Rick Hazlett

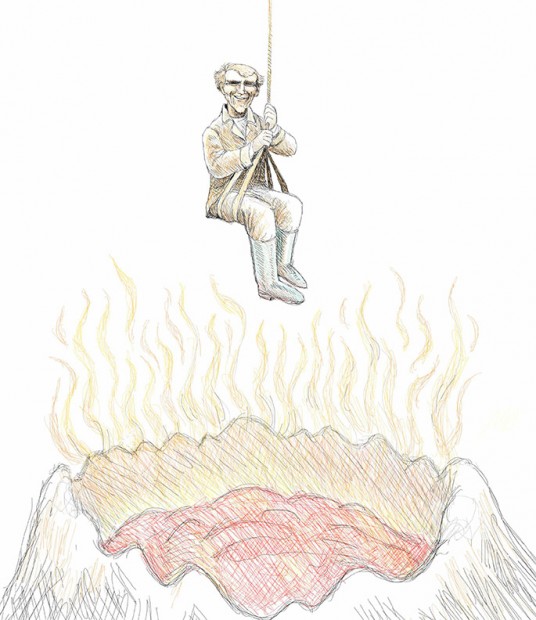

WHEN ASKED IF PCM could interview him about his retirement, Professor Rick Hazlett suggested that the writer would “have to rappel in to my interview, suspended over a pit of molten lava in a bat cave (or something like that!), where of course I’ll be doing research just for the ‘hell-uvit.’”

He was joking—sort of.

Hazlett is starting his retirement in style: He’s moving to Hawaii. A geology professor at Pomona since 1987, he’s trading Claremont for the Big Island, giving him a prime spot from which to pursue one of his greatest passions: volcano research. u

Hazlett calls the move a “bittersweet denouement” because of his deep affection for Pomona College and its students. But he has a long-running connection to Hawaii, having done many research projects there over the past 40 years, stretching back to the time he was a student.

“In a sense, I’m not really moving to a new landscape or an entirely new social circle,” he says. “It’s a bit of going home, in a way.”

A four-time winner of the Wig Distinguished Professor award, Hazlett chaired Pomona’s Geology Department for nine years. He helped establish the school’s Environmental Analysis Program and became its pioneer coordinator.

Hazlett is moving into a historic house in north Hilo, 30 miles away from the Hawaiian Volcano Observatory. His research will likely involve “looking at a prominent fault zone near the summit of the [Kilauea] volcano.”

“That sounds like work, but honest to God, it’s recreation for me,” he says with a laugh.

In addition, Hazlett will be working on two book projects. One is a new edition of a popular textbook, Volcanoes: Global Perspectives, that he co-wrote in 2010. He was also appointed senior editor for a research encyclopedia of environmental science, to be published by Oxford University Press. His focus will be the impact of agriculture on the environment.

“I’m really quite concerned about, and deeply committed to, solving environmental issues that I can impact. I figured this was a great way for me to pursue that mission while moving into retirement.”

Jud Emerick

AFTER TEACHING ART history at Pomona for 42 years, Jud Emerick says he still has as much interest in the field as ever.

“I’ll be doing art history for the foreseeable future,” Emerick writes in an email from Rome, where he’s spending the summer. The current focus of his research, he says, is “how architecture from early Christian and early medieval times in the Euro-Mediterranean world set stages for worship.”

Emerick’s areas of expertise are wide-ranging. As a professor, he taught courses on subjects such as prehistoric and ancient Mesopotamian, Egyptian, Green and Roman art; classical art in the Mediterranean; and painting in Italy during the 14th century.

Emerick and his wife have made Rome “a kind of second home” for the last 46 years. You can sense his passion for the place as he describes attending lectures at landmark sites, eating in local restaurants with friends, and talking art. After all these years, he says, he and his wife “still find that being in Rome is tantamount to being at the center of our art historical world.”

Emerick is also a music buff and says one of his greatest joys is his home music center. (His eclectic musical interests range from American blues to European chamber music to Seattle grunge.) In an age of digital recordings, the self-described audiophile says he hopes to do some online reviewing of new recording formats and equipment.

Honing his language skills is another goal. Emerick says he plans to “learn modern Italian verb tenses (how does one use the subjunctive?), get better at deciphering medieval Latin and even start the study of ancient/medieval Greek.”

Sidney J. Lemelle

AS SIDNEY LEMELLE heads into the future, he’s also revisiting his past. Specifically, Lemelle, a professor of history and black studies, is delving back into his 1986 Ph.D. thesis to expand it into a new manuscript.

