturing communities or health care, this is a group of people who really want to be there for others.

PCM: Strategic planning implies change, but Pomona is already one of the very best liberal arts colleges in the world. So the obvious question is: Why should we change? Or is the planning process really about something other than change?

Starr: Strategy does not mean simply change. I think a key part of the strategic planning process is setting priorities. Pomona has been really lucky to do everything we do so very well, but as we move into our next phase, we need to say: “We don’t have unlimited resources, and the question is: How are we going to use those resources best?” We’ve done some wonderful things at this college by prioritizing people. That’s been in financial aid; it’s been in resources for faculty; it’s been in benefits. And now it’s time for us to say: “Okay, where do we decide we’re going to make our next range of investments as a college?”

And while we are, I think, one of the best, if not the best, liberal arts college in the world, “best” is always contextual. And because the world changes around us, we don’t want to sit still. So we have to think about how we are helping to develop the best talent that is coming through our doors today and then the next five years and the next five years after that. So that, hopefully, is what planning is going to help us achieve.

PCM: The rapidity of change today has gotten quite daunting. What does that do to a planning process? How far ahead can we legitimately plan?

PCM: The rapidity of change today has gotten quite daunting. What does that do to a planning process? How far ahead can we legitimately plan?

Starr: I think five to seven years is a reasonable horizon, because one of the things that we do as a college is try to take the long view and not be reactive to everything that comes across the bow. Part of what’s supposed to happen in your time at a liberal arts college is for you to slow down and think, and so, even though change happens at a very rapid pace, we have to be thoughtful.

Still, you can rationally look out and say, “We know we have buildings that we need to think about. We know that we have an endowment that we have to take care of. We know that we’ve got a four-year horizon for just about every new student who comes in.” So some time scales are a given. But I think the time of a 10-year strategic plan has probably passed, because the economic conditions change too rapidly, and global conditions change too rapidly to think that far out.

PCM: Are there any past commitments that you think are untouchable because they’re so intrinsically a part of who we are?

Starr: I once had a student who did her dissertation on the idea of culture and the origins of that term—coming out of the earth. Culture builds up over time. Every seed that’s planted changes it—as does every wind that comes in, every person that walks through—but the culture still rebuilds.

The culture of Pomona that seems most self-perpetuating, and also best, is that sense of a contemplative, sharply focused, curious, residential, broad, liberal arts education. I don’t think we would ever want to change that, because the whole point of a liberal arts education is that it allows you to adapt to the world around you.

I think that our commitment to the diversity of human experience should not change because, again, what we are here to do as an educational institution is to make the fullness of human history, of human knowledge, continually available. And that needs to be available to as many of the most talented people as we can properly serve. So our commitment to diversity, I think, can only continue.

And ultimately, we have defined ourselves, in some ways, as an opportunity college, so being able to admit the best students regardless of their need is really important to our future.

PCM: Of course, the world around us continues to change. What external factors do you see out there going forward that may call for us to evolve?

Starr: I think national changes around immigration are certainly very concerning. Again, if we are committed to the actual human beings who make up the world, being able to welcome people from all corners of not only our own country but of countries from around the world is really important. For students and faculty, knowledge doesn’t sit happily within any one country or state, and we want that access to be there. So that’s certainly a very important consideration.

There are financial pressures, such as the tax on endowments, that mean that we will have to make some hard choices.

I think that there are certainly possibilities for us to focus on the human side of technology, and how it is that we ethically use the technologies that we create, and how we can design them inclusively, with an eye, as I said, to ethical use. We have lots of faculty members who are focused on that.

And then there are always the uncertainties that come with life. That, again, is the reason that we have a strategic planning process—so that we can take the time to say, “When that fork in the road comes, which of those paths are we going to walk?” So strategic planning is meant to help us manage those changes that we know about, but also externalities that will pop up on their own.

PCM: One of the things that continues to change is the nature of the students who are coming here. They’re all talented, but their experiences change. Their expectations in life change. What do you think we should be looking forward to in the next generation of Pomona students?

PCM: One of the things that continues to change is the nature of the students who are coming here. They’re all talented, but their experiences change. Their expectations in life change. What do you think we should be looking forward to in the next generation of Pomona students?

