DURING THE SPRING semester, as Pomona seniors made their way through their final classes and prepared to slip into their graduation gowns, most still had one big item left on their to-do lists: their senior thesis.

The senior thesis is a capstone project that may well be the longest paper students have ever written. Intimidating as the project may sound—it normally takes a full semester or, in some cases, an entire year to complete—the consensus among students is that it lies at the heart of Pomona’s liberal arts education, giving them an opportunity to connect knowledge from across disciplines and to delve into a specific topic in depth.

As a rising senior soon to embark on a similar journey and eager to know more, I interviewed seniors from a variety of majors to learn about their experiences and seek their advice. The 10 projects featured here—ranging from a novel about the politics of fairy tales to an ambitious endeavor to teach computers how to dance—offer just a taste of the diversity of inventive work students are producing in their final year at Pomona.

Cinderella and Its Politics

Bianca Kendall Cockrell ’17, politics major

After an angry fairy sends everyone in her castle into an enchanted sleep, Princess Alexis must go to America to retrieve the one item that will break the curse: an apple. She befriends Rumpelstiltskin and a vegetarian dragon and ends up in New York City, a place where democracy reigns supreme…

This may not sound much like a politics thesis, and indeed, Bianca Cockrell’s thesis is anything but conventional. Instead of writing a traditional academic paper, Cockrell wrote a novel about the politics of fairy tales, an idea that she got excited about when she took Professor Susan McWilliams’ Politics and Literature seminar in the spring of her junior year. Over the following summer, she continued her quest with a Summer Undergraduate Research Program (SURP) project titled “Once Upon a Regime,” for which she traveled around several European countries and visited fairy tale centers, museums and universities, where she sought insights from fairy tale scholars.

As part of her overall project, Cockrell also submitted two other papers—a political theory piece about revolutions and nation building in fairy tales, and a case-study analysis of modernism and the idea of America presented in early Disney princess films. She proudly calls her thesis “a three-pronged political-theory, creative-writing and historical-case study.”

Cockrell’s reasoning for using this unique format stemmed from a “practice what you preach” idea: “I wanted to see how using classic fairy tale characteristics like ambiguous characters and clichéd storylines contributes to the success of the story and the successful transmission of the ideas and values in the story.” Through this process, Cockrell was able to explore fascinating questions, such as whether Cinderella is a revolutionary, whether too much freedom is good or bad and the role of fairy tale as a democratic vehicle.

Uber, Lyft and the Environment

David Ari Wagner ’17, environmental analysis (EA) major

Uber and Lyft, the “unregulated taxis” that are putting traditional taxi companies out of business, are expanding quickly and changing the landscape of urban transportation. David Wagner’s thesis analyzes the environmental impacts of such companies, particularly in California, with respect to travel behavior, congestion and fuel efficiency. The literature on these topics is new, which Wagner says was one of the most challenging and exciting aspects of this project. His analysis suggests that in several major urban areas, fuel-efficient taxis are being replaced by less fuel-efficient Uber and Lyft vehicles.

Wagner selected the topic while interning at UC Davis’s Sustainable Transportation Energy Pathways program, which focuses on three revolutionary developments in transportation: shared, automated and electrified vehicles.” Like the EA major, Wagner’s project is interdisciplinary, utilizing economic, statistical and political analyses, all of which he believes are essential to an understanding of environmental issues. EA can be an emotional topic, he notes—which is why it is both hard and necessary to approach it rationally.

Wagner considers it a good idea to write a thesis as an extension of another project. He also suggests that students who are about to embark on this journey treat it as seriously as they would treat a job, eventually aiming to send the completed product to employers in hopes of making a real contribution.

Estimating the Unknown

Benjamin Yenji (Benji) Lu ’17, mathematics and philosophy major

Benji Lu is a math and philosophy double-major interested in going into law or doing data science and statistical research. For his thesis in mathematics, he developed a method of enhancing the predictive power of a commonly used machine-learning algorithm known as “random forests.” His research seeks to quantify the degree of confidence associated with random-forest predictions in order to make them more meaningful and actionable. To do so, he has been working to increase understanding of the statistical theory behind the algorithm itself.