His thesis chronicled the history of the gold-mining industry in colonial Tanzania, from 1890 to 1942. Now he’s exploring the post-colonial period, taking the subject up to the present. “I originally looked at gold, for the most part; now I’m looking at gold, diamonds and gemstones,” says Lemelle.

He adds that it’s difficult at times to re-examine his earlier work. “You’re going back to something you’ve written many years ago, and your ideas have changed since then. It takes a little humility.”

Lemelle joined Pomona’s faculty in 1986. A four-time winner of the Wig Distinguished Professor award, he chaired the Intercollegiate Department of Black Studies from 1996 to 1998 and the History Department from 2002 to 2004. His areas of expertise include Africa and the African Diaspora in North America, Latin America and the Caribbean.

Lemelle says he’s also looking forward to teaming up with his son, Salim Lemelle, a 2009 graduate of Pomona College, who is a screenwriter and writing intern at NBC/ Universal. The two plan to collaborate on screenplays.

“I hope we can write historical dramas and that sort of thing,” says the senior Lemelle. “We’ve been tossing ideas back and forth for a long time. Now I’ve got the time where I can actually do it. I’m excited about it, and so is he.”

Laura Mays Hoopes

LAURA MAYS HOOPES is writing a second act to her long career in science: She’s transitioning from biology professor to novelist.

In her retirement, Hoopes plans to put the finishing touches on a novel she penned while earning her MFA at San Diego State University in 2013. The book’s working title is The Secret Life of Fish, and it’s about a girl growing up in North Carolina who develops an interest in science and environmental issues.

“It’s not really autobiographical but it has certain things in common with my life, because I grew up in North Carolina, and I love the beauty of the state,” says Hoopes. “And I know a lot of strange stories about North Carolina history that I was able to weave in.”

Besides exploring the topic of women in science, she tackles issues of ethnicity and Native American identity in the book. There’s also a love story.

Hoopes came to Pomona College in 1993 and served as vice president for academic affairs and dean of the college until 1998, when she moved full time to the faculty. She taught both biology and molecular biology. In 2010 Hoopes wrote a memoir, Breaking Through the Spiral Ceiling: An American Woman Becomes a DNA Scientist.

Hoopes is also working on a nonfiction book. It’s a biography of two major female figures in science: Joan Steitz, a professor at the Yale School of Medicine, and Pomona graduate Jennifer Doudna ’85, a professor at the University of California, Berkeley.

“The two entered science about 20 years apart—Joan when there was a lot of discrimination against woman, and Jennifer when pretty much all the doors were open and everyone was just enchanted with her,” says Hoopes. “The whole idea is to look at key stages in their careers. It’s kind of a fun project.”

Ralph Bolton ’61

JUST AS HE DID 53 years ago in the Peace Corps, Ralph Bolton ’61 will be spending his post-Pomona years helping impoverished people in Peru.

The anthropology professor, who began teaching at Pomona in 1972, is president of the Chijnaya Foundation, which aids people in poor, rural communities in southern Peru. Created by Bolton in 2005, the organization designs and builds self-sustaining projects in health, education and economic development. Bolton does the work entirely on a volunteer basis.

“It’s extremely gratifying,” he says. “The people are very grateful. Many of these communities where we work are totally abandoned by any other nonprofit organizations or by the government agencies, and it’s one of the poorest areas of South America.”

His powerful connection to Peru first took root when he was a 22-year-old in the Peace Corps. In the small highland village of Chijnaya, he brought agrarian reform to the farming families, improving their lives dramatically. Hands-on service has always been part of Bolton’s approach as an applied anthropologist, whether he’s helping the destitute or advocating for HIV prevention.

His very popular Human Sexuality class at Pomona pioneered undergraduate discussions on AIDS and HIV when he began teaching it in the late 1980s. In 2010, he was honored with the Franz Boas Award for Exemplary Service to Anthropology, considered the most prestigious award in his profession.

Bolton says he’ll be spending about half the year in Peru, where he’s also working with fellow anthropologists and helping develop anthropology programs in universities.

“I can barely sign in to Facebook without having a Peruvian student or colleague begin to chat with me. So while I regret the loss of my Pomona students, the slack has certainly been taken up by other students of anthropology elsewhere who are very eager to continue to benefit from whatever I have to offer.”

