Teeny Tiny Immortals

Teeny Tiny Immortals

Biology: Professor Daniel Martinez

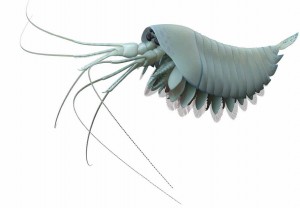

Providing the strongest evidence to date that some animals have the potential for immortality, new research released in December confirms the tiny hydra does not age and, if kept in ideal conditions, may just live forever.

In a co-authored paper published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) journal, Pomona College Biology Professor Daniel Martínez caps a decade of research into these centimeter-long freshwater polyps with a knack for longevity.

The paper titled “Constant mortality and fertility over age in Hydra” shows hydra could live in ideal conditions without showing any sign of senescence—the increase in mortality and decline in fertility with age after maturity, which was thought to be inevitable for all multicellular species.

Working with James W. Vaupel of the Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research (MPIDR) in Rostock, Germany, Martínez duplicated earlier findings regarding hydra immortality, but on a much larger scale. That scale, Martinez says, is key to the study’s significance, along with the fact that the hydra showed constant fertility over time, defying expectations for most organisms.

The latest study took 2,256 hydra from two closely related species and conducted experiments in two laboratories (at Pomona College and the MPIDR) over an eight-year period, doubling the amount of time from Martinez’s previous experiments showing hydra living for four years.

“I do believe that an individual hydra can live forever under the right circumstances,” says Martínez. “The chances of that happening are low because hydra are exposed to the normal dangers of the wild—predation, contamination, diseases. I started my original experiment wanting to prove that hydra could not have escaped aging. My own data has proven me wrong—twice.”

As one of the world’s leading scholars on hydra phylogeny and the evolution of aging, Martínez in 2010 received a $1.2 million grant from the National Institutes of Health for research on the mechanisms underlying lack of senescence in members of the genus Hydra. In 2013, he received a grant from The Immortality Project at UC Riverside to study the implications of hydra’s lifespan on medicine and increasing human longevity.

“Hydras are made of stem cells,” Martínez says. “Most of the hydra’s body is made of stem cells with very few fully differentiated cells. Stem cells have the ability to continually divide, and so a hydra’s body is being constantly renewed. The differentiated cells of the tentacles and the foot are constantly being pushed off the body and replaced with new cells migrating from the body column.”

The project was labor-intensive and, at times, tedious. Each hydra had to be individually fed three times a week. The man-made freshwater in which the hydra lived needed to be changed three times a week. “Many, many hours of work went into this experiment,” says Martínez. “I’m hoping this work helps sparks another scientist to take a deeper look at immortality, perhaps in some other organism that helps bring more light to the mysteries of aging.”

—Carla Guerrero

What’s in a Name?

What’s in a Name?

Economics: Professor Gary Smith

The study landed just in time for the 2014 hurricane season, and it created quite a weather system of its own.

A team of university researchers had found that female-named hurricanes are deadlier, and they posited that this was due to sexism—people didn’t take hurricanes with female names as seriously. They concluded that changing a severe hurricane’s name from Charley to Eloise “could nearly triple its death toll.”

The findings, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, drew international media attention. They also drew skepticism from some observers and academics who questioned the methodology.

Economics Professor Gary Smith digs more deeply into those doubts in his new paper, “Hurricane Names: A Bunch of Hot Air?,” published in Weather and Climate Extremes. In addition to questioning the methodology, Smith uses new data to provide the most extensive look at the controversial findings so far. Smith finds the hurricane names conclusion is “based in a questionable statistical analysis of a narrowly defined data set” and does not hold up when looking at a more inclusive set of data or at a fresh set of data.

His skepticism was heightened by the study’s conclusion that there is no female-male effect for less severe storms. If the sexism theory is true, he says, it ought to be most apparent for storms of questionable danger.

“It is implausible that an imperiled public’s response to a potential storm of the century—with catastrophic warnings broadcast by news media that feed on sensationalized reporting—depends on whether the name Sandy is perceived to be a feminine or masculine,” notes Smith.

Smith found that the original study’s conclusions depended on the inclusion of pre-1979 data, a period when all tropical storms were given female names. Hurricanes happened to have been stronger during these years and it is likely that infrastructure was weaker and there was less advance warning. It is more scientifically valid to analyze storms since 1979, when weather officials started assigning alternating female and male names before the hurricane season begins.

Smith also found that the statistical analysis was flawed and that the authors estimated at least a dozen models, which he calls a sure sign of tortured data. Smith tried to replicate the original research by 1) looking at a wider set of data and 2) looking at a fresh set of data.

The original study, Smith notes, excluded tropical storms that did not meet the wind-speed threshold to be labeled hurricanes, as well as storms that stayed off the coast and did not make landfall in the U.S. It also excluding deaths that occurred outside the U.S. When a wider set of data is considered, the study’s conclusions don’t hold up, says Smith.

For a second test, Smith looked at Pacific storms—the original research only considered Atlantic storms—and again found no difference in fatalities from female-named and male-named storms.