Lu’s interest in integrating statistics with machine learning began his junior year, when he took a course on computational statistics with Professor Jo Hardin. His thesis grew out of a subsequent SURP project with Hardin, during which he also worked with an applied-mathematics research group at UCLA. Over the course of his SURP project, Lu met daily with Hardin, who encouraged him to write daily reports on what he had learned, what he had done and what he still did not understand. Once the academic year began, they met weekly to continue the project as his senior thesis.

Lu says he has enjoyed working with an expert in such a close setting and applying knowledge from his classes to research. For him, mathematical reasoning can be fun, creative and exciting, and it connects well with philosophy, the other half of his double major. Both subjects, he explains, involve rigorous, purely logical argumentation that can yield both elegant theory and practical results.

So You Think You Can Dance?

Huangjian (Sean) Zhu ’17, computer science (CS) major

Sean Zhu got the idea for his unique thesis a couple of years back while playing Dance Central, a game that scores the player’s dance moves using motion capture. A computer science major and a member of the Claremont Colleges Ballroom Dance Company, Zhu thought it would be cool to combine the two interests by teaching computers how to dance.

But how does a machine learn dance steps?

“The computer learns from past data,” Zhu explains. “In this case, the data would come from past dance movements.” Using Kinect, the same device that Dance Central employs, Zhu was able to generate and input dance-movement data to his program.

“Computer creativity is a rising field of research,” says Zhu. “We may tend to think that computers cannot be creative, as creativity is a capability that is typically thought to be exclusive to humans. This project challenged me to think about what creativity is and ways to approach this question.”

The Philosophy of Political Control

Matthew Daniel Dahl ’17, politics major

While studying in China during his junior year, Matt Dahl took a Classical Chinese class that exposed him to many original texts in the literary language of ancient China. That’s when the politics major, specializing in political theory, began to question the usual interpretation of the writings of China’s most famous philosopher.

While contemporary scholars assume that Confucius was most concerned with the cultivation of benevolence, Dahl challenges that conclusion through a close reading of the Analects. His thesis argues that the true message of the text concerns methods of political control and the maintenance of power. His contention is that Confucius supports rule by the so-called “gentlemen” not because they are benevolent but rather because they know how to be crafty in their speech. In fact, Dahl claims, “gentlemanliness” is not at all coincident with any of the traditional tenets of Confucian ethics.

Such a reading has been neglected, he suggests, because scholars have overlooked the possibility that Confucius wrote the Analects in the same esoteric manner that Plato wrote the Republic. By applying new interpretive procedures, Dahl believes he has revealed some of the original, radical political teachings that Confucius subtly sought to impart.

Exploring the Pilgrimage to the Holy Land

Ana Celia Núñez ’17, late antique medieval studies (LAMS) major

Ana Núñez’s yearlong thesis examines six early Latin Christian pilgrim itineraria—the ancient equivalent of road maps. Using sources in both English and Latin, Núñez w sought to understand the ways pilgrims experienced the Holy Land as a landscape of blurred temporal boundaries between the biblical past and the pilgrim’s own present.

She recalls that she first came across LAMS in her sophomore year of high school, when she was a prospective Pomona student and happened to attend Professor Ken Wolf’s Medieval Mediterranean class. Now, with her thesis completed and her Pomona diploma in hand, she is heading to the University of Cambridge for a master’s of philosophy in medieval history, after which she aims to return to the U.S. for a Ph.D. and a career in academia.

Núñez says she found the thesis experience memorable and rewarding, and she has one bit of advice for students yet to embark on the journey: “Trust yourself, and it will get done.”

The Screen, the Stage and Beyond

Jaya Jivika Rajani ’17, media studies and environmental analysis major

Napier Award recipient Jivika Rajani spent her senior year working on two nontraditional theses, each with a uniquely creative focus.