Starr: We know that there are massive demographic shifts going on in the U.S. and globally right now. There are going to be fewer and fewer college-age students, certainly in the Northeastern U.S. There’s going to be some growth in the West and in the South, but there’s going to be increased competition for the best students, and we want to continue to be able to draw the very best students that we can.

Many of us are concerned about the effects of lots of social media usage by this particular generation of high school and college students. There’s very good psychological evidence that social media can have a strong negative effect on adolescents. As they come into college, how do we build a community that can move beyond the digital to really focus on the face-to-face? That’s going to be a lot of work that we have to do.

It’s also true, as Beverly Tatum has pointed out, that this generation of students comes from schools that are much more segregated than any since pretty much Brown v. The Board of Education. And that means that when we talk about bringing a diverse group of students together, for many of them, if not most of them, this is the first time that they will be in close proximity to people very unlike themselves, and we are one of the most diverse communities in higher education today. So being intentional about how we bring people together is going to be a major challenge that we have to keep our eye on.

And I think it’s a wonderful challenge to have, frankly, because this is the world that we hope to create: a world where everybody can exist in a way that’s true to who they are and can work toward their own goals, but also the collective goals of what’s good for the world—clean water, good health care, functioning economies, strong schools. All of those things. Being one’s true self is not in conflict with being part of a caring community.

PCM: Years ago, I think many of us had the naïve notion that once you built up the diversity of the College it was mission accomplished. Of course, making a place truly inclusive isn’t quite that simple. Do you think we have a handle on that now?

Starr: Well, I think we’re close. I will say that something that I keep reminding myself is, you know, I’m an African-American woman who was not from a monied family and dealt with real prejudice growing up. And I was successful in a much less diverse environment than this, the one that I’m in right now, and so I have something of survivor’s bias, in that I was able to make it through despite all sorts of things that didn’t exist or were wrong. So I may have a predisposition to say, “Okay, well, you know, let’s get on with it.”

And I think many people who are successful—which would be just about all of our alumni and all of the people who are in power in the country—may have a kind of survivor’s bias. And it’s very difficult for us to imagine all those who didn’t make it and understand why. There could have been 20 like me, right?—40 like me, 50 like me—if things had been different or we’d had the same support. What would our world look like now?

So I think we need to really listen to our current students and try to understand how to broaden the path instead of thinking that the path that we were on was fine as it was.

PCM: Like most institutions of higher learning over the past year, Pomona has had some intense discussions about the nature and limits of free speech on campus. How do you think that is going to play into this planning process?

Starr: Well, I think that it will play into it on several levels. One is: We’re going to certainly think about our living communities and our learning communities and how we bring intentional dialogue into them. We already have one space that does this in a particular way, which is Oldenborg—where people come with the purpose of talking in a particular language—but how can we take that model of purposeful dialogue and expand it throughout our residential communities so that people can come in and speak intentionally with one another in an open and caring and critical and thoughtful way?

So as we think about residential programming, but also our facilities, how we bring people together is really important. A funny anecdote: When we were talking with students about plans for the new Oldenborg, we asked, “Well, do you want to have separate bathrooms or communal bathrooms?” Now, when I was in college, everybody wanted their own bathroom in a single. That seemed obvious. Why would you want anything different, right? But the students were saying, “No. Now, many of us live in these small rooms by ourselves, and the only place we have surprising, accidental conversations is on the way to the bathroom.” And that said something to me about the way in which we have provided so much individualized opportunity that people are yearning for the casual conversation. So how can we think about that?

We also need to think about what changes may be needed in our curriculum. This is a conversation that is deeply in the hands of the faculty as we think it through. How we structure discussions in our classrooms. What new tools we might need for students who may have learned to speak to one another over a screen rather than face-to-face.

PCM: On the subject of the curriculum, do you think the planning process will need to address the exploding interest in STEM fields and the imbalances that grow out of that?

PCM: On the subject of the curriculum, do you think the planning process will need to address the exploding interest in STEM fields and the imbalances that grow out of that?

Starr: Yes, that’s not going away any time soon. I think we’ve seen—not just here at Pomona but nationally—a large expansion in the need for computer science instruction, and that’s a need we have to meet. And in the allocation of resources and the need for new resources, we need to think about both the curriculum and how we deliver it.