The Fletcher Jones Professor of Economics at Pomona, Smith teaches finance and statistics and pursues research on topics such as housing prices and stock prices. Author of Standard Deviations: Flawed Assumptions, Tortured Data, and Other Ways to Lie with Statistics, Smith also has a penchant for looking more deeply at implausible research findings, such as the report (published in the British Medical Journal) claiming that Japanese and Chinese Americans are susceptible to heart attacks on the fourth day of every month because in Japanese, Mandarin and Cantonese, the pronunciation of the words for “four” and “death” are very similar.

Smith laments that, “Statistical analyses are indispensable for evaluating competing claims and making good decisions. Unfortunately, the credibility of useful analyses is undermined by studies that torture data.”

—Mark Kendall

Supervolcanoes

Supervolcanoes

Geology: Professor Eric Grosfils

Almost 10 years ago, Geology Professor Eric Grosfils published a scientific paper on the stability and rupture of small magma reservoirs, challenging the current theory behind what triggers volcanic eruptions. One key finding was that magma buoyancy plays almost no role as a trigger. Grosfils’ research today continues to expand upon that work and influence the field of volcanology.

A new study published in the Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research, led by Patricia Gregg of the University of Illinois in collaboration with Grosfils and Shan da Silva from Oregon State University, shows that the same is true for the much larger systems that feed supereruptions.

The long-held idea is that the buoyancy in magma, which has lower density than the rock around it, begins to create pressure and push against the crust until it breaks, permitting magma to move upward and feed an eruption. These pressures, however, contribute in only minor ways relative to other factors. “Buoyancy doesn’t appear to be the trigger for such eruptions as others have argued,” says Grosfils, suggesting that previously identified factors, including external fracturing during roof collapse, remain the critical drivers for supervolcano eruptions. “We know that really big magma bodies accumulating at shallow levels in the crust can feed large explosive eruptions like the past climactic events at Yellowstone or Long Valley,” explains Grosfils. “All of us are interested in discovering what it takes for a system like that, just sitting there happily minding its own business, to begin erupting. What happens in the reservoir and surrounding crust that allows the materials to escape and feed a large, catastrophic volcanic eruption?”

“There are still many aspects to triggering supereruptions that we still do not understand. Our recent investigation helps to rule out one potential eruption triggering mechanism, buoyancy, but there is still a lot of additional work to be done to better constrain the mechanisms that trigger supervolcano eruption,” says Gregg.

Given the additional work left to figure out what sets off supervolcanoes, the opportunities for students to explore and learn are plentiful, and Grosfils’ collaborative nature and mentorship has already inspired some students to continue the work.

Recent Pomona graduate Robby Goldman ’15, is one of those students. He will be working with Gregg the following academic year pursuing volcano dynamic models on a large scale as a graduate student at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign’s geodynamics program.

A geology major at Pomona, Goldman worked with Grosfils and another geology student, Jack Albright ’16, on a project modeling magma chambers in three-dimensional space using the finite-element modeling software COMSOL Multiphysics. The goal of that research was to better understand how the formation of large, cauldron-shaped depressions known as calderas, are influenced by pressure changes in the underlying magma chambers. Their research was presented at the annual Lunar and Planetary Science Conference last spring in Houston.

Goldman is now headed to New Zealand on a Fulbright grant to continue his work in an ancient volcanic system, and he says his work with Professor Grosfils directly influenced his decision to apply for the Fulbright grant.

Adds Gregg, “Working with Professor Grosfils is incredibly enriching. His patience and generosity of time, acting as a critical sounding board as we work through the physics and dynamics of our volcano models, makes doing science together fun and exciting.”

—Carla Guerrero

“As the community changes, so does the language, and what isn’t preserved may be lost,” says Diercks.

“As the community changes, so does the language, and what isn’t preserved may be lost,” says Diercks. with individual people and then holed up analyzing the language, we don’t always get to see the whole community come together and celebrate research progress. It’s easy to focus on the academic side of things, but a celebration like this really drives home how intertwined language is with our identity, and how even small research advances matter so much to the community.”

with individual people and then holed up analyzing the language, we don’t always get to see the whole community come together and celebrate research progress. It’s easy to focus on the academic side of things, but a celebration like this really drives home how intertwined language is with our identity, and how even small research advances matter so much to the community.” In today’s session of Professor Valorie Thomas’s class on AfroFuturisms, the discussion focuses on

In today’s session of Professor Valorie Thomas’s class on AfroFuturisms, the discussion focuses on

Thai: Before 1985, most research in education fervently argued that schools help to equalize opportunities for students from low as well as high economic standings. Since then, there have been many debates about the problems of tracking in schools, including a study that was done in 1998 that set the tone for how we think about tracking today; that it tends to be a negative practice particularly for students who are not tracked at the upper end—immigrants, students of color, the poor.

Thai: Before 1985, most research in education fervently argued that schools help to equalize opportunities for students from low as well as high economic standings. Since then, there have been many debates about the problems of tracking in schools, including a study that was done in 1998 that set the tone for how we think about tracking today; that it tends to be a negative practice particularly for students who are not tracked at the upper end—immigrants, students of color, the poor.