For her media studies thesis, she curated a multimedia experience dubbed MixBox, transforming a section of the Kallick Gallery at Pitzer College into a multimedia installation that guided participants through an interactive conversation with a stranger. The catch was that they were separated by an opaque curtain and would never see the person they had just gotten to know. Rajani then filmed debrief interviews in which her participants reflected upon the experience of making connections with strangers when they couldn’t rely on snap judgments based on appearance.

For her environmental analysis thesis, Rajani drew on her background in theatre to write a play rooted in identity politics and environmentalism. After reading other environmental plays and researching works written about the Indian diaspora, she developed her three main characters to represent different schools of environmental thought, from deep ecology to ecofeminism. As one of five winners of Pomona’s 10-Minute Play Festival, Rajani had an opportunity to direct and act in an extract of the play with some friends. She is also working on adapting her work for the screen.

Reflecting on the process, Rajani said that “juggling two theses at once was definitely hard, but I really enjoyed it because I was always working on something that I was genuinely passionate about and felt that I owned from start to finish. I also couldn’t have asked for better advisors—they’ve been very supportive of my plans to continue developing my work beyond Pomona, so I definitely see my projects as much more than just graduation requirements.”

Exploring the History of Labor and War

Jonathan Richard van Harmelen ’17, history and French major

Jonathan van Harmelen’s yearlong thesis on Japanese American history during World War II focuses on the relationship between labor and the war effort. His research began while he was interning at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, where he worked under Noriko Sanefuji on an exhibit titled “Righting a Wrong.” He has also worked with Professor Samuel Yamashita through a number of history seminars.

The project involved working with public historians, collecting oral histories of survivors, reviewing newspaper articles and statistics and making site visits. Though numerous historians have examined this subject, van Harmelen believes further understanding such forgotten narratives is now needed more than ever. He notes that “the subject of Japanese-American incarceration during World War II is one of the darkest chapters in United States history. While I am not Japanese-American, understanding this crucial subject is a step that all Americans should take, and is now very timely given our unstable political climate.”

For his semester-long French thesis, Van Harmelen focused on the Algerian War and memory as represented through Alain Resnais’ 1963 film Muriel.

An Environmental Perspective on Local Issues in Claremont

Frank Connor Lyles ’17, environmental analysis (EA) major

Frank Lyles, inspired by the thesis of a 2015 EA alumnus, focused on local climate change, groundwater and water-rights issues by reviewing planning documents in Claremont.

Lyles saw the thesis, accompanied by “lots of caffeine” and many a fun conversation, as an awesome educational opportunity and took an interdisciplinary approach, applying the skills he learned from his history, geology and statistics classes to complement his work in EA. He says he thoroughly enjoyed working with Professor Char Miller, who provides feedback on all EA majors’ papers, as well as with Professor W. Bowman Cutter from the Economics Department.

During his final semester at Pomona he took an econometrics class and decided to use what he was learning there to expand his thesis. Part of the challenge was tracking down relevant people and generating interest among stakeholders.

As a Pomona College Orientation Adventure (OA) leader, Lyles likes to think about how EA changes the way he views everything: He stops looking at mountains as just mountains and now understands them as dynamic things that are constantly changing.

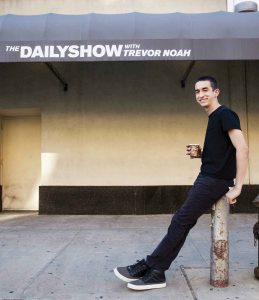

Law, Public Policy and Technology

Jesse Solomon Lieberfeld ’17, philosophy, politics and economics (PPE) major

Jesse Lieberfeld’s yearlong, in-depth investigation focuses on the relationship between the Fourth Amendment and modern communications, especially how laws that were developed long before the emergence of modern technology should be interpreted today and in the future. As a PPE major, Lieberfeld approached his research question from both legal and philosophical perspectives, poring over a range of U.S. Supreme Court opinions, articles on privacy, law review papers and interviews.