One of the things that I think is very interesting about the way some of our faculty are thinking about technology is that technology is human. It’s not something that is outside of the liberal arts tradition at all. In fact, the liberal arts tradition—when we think about what liberal arts meant in their earliest incarnations—was about tools. Mental tools, physical tools and how to be creative in this new technological landscape—those are things that are going to be really important going forward.

We also have great things going on in the humanities, with Kevin Dettmar’s Humanities Studio, and in the social sciences, where people like Tahir Andrabi and Amanda Hollis-Brusky are thinking in dramatically new ways about old problems. Our athletics faculty are teaching amazing life skills, as well as nursing leadership and the whole student. We have a lot to be proud of.

PCM: There are a number of small private colleges today that are failing or having to make significant changes to keep their doors open. How does that affect Pomona and small colleges in general as we think about our future?

Starr: I actually think, nationally, the question’s not so much size. People talk about a crisis in small liberal arts colleges, and you can look at Antioch or Sweet Briar. Even Oberlin has had some financial challenges in the past few years. However, we just learned this summer that Northwestern, a large research-one university that’s highly endowed, is having financial challenges—slowing down on building projects and laying off staff, cutting budgets by as much as 10 percent in some divisions. So it’s not size that’s the question. It really has to do with how we think about our budgets and the priorities that we’re going to set and realizing that while we may have a list of 20 things we want to do, we can’t do them all at once. Staging our accomplishments is what’s crucial. And just keeping our eyes open, because a lot of problems don’t crop up overnight. The question is whether or not you are continually keeping your eye on where difficulties can arise.

PCM: I know Pomona is not immune to resource problems, though a lot of people probably think we are. Will the new strategic plan address the way we dedicate resources?

Starr: One thing that it’s really important for folks to understand is that 10 years ago, $19 million is what we spent on financial aid. Now we’re spending closer to $50 million. That money hasn’t emerged magically. The money comes primarily from the growth of our endowment. That endowment growth comes from investing, but it also comes from giving, and so when people ask, “Why should we give to Pomona?” it is because that’s an extra $30 million that goes to support every one of those promising students who are able to take advantage of this education. And we don’t only support our students with direct aid. The cost of a Pomona education is subsidized for every single student here by the generosity of past and current members of our community.

So one of my goals, personally, but also as part of strategic planning, is to come to a point where we have fully endowed all of our financial aid. So that we are not relying on tuition to help us bring the best students here. And ultimately we’re going to be calling on our community to help us to do that, and we will need every single dollar in order to achieve it.

We look at the students who are admitted and the students who applied, and we ask, “Are we losing people because we can’t give them enough aid?” We’re doing some of that analysis now to see how well we are doing at bringing students who we know would be successful here and helping them to stay, because part of the challenge is that family circumstances change. Parents may go through a divorce, have a health care crisis, an immigration challenge, and then suddenly what was full need only covers half of it or less. So it’s a problem I’m glad we have, but it’s still a challenge. How will we secure the purse strings to free the minds to thrive?

PCM: You’ve said you want everyone to feel free to put forward new ideas, big ideas. What are some of the criteria that you’ll be using to evaluate those new ideas?

Starr: I think the question is what benefit do they bring and to whom? We want to be able to say, “Are we getting the largest benefit that we can?” Even if it’s in one small area.

As a liberal arts college, we have to continue to prioritize our students. We are here to teach them. Faculty research, though, is a really important part of that because the curiosity that defines Pomona has to be fed, and research is one way that we feed that curiosity.

And we’re going to have to make decisions. For example, should every single person have a research opportunity in the summer, or should we think about research as a year-round experience? How do we think about prioritizing investments in health? How can we best serve the students who are here? If it means that we can’t, for example, have perfect, full-time medical care all year round, then maybe we need to have fewer people on campus in the summer.

There are going to be all sorts of trade-offs that we’re going to have to consider, but what we want is to know that we’re benefitting our students with every dollar that we spend. We want to know that we’re retaining and attracting the best faculty and staff, and we want to know that our students are going off to better themselves and to better the world. Those are the three things that are the ultimate criteria we have to judge anything by.

PCM: Pomona has never intentionally grown its enrollment, but as a practical matter, there has been slow, incremental growth over the decades. Should the College be more intentional about how it grows?

PCM: Pomona has never intentionally grown its enrollment, but as a practical matter, there has been slow, incremental growth over the decades. Should the College be more intentional about how it grows?