James Likens

JAMES LIKENS SPENT 46 years teaching economics at Pomona. In his retirement, he’ll focus more on family than finance.

“I’m very big into family history. I have more than 17,000 names in my file,” he says. “Genealogy is fun for me perhaps because it’s so different from economics. Economics is driven by numbers and theory; genealogy is driven by documents and stories.”

Likens also served as president and CEO of the Western CUNA (Credit Union National Association) Management School, a three-year program spread over two weeks each July on the Pomona College campus. Since he joined the school in 1972, its annual enrollment has more than tripled from less than 100 to more than 300.

Likens, a winner of the Wig Distinguished Professor award, chaired Pomona’s Economics Department from 1998 to 2001. He also directed the yearlong celebration of Pomona’s Centennial. Likens has long been involved in community service—he has served on nonprofit boards and task forces—and says that will continue. “I will always be involved with service. I don’t know what it will be, but I will do something. It could be a board, or it could be a soup kitchen.”

He also plans to pursue his many interests, which include traveling, golfing, painting and spending time with his family, especially his four granddaughters. In addition, he’ll be working on a memoir.

“I have mixed feelings, of course, about retiring,” says Likens. “I have been at Pomona a long time, and it’s very much a part of my life. On the other hand, I now have the opportunity to do new things, and I look forward to that.”

“As the community changes, so does the language, and what isn’t preserved may be lost,” says Diercks.

“As the community changes, so does the language, and what isn’t preserved may be lost,” says Diercks. with individual people and then holed up analyzing the language, we don’t always get to see the whole community come together and celebrate research progress. It’s easy to focus on the academic side of things, but a celebration like this really drives home how intertwined language is with our identity, and how even small research advances matter so much to the community.”

with individual people and then holed up analyzing the language, we don’t always get to see the whole community come together and celebrate research progress. It’s easy to focus on the academic side of things, but a celebration like this really drives home how intertwined language is with our identity, and how even small research advances matter so much to the community.” In today’s session of Professor Valorie Thomas’s class on AfroFuturisms, the discussion focuses on

In today’s session of Professor Valorie Thomas’s class on AfroFuturisms, the discussion focuses on

Thai: Before 1985, most research in education fervently argued that schools help to equalize opportunities for students from low as well as high economic standings. Since then, there have been many debates about the problems of tracking in schools, including a study that was done in 1998 that set the tone for how we think about tracking today; that it tends to be a negative practice particularly for students who are not tracked at the upper end—immigrants, students of color, the poor.

Thai: Before 1985, most research in education fervently argued that schools help to equalize opportunities for students from low as well as high economic standings. Since then, there have been many debates about the problems of tracking in schools, including a study that was done in 1998 that set the tone for how we think about tracking today; that it tends to be a negative practice particularly for students who are not tracked at the upper end—immigrants, students of color, the poor.

Williams: I want to talk about Berg’s policy arguments, which are controversial. He says we should consolidate all federal food programs into one efficient entity, have a universal school breakfast, reward states to reduce hunger; allow nonprofits to compete for federal funds; give recipients more choice, provide additional services such as job training. What do you think?

Williams: I want to talk about Berg’s policy arguments, which are controversial. He says we should consolidate all federal food programs into one efficient entity, have a universal school breakfast, reward states to reduce hunger; allow nonprofits to compete for federal funds; give recipients more choice, provide additional services such as job training. What do you think? Next, a student-led discussion focuses on I’m Working on That: A Trek from Science Fiction to Science Fact by William Shatner and Chip Walter, and covers topics ranging from wearable computers and biowarfare to cryogenics and virtual reality.

Next, a student-led discussion focuses on I’m Working on That: A Trek from Science Fiction to Science Fact by William Shatner and Chip Walter, and covers topics ranging from wearable computers and biowarfare to cryogenics and virtual reality. Tanenbaum: How many people do you see wearing their earpieces 24 hours a day, seven days a week? I think we’re already there. I want to ask a question that gets at both virtual reality and the wearable computers.

Tanenbaum: How many people do you see wearing their earpieces 24 hours a day, seven days a week? I think we’re already there. I want to ask a question that gets at both virtual reality and the wearable computers. Students in Professor Tomás Summers Sandoval’s Latino Oral Histories class spent the fall semester interviewing Chicano Vietnam veterans as part of a project that will live on for posterity.

Students in Professor Tomás Summers Sandoval’s Latino Oral Histories class spent the fall semester interviewing Chicano Vietnam veterans as part of a project that will live on for posterity.