One of the challenges with this thesis project, says Lieberfeld, was that “there is a gap between studies that focus on law and public policy and those focused on technology; many are experts in one of these fields, but not all.” Lieberfeld’s thesis attempts to bridge this gap.

In particular, Lieberfeld says he enjoyed the interdisciplinary nature of this project and is grateful for The Claremont Colleges, since the politics and philosophy departments at each school have different specialties. He says he also appreciates the fact that Pomona does not have too many core requirements, allowing him to take a lot of niche classes.

April Xiaoyi Xu ’18 is a junior majoring in politics and minoring in Spanish.

Marisol Diaz ’18

Marisol Diaz ’18 Jacob Feord ’18

Jacob Feord ’18 Pablo Ordoñez ’18

Pablo Ordoñez ’18 Carly Grimes ’18

Carly Grimes ’18 Sylvia Gitonga ’20

Sylvia Gitonga ’20 Samuel Kelly ’18

Samuel Kelly ’18

PSYCHOLOGY: Assistant Professor Ajay Satpute

PSYCHOLOGY: Assistant Professor Ajay Satpute HISTORY AND CHICANA/0 LATINA/0 STUDIES: Associate Professor Tomás Summers Sandoval

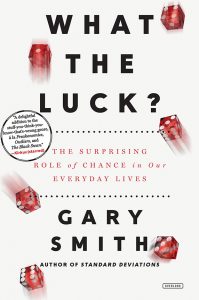

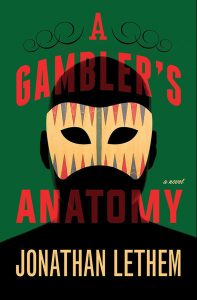

HISTORY AND CHICANA/0 LATINA/0 STUDIES: Associate Professor Tomás Summers Sandoval Professor Gary Smith Explains the Role of Chance in Everyday Life.

Professor Gary Smith Explains the Role of Chance in Everyday Life. Author/Professor Jonathan Lethem Discusses his Writing Process.

Author/Professor Jonathan Lethem Discusses his Writing Process. Professor Char Miller Looks Below the Surface of California’s Ecological History.

Professor Char Miller Looks Below the Surface of California’s Ecological History.

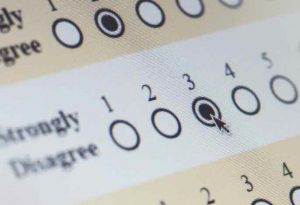

It’s not your typical online poll—the type you find on BuzzFeed to determine which Hogwarts house you’d be sorted into, or what your Game of Thrones name would be. Assistant Professor of Psychology Adam Pearson, along with Princeton social psychologist Sander van der Linden, have developed a series of online surveys for Time magazine to see what Americans think about issues like climate change, gun safety and genetically modified food and how in touch they are with others’ beliefs on these issues.

It’s not your typical online poll—the type you find on BuzzFeed to determine which Hogwarts house you’d be sorted into, or what your Game of Thrones name would be. Assistant Professor of Psychology Adam Pearson, along with Princeton social psychologist Sander van der Linden, have developed a series of online surveys for Time magazine to see what Americans think about issues like climate change, gun safety and genetically modified food and how in touch they are with others’ beliefs on these issues.

BIOLOGY: Assistant Professor of Biology Wallace Meyer

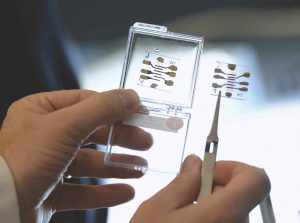

BIOLOGY: Assistant Professor of Biology Wallace Meyer CHEMISTRY: Professor Roberto Garza-López

CHEMISTRY: Professor Roberto Garza-López Each spring, juniors and seniors recognize outstanding Pomona professors by selecting the recipients of the Wig Distinguished Professor Award, the highest honor bestowed on faculty. This year’s recipients are (left to right in the image above):

Each spring, juniors and seniors recognize outstanding Pomona professors by selecting the recipients of the Wig Distinguished Professor Award, the highest honor bestowed on faculty. This year’s recipients are (left to right in the image above):