Starr: Absolutely. There are several important questions we should be asking. One is: If we think we’re doing this better than anybody else, is it morally acceptable to us to do it at this particular scale? And the question that I always want us to ask is: Who are we missing, and are we comfortable with that?

And there are different ways for thinking about this. Would we want to bring in more international students? Exchange programs for a year? That’s one way of thinking about who we might be missing. Would we want to have more robust exchange programs with other colleges as a way of thinking about who we’re missing? Historically, Pomona has grown by founding new colleges. That was the model that we took. We said, “No, we’re not just going to get bigger and bigger.”

We don’t seek to educate 10,000 people here. That’s not who we are. But what size would allow us to say, “We’re doing the most for the world in the best way we think we can?”

So we should talk about it. However, serving our students requires a ratio of students to faculty that is small, and I believe in that. So if we ever were to increase the size of our student body, the size of our faculty would have to increase too.

PCM: Are there obvious issues or opportunities that need to be addressed in the planning process? What excites or worries you going forward?

Starr: Yeah. I think some of the obvious things are in the physical plant—Rains, Oldenborg and Thatcher are buildings that need attention. We have been a very thoughtful institution in thinking about equity among the students and their experience. So if students in physics have access to great things, students in music should have access to great things. To me, that’s quite obvious.

We clearly need to think about financial aid, as I said, and we need to work with the other colleges around health and mental health, as well as preventing sexual violence—I think those are obvious. Asking questions about career outcomes and life outcomes—I think we’re definitely going to have to keep an eye on that too.

Beyond that, I’m really excited to see what comes up from the community as people start to think about what we want to be seven years from now. Ten or 11 years from now, looking back, what will we see as the defining experiences of the first-year students that come in between now and the end of the strategic plan? What will be different for them? What can we do to lay a foundation?

There’s the old phrase: You plant trees under which other people will sit. That’s what this is about. We are going to be planting trees for other people, and that is good gardening.

PCM: Ultimately, what is your best hope for both the strategic planning process and its outcome?

Starr: Ultimately, what I hope is that people enjoy engaging in a constructive, collective visioning of our future, because it’s about what we hope. It’s not about what we want, you know? What we want is about now. What we hope is about the future, and so hope is knowing you’re not going to get everything out of it, but still being enthusiastic and optimistic about the next steps that we’re going to take.

So that would be a big win if we come out of this feeling really hopeful about our future. Then it’s up to us to do the work.

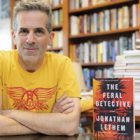

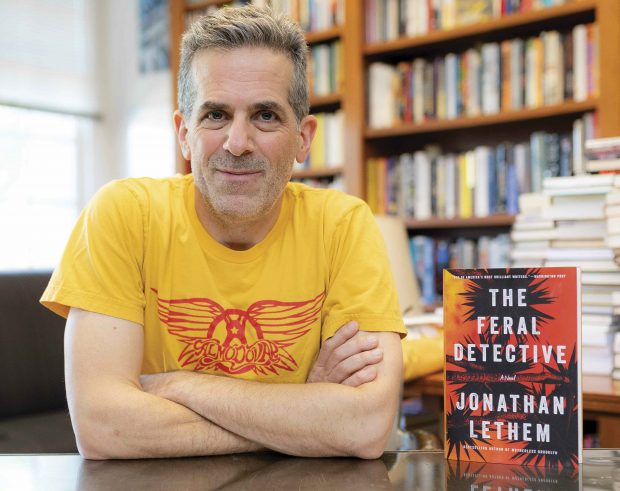

The motif of feral children was in critically acclaimed novelist Pomona College Professor Jonathan Lethem’s index of writing ideas for many years. There was the concept of urban feral children in New York City. Archetypal fictional characters like Tarzan and Mowgli. Real-life stories of feral children. A Pomona College course he designed on animals in literature had a portion devoted to the idea of the feral. All things feral fascinated him. So, a feral child of a different kind was born: the book The Feral Detective. This wild detective-book child was local-born, with the story set in the surrounding Inland Empire, the mountains and the desert region (what Lethem calls “the scruffier east”). He took the feral even farther, exploring desert-dwelling communes and creating two off-the-grid communes, the Rabbits and the Bears, that he writes about in his book.

The motif of feral children was in critically acclaimed novelist Pomona College Professor Jonathan Lethem’s index of writing ideas for many years. There was the concept of urban feral children in New York City. Archetypal fictional characters like Tarzan and Mowgli. Real-life stories of feral children. A Pomona College course he designed on animals in literature had a portion devoted to the idea of the feral. All things feral fascinated him. So, a feral child of a different kind was born: the book The Feral Detective. This wild detective-book child was local-born, with the story set in the surrounding Inland Empire, the mountains and the desert region (what Lethem calls “the scruffier east”). He took the feral even farther, exploring desert-dwelling communes and creating two off-the-grid communes, the Rabbits and the Bears, that he writes about in his book.

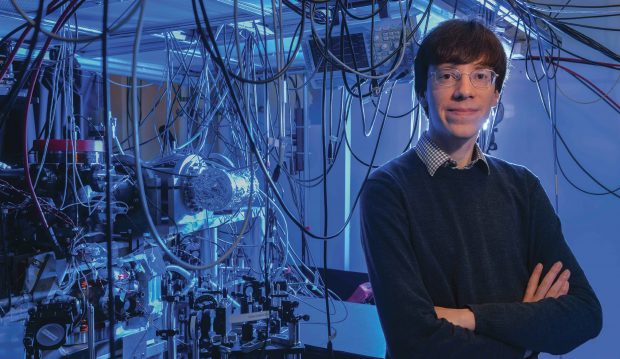

Grow up in Seattle, Washington, the son of two science professors, and get your first electricity set at the age of 5. Become fascinated with building little robots (including a mini Mars rover) with Lego Mindstorms from the age of 8 on.

Grow up in Seattle, Washington, the son of two science professors, and get your first electricity set at the age of 5. Become fascinated with building little robots (including a mini Mars rover) with Lego Mindstorms from the age of 8 on. Start playing the cello at age 10 and keep playing through middle school and high school. Do so in part for the same reason you’re attracted to research—because it allows you to work alongside others while pursuing long-term goals and building incremental skills.

Start playing the cello at age 10 and keep playing through middle school and high school. Do so in part for the same reason you’re attracted to research—because it allows you to work alongside others while pursuing long-term goals and building incremental skills. In middle school, attend a summer program on rockets and robotics, where you become intrigued by the mathematics of energy and momentum. Take a particular interest in air resistance and decide you want to do something about it for your next science project.

In middle school, attend a summer program on rockets and robotics, where you become intrigued by the mathematics of energy and momentum. Take a particular interest in air resistance and decide you want to do something about it for your next science project. Join the Frisbee team at school and become fascinated with the physics of flying disks. Teach yourself to use video tracking techniques in order to win the eighth-grade science fair with a project examining the aerodynamics of a spinning Frisbee.

Join the Frisbee team at school and become fascinated with the physics of flying disks. Teach yourself to use video tracking techniques in order to win the eighth-grade science fair with a project examining the aerodynamics of a spinning Frisbee. In high school, branch out into nonscientific disciplines with classes in philosophy, comparative government and politics. Realize you want to go to a college where you can do science while also exploring other interests.

In high school, branch out into nonscientific disciplines with classes in philosophy, comparative government and politics. Realize you want to go to a college where you can do science while also exploring other interests. Pick Pomona because it checks all your boxes, including a broad curriculum, strong programs in math and physics and the chance to do research. An opening for a cellist in the orchestra and appealing food options seal the deal.

Pick Pomona because it checks all your boxes, including a broad curriculum, strong programs in math and physics and the chance to do research. An opening for a cellist in the orchestra and appealing food options seal the deal. As a first-year, get your first taste of college physics in Whitaker’s Spacetime, Quanta and Entropy class. Get an invitation to work in Whitaker’s lab, in part because of your experience with video tracking and the aerodynamics of rotating bodies from your Frisbee project.

As a first-year, get your first taste of college physics in Whitaker’s Spacetime, Quanta and Entropy class. Get an invitation to work in Whitaker’s lab, in part because of your experience with video tracking and the aerodynamics of rotating bodies from your Frisbee project. After your first year, do a summer research project at the University of Maryland, College Park, in which you use computer code to track the location of sand grains in three dimensions. Bring that code back to Pomona to track flying, spinning seeds.

After your first year, do a summer research project at the University of Maryland, College Park, in which you use computer code to track the location of sand grains in three dimensions. Bring that code back to Pomona to track flying, spinning seeds. As part of Whitaker’s lab team, gather a lot of data during your sophomore year and spend your junior year analyzing it for a paper of which you’re listed as an author, published in the Journal of the Royal Society Interface. Expand upon this for your senior thesis.

As part of Whitaker’s lab team, gather a lot of data during your sophomore year and spend your junior year analyzing it for a paper of which you’re listed as an author, published in the Journal of the Royal Society Interface. Expand upon this for your senior thesis. Learn that you are one of three finalists in your category for the Apker Award. Give a nerve-wracking 30-minute presentation before the selection committee in Washington, D.C. Learn after starting at Stanford that you won.

Learn that you are one of three finalists in your category for the Apker Award. Give a nerve-wracking 30-minute presentation before the selection committee in Washington, D.C. Learn after starting at Stanford that you won.

For years I’ve wanted to publish a retrospective about Roger Revelle ’29, the oceanographer and climate scientist widely credited with pushing climate change into the consciousness of the nation and the world. So I’m delighted, finally, to include Ramin Skibba’s beautiful story about the scientist’s life and work in this issue. But as I edited the piece, I was troubled to learn that Revelle was also one of the very first targets of climate deniers—and remains a target to this day.

For years I’ve wanted to publish a retrospective about Roger Revelle ’29, the oceanographer and climate scientist widely credited with pushing climate change into the consciousness of the nation and the world. So I’m delighted, finally, to include Ramin Skibba’s beautiful story about the scientist’s life and work in this issue. But as I edited the piece, I was troubled to learn that Revelle was also one of the very first targets of climate deniers—and remains a target to this day.

Photos By Antoine Doyen

Photos By Antoine Doyen In his first blog post 11 summers ago, he celebrated the city’s parks and alleys and gardens. He responded emotionally to the sound of the great 19th-century organs in the churches of Saint-Sulpice and La Madeleine (“Tears of joy well in my eyes, taking me by surprise. My heart swells in my throat and explodes with the passion of the moment”). He reported briefly on visits to two jazz clubs. In one, a tiny bar (“about 4m by 8m, good beer, not so good sandwiches”), the audience barely outnumbered the performers: There were, in total, three listeners, including Crummer; the band was a tenor sax player and a pianist (“I listen to the sound of six hands clapping as they finish each tune”).

In his first blog post 11 summers ago, he celebrated the city’s parks and alleys and gardens. He responded emotionally to the sound of the great 19th-century organs in the churches of Saint-Sulpice and La Madeleine (“Tears of joy well in my eyes, taking me by surprise. My heart swells in my throat and explodes with the passion of the moment”). He reported briefly on visits to two jazz clubs. In one, a tiny bar (“about 4m by 8m, good beer, not so good sandwiches”), the audience barely outnumbered the performers: There were, in total, three listeners, including Crummer; the band was a tenor sax player and a pianist (“I listen to the sound of six hands clapping as they finish each tune”). During his first month in the city, at the coffee hour after a regular service at the interdenominational American Church in Paris, he noticed a woman across the room. “She looked like a damsel in distress,” he recalls. “I thought ‘Uh-oh, that’s trouble’ but I went over and introduced myself. This is a church for Americans mostly, but she was French. She had an apartment to rent on the Île Saint-Louis, and she was there to post a notice on the church bulletin board.”

During his first month in the city, at the coffee hour after a regular service at the interdenominational American Church in Paris, he noticed a woman across the room. “She looked like a damsel in distress,” he recalls. “I thought ‘Uh-oh, that’s trouble’ but I went over and introduced myself. This is a church for Americans mostly, but she was French. She had an apartment to rent on the Île Saint-Louis, and she was there to post a notice on the church bulletin board.”

Biochemist and UC Berkeley Professor Jennifer Doudna ’85 and her team discovered CRISPR-Cas9, a game-changing gene-editing technique with tremendous possibilities for curing diseases of all kinds, thanks to its precision. But with that finding, Doudna (who is also a Pomona trustee) discovered something else—that a great revelation sometimes brings with it a lot of wrestling. In A Crack in Creation, she tells a story that is about both success and struggle. PCM Book Editor Sneha Abraham talked to Doudna about the implications of what might be the most revolutionary scientific breakthrough of our time. This interview has been edited and condensed for space and clarity.

Biochemist and UC Berkeley Professor Jennifer Doudna ’85 and her team discovered CRISPR-Cas9, a game-changing gene-editing technique with tremendous possibilities for curing diseases of all kinds, thanks to its precision. But with that finding, Doudna (who is also a Pomona trustee) discovered something else—that a great revelation sometimes brings with it a lot of wrestling. In A Crack in Creation, she tells a story that is about both success and struggle. PCM Book Editor Sneha Abraham talked to Doudna about the implications of what might be the most revolutionary scientific breakthrough of our time. This interview has been edited and condensed for space and clarity.

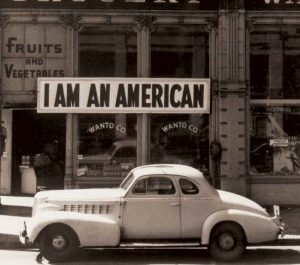

Of the many divisive cases in U.S. legal history, few are as haunting as Korematsu v. United States (1944). In the ruling, the Supreme Court and Chief Justice Hugo Black argued that national security took precedence over individual liberties. And they maintained the legality of the infamous Executive Order 9066—which ordered the incarceration of more than 120,000 Japanese-Americans during World War II.

Of the many divisive cases in U.S. legal history, few are as haunting as Korematsu v. United States (1944). In the ruling, the Supreme Court and Chief Justice Hugo Black argued that national security took precedence over individual liberties. And they maintained the legality of the infamous Executive Order 9066—which ordered the incarceration of more than 120,000 Japanese-Americans during World War II. The day after the attack on Pearl Harbor, the FBI conducted mass arrests of Japanese-American community leaders—sometimes in the middle of the night—and detained them in internment camps across the U.S. from Montana to Louisiana. Families often heard very little from their relatives in these camps, where their detainment lasted anywhere from a few months to several years. By 1943, the U.S. began a policy of deporting Japanese-Americans back to Japan as part of an exchange program with U.S. prisoners of war. On July 14, 1945, less than two months before the war’s end, President Harry Truman signed into effect a proclamation that permitted immigration officials to remove internees from the United States if they were deemed “a danger to the public peace.”

The day after the attack on Pearl Harbor, the FBI conducted mass arrests of Japanese-American community leaders—sometimes in the middle of the night—and detained them in internment camps across the U.S. from Montana to Louisiana. Families often heard very little from their relatives in these camps, where their detainment lasted anywhere from a few months to several years. By 1943, the U.S. began a policy of deporting Japanese-Americans back to Japan as part of an exchange program with U.S. prisoners of war. On July 14, 1945, less than two months before the war’s end, President Harry Truman signed into effect a proclamation that permitted immigration officials to remove internees from the United States if they were deemed “a danger to the public peace.”

PCM: You’ve said your first year at Pomona has been a year of listening. What have you heard, and are there some important things you’ve gleaned from it? Any big surprises?

PCM: You’ve said your first year at Pomona has been a year of listening. What have you heard, and are there some important things you’ve gleaned from it? Any big surprises? PCM: The rapidity of change today has gotten quite daunting. What does that do to a planning process? How far ahead can we legitimately plan?

PCM: The rapidity of change today has gotten quite daunting. What does that do to a planning process? How far ahead can we legitimately plan? PCM: One of the things that continues to change is the nature of the students who are coming here. They’re all talented, but their experiences change. Their expectations in life change. What do you think we should be looking forward to in the next generation of Pomona students?

PCM: One of the things that continues to change is the nature of the students who are coming here. They’re all talented, but their experiences change. Their expectations in life change. What do you think we should be looking forward to in the next generation of Pomona students? PCM: On the subject of the curriculum, do you think the planning process will need to address the exploding interest in STEM fields and the imbalances that grow out of that?

PCM: On the subject of the curriculum, do you think the planning process will need to address the exploding interest in STEM fields and the imbalances that grow out of that? PCM: Pomona has never intentionally grown its enrollment, but as a practical matter, there has been slow, incremental growth over the decades. Should the College be more intentional about how it grows?

PCM: Pomona has never intentionally grown its enrollment, but as a practical matter, there has been slow, incremental growth over the decades. Should the College be more intentional about how it